Since its inception, Jordan has experienced large-scale and diverse immigration waves from neighboring countries. The research focuses on the wave that took place during and after the Gulf War of 1991, which left a lasting impact on the country's economy, social fabric, and in particular on the IT industry. The research used a field survey of 37 local companies as well as the analysis and synthesis of various data, and relevant government laws and regulations to probe the impact of that wave. It concluded that, the immigrants caused a boom in all sectors of the economy, as evidenced by the phenomenal 16% growth in the economy in 1992. They created new businesses and competition in the IT industry, and brought technical skills and managerial expertise, that gave a boost to the IT sector and forced the acceleration of local market concepts such as consulting, specialization, and marketing. The Jordanian Government played a passive role at best through its laws, regulations, and practices. During the following decade, few Jordanian IT companies reaped the benefits of the revamped IT sector and attained international fame, when for example, Maktoob portal was acquired by Yahoo. It is hopeful that other countries can benefit from the Jordanian experience in dealing with the ongoing immigration waves and the diversity they bring with them.

Since its inception, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has experienced large-scale immigration waves from neighboring countries, of which the most recent has been from Syria. There had been large waves of Palestinian refugees that Jordan had absorbed in 1948 and 1967. All these waves have brought with them diverse groups of immigrants into the country. The research here focuses on one of those waves, namely, the one that took place during and after the Gulf War of 1991. This particular wave left its lasting footprint on the country's economy, social fabric, and particularly on its information technology industry.

During and after the Gulf War of 1991, Jordan has experienced a major influx of about 3,60,000 people (which then constituted over 10% of the country's population) from Kuwait, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf States, of whom about 3,00,000 remained in Jordan. (About 30,000 - 40,000 who held valid Israeli-issued documents traveled to the West Bank, while the remainder moved on to Canada, Australia and other countries outside the region). The majority of the people arriving in 1991 already possessed Jordanian travel documents (U.S. Committee for Refugees, 1998). It is also estimated that, Jordan experienced a substantial capital inflow of (US$ 2- 3 billion), as a result of this, there was major influx of people into the country (Jordan Private Sector Assessment, 1995).

The world today watches the ordeal of the refugees from the Middle East to Europe, who bring with them hopes and aspirations of a new life for themselves, their families, and their host countries. What lessons can other countries learn from the Jordanian experience in dealing with immigrants, and how can they leverage the diversity of the new comers?

The purpose of the research is to address two issues. The first is, whether the returnees (immigrants) had any impact on the Jordanian economy, in general, and on the IT industry in specific. The second issue is, whether the Jordanian Government played any role in stimulating or hindering the growth of the sector through its laws, regulations, and practices during the 1990s. Five hypotheses are tested and conclusions are reached using a field survey of 37 local companies, synthesis of economic data, and analysis of relevant government laws and regulations.

Survey tools including questionnaire and interviews were conducted to obtain some key data. Surveys were collected from 37 IT companies in Jordan plus the IT trade association then, from the Jordan Computer Society (1999). Only companies in the capital city of Amman were chosen for the survey sample, since the capital city was inhabited by more than one-fourth of the population of the Kingdom.

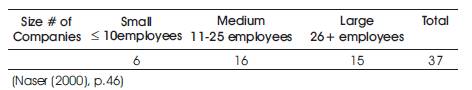

The surveyed companies included sectors present in the Jordanian market such as software development, hardware vendors, including local assembly, networking, Internet service providers, consulting and training, incubators, and systems integration (Jordan’s National Information Centre and UNDP, 1997). These companies were classified into three categories according to the number of employees. Table 1 shows the breakdown of surveyed companies, according to size.

Table 1. Sample according to Company Size

There was also an examination of the different laws and regulations that were in effect during the 1990s dealing with investments, telecommunications, intellectual property rights, and taxation including tariffs and customs duties.

Jordan, like many Less Developed Countries (LDCs), has limited natural resources, and it is economically dependent on foreign aid (Khasawneh, 1992). Kuwait used to absorb about 30% of Jordan's agricultural exports. Remittances from Jordanians and Palestinians living in Kuwait came to a halt. According to one estimate, 70% of Jordan's industrial capability was produced for Iraq. Transit trade with Iraq stopped as a result of UN sanctions. Tourist and transport industries suffered heavily as well. It is believed that, all these circumstances cost Jordan up to US $3 billion and an increase in unemployment from 20 - 40%. Saudi Arabia ceased oil shipments to Jordan, and many of Jordan's goods were no longer allowed to be sold in Saudi Arabia. The situation was further aggravated when hundreds of thousands of third-country refugees fled Kuwait via Jordan. Apart from the immediate economic hardship on Jordan, not all the effects have been negative. The Iraq-Kuwait crisis had helped strengthen the democratic process; conferences, rallies, and demonstrations were held around the country with few incidents, especially since the elections of November 1989 (Bennis & Moushabeck, 1991).

The major immigration influx that Jordan experienced during the Gulf War of 1991 was from people who were expelled from the Arabian Gulf states, mainly from Kuwait. As Table 2 shows, out of over 24,000 surveyed returnees, about 84% of them came from Kuwait.

Table 2. Distribution of Surveyed Jordanian Returnees' Households from August 10, 1991, to December 31, 1992, by Country of Residence and Years of Stay Abroad

According to El-Uteibi (1994), (p. 2), “the majority of the Jordanian returnees were of Palestinian origin who had never lived in Jordan before”. This immigration impacted the country's social, environmental, political, and economic affairs. El-Uteibi (1994), also estimates that some 10,000-15,000 educated and qualified Jordanian IT expatriates were repatriated into Jordan as a result of the Gulf Crisis, but the majority of them left the country.

Out of a random sample of 27 returnees who was interviewed in Amman, about why they chose Jordan for relocation, unanimous responses indicated that, they all held Jordanian passports or had some relationship with Jordan, whether it is through owning a house or having some relatives. The majority of the returnees were Jordanian expatriates who had never lived in Jordan before since the majority were Palestinians who left their homes after the 1967 war and were given Jordanian passports or citizenship (Bennis & Moushabeck, 1991).

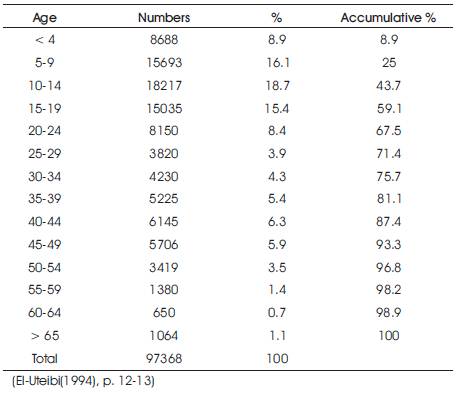

According to a survey carried out by Jordan's Department of Statistics between August 10, 1991, and December 31, 1992, the majority of returnees were under 45 years old, approximately 68% were below 25 years old (Jordan's Department of Statistics, 1993).Another survey was carried out by the National Center for Educational Research and Development during April 1991. Table 3, from this survey, shows the distribution of returnees by age.

Table 3. Distribution of Returnees by Age

About 48% of the returnees were females, while about 52% were males. The statistics indicated that, 68% of the economically active returnees were males (El-Uteibi (1994), p.15).

Males seemed to have better job opportunities than females for various reasons. The survey had indicated that 30% of the returnees were professionals while 53% of them worked at the Kuwaiti government sector. IT professionals are in the specialists and technical category. Also, 83% of those surveyed were males. Table 4 shows distribution, by occupation, sector, and sex.

Table 4. The Distribution of Jordanian Returnees from Aug. 10, 1991, to Dec. 31, 1992, of (15+) Years of Age who were working in Kuwait, by Sector of Employment, Sex, and Occupation

Table 4 also shows that about 53% of returnees surveyed worked for the Kuwaiti government while 47% worked in the private sector. Table 5 shows the breakdown according to years of experience, sex, and occupation.

Table 5. The Distribution of Jordanian Returnees from Aug. 10, 1991, to Dec. 31, 1992, of (15+) Years of Age who were working Abroad by Years of Experience, Sex, and Occupation

It is noted from Table 5 that, 44% of the returnees spent less than ten years abroad, while only 4% spent 35 years or more abroad, which may lead one to believe there was a good percentage of younger people in that surveyed sample.

What was also so special about the Jordanian returnees compared to other nationalities in Kuwait? According to El-Uteibi (1994), p. 25, the answer may be summarized in the following points:

The impact of immigrants on the Jordanian economy will be tracked as measured by the change in Population, Number of Registered companies, Workers' Remittances, Labor Force, Government Employment, Stock Market, Government Finance, and Social Impact.

Table 6 shows the growth of population in Jordan from 1989 to the year 1997.

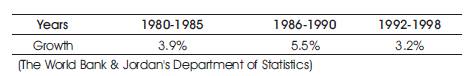

As Table 6 shows, Jordan's population in 1990 was 3.17 million, and when the next population census was conducted in 1994, the population was about 4.1 million. There was over 10% growth in the population of Jordan in a span of one year as a result of the return of 3,50,000 expatriates following the Gulf War. While having a look at the percentage of the growth of the population as shown in Table 7, it is seen that the country had an average annual population growth of 3.2% from 1992-1998. As a result of the Gulf crisis with the invasion of Kuwait, and the war that followed it, there was an estimated 10% growth in population in Jordan in a span of one year.

Table 7. Population % Growth

While having a look at the number of commercial companies registered with the Ministry of Trade and Industry, as shown in Table 8, it is noted that the total number of companies doubled in 1990 and 1991. These are companies engaged in one of the five major economic activities in the country, which included services, construction, agriculture, trade and industry. IT companies were listed under a combination of the service and trade sectors.

Table 8 shows that, the total number of registered commercial companies in Jordan more than doubled from 1,871 companies in 1989, to 4,281 companies in 1990, and again doubled to 8,445 in 1991.

Jordan, which is poor in natural resources, has been known for decades for exporting an educated labor force to the Gulf countries. The volume of the expatriate remittances back into Jordan before and after the Gulf crisis are as shown in Table 9.

Table 9 suggests that the remittances experienced some decline during 1990 and 1991 but picked up again in 1992, after which it continued to expand higher. The increasing numbers in remittances in 1992 and after, suggest an increasing trend in workers' immigration from Jordan.

The growth of the Jordanian labor force, is shown in Table 10.

As per Table 10, there was a dramatic increase in the labor force in the early 1990s. In 1992, there was a 14% increase in the labor force over 1991, and in 1993, there was an increase of over 2,59,000 new workers, a 43% increase over 1992. It took one year, from 1991-1992, before the impact of the immigrants showed up. Much of the returning labor force was initially unemployed, and as the returnees' investments spurred the economy into an expansion, new opportunities were created for those returnees who were unemployed.

As, The Government of Jordan (GoJ) faced the huge influx of people during the Gulf crisis, its infrastructure experienced a tremendous challenge, and the Government struggled with finding jobs for the returnees. According to El-Uteibi (1994), (p. 1), “the returnees were trying to cope with severe unemployment that has by then risen to over 30% since the beginning of the crisis”.

Table 11 shows the growth in the labor force in public administration and social services positions created by the GoJ.

Table 11 clearly shows that, the government managed to absorb over a 1,40,000 new employees in 1993, a 48% increase over 1992. Before the Gulf crisis, the new positions created by GoJ grew by less than 5% a year.

Let us see if the stock market had any unusual changes in its activities in the early 1990s. Table 12 includes the activities of all four sectors in the market (banks, insurance, services & industry) in the organized (primary) market.

Table 12 shows unusual activity in the value of trading in the stock market in 1992, where there was a 200% increase in the value of trading in the market in 1992 over 1991. Much of that increase was attributed to the returnees who were initially concerned with securing a home and a car upon their return, and then looking for opportunities for investments in the stock market and elsewhere.

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is a key economic indicator that measures, among other things, the growth and productivity of an economy. Table 13 shows how these numbers changed, if any, after the immigration of over 3,50,000 people from the Gulf to Jordan.

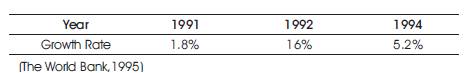

The Jordanian economy's growth % is seen in Table 14.

Table 14. Growth Rate of the Jordanian Economy. (According to 1985 Constant prices)

There is a phenomenal jump in the growth of the economy from 1991 to 1992, at an annual rate of 16%. The human and capital inflow into Jordan a year earlier created an unusual economic activity in the country. There was a boom in all sectors of the economy, especially in the construction and the manufacturing sectors, during 1991-1993 (Naser (2000), p. 42). The influx of people and money in the early 1990s stimulated the economy that had slowed down following the local currency devaluation in 1989.

Let us see how the economy responded with the influx of money into it in the first half of the 1990s. The Government deficit & surplus are shown in Table 15.

Table 15 shows that the Government of Jordan (GoJ) reversed the trend in its 1980s budget deficit and replaced it with a surplus starting in 1991, the first reversal ever since 1972. In 1992, the GoJ experienced a surplus of J.D. 181 million, the biggest surplus ever in the country's histor y. Apparently, it had more revenues than expenditures during the 1990s until 1997, and this is most probably tied to the influx of capital brought back by the returnees, which spurred the economy into a growth of 16% in 1992.

Let us next take a final look at the grants that the GoJ received to see if it had any major impact on the growth of the economy in the early 1990s.

Table 16 showed one unusual number (68% Increase) in 1989, when the GoJ decided to devaluate its currency. In 1991, there is another (37%) in the grants it received, but outside from these two years, there is no evidence of major grants pouring into the country during the early years of the 1990s, which could have reversed the deficit trend that had been going on in Jordan for nearly two decades.

It is noteworthy to mention that, the returnees impacted the social aspect of life in Jordan. For example, before their return, one would be hard-pressed to find an open shop or supermarket past 9 pm. After their return, however, the returnees promoted a culture of business at night, where coffee shops catered to customers past midnight, and supermarkets remained open until the late hours of the night and early morning.

“The immigration from the Gulf countries into Jordan had a positive impact on the growth of the whole economy in Jordan.” The factors that apply to this hypothesis are examined.

Table 6 showed the positive population growth after the immigration wave from the Gulf region. Also, the Tables 8,10,11,12,13 and 15 showed a similar positive growth within the same time span from 1989-1997. From Figure 1, a clear graphical correlation between the growth of the population and the growth of the economy, labor force, the stock market, and the number of registered companies is seen.

The testing hypothesis I shows that, the economy growth was strongly related to the growth of the population. Therefore, in conclusion, there was strong evidence supporting hypothesis I that, indeed, the returnees did impact the overall economy of Jordan.

“There is a perception that, the immigration from the Gulf countries into Jordan had a positive impact on the growth of the IT industry in particular in Jordan.”

From Figure 2, it is seen that 54% of the mean responses from the survey indicated an impact by the returnees on the IT industry, at least initially during the first few of years after their return.

According to Figure 2, there was some evidence that the “Return of IT professionals” from the Gulf impacted the growth of the IT sector in the country in the 1990s. Other factors were identified to have had an impact on the increase for IT services, especially the overall local demand for PCs with a mean response of 70%. The growth of the IT sector in Jordan could have been due to the natural growth of the IT sector and the resulting demand for PCs. Also, other factors were identified which had a weak impact on the increase in PC demand, which include: Internet proliferation starting in 1996, Y2K demand, standardization of the global IT industry and the availability of packaged IT solutions to meet growing corporate demands, and the continuous growth and demand from the Gulf region.

In conclusion, the immigration into Jordan had some impact on the growth of the IT industry in the country. The returnees caused a shake-up in the Jordanian IT market upon their return, introduced competition as well as opportunities by starting up their IT companies, and forced few changes in the market.

“There is a perception that the Jordanian government captured the momentum of the immigration influx and facilitated the business environment for the returnees in the early 1990s.”

The only visible government assistance to the newly established companies was in streamlining the registration of new companies. This assistance is supported by the fact that, 77% of the mean responses from the survey (Figure 3) indicated a faster registration process. The responders indicated that, they did not see much government assistance in the form of tax breaks, financial assistance, export assistance, incubators, improved intellectual property rights, or a free trade zone.

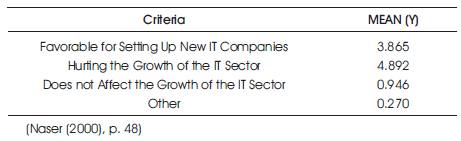

The growing demand from the local market, rather than government incentives, caused new IT companies to emerge in the market. Respondents from the survey showed a mean response of 80.5% (Table 17) for having expertise in the IT field as a reason to set up new IT companies.

Table 17. Reasons for establishing an IT Company

Furthermore, the growing number of new companies was fueled by factors such as the desire of business owners to be pioneers in the market, to capture new ideas to create a niche for themselves, and to own a profitable business. Other factors cited included the availability of cheap local IT labor, the market demand internationally as well as from the US for software services, and the opportunities to Arabize and develop software for the Gulf countries and to represent foreign companies in Jordan.

In conclusion, there was nothing to support hypothesis III, meaning that the Jordanian Government did not capture the momentum of the immigration influx and failed to facilitate the business environment for the returnees in the early 1990s, except for the hastening process of registering a new company.

“There is a perception in Jordan that, the government through its taxation system, bureaucracy, investment policies, and weak protection of intellectual properties contributed to the slow growth of the IT industry in the mid- 1990s.”

There was a mean response of 52.7% by survey respondents indicating that they pay excessive taxes to the government.

Almost half of the respondents believed that, they were paying too much in corporate taxes to the government. On the other hand, 29 of the respondents (78%) indicated that, they used to pay too much in tariffs for imported hardware that varied from 22% to 45% until the exemption in July 1999. Three (8%) of the respondents indicated that, they had to pay tariffs twice on the imported hardware that was defective and had to be sent back to the manufacturer for repair or replacement (Naser (2000), p. 125).

The piracy rate of software in the country was estimated to be around 85%. This figure was obtained as the Mean from the 37 surveyed companies when asked: “how much is the % of pirated software in the country,” with a score from 0-10, the Mean was 84.86% (Naser (2000), p. 65) .

It is noticed that, despite the high percentage of pirated software, only 54.3% of respondents said that their business was somewhat hurt by the weak Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) laws. This statement would be backed by a finding in the survey that weak laws allowed piracy, which allowed PC vendors to sell their systems at a relatively low price and compete in the local market (Naser (2000), p. 51).

There was no evidence that the government protected the intellectual rights of both local and imported software. Only 29.7% of mean responses indicated that, the government protected intellectual property rights.

There was a 48.9% (Table 18) mean response indicating that the investment climate in Jordan hinders the growth of the IT Sector.

Table 18. The Investment Climate in Jordan

In conclusion, there was mixed evidence for hypothesis IV, meaning that the Jordanian Government had an excessive taxing system (mainly in the form of tariffs), weak investment policies, the existence of intellectual property rights laws but weak protection and enforcement of those laws.

“There is a perception in Jordan that, there is a shortage of IT professionals due to their immigration from Jordan.”

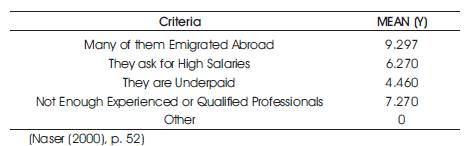

Table 19 looks at the status of the IT professionals in the market at the end of the 1990s.

Table 19. The Status of the IT Professionals in the Market Today

Table 19 shows a 92.9% mean response that, there was a shortage of qualified IT professionals and that many of them have emigrated outside Jordan. It also shows a 72.7% mean response that there aren't enough experienced or qualified IT professionals in the country in the late 1990s. There was a high employees' turnover rate in search of a better pay, and local talents emigrated abroad in search of a better life and higher salaries (Al- Ga'fari, 1995, p.15). Although there were 1500 computer science graduates with a bachelor's from local universities every year, these were mostly “quantity” talent, which needed to be transformed into “quality” talent (Naser (2000), p. 128).

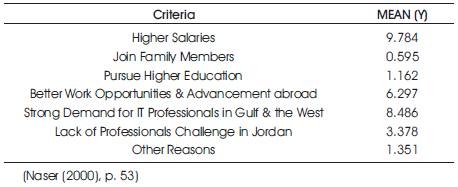

The reasons why IT professionals were leaving the country are given in Table 20.

Table 20. Reasons for IT Professionals' Immigration Abroad

Table 20 shows a 97.8% mean response that IT professionals leave abroad for higher salaries, 62.9% in search of better work opportunities and advancement abroad, and 84.8% because of the strong demand for IT professionals in the Gulf region and Western countries.

Other factors that were identified for the immigration of IT professionals abroad include, the desire to stay up-todate with the emerging technologies in IT, the better standard of living abroad, the overall poor economic situation in the country, and the small size of the local market with the growing number of college graduates each year.

In conclusion, there was supporting evidence for hypothesis V, meaning that there was shortage of IT professionals in Jordan.

It is evident from this research that, the return of IT professionals from the Gulf to Jordan following the Gulf War has impacted the social and economic fabric of Jordanian society. There is no definite quantitative approach to measuring exactly how much of an impact those returnees had on the growth of the IT industry in the 1990s. It is also known that, the returnees caused a boom to the overall economy shortly after their return as evidenced by the phenomenal growth of the economy in 1992. They also reshaped the Banking and Insurance sectors among others, created competition in the IT industry through their new IT firms and their demand for IT services. Also, they brought with them skills and managerial expertise that have spurred the growth of the IT sector and forced the acceleration of the concept of consultants, specialization, and salespeople in the local market.

The growth of the IT sector in the 1990s in Jordan can be attributed to a host of factors aside from the returnees. These factors include, the global standardization of IT solutions and products, financial investments in IT divisions of large institutions like banks and insurance companies, the aggressive marketing of big international IT companies in the regional market, and the availability of local talent to take on such projects as Arabization of foreign software and programming tasks for Western companies. Furthermore, the Internet proliferation and Y2K demand during the second half of the 1990s fueled the demand for more IT services and products, and there were a natural computerization and growth process in the country which also helped to fuel the local demand during the 1990s decade.

The government was passive at best in taking advantage of the capital and "know-how” brought back by the returnees and it instituted new taxation laws that hurt the entire IT industry for most of the 1990s decade. It was mired in a "taxation” mentality, which provided the main part of its fiscal budget, and had a huge bureaucratic establishment, especially at the Customs Department, which made it very challenging for the IT industry to operate in a timely and profitable fashion.

Weak IPR laws meant there was no practical protection for either originally developed software, nor for legally purchased software like Microsoft products. With weak IPR laws, IT companies didn't charge too much for software, since a lot of it was pirated. Another weak law was the Labor Law, where part of it states that, a hired employee who develops software for a company can claim 50% of the value of that software for himself (Naser (2000), p. 95).

The government also was not paying enough attention to the issue of intellectual property rights which led to a high piracy rate, up until after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in late 1999. The late response in the amendment of IPR law in 1998 (Jordanian Copyright Law, 1998) had cost the country a loss of jobs and revenues, not to mention skills, from international IT firms that could have been based in Jordan, had the IPR laws been on par with international standards.

One thing to be credited to the government in the 1990s, though is its miraculous ability to continue to offer the basics in its infrastructure to citizens, despite the enormous pressures, it has experienced as a result of the return of the expatriates. It has managed to absorb over 1,00,000 of the returnees through employment in the public sector ( Table 11. Public Labor Force), and to keep its economy growing, although slowly, and it was taking steps to privatize some of its public entities like telecommunications.

The GoJ realized there was work that needed to be done in order to remedy the weak state of the IT sector in the country. In June of 1999, King Abdullah II of Jordan requested a concrete proposal aimed at strengthening Jordan's IT sector from the IT industry leaders. In response, a core group of members of the Jordan Computer Society (JCS) (1999) devised the REACH initiative (The REACH Initiative, 1999), a comprehensive framework that embraces actions in terms of:

Relatively recent success stories of well-known Jordanian companies at an international level could be, directly or indirectly, attributed to the immigrants from the Gulf countries to Jordan after the Gulf War. The success stories include such names as Maktoob and Rubicon, two Jordanian companies that were set up in the 1990s that became renowned a decade later.

In 2009, Yahoo acquired the Jordanian Arab Internet portal Maktoob for $164 million. Maktoob was launched in the late 1990's as the first free Arabic Email service provider. After the Maktoob acquisition, its founders went on to accomplish other renowned businesses such as Souq.com, the Arab world's largest online retailer, based in Dubai's Internet City (Gara, 2012).

Rubicon, the animation, and entertainment firm that had the largest 2D and 3D animation studio in the Middle East was originally set up in Jordan in 1994. It turned into an international brand name by the name of the Rubicon Group Holding in 2004. It worked with MGM Studios in the US to produce an animated television series based on the Pink Panther franchise of films. Rubicon was dubbed as “The Pixar of Arabia.” In 2009, Bahrain-based private Equity firm, GrowthCapital had acquired 30% of Amman-based Rubicon (Another Acquisition, 2009).

There were several cultural impediments to the growth of the IT sector. Examples of those included the reluctance of college graduates to accept sales or marketing related jobs in firms. This reluctance could have been overcome once the salaries of people working in those two fields exceed the salary of technical personnel engaging in programming services, which would get the attention of ambitious and aggressive graduates and force a change in the industry.

The culture in Jordan is still a male-dominated one, and all the IT companies that were surveyed were run by males. Pertinent to the same issue is the pay scale difference between female and male IT professionals.

The fact that there was no appreciation for software value by both individuals and local companies indicates a fundamental lack of understanding of the value of such a non-tangible product. This is explained in the context that many of the Arab cultures including the Jordanian derive much of their heritage from the desert climate, which favors tangible possessions and assets (Hodgetts & Luthans, 1991). This lack of appreciation towards software had attributed to the high piracy rate in the country in the 1990s (Naser (2000), p. 135).

One cultural issue was the absence of mergers and acquisitions in the IT industry. The concept of mergers and acquisitions between compatible companies was still a foreign concept in Jordan. People tend to set up their companies to gain status in society, among the other obvious reasons, and it is not an easy task to change that mentality. One possible approach to addressing this issue is by accepting a third, non-Jordanian party, which could be acceptable to the Jordanian parties to consolidate two or more companies together.

Another important issue is that in Jordan, there was still no concept of billing by the hour across all types of businesses and professions. People tend to see tasks as chunks and assign a value to complete each one of them, and because of the low-income levels in the country, the concept of billable hours had not been feasible (Naser (2000), p.132).

The research results were mixed. Some of the results indicated the growth of the IT sector in the 1990s may have been spurred by factors such as: global standardization of IT solutions and products, financial investments in IT divisions of large institutions like banks and insurance companies, aggressive marketing of big international IT companies in the regional market, and availability of local talent to take on such projects as Arabization of foreign software and programming tasks for Western companies. Also, the Internet proliferation and Y2K demand during the second half of the 1990s fueled the demand for more IT services and products.

Other implications of the research indicated to the existence of cultural challenges that could impede the growth of the IT sector such as those limiting mergers and acquisitions. The returnees caused a boom in all sectors of the economy and especially in the construction and the manufacturing sectors during 1991-1993 shortly after their arrival as evidenced by the phenomenal 16% growth in the economy in 1992. They created competition in the IT industry and brought technical skills and managerial expertise that gave a boost to the IT sector and forced the acceleration of local market concepts such as consulting, specialization, and marketing.

Although Jordan had experienced a substantial capital inflow of (US$ 2-3 billion), as a result of this there was major influx of people into the country, its government failed to take full advantage of this momentum. Instead, Jordan's government through its taxation system, bureaucracy, investment policies, and weak protection of intellectual properties contributed to the slow growth of the IT industry in the mid-1990s.

It is hopeful that as a result of this research, some countries, be them developed, developing or less developed, would benefit today from Jordan's experience in dealing with this diverse wave of immigrants of the early 1990s, and end up with similar success stories to Maktoob's and Rubicon's.