Doctoral dissertation has an important role to embark on an academic career confidently. The case is much more challenging for the early career doctorate who strives to contribute to the wider academic community. Using Swale's IMRD model, this study analyzed the rhetorical organization of English abstracts of 147 doctoral dissertations written between 2010 and 2015 in national graduate programs on English Language Teaching in Turkey. The results revealed 38 DAs with IMRD model and at least 22 rhetorically deficient DAs, lacking critical moves and linguistic realizations. Most DAs seem to exclude the conceptual framework, gap and important submoves. Omission of the Discussion move was also found to be a problem among the DAs. In addition, DAs from the half of the programs do not comply with the word limits offered by the official guidelines. Based on the results, a guideline was prepared to offer a remedy for the responsible bodies.

Over the last decades, there has been a burgeoning interest in analyzing and supporting academic writing of nonnative graduate students (Hyland &Tse, 2005; Ren & Li, 2011; Swales, 1990). Most of the concerning studies have so far focused on understanding the dispositions of producing texts in different academic genres (Hyland, 2004), specific linguistic aspects of academic writing (Swales, 1990), various contrastive rhetoric analyses (Samraj, 2005; Stotesbury, 2003) and ways to improve academic writing among graduate students (Storch & Tapper, 2009). However, few have reported on the rhetorical dynamics of the Doctoral Abstracts (DA) produced in the countries where English is a Foreign Language (EFL).

This area of inquiry merits further research and attention at least for three reasons. First, it is the doctoral dissertation that enables the novice researcher to step into a wider academic community, both locally and globally. Therefore, doctoral graduates should be informed about the critical role of the abstracts as well as how to produce effective ones for their dissertation and successive publications. Second, writing dispositions of nonnative graduate students in EFL contexts are mostly shaped within their monolingual culture (Kaplan, 1966), which in turn may result in various communication breakdowns within the international academic community. Third, an analysis of DAs written by non-native graduate students in an EFL context may help offer the right remedy before they begin to produce academic texts in different genres for the international arena. From this point of view, art of abstract writing is indeed an indispensable component of professional academic literacy.

The hope for doctoral dissertations to take the attention of the readership largely depends on a well-constructed abstract. Within the current zeitgeist of academia, hundreds of new research reports on a specific aspect of a discipline are published in different genres annually. Surely, the professionals who have to quickly choose what to read among this plethora of research naturally refer to the abstracts. In this respect, serving a gate-keeping function (Porush, 1995), the abstract is to be sufficient enough to summarize the complete study, convincing enough about its value, and comprehensive enough to express the author's stance. Therefore, the abstract as 'a part-genre of research articles' (Swales & Feak, 2009) or dissertations is considered as one of the most important genres in academic written discourse (Salager-Mayer, 1990, 1992; Staheli, 1986; Swales, 1990). They offer manageable bits of information within the constantly increasing information flow within the academia (Ventola, 1994). In other words, DA as a genre is the passport visa of the doctoral dissertation. Byoung-man and Ho-yoon, (2007) claim that even the achievement of the main research may be dependent upon the quality of the abstract.

Then how do doctoral students view and experience writing of a scholarly abstract? Kamler and Thomson (2004) accentuate that, writing effective abstracts should be viewed as an important aspect of doctoral supervision, and that academy neglects the art of writing abstracts. This case is also evident in these observations of novice nonnative doctorates of English Language Teaching (ELT) who are mostly frustrated with the difficulty of accessing academic domains, such as congresses, projects and Journals partly because they are inexperienced in producing effective abstracts. Similarly, Kamler and Thomson (2004) reported that early career researchers struggled to access academic domains and that they were surprised at how difficult most graduate students found writing abstracts. It is therefore important to shed light on practice of writing DAs in graduate programs of English language teaching in EFL contexts and to offer specific scholarly solutions.

In this article, the author analyzed the rhetorical organization of English abstracts of 147 doctoral dissertations written between 2010 and 2015 in all of the graduate programs on ELT in Turkey. The results made it necessary to prepare a guideline for abstract writing, not only for the field of ELT but also for all fields using the similar abstract genre in doctoral dissertations. To this end, the author prepared a brief guideline for writing abstract to be submitted to the responsible national body of the country, Council of Higher Education as well as to the graduate programs. Surely, raising awareness about art of abstract writing and proposing a guideline will help nonnative graduate students produce stronger abstracts for a better international scholarly communication.

After a brief discussion on its role and function, the major question might be that “What exactly is an abstract?”. Considering that this question in quotations yields 63,300 results on Google in June 2015, there needs to be a clarification about its definition. Hornby (1974)., in Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, defines abstract as “a short account, e.g. of the chief points of a piece of writing, a book, a speech, etc”. (p. 4). An academic writing center at University of Michigan (2015) notes that “An abstract is a short summary of your completed research. It is intended to describe your work without going into great detail. Abstracts should be self-contained and concise, explaining your work as briefly and clearly as possible” (p.1). A research-based account of an abstract provides a deeper insight about its nature: A study by Hyland (2009) on 800 Journal articles reveals that “The abstract, in fact, selectively sets out the writer's stall to highlight importance and draw the reader into the paper” (p. 70). Based on these statements, it appears that an abstract is a short rhetorically oriented text to convince the readership about its significance, production of which requires knowing what is novel, critical and appealing for the specific group of professional readers. Nevertheless, it might not be that easy for a doctoral candidate to draw the conceptual framework, indicate the gap and purpose, summarize the research design and choose the most important findings from a two hundred-page dissertation to present in a two hundred-word abstract.

The literature as well as the guidelines of preeminent Universities are abound with the types of abstracts and the ways to learn and use them. Abstracts are typically classified into four different types, which are informative, indicative, descriptive and critical (Byoung-man & Ho-yoon, 2007). The type of the abstract to adopt in a dissertation depends on the field. Generally, doctoral programs in foreign language teaching and neighboring fields prefer informative abstracts. An informative abstract provides readership with a glimpse of the whole research without a detailed reading of the main work. It basically includes the introduction, problem, hypothesis or research questions, method, result and conclusions (Porush, 1995). This basic structure of the informative abstracts enables the reader to have the glimpse of the major frame of the research study so that, they presumably do not have to read a specific chapter of the dissertation to find what they seek.

The studies on abstract analysis seem to focus on at least four different dimensions: analysis of move structures or macro-structures (Cross & Oppenheim, 2006; Santos, 1996, linguistic dynamics behind the moves or microstructures (Busch-Lauer, 1995; Pho, 2008), contrastive rhetoric studies (e.g., Byoung-man & Ho-yoon, 2007), and strategies for writing abstracts (Swales, 2004; Kamler & Thomson, 2004). Research on abstract genre may focus on both a specific discipline (e.g., Salager-Meyer, 1992; Santos, 1996; Lores, 2004) and different ones (e.g., Hyland, 2000; Samraj, 2005; Stotesbury, 2003; Pho, 2008). Viewing art of writing as a rhetorical negotiation process to gain access to the academic community, the author consider that a macro-structure (Van Dijk, 1980; Gardner & Holmes, 2009) analysis of DAs is of higher priority for the present context to offer some scholarly advice, as nonnative graduate students practice academic writing mostly within their monolingual culture.

Macro-structures of an abstract refer to the rhetorical organization that is conventionally accepted and utilized within a specific discourse community. The analysis process of the macro-structures is generally realized via major models developed over the last three decades. The most common models are IMRD (Swales, 1990) and CARS (Swales, 2004). IMRD (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) is largely referred to scrutinize how abstracts are rhetorically organized to comply with the conventions of the specific academic domains (Martin-Martin, 2003) . The CARS model, ‘Create A Research Space’, (Swales, 2004) basically concentrates on the global structures, or moves of the abstract. In light of the Swales' pioneering works, a great many studies examined rhetorical organizations and their linguistic realizations in research papers as well as in the abstracts of theses and dissertations. Those studies vary across languages and disciplines, such as Taylor and Chen (1991) in Physics and Educational Psychology, Arvay and Tanko (2004) in Linguistics, and Fakhri (2009) in Humanities and Social Sciences. Another model for abstract analysis was offered by Santos (1996), who revealed a prevalent model based on five moves with specific sub-moves, which are “situating the research, presenting the research, describing the method, summarizing the results, and discussing the results”.

This study fundamentally assumes that, abstract writing is a social practice requiring awareness about the expectations, norms and values of the target audience. Thus this social practice cannot be reduced to a narrow definition of the abstract as a 'short summary of the study'. Instead, art of abstract writing involves a socially driven rhetorical negotiation, a pursuit of presenting what is novel and innovative as well as the scholarly stance of the author. This negotiation or 'access-via-genre' process may be more challenging for the non-native doctorates in their early years, as Flowerdew (2001) points out the failure of non-native writers in developing an authorial voice. Within this frame, the present study examines rhetorical organization of the macro-structure moves in DAs and aims to answer following research questions:

In the field of English language teaching in Turkey:

All of the DAs were obtained from the internet site of the National Theses Database of the Council of Higher Education, which is the only responsible body to store and provide national theses in Turkey. According to the records of the National Theses Database, 147 doctoral dissertations were produced by all of the national graduate programs on ELT between 2010 and 2015. The initial investigations revealed that, 15 of those dissertations were heavily about either English linguistics or British/American literature with no reference or implication to foreign language teaching. Those dissertations were nevertheless included as they offer informative abstracts. A corpus of this size is thus sufficient to make tentative generalizations about the rhetorical structure preferences of early career doctoral graduates in this and the close areas. The results of the present study would attain an even higher degree of reliability when contrasted with other DAs from further research based on the same or larger selection of DAs in the neighboring disciplines.

The analysis of the data was carried out in three main stages. In the first phase, the author undertook the description of the rhetorical structure or macro structure of the abstracts by examining the overall textual organization of each abstract, referring to Dudley-Evans (1986), Salager- Meyer (1991) and Swales (1981,1990). It was assumed that, a rhetorical move in an abstract is a linguistic realization ranging from clauses to sentences and/or from phrases to words (Pho, 2008). Second, the abstracts were analyzed in terms of move structure, existence and place of certain moves by referring to IMRD framework (Swales, 1990) . Certain submoves were also identified for the IMRD framework throughout a data-driven process (Table 2). Those sub-moves emerged for Introduction Method and Discussion moves. The author coded specific submoves under Introduction as: “Purpose of the Study, Conceptual framework, Indicating Gap, Problem and Importance of the Study”. Byoung-man and Ho-yoon (2007) state that “Introduction is inclusive enough to involve a wide range of starters in communicative events, such as presenting problems or purposes” (p. 168) and confirms sub-moves identified for Introduction unit. Submoves for Method moves were identified as “Data collection” and “Data analysis”. For the Discussion, two submoves were coded: “Addressing the literature, Implications and Suggestions”. There existed further specific submoves for the Research move, but the research paradigms of the dissertations, qualitative, quantitative or various sorts of mixed method designs, did not let us reach consistent generalizations. These two steps of the procedures also contributed to reveal the possible limitations to be addressed in the proposed guideline. The complete analysis process was first carried out individually, and then the findings were compared to with an expert holding a PhD on genre analysis to attain inter-rater reliability. Total agreement throughout this process was reached after discussion. The names of the authors were kept anonymous when exemplifying moves from the DAs, and numbers were used to cite the dissertations.

In the third stage of Data Analysis, the author begun to construct the guideline for abstract writing to be used nationally by the graduate programs and Council of Higher Education. To this end, the available thesis guidelines of the graduate programs were reached online and analyzed how they guide graduate students to prepare their abstracts. There are currently 13 accredited graduate programs on ELT, but these investigations revealed 17 dissertations were supervised in 4 non-accredited programs. The analysis of the program guidelines was conducted merely on the accredited programs. Another important guideline published online by the Council of Higher Education gives the details of the submission process of thesis/dissertation to the National Theses Database. This document was also analyzed to see how abstract writing or preparation is guided. In addition, the author calculated the word count of each abstract and checked whether the instructions on abstract preparation of specific programs are applied in practice, and whether the programs or supervisors informally offer any structural or rhetorical instructions. Then, the guideline was prepared by referring to the current dynamics of the DAs specified within the present study and to the insights of the literature concerned. This process was also cross-checked with an expert throughout three discussion sessions.

This section presents and discusses the main results related to the research objectives. The first sub-section provides details about to what extent the guidelines of the graduate programs and the Council of Higher Education aid students to write abstract and how word count and limits are realized in the dissertations. The following three subsections are based on the research questions. Data findings on rhetorical organizations of the DAs are analyzed in terms of IMRD Model (Brett, 1994; Holmes, 1997; Stanley, 1984; Swales, 1990).

Among 13 accredited doctoral programs, 11 have a section in their guidelines explaining how to write an abstract of a doctoral dissertation. The word limits vary significantly: 6 programs offer 250 words for the abstract, 1 program offers 210 words, 2 programs limit abstract with 300 words, 1 program offers 400 words and another program limits the abstract with one page. Only 4 programs define the major moves of an abstract to some extent without getting into details. The rest 7 programs explain the page formatting issues. Based on the information provided in the guidelines of the graduate programs, the author found that graduate students are not fully informed about the art of abstract writing via those guidelines. It is beyond the limits of this paper to investigate to what extent the specific supervisors and dissertation committees guide the students in abstract writing process. Another important guideline analyzed is the thesis/dissertation submission guideline of the Council of Higher Education. In this document, no evidence of instructions about writing abstract is available.

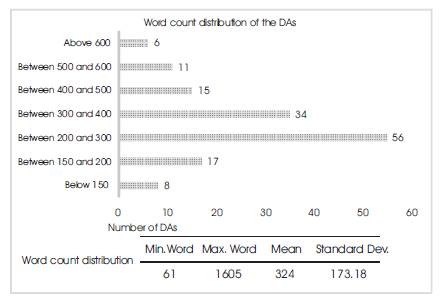

Word count analysis of the DAs in Figure 1 shows the distribution of words across 7 different ranges, from 'Below 150' to 'Above 600'. It was found that, 6 programs who offer some instructions about writing an abstract have a control over the number of words used in the DAs. Other 7 programs seem to be more flexible about the word count, as the distribution varies from 61 words to 1605 words (M= 324, SD= 173.18).

Figure 1. Analysis of Word Count Distribution of the 147 DAs

Evidently, most of the DAs in this context is limited between 200 and 400 words (f= 90, 61.2%) in a reasonable length. Although it is not offered by any of the programs, it appears that 25 DAs (17%) are below 200 words and 17 DAs (11.5%) are above 500 words, a total of which is 47 DAs (28.5%). Some of those abstracts can hardly be classified as an informative abstract genre because they are either too short or too long to accompany a doctoral dissertation.

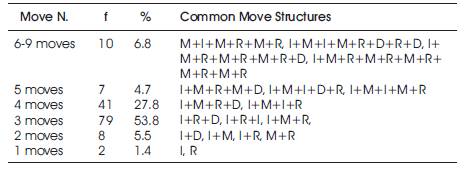

The analysis of the rhetorical structure of moves across the DAs (Table 1) revealed that, around half of all DAs utilize 3 moves (f=79, 53.8%), mostly Introduction, Research and Discussion moves (total f=44) although different variations exist, such as I+M+R (f=22) and I+R+I (f=13). The second popular move structure is the DAs with 4 moves (f= 41, 27.8%), which are I+M+R+D (f=38, 25.8%) and I+M+I+R (f=3). It seems that, DAs with 5 moves (f=7) are similar to the abstracts that follow IMRD model. Few were found to deviate from this model, such as I+M+I+M+R (f=2).

Table 1. Rhetorical Structure of the Doctoral Abstracts

The author identified 10 DAs with 1 or 2 moves, and 10 DAs with more than 6 moves and above, which make up the 13.7% of all DAs. Those DAs and some of the DAs with 3 moves were found to be rhetorically deficient and thus lacks communicative features and functions that an abstract is expected to possess. Much of the research in psychology as well as in discourse analysis (Carrell, Devine, & Eskey, 1988; Salager-Meyer, 1991) has revealed that, a deficient rhetorical organization of a text hampers the text comprehension, specifically for the nonnative readers of English. It is therefore commonly accepted that, a wellorganized abstract should follow the common rhetorical structures (Salager-Meyer, 1990, Swales, 1990, 2004) in a linear fashion to harmonize the moves coherently and reasonably.

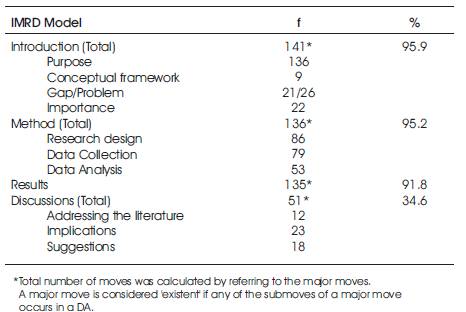

Following the analysis of the moves as complete units constructing the DAs, the author investigated the frequency of occurrence of each move and identified certain submoves in a data-driven approach (Table 2). This frequency analysis does not focus on where a specific move occurs in an abstract. Instead, it presents whether a given move occurs or not. It was found that, almost all of the Introduction moves include a purpose submove (f=141). However, only 9 DAs clearly define the conceptual framework. Also submoves on the gap addressed in the study and the problem of the research were found to be represented in 21 and 26 DAs successively. Another concern for the realization of the Introduction move is the limited number of submoves concerning the importance of the study (f=22). The frequency of occurrence of Introduction move confirms the study by Martin-Martin (2003), who compared research abstracts written in Spanish and English. However, a local study by Kafes (2012) revealed that, Turkish academic writers hardly employ Introduction units in research abstracts, which contradicts with the findings of the present research. The reason of this contradiction may stem from number and type of abstracts, as Kafes (2012) analyzed the abstracts of research articles.

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence and Distribution of Moves in the DAs

Method moves or units within the DAs were found in 136 dissertations, in which 86 DAs include submoves on research design, 79 DAs on data collection and 53 DAs on data analysis. Moves on research design refer to major aspects of the procedures. The reason behind the limited submoves on data collection and analysis is that around half of DAs do not indicate data collection tools and similarly only 53 DAs provide persuasive and abundant amount of information about validity/reliability (where applies) and statistical or qualitative analysis methods. However, whether persuasive and informative or not, most DAs include method moves in various rhetorical structures, which is in line with Santos's (1996) and Pho's (2008) findings.

It appeared the most omitted move is the Discussion move. The author spotted 51 DAs including a variation of a Discussion move, and among them 12 DAs address the literature to situate and/or interpret their findings. In addition, successively 23 and 18 DAs were found to have implication and suggestion submoves. The scarcity of the implication submoves is understandable in that dissertations might not be able to offer practical solutions based on their findings. However, a typical doctoral dissertation should explain what should be done as a continuum of its findings and indicate a gap in the concerning literature. These findings confirm the study by Ju (2004), who found that Chinese nonnative authors of English tend to omit the discussion move from the abstracts.

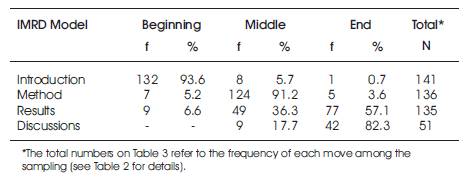

The author also attempted to analyze the occurrence order of the moves (Table 3) broadly and revealed that, the rhetorical structure of the DAs is fairly distributed when compared to IMRD framework. Nevertheless, few abstracts possess deficient structures in terms of order of the moves. Certain unexpected occurrence orders in the DAs, such as 8 Introduction moves in the middle and 1 move in the end of the abstracts may stem from how authors validate importance and problem of the study. This analysis showed that, at least 22 DAs have highly deficient rhetorical structure, as 9 DAs have a type of Results moves and 7 Method moves in the beginning, 8 Introduction moves in the middle, 5 Method moves and 1 Introduction move in the end of the DAs.

Table 3. Order of the Moves within the Das

It is worth noting that, the order of the moves in an abstract, as a unique genre, may not always give objective evidence about the rhetorical quality, as the author has a very limited linguistic environment to realize many communicative functions, such as summarizing, convincing and so forth. However, the author aimed to underline solely the extreme conditions in this analysis with an overall comparison of the DAs with IMRD Model, such as the appropriacy of a Results move in the beginning of an abstract. In this sense, the move order in the DAs in terms of IMRD model revealed 22 (14.9%) highly deficient DAs.

Around 75% of the DAs begin with the purpose statement using various versions of the purpose move “The aim of this study”, such as “It is aimed in this study”, “This study aims to/at” “The purpose of this study” and alike. Few dissertations draw the conceptual framework and indicate a gap or the problem in the first sentence, then link it to the purpose move, such as:

“Teacher education has been subjected to a number of research studies over the last thirty years and yet we are still trying to understand why people are attracted into teaching” (3rd DA).

“English is the main medium of communication among academic researchers. Publishing in international Journals may become very challenging for non-native speakers who may have different conventions of writing research articles” (9th DA) .

Few method moves are linked to the introduction moves by using cohesive devices like “For the purposes of the study”, “To this end” and “For this end”. The authors who used an Introduction move do not seem to use a transition device which may contribute to the coherence, thus the readability of the DAs. In addition, no common beginning moves were observed for the Method moves: some DAs elaborate immediately about research techniques, some others about the scope and sampling or about overall procedures. Nine DAs either embed a Method move (f=7) within the first Introduction move (31st and) or explicitly use a Method move (35th DA) at the very beginning of the abstract

“This mixed method study described the language learning beliefs and self-efficacy perceptions of firstst year” (31st Move)

“The current study is composed of two main parts as descriptive and experimental. The aims are, first to determine” (35th DA).

Results moves generally begin with the clauses like “The analyses showed that”, “The results revealed that” and “It was found that”. Among these, “The results indicate(d)/ show(ed)/demonstrate(ed)/reveal(ed) that” was found to be the most common versions. However, a few DAs begin to present the results without any explicit linguistic realization, such as:

“At the beginning of the study, performance of the participants in both groups did not show any statistically significant difference” (37th DA).

“As a result of t-tests comparing the mean durations of pausing preceding and following the conjunctions, it was detected that…” (42nd DA)

Discussion moves are not abound in the DAs (f=51). Those with Discussion moves either address the literature by citing specific studies (25th DA and 105th DA), gives suggestions based on the findings (30th DA) and explain the implications of the study (85th DA). In addition, a few generic submoves, such as “Suggestions were made”, “Implications were drawn” and “Implications were provided” were found within the Discussion moves.

“This finding is consistent with the predictions of the both gap-based accounts (e.g. the Active Filler Hypothesis (AFS) of Frazier, 1989) and gapless accounts …” (25th DA).

“This latter result is inconsistent with the renowned linguistic relativity hypothesis (Whorf, 1956) …” (105th DA).

“…it has suggested a remedial teaching activity consisting of two different ways that could help correct the mistakes in the use of these prepositions” (89th DA).

“The results have implications for improving language teaching, teacher training programs and materials” (85th DA).

Turkey is a part of the Bologna Process and has structurally defined the all levels of tertiary education accordingly (CoHE, 2015). In this respect, the standardization in scholarly products is as equally important as the standardization in each academic degree. It is no doubt that a standardized doctoral abstract genre will contribute to the dissemination of doctoral research. The findings of the present research showed that, the analyzed DAs vary significantly in terms of word count, length, rhetorical structure and linguistic mechanics behind those structures. Therefore, the guideline for abstract writing is included within this study.

The proposed guideline was prepared in two phases, and presented in a table format in Table 4. Initially, a literature review (Cross & Oppenheim, 2006; Kamler & Thomson, 2004; Lorés, 2004; Santos, 1996; Storch & Tapper, 2009; Swales, 1990, 2004; Swales & Feak, 2009) was conducted to find what the current scholarly insights highlight. Then, the guidelines of universities were analyzed to learn what preeminent universities offer to develop art of abstract writing for graduate students. This process was also refined by the findings of the present study, which shed light on the possible deficiencies in the rhetorical structure of the DAs.

A guideline should offer further instructions to realize the task of effective abstract writing (Table 5). To this end, a short list of steps was prepared to be referred when writing an abstract for a dissertation, and possibly for other research papers. A total of 14 suggestions are divided into two groups: rhetorical and linguistic. This list of instructions is mostly based on the guidelines of the Universities and the discussions with the colleagues, who supervise PhD students.

The results of the present study showed that, while 38 (25.8%) DAs written in the field of English language teaching followed IMRD model successfully, at least 22 (14.9%) were highly deficient in terms of rhetorical structure. In addition, the common dispositions were that, most DAs exclude drawing the conceptual framework, gap in the literature and/or practice as well as importance of the study from the Introduction moves. Omission of the Discussion moves was also found to be a problem across the DAs. With regard to the guidelines of the graduate programs on dissertation preparation, few seem to instruct for effective abstract writing. Other side of the coin is that, 47 DAs (28.5%) did not strictly comply with the word limits imposed by the official guidelines.

This portrait has resulted in the preparation of a guideline for abstract writing for graduate programs and Council of Higher education. The guideline is based on IMRD model (Swales, 1981, 1990) and provides instructions for writing effective abstracts. A suggestion list for rhetorical and linguistic strategies was also included to strengthen the possible pedagogic influence of the guideline. As the graduate programs analyzed within this study offer significantly different word-limits and abstract lengths, the guideline does not touch upon this issue.

Abstracts fulfill the public-relations function: they do tell the research to sell it (Yakhontova (2002) for the difference between 'telling' and 'selling'). This need for selling the research, according to Hyland (2000), stems from the competitive nature of the research community. Dissertations, surely part of this competitive market, are perhaps the most important research study of early career doctorates in that, it enables or disables the very first scholarly step into the academia. In this respect, the abstract of a dissertation and the competencies of the novice doctorate on art of abstract writing count for the graduate programs and for all other shareholders, including congresses, Journals, grant bodies and alike. The present study, within this frame, shed light on the current practice of a dynamic and a popular field of inquiry in Turkey, English language teaching. The results may be further refined by future research focusing on DAs with a contrastive rhetoric perspective, in which rhetorical and linguistic structures of the DAs are compared with the ones written by native speakers. Such a study would reveal how the monolingual context shapes writing dispositions of Turkish academicians and what further steps should be taken to strengthen the voice and ambitious research of the local doctorates.

The author would like to express his sincere thanks to Res. Assistant Betül Kınık of Gazi University for her enormous support and assistance at every stage of this paper.