The college student population in USA is predicted to increase from 13 million to 21 million between 2003–2015 (Strom & Storm, 2004). This increase along with the exponentially increasing cost of post-secondary education has caused an increase in the financial burden placed on students. Between 2000 and 2012, the two major post-secondary institutions in the South eastern state of USA, where the study was conducted has raised their tuition rates almost 200 percent (Bennett & Wilezol, 2013). The present study used a quantitative approach to determine the relationship between student's financial contributions and student motivation. Student financial contribution was determined by students' personal contributions (loans, scholarships, full and part-time work, and student savings) toward tuition, fees, books, housing, and transportation. The survey was distributed using the College of Education, listserv through the Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. This study found that, there is a significant statistical relationship between student financial contribution and intrinsic goal orientation.

Counselors, teachers and parents consistently encourage teenagers to strive toward a college education. The college population is predicted to increase from 13 million to 21 million between 2003 and 2015 (Strom & Strom, 2004). There is concern that this increase in tuition is gradually beginning to price the middle class out of post-secondary education. Middle class families feel that, college is a road to success and that 'blue collar' jobs are losing their prestige. Currently, 18 million students in USA are pursuing two or four year degrees. Another 2.9 million students are attending graduate schools (Selingo, 2013). Each year these numbers are increasing. Student loan debt has increased forty-five percent since the early 1990s. The top ten percent of borrowers owe more than $54,000 (Selingo, 2013).

Some students are not the sole contributors to their postsecondary education. Many parents and other family members assume the burden of student post-secondary debt (Selingo, 2013). These staggering statistics raise significant questions such as: How does this lack of future responsibility affect students? Does it hinder their motivation?

The present study sought to identify the effects of increased post-secondary expenses on the average student, as well as the effects of student financial contributions to their educational experience on their motivation.

As time progressed, more students began to attend college. According to the College Board, in 2008 around half of all 18–21 year olds were enrolled in college (Digest of Educational Statistics, 2009). As more students began filling the seats of Colleges and Universities, tuition rates started rising inversely with the economic downturn. Tuition at Auburn University more than tripled over a twelve-year period from 2000 to 2012, ballooning from $3,154 to $9,446 (Bennett & Wilezol, 2013). The federal money influx slowed, necessitating the increase in tuition prices for Colleges and Universities.

Other students use parental aid to get through school. Parents of various income levels can provide different levels of financial aid for their children's education. They make difficult financial decisions to ensure that, their children have the opportunity to attend college. Parents who contribute significantly to the cost of their child's postsecondary education may create conditions that decrease a student's GPA but increases his/her graduation rate (Hamilton, 2013). The present study attempted to expand upon these ideas by looking at the effects of the student financial contribution on student motivation as these variables have been shown to be related to academic success because they lead to academic success.

Post-secondary expenses are comprised of room and board, tuition and fees, books and supplies, personal expenses, and transportation. Tuition is the most costly of the five categories. Tuition is determined by the residency status of the student and is often classified as in-state or out-of-state tuition. The rationale for this difference is that students who live in-state contribute to state income tax through their parents. In-state tuition is determined by two ways: (1) by a college board, and (2) by the state legislature (Fethke, 2006). Tuition is a major factor when students choose a college (Dotterweich & Baryla, 2005). Many studies focus on the rise of college tuition during the last decade in the United States.

Students mistakenly assume that, because a university has high tuition, it offers quality education; therefore, students expect a higher salar y at Graduation (Dotterweich & Baryla, 2005). Many studies focus on student retention and graduation rates of colleges and universities, but these studies do not focus on the role that tuition plays in their graduates' academic successes.

In today's economy, more students are entering universities; so understanding tuition is important (Mullen, Goyette & Soares, 2003). As tuition rises, students incur more debt. Due to this debt, graduates and nongraduates have to delay major purchases (such as home ownership) because they are paying off student loans (Bennett & Wilezol, 2013). The federal government subsidizes some loans for students. They offer a lower interest rate than un-subsidized loans, which are susceptible to market fluctuations (Stack & Vedvik, 2011).

The paucity of research in the field of student financial contribution affecting student motivation in postsecondary education is addressed by this study. Limited research has been conducted by Hamilton (2013) on the effects of parental aid on student GPA using a national data set; but the study did not address how parental aid affects student motivation and learning strategies. Zhang (2007) has conducted a research on the effects of student debt on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. This study elucidates the effects of the student financial contribution toward student post-secondary experience on student motivation among students enrolled in the College of Education at a large South eastern University during the 2014 summer semester.

Further, it is hoped that, this study may provide insight into how student financial contribution toward postsecondary experience affects students in the classroom. This research further seeks to provide insights into how these variables can help inform legal policy makers and universities about what can be done in the United States to ensure that, post-secondary education stays affordable for the middle class and that the cost to students has the smallest effect on their academic success as possible.

Using a quantitative approach, this study attempted to determine the impact of the student financial contribution toward post-secondary experience and its effect on student motivation. A very limited amount of research has addressed the impact of student financial contribution toward their post-secondary experience and its effect on student motivation. This study attempted to replicate certain aspects of Hamilton's (2013) study and expand upon its basic tenets. Zhang (2007) found that student's intrinsic motivation is improved when they borrow money for post-secondary education. To date, and to the best of the author's knowledge, no researchers have looked at the impact of student financial contribution toward post-secondary experience and its effect on student motivation. The following research questions were explored.

(1) Does student financial contribution toward postsecondary educational experience predict intrinsic goal orientation among students who are enrolled in the College of Education?

(2) Does student financial contribution toward postsecondary educational experience predict extrinsic goal orientation among students who are enrolled in the College of Education?

(1) There is a positive statistical relationship between student financial contribution toward their postsecondary educational experience and intrinsic goal orientation among students who are enrolled in the College of Education.

(2) There is a positive statistical relationship between student financial contribution toward their postsecondary educational experience and extrinsic goal orientation among students who are enrolled in the College of Education.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2010), 79% of all undergraduate students in 2008–2009 received financial aid. Keeping in mind these statistics were during a period of recession, it is a considerable percentage. Financial aid is defined as public assistance from the government. Undergraduates with family incomes that are below the poverty line in the United States receive this in the form of Pell Grants, which do not have to be repaid. Public assistance helps offset the cost of post-secondary schooling in the United States and helps to improve student retention.

According to the Auburn University website, students who are considered Alabama residents would pay an average of $28,098 per year to attend the University. The financial breakdown is as follows: tuition and fees – $9,852; room and board – $11,552; books and supplies –$1,200; transportation – $2,816; and personal – $2,678. Non-residents would pay $44,610. The financial breakdown is as follows: tuition and fees – $26,364; room and board – $11,552; books and supplies – $1,200; transportation – $2,816;and personal $2,678 (Auburn University, 2014).

Motivation is the desire to complete a task and is critical to the college and university student’s academic success (Anderson & Keith, 1997; Dweck & Master, 2009; Schunck & Zimmerman, 1994; Wentzel & Wigfield, 2009). Student motivation in post-secondary education is an important aspect; because it dictates the desire of students to complete college. The cost-benefit of college is viewed positively when the economic climate allows graduates to obtain jobs in their field. Motivation can be a somewhat ambiguous concept to measure, in part, because every student is motivated differently

According to Moen and Doyle (1978), the most difficult task of this type of study is determining how much motivation students have and how students with high motivation and low motivation differ when answering certain types of questions. Intrinsic motivation is more desirable for students, because it allows them to motivate themselves without external stimuli. Students must learn to self-regulate their behavior; because external motivation eventually extinguishes (Mishel, Shoda, & Rodrigeuz, 1989). The ideal student would be internally motivated and therefore desire to continue learning simply for the knowledge to be gained.

Gredler (2009) suggested that rewards should be limited because students will only respond while the rewards are present. Gredler (2009) found that, after the initial interaction with the reward, two things begin to control the response of the subject: (a) the behavior itself (speech), and (b) the internal stimuli. The goal would be to limit the external factors that might hinder internal motivation.

Traditional younger college students, who are still adolescents, need a combination of situations to become academically successful and are more driven by external factors (Wolfgang & Dowling, 1981). Older learners in their 20s and 30s are still susceptible to an extrinsic motivator but; are found to be more cognitively invested in what they are learning, because they find more practical use for the information (Wolfgang & Dowling, 1981). It is possible that, assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivation could help to retain and identify students who are at-risk for dropping out. Intrinsically motivated students tend to perform better in school, because they do not rely on the external factors of many adolescent learners (Wolfgang & Dowling, 1981) .

There are many non-malleable environmental characteristics that affect student motivation in school such as the following: socio-economic status, parental educational level, race, and gender (Walker, Greene, & Mansell, 2006). Byrnes (2003) found that, these nonmalleable factors will not decrease the risk factors of students academically, and researchers should focus on malleable factors that can be changed; hence, student financial contribution toward tuition affects student motivation. Dillon and Greene (2003) also found focusing on research that cannot be controlled gives researchers little understanding of what students can change academically to become academically successful. Identification of students who are driven by external factors will allow for universities to help to promote intrinsic motivators for students to achieve a higher level of performance.

Intrinsic motivation was first identified by White (1959) while studying organisms. He realized that, many animals engage in behaviors for enjoyments, even if the activity lacks reward or reinforcement. Intrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it creates joy or is interesting (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Intrinsic motivation sub-theory of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has been traditionally measured in two ways: self-report of the individual and through experimental methods. Self-report participants are asked to identify their level of enjoyment of an activity (Ryan, 1982) . In a study conducted by Deci (1971), the researcher measured intrinsic motivation based on “free choice.

”Participants were exposed to a task then instructed that they no longer needed to complete the task. If the participants chose to complete the task, it was defined as “free choice.” Then, Deci (1971) measured the level of intrinsic motivation based on the amount of time the participant spent on the task without reward. In the classroom, intrinsic motivation is important, because it is the vehicle for students learning. “Intrinsic motivation results in high-quality learning and creativity, it is especially important to detail the factors and forces that engenders versus undermines it” (Ryan & Deci, 2000) .

Extrinsic motivation is the desire to complete an activity based on an external stimuli. According to Deci and Ryan (1985), organismic integration the oryis broken down into four categories: externally regulated behavior, introjected regulation of behavior, regulation through identification, and integrated regulation. Externally regulated behavior is based on the promise of a reward. The acceptance of a behavior as a way to regulate one's personality is introjected regulation of behavior. Regulation through identification is an action that is personally important. Integrated regulation is the full assimilation of a belief by an individual (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Throughout an individual's life span, he/she can internalize different aspects of social values and regulations based on his/her specific desires and situations (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

The present study is a quantitative study that utilized an online survey method. A survey was used to collect parental financial information, course load information, and students' means for paying for their post-secondary experience. The survey was also comprised of various subsections of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ), (Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, & McKeachie, 1991). All students of nineteen and older enrolled in the College of Education during the 2014 summer semester had a chance to participate in the survey via a College of Education listserv.

The MSLQ is an eighty-one item self-report measure that gauges a person's motivation and self-regulated learning. It was created from 1982 through 1986 National Center for Research to Improve Post-Secondary Teaching and Learning Grant (Pintrich & Garcia, 1991). Using 1,000 University of Michigan students, McKeachie and Pintrich fine-tuned the MSLQ. The revisions to the MSLQ took place in three waves during1986, 1987, and 1988 (Duncan & McKeachie, 2005). The instrument was created to collect data from college students about their motivational orientation and learning strategies. Duncan and McKeachie (2005) found that, “the MSLQ was developed using a social-cognitive view of motivation and learning strategies, with the student represented as an active processor of information whose beliefs and cognitions mediated important instructional input and task characteristics” (p.117). Thus, student motivation depends on the specific task in which students are participating and the students' self-efficacy and interest.

The study was limited, because it only focused on students over the age of nineteen in the College of Education. The survey was also distributed during the summer semester 2014. The sample for this study was a convenience sample. Participants were not randomly selected; they were self-selected as participants through the online survey. Therefore, these participants may not reflect the general population. Edwards (1957) also proposes that, students respond to surveys based on their need for social desirability. Social desirability is the need to receive approval and acceptance from peers. This causes many concerns regarding the validity of self-report surveys. Winne and Perry (2000) found that, when students are asked to self-report, they cannot be completely objective. Self-report leaves open the option for misinformation, even though it might not be intentional.

The study used a quantitative design that, utilized a survey and asked students over the age of nineteen who were enrolled in the College of Education to participate. In the state that the study was conducted, students under the age of nineteen may not participate in research studies without parental consent. They were also chosen because college freshman does not have a firm grasp on their financial situation (Simpson, Smith, Taylor, & Chadd, 2012).

Data was collected via survey through the Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. An e-mail was sent to all undergraduates enrolled in the College of Education during the 2014 summer semester. The initial survey was followed by two subsequent reminder e-mails to encourage participation. Following the final reminder, professors in the College of Education teaching summer courses with undergraduates were contacted via e-mail to ask if they would allow the researcher to visit their classes to encourage participation. The researcher visited classes and students were encouraged via a verbal reminder to complete the survey.

The instrument was comprised of financial information, and sections of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ); Pintrich, Smith, Garcia & McKeachie, 1991). Students were asked via a self-report survey about the average course load, number semesters in school, number of semesters until graduation, student GPA, parental income, and percentage of parental and student financial contribution toward their post-secondary experience. Student levels of contribution toward their post-secondary experience were determined based on the following: student employment, scholarships, loans and personal savings.

The study utilized three subscales from the MSLQ motivation. Each subscale is divided into sections. The motivation subscale includes intrinsic goal orientation, extrinsic goal orientation, and task value. Student financial contribution was a percent based on students' contribution toward their post-secondary educational experience. It included: loans, scholarships, personal savings, summer employment, and employment during the school year. The MSLQ scales were scores based on the average across items measuring the construct and that the participants responded on a 7-point Likert-type scale. To assess validity, Pintrich used a confirmatory factor analysis (Pintrich, Smith, Garcia & McKeachie, 1991). The three value components that the researcher utilized in this study have Cronbach alphas that are as follows: intrinsic goal orientation = .74, extrinsic goal orientation = .62.

The participants in the study were nineteen years of age or older and were enrolled in the College of Education during the 2014 Summer Semester. The survey included 64 participants. Income data were collected based on the 2013 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax bracket. Three percent (3%) of the student population reported that their parents made between $0–8,925, 9% of the student population reported that, their parents made between $8,926–36,250, 19% of the student population reported that, their parents made between $36,251–87,850, 54% of the student population reported that, their parents made between $87,851–183,250,9% of the student population reported that, their parents made between $183,251–398,350 and 7% of the student population reported that, their parents made $398,351 or more. On average, the majority of participants said their parents and family contribute 59% of the cost of their postsecondary experience. This was followed by student loans (17%) then scholarships (12%).

The majority of the students were junior or seniors in the College of Education. Of the students, who responded to the survey, 14% had been in school for six semesters; 20% had spent seven semesters in school; 9% had spent eight semesters in school; and 26% had been enrolled in school longer than ten semesters. Sixty-six percent (66%) of the students had less than two semesters until graduation.

Prior to testing the data, an initial screening for missing data was conducted to identify gaps. Only surveys of students who were over the age of nineteen were used in the study (n=64); others were discarded (n=6). The subscale questions were averaged together to create a variable average score. Those who were missing data from one question in the subscales had the missing data omitted and the remaining questions in that subscale section were averaged to create the variable average score.

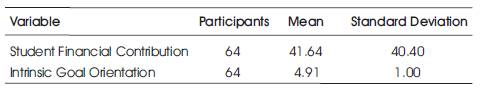

A simple regression analysis was used to address the research question asking whether or not the student financial contribution predicted students' intrinsic goal orientation using the MSLQ. Student financial contribution was measured as a percentage of student's contribution toward their post-secondary educational experience. Intrinsic goal orientation represents the average of four items measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The results indicated that, the weak positive relationship exists between student financial contribution and student intrinsic goal orientation r = .293). For each one-point increase in the student financial contribution, a 0.007 increase in student intrinsic goal orientation is seen (b=.007, p=.019). The coefficient of determination (r2 = .086) indicates that, approximately 9% of the variance in student extrinsic goal orientation can be accounted for by its linear relationship with scores from student financial contribution towards their post-secondary experience. Table 1 shows the intrinsic goal orientation.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Variable Means and Standard Deviations: Intrinsic Goal Orientation

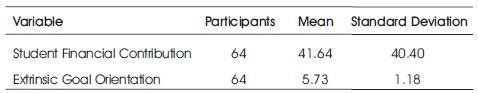

Extrinsic goal orientation represents the average of four items measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale. contribution toward their post-secondary educational experience. The results indicated that no relationship exists between student financial contribution and student extrinsic goal orientation, r = .166, b= .005, p= .189. The coefficient of determination (r2 = .028) indicates that approximately 3% of the variance in student extrinsic goal orientation can be accounted for by its linear relationship with scores from student financial contribution towards their post-secondary experience. Table 2 Show the extrinsic goal orientation.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Variable Means and Standard Deviations: Extrinsic Goal Orientation

The present study was conducted using a survey research methodology. The survey was distributed through the Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. The participants were sent an initial email with two follow-up emails. There were sixty-four complete responses. The results reflected students' contributions to their postsecondary educational experience and their motivation.

Student intrinsic motivation was found to be statistically significant (p=.019) finding that, the more that students contribute financially toward their post-secondary experience, the more intrinsically motivated they become. No other statistically significant findings were revealed during the present study based on the research questions presented.

The study did not find any significant findings involving the other MSLQ subscales that were analyzed in the present study: extrinsic motivation (p=.189). However, the lack of significant findings did reveal many interesting facts regarding the effect of motivation on students. One such factor is that there is a lack of change in student extrinsic goal orientation. Both students who have their postsecondary experience paid for by their parents and those who pay for their own post-secondary experience are equally extrinsically motivated.

Ryan and Deci (2000) found that, intrinsic motivation results in high-quality learning and creativity. By identifying these students, universities could implement interventions to end the proliferation of reliance upon extrinsic motivators to create better learners. Therefore, interventions that shift the mentality of learners from extrinsic to intrinsic would provide a service to the learner.

The results were reflective of students who contribute financially toward their post-secondary experience are more intrinsically motivated (p= .019) than thier peers. No other statistically significant findings were revealed during the present study based on the research questions presented. Extrinsic motivation was found to be not statistically significant at p= .189.

Based on the provided analysis, intrinsic motivation is effected by student contribution toward their postsecondary education. However, the lack of significant findings did reveal that there is a lack of change in student extrinsic goal orientation. Both students who have their post-secondary experience paid for by their parents and those who pay for their own post-secondary experience are equally extrinsically motivated. This revelation in the research would be an area for further research.

The present study found that intrinsic motivation (p=.019) was found to be statistically significant. This study has found that students who contribute toward their postsecondary educational experience have increased intrinsic motivation. This is important because students with higher intrinsic motivation are more likely to perform better in school (D'Lima, Winsler & Kitsantas, 2014; Freudenthaler, Spinath, & Neubauer, 2008; Hamilton, 2013). This implication that students with higher intrinsic motivation perform better in school would lead the researchers to believe that if students contribute more towards their post-secondary educational experience, they will be more academically successful. This might also serve as a guide for parents, university officials, and other invested parties to encourage a level of student financial contribution to help students increase their intrinsic motivation.

This increase can also be explained because students learn best when the material they are learning has personal meaning and is tailored to their particular interests (Zemke & Zemke, 1988). The students who participated in the present study were enrolled in the College of Education and working on their college majors and would have found more interest in the material they were studying, therefore, increasing their intrinsic motivation. The present study found that as student personal spending on post-secondary education increases, so does their motivation to learn. This is a novel idea that corroborates the accepted thought that intrinsic motivation is very beneficial to students academically (D'Lima, Winsler & Kitsantas, 2014; Freudenthaler, Spinath, & Neubauer, 2008).

Student extrinsic motivation is found to be a bi-product of the high school system in the United States. Students are rewarded with grades and credit for advancement. However, as most students travel through their college careers, those who are extrinsically motivated either dropout or change their motivational strategies to become academically successful (Thompson & Thornton, 2002). College courses are more tailored to student's particular interest and, therefore, increases students' intrinsic motivation. This was found true in the present study, because the majority of the students were at the end of their college careers and were enrolled in classes that tailored to their particular majors, which would lead them to be more intrinsically motivated, thus lowering their extrinsic motivation.

Based on the literature review, there are many different facets of financial motivation. This study determined that, the student financial contribution toward their postsecondary experience does predict student intrinsic goal orientation (p = .019). Students who contribute to their post-secondary educational experience are more intrinsically motivated. Therefore, they are more invested in the learning process and find value in what they are learning.

Most importantly, it provides insight into the effects of the student financial contribution toward post-secondary education on student motivation. To the best of the researcher's knowledge, there remains a paucity in the research on the effects of the student financial contribution toward their post-secondary educational experience. By attempting to fill the void, this study has found that students who contribute toward their postsecondary educational experience have more intrinsic motivation. This is important because students with higher intrinsic motivation are more likely to perform better in school (D'Lima, Winsler & Kitsantas, 2014; Freudenthaler, Spinath, & Neubauer, 2008; Hamilton, 2013). This implicate that students with higher intrinsic motivation perform better in school would lead the researchers to believe that if students contribute more towards their postsecondary educational experience, they will be more academically successful. This might also serve as a guide for parents looking to fund their students' post-secondary educational experience by encouraging them to take the 'less is more' approach to educational funding that was proposed by Hamilton (2013). More research needs to be conducted to expand upon these ideas.

A longitudinal study would expand upon the ideas of this study by looking at the long-term effects of the student financial contribution toward their post-secondary experience and job preparedness or future earnings would provide interesting insight into the long-lasting effects of student financial contribution. A follow-up study that encompasses all academic majors would also provide a holistic view of the impact of student financial contribution toward post-secondary education.

The steep increase in tuition is a new phenomenon that has occurred in the last few decades. As more people attend college and the demand to do so increases, so does the cost. This area has not been fully investigated, and this study attempted to help fill that void by providing vital information toward the understanding of many different facets of the issue. In conclusion, this study has found that as students contribute more toward their postsecondary experience, their intrinsic goal orientation increases. There is a direct financial link between student intrinsic goal orientation and student financial contribution toward their post-secondary experience, thus allowing for deeper understanding and retention of learned material. Students, parents, and other interested parties should take this into account when paying for postsecondary education because the presence of intrinsic goal orientation signifies the higher academic success and learning.