Grounded on the tradition of Contrastive Rhetoric (CR), this paper aimed at contrasting the presence of metadiscourse resources in a book preface of Filipino and English authors. It especially sought to see the similarities and differences of interactive and interactional markers between two cultures. A total of thirty book prefaces on language areas, fifteen in each culture were culled. They were identified, classified, and interpreted based upon the taxonomies by Hyland and Tse (2004) with the interlarding frameworks by Crismore, Markkanen, and Steffensen (1993); Hyland (2007); Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik (1985); and Yagiz and Demir (2015). Results show that a book preface is calibrated by authors from both cultures with a profuse use of interactional MD resources, that is, a book preface has to be more interactional than interactive. The results also put forth that differences in metadiscourse resources reside in the text due to the differing cultures of individualism and self-accolade among the English, and humility and text-economy among Filipino authors. In a nutshell, practical and pedagogical implications are offered in this present study.

The maiden work of Kaplan (1966) on Contrastive Rhetoric (henceforth CR) some forty-nine years ago was an attempt at solving pedagogical problems related to the ESL/EFL writing discipline. His seminal article, “Cultural thought patterns in intercultural education” serves as the springboard to many of today's contrastive rhetoric studies. This is grounded on the motherhood idea that no two or more languages share exactly identical rhetorical styles (Hinds, 1983), and the organization of ideas in writing vary from one speech community to another because of cultural differences that take place (Kachru, 1999) . Indeed, results from local and international studies exemplify the fact that although there are similarities, differences are prevalent due to some factors.

To date, CR has branched out interesting studies which are not only related to pedagogical concerns. In fact, this field of inquiry is also in filtrating in the world of discourse analysis, textual types and other genre analysis which continue to attract a great deal of attention among researchers. Contrastive studies include criminal appeal cases (Brylko, 2002); news leads, advice columns, and news stories (Gustillo, 2002; Laurilla, 2002; Scollon, 2000); argumentative essays (Connor,1984), persuasive essays (Connor & Lauer, 1985); introduction sections of textbooks (Kuhi, Tofigh, & Yavari, 2013; Zhu, & Gocheco, 2014); master's thesis introductions (Lintao, & Erfe, 2012); research articles (Pooresfahani, Khajavy, & Vahidnia, 2012; Sultan, 2011); conclusions in research articles (Morales, 2012); and complaint letters (Madrunio, 2004). Moreover, contrastive studies are also taking place in grammatical structures of two languages such as transitional markers (Elahi, & Badeleh, 2013), request strategies (Han, 2013), cohesion (Genuino, 2002; Mohamed, & Omer, 2000), prepositions (Jafair, 2014), first personal deixis (Su, 2010), business and technical professions (Woolever, 2001), cross- cultural technical communication (Wang, 2008), including the areas of reading, i.e., reading strategies (Wang, 2011).

“Metadiscourse is a self-reflective linguistic material referring to the evolving text and to the writer and imagined reader of that text” (Hyland & Tse, 2004, p. 156). It looks into the writers' discourse that signals their attitude towards the context and the intended audience of the text. It is also an enterprise that looks into the senders' personalities, attitudes and assumptions, not just only about mere exchange of information. Thus, metadiscourse facilitates communication and supports the position of a writer, hence establishing a writer-reader interaction (Hyland & Tse, 2004) .

Metadiscourse (MD), coined by Zellig Harris (1959, as cited in Hyland, 2005), represents writer/speaker- receiver/ audience relationship. Although the first taxonomy was only introduced some thirty years ago by Vande Kopple's (1985), metadiscourse has attracted a number of researchers who have focused their attention to written texts representing various genres and disciplines (Behnam & Roohi, 2012). By now, the growing number of taxonomies is underway (Crismore, Markkanen, & Steffensen, 1993; Hyland, 1998; Hyland, 1999; Vande Kopple, 1985); Hyland, 2004; Hyland & Tse, 2004; and Adel, 2006).

Also, MD is an ideal framework to compare the generic practices employed by the writers, and to explore different rhetorical patterns and preferences among various discourse communities, whether from the inner, outer, or expanding circle of English users. Looking into the different metadiscourse patterns can help the readers distinguish discourse communities as regards the way writers clarify their intentions in the texts (Hyland & Tse, 2004) .

However, metadiscourse is a “linguistic material that does not add propositional meaning to the content but signals the presence of the writer” (Vande Kopple, 1985, p.83). Crismore, Markkanen and Steffensen (1993) support that, MD is characterized by its non-additive nature, that is, it does not add anything to the propositional being presented. Put another way, interactive metadiscourse markers refer to the way the writer manages the flow of information of the text. These signals are capable of engaging the readers on the formal level of grammar (Heng & Tan, 2010). Whereas, interactional/interpersonal resources refer to the way the writers explicitly intervene by commenting on and evaluating the material (Thompson, 2001). This characterizes the kind of writer-reader interaction that is intended to take place (Hyland & Tse, 2004).

Some literature provides interesting metadiscourse studies as regards comparative rhetoric between two or more cultures. These research studies investigated some similarities and differences vis-à-vis these two major metadiscourse features. Comparisons on research articles, theses and dissertations include the Arabic and English abstracts for English research articles in applied linguistics (Alotaibi, 2015); the native speakers of English vs. native speakers of Arabic's discussion and conclusion chapter in doctorate theses (Alshahrani, 2015); the Iranian writers in medical journals (Ghadyani & Tahririan, 2015); the introduction section of research articles by both native English and Chinese speakers (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014) ; the English and Iranian dissertations from four disciplines such as applied linguistics, medicine, computer science, and business studies (Behnam & Roohi, 2012); the English and Iranian research articles produced by the applied linguistics and engineering group (Pooresfahani, Khajavy & Vahidnia, 2012); and the Persian and English research journals in applied linguistics and computer engineering (Zarei & Mansoori, 2011).

Moreover, the enterprise of metadiscourse is also used in contrastive rhetoric studies in other genres of writing. First, they include the persuasive writings of Indonesian EFL learners compared to the British corpus (Rustipa, 2014); the persuasive essays of British and Malaysian students (Heng & Tan, 2010); and the persuasive essays of American and Finish students (Crismore, Markkanen, & Steffensen, 1993). Second are the genres of newspaper and textbooks: the news articles written in the USA and Iran about the 9/11 attack (Yazdani, 2014); the hedges and boosters used in US newspapers regarding the 9/11 attack (Yazdani, Sharifi, & Elyassi, 2014), including the introductory textbooks and scholarly textbooks written by Anglo-Americans (Kuhi, Tofigh & Yavari, 2013).

Other sets of evidence show intra-cultural investigations such as the persuasive essays of Malaysians (Tan & Eng, 2014); the Iranian Chemistry engineering students' compositions analyzed using two MD resources (Davaei & Karbalaei, 2013); and the Malaysian argumentative essays, analyzed using both MD resources (Luyee, Gabriel, & Kalajahi, 2013).

While two major MD resources were analyzed simultaneously, some researchers resorted using specific markers, either interactive or interactional/interpersonal. Reviewed studies include code glosses in English texts written by native English, and English texts written by Iranians, and Persian texts written by the Iranians (Rahimpour, 2013); hedging and boosters among Japanese, Turkish and Anglophonic research articles (Yagiz & Demir, 2015); intensity markers observed in research articles by applied linguistics and electrical engineering writers (Behnam & Mirzapour, 2012); the abstract and conclusion in research articles (Behnam & Mirzapour, 2012); the transitional markers in research articles in English written by native English and Persian academic writers (Elahi & Badeleh, 2013); and the interactional markers among students' essays (Yazdani, 2014).

Understandably, many of the MD studies, that is, contrastive rhetoric studies reveal similarities and differences. This is due to the interplay between and among multi-level analysis systems, the combination of linguistic, cultural, educational, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistic perspectives (Connor, 1984; Halliday, 1994) , political factors, including the discourse community who reads and interact with the texts—all constitute the context of writing (Matsuda, 1997).

For example, in the discipline of applied linguistics and medicine, the least frequently used interpersonal resources were attitude markers and self-mentions (Behnam & Roohi, 2012). By and large, the use of textual and interpersonal metadiscourse markers in dissertations was more prevalent among the native English writers than that of the Iranian writers (Behnam & Roohi, 2012). Alshahrani (2015) maintains that the differences occur between soft (e.g. linguistics) and hard disciplines (e.g. engineering).

Yagiz and Demir (2015) argue that assertiveness among Anglophonic writers is due to their competencies of the language which they own. Zhu and Gocheco's study (2014) pointed out that American writers established a stronger writer-reader interaction with the use of these MD resources. Chinese's dominant use of hedges is due to the fact that, they are polite as influenced by the Confucian thought. This echoes Mohamed and Omer's (2000) assertion that the English have the propensity to be writer- responsible.

There is an obvious significant difference in the use of transitional markers in the articles between native and nonnative writers of English. The difference is due to the fact that, Persian writers using English language lacks the mastery of norms and conventions with regard to academic writing genres (Elahi & Badeleh, 2013) . In another study, Iranian journalists in their news articles about the 9/11 attack did not employ self-mentions and engagement markers. Iranian news articles on 9/11 behave conservatively due to the political and religious nature of the 9/11 event, thus, the propensity toward writer- responsibility (Yazdani, 2014). Lastly, their trainings inform them of the use of the third person pronoun, and the passive structure to do away with self-mentions.

Despite this vibrant contrastive enterprise, the scope has not been elaborated in other distinct genres. Books serve as an indispensable students' partner in their academic pursuit. There are many universities in the Philippines that require students of some main reference textbooks. In a book, there is a preface that is used by a writer to produce a highly effective preliminary statement or essay introducing its scope, intention, or background. Thus, it is expected that a book preface is deemed to be rhetorical which is likely to employ the categories of metadiscourse under study. It can be surmised that no study, to the knowledge of the authors, has deliberately explored the genre of a book preface. As Laurilla (2002) posits, there is more to contrast other than texts from the academic writing, thus this study.

There is a felt need to investigate this genre especially that many Filipino book writers and authors are blossoming in the advent of the newest K to 12 Curriculum. The results of this present study may be used by the curriculum writers and book authors in order to enhance the rhetorical moves they employ in their book prefaces. Publishing houses and policy makers especially in the curriculum division may also benefit from this study as they continue to educate many writers of the different rhetorical moves, preface in this study. Most especially, the study offers pedagogical concerns in an ESL classroom in order to educate the students of the metadiscourse features prevalent in this genre.

This paper aims at contrasting the presence of metadiscourse resources in the book prefaces of Filipino and English authors. It especially sought to see the similarities and differences of interactive and interactional resources between two groups of writers.

It is worth mentioning that the constructs of metadiscourse are found to be varied, but interrelated from one another. Although the first systematic attempt of metadiscourse was introduced by Vande Kopple (1985), his framework has been revised (Crismore et al., 1993; Hyland, 2005). From textual and interpersonal model by (Vande Kopple, 1985), Hyland and Tse use the terms interactive and interactional.

For the present study, it primarily adopts Hyland and Tse's (2004) model of academic metadiscourse, but also merges with other taxonomies by Crismore, Markkanen, and Steffensen (1993); Hyland (2007); Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik (1985); and Yagiz and Demir (2015). They serve as a framework and basis for identifying and classifying the similarities and differences as regards authors' use of interactive and interactional resources.

Table 1 shows a model of metadiscourse by Hyland and Tse (2004) and Hyland (2007) reflecting the interactive and interactional resources.

They refer to the way the writer manages the flow of information of the text (Thompson, 2001). The interactive resources include transitions, frame markers, endophoric markers, evidentials and code glosses. Transitions are mainly conjunctions used to mark addition, contrast, and consequential steps in the discourse. Frame markers are used to “sequence, to label text stages, to announce discourse goals, and to indicate topic shifts” (p. 168). Moreover, endophoric markers are some parts of the text referred to in order to make additional information. While evidentials indicate the source of information taken from outside sources, code glosses aid readers understand the functions of ideational material (Hyland & Tse, 2004).

Interactional refers to the way the writer explicitly intervenes by commenting on and evaluating the material (Thompson, 2001). In interactional resources, the writer involves the readers by providing them his or her perspective as regards both propositional information and readers themselves. These resources include hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions. While hedges project the writer's hesitance to present propositional information explicitly, boosters function otherwise, as they claim certainty and emphasis of the proposition. Attitude markers are used to express the writer's assessment of propositional information, that is, to convey surprise, obligation, agreement, importance, etc. Engagement markers, on the other hand, are used to involve the readers by addressing the readers through second person pronouns, imperatives, question forms, and asides. Lastly, self-mentions refer to the use of first person pronouns and possessives (Hyland & Tse, 2004) .

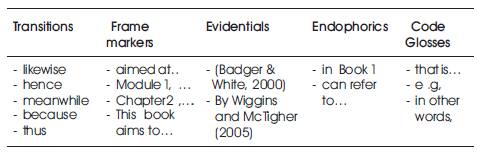

As regards interactive resources, they contain subcategories worth mentioning. For example, while evidentials take either in the form of integral or non-integral citation, endophoric markers take either linearly or nonlinearly. Lastly, code glosses have two types that include reformulation and exemplification. Reformulation can be in forms of expansions or reductions. Table 2 illustrates the sub-categories interative resources.

Also, the taxonomy of Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech & Svartvik (1985) was also used to classify the lexical items and phrases under boosters in the model of Hyland & Tse (2004) as presented in Table 3.

Lastly, another taxonomy was used in order to fully classify potential markers under two major MD resources as shown in Table 4.

The basis of this study was on book prefaces by 15 Filipino authors and 15 English authors, a mix of single and multiple authors: one author (7), two authors (7), and five authors (1) from the Filipino group; and one author (10), two authors (4), and three authors (1) from the English group. These sample representative texts from two different cultures were taken from the language area, that is, books on grammar, listening, speaking, reading, writing, and vocabulary between the years 2000 to 2015.

The Filipino prefaces represented five credible publishing houses in Metro Manila with a distribution of: House A (6), House B (5), House C (2), House D (1), and House E (1). On the other hand, the native corpora represented thirteen world-renowned publishing houses: House A (2), House B (2), House C (1), House D (1), House E (1), House F (1), House G (1), House H (1), House I (1), House J (1), House K (1), House L (1), and House M (1).

This unequal distribution is due to some dearth of language books in the Filipino counterparts. This does not affect the reliability of the results, since book prefaces do not reflect those of the company, but on the authors' rhetorical styles.

A small-scale study was intentionally done because there is a dearth of books concentrating on these language arts produced by Filipino authors. Majority of the books published in the Philippines are books for the basic education, covering at least eight major subjects in Mathematics, Science, Physical Education, Values Education, Technology and Home Economics, Philippine History, etc. The number of corpora would suffice in this initial study when compared to some international studies whose corpora ranged from 15-20 corpora for each group (Behnam & Mirzapour, 2012; Yazdani, 2014; Al-Qahtani, 2005, as cited in Alshahrani, 2015), and because of the dearth of language books, as aforementioned. Thus, the corpora from the language area qualify the methods of comparability (Kachru, 1999).

Almost all of the Filipino authors are known to have good reputation as book authors in the tertiary level. With regard to the English corpora, they were either American or British native writers of English. It is assumed, based on the some literature, that they share the same rhetorical pattern, described by Kaplan (1966) as linear.

All book prefaces from two groups of writers were encoded using Microsoft Word. After data collection, the corpora were analyzed using the following steps: identifying, classifying, and interpreting (Hyland & Tse, 2004) . To increase the validity of results, three raters who hold PhD in Applied Linguistics degree were asked to identify the words/phrases and their functions. They were given all the frameworks to be checked against the potential markers. All instances were examined based on the context in the text to ensure that, the identified words or phrases belonged to the exact category under study.

After all, the raters successfully extracted these features, a conference was held. This was to discuss some words or phrases with duplicity of functions, and to ensure that each specified lexical item or phrase actually behaved accordingly. A discussion was held to resolve cases of disagreement between and among inter-raters. Using Cronbach's Alpha, the inter-coder agreement reached high reliability.

Some studies on MD calculate the frequency of the features under study per 1,000 words. Due to the nature of the book preface, that is, the limited number of paragraphs, the researchers agreed not to employ this methodology. Instead, direct manual frequency counting was employed, which does not really affect the validity of the results (Yazdani, 2014).

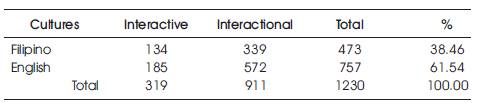

Table 5 represents the ranking of specific markers under interactive resources of both cultures. Book prefaces from the Filipino group of writers have a total MD hits of 134, while the English group of writers has a total hits of 185.

Table 5 shows a separate ranking of markers based on cultures. Obviously, there are only two markers out of five that are shared in ranking by both cultures, which include frame markers and transitions, ranked first and second, accordingly. The rest of the three specific markers failed to be identical to each other. As indicated in Filipino book prefaces, evidentials are ranked third, while evidentials are ranked fifth in the English group. While code glosses are ranked at the bottom from the Filipino group, code glosses are ranked second from the bottom from the English group.

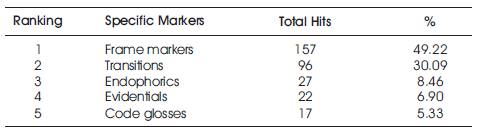

Table 6 shows the new ranking, when two cultures are combined as regards their interactive MD resources. Frame markers (49.22%) and transitions (30.09%) still topped the ranking with a total of 157, and 96 hits, respectively. The last three rankings are now claimed by endophorics (8.46%), evidentials (6.90%), and code glosses (5.33%).

Table 6. New Ranking in Interactive Resources Shared by Two Cultures

Data shows that, the two corpora mostly employ frame markers specifically the use of sequences and announcement of goals. This seems predictable as a book preface is a foreword that presents authors' or editors' organization of the book. Commonly used frame markers include: Chapter 1 presents.../ Part I discusses…/The aim of this book is to… etc. This is demonstrated in the book prefaces from two cultures, with a total hits of 54 from the Filipino group, and 103 from the English group. On the other hand, transitions come next in both cultures. The use of transitions is a mix of addition, contrast and consequential steps. As shown, there is a total hits of 50 from the Filipino group, and a total hits of 46 from the English group. As Behnam and Roohi (2012) posit, internal connections in the discourse are important features writers employ in order to make the reasoning unambiguous to the readers.

The performance of frame markers and transitions is consistent with other studies. For example, Alshahrani's (2015) study shows that, transitions and frame markers were the most commonly used interactive devices employed by the native writers of English and native writers of Arabic in the discussion and conclusion chapters in doctorate theses. Transitions also ranked first in the groups' persuasive essays of Malaysian students (Tan & Eng, 2014). Furthermore, Heng and Tan (2010) also found out that, frame markers topped second in the British Academic Written Essays (BAWE) corpus, and topped first in the Malaysian corpus of persuasive essays. Although a book preface is different from the introduction section of research articles, Zhu and Gocheco (2014) reported that “announcing goals” was the most frequently used subcategory of frame markers in both English and Chinese corpora.

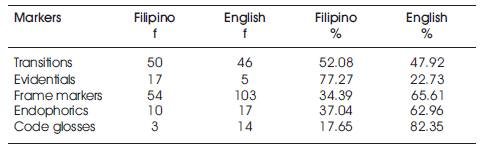

Table 7 shows the comparison between the specific markers under interactive resources when pitted against each other. As indicated, there are only two specific markers preferred by these representative Filipino authors that include: transitions and evidentials, while there are three specific markers more preferred by the English compared to their Filipino counterparts, which include: frame markers, endophorics, and code glosses. In totality, 3 out of 5 specific markers are dominated by the writers from the Inner Circle of English—the American and British book authors.

Table 7. Comparison between Two Cultures Per Interactive Markers

As indicated, Filipino representative authors used more transition markers than the English authors, although only slightly higher. Zhu and Gocheco (2014) mention that, a progressive style in research articles of applied linguistics among Chinese writers, mostly on addition, is capable of building the argumentation. Chinese writers belong to the Expanding Circle of English which is also true among Filipino book authors who belong to the Outer Circle of English. In other cross-cultural studies, transitions were more frequent in the Chinese research articles than in the English corpus (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014). Transition markers were also preferred by the Arabic writers of research abstracts, mostly the additive type when they were compared with the English writers' articles in applied linguistics (Alotaibi, 2015). Even in the field of computer sciences, transitions were the most frequent used markers (Behnam & Roohi, 2012) .

Meanwhile, English writers use more frame markers, endophorics, and code glosses. In terms of frame markers, other studies show conflicting results although they are predictable because a book preface is a distinct genre. For example, frame markers were less frequent in the English research articles than in Chinese corpus (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014), while English writers prefer the use of frame markers in the interactive resources (Alotaibi, 2015).

One interesting result is worthy of consideration when Filipino authors use evidentials (77.27%) twice higher than the English writers (22.73%). It may be a fact that, Filipino authors have not established their own credibility as writers, so to speak. The use of integral citation and non-integral citation (Table 8) is but common in academic writing in the Philippines. First, Filipinos are toyed with the idea of self-respect by respecting other's intellectual properties. Taking ideas and work of others without giving them full credit is an unprofessional act. Second, there is a strong abhorrence of plagiarism in the academic writing that is even inculcated among students in the basic education arm in the Philippine system. Professional writers are not an exemption to this practice. Third, Filipino writers/authors are still influenced by Western thoughts. Citing evidence from Western authorities is an important feature in one's written output. Hyland (2005) maintains that citation is central to persuasion that provides justification for arguments being presented.

Table 8. Sample Markers under each Interactive Resource Employed by both Cultures

On the contrary, English authors use evidentials infrequently. Results imply that, writers in the inner circle of English act and project an image of authority. Their credibility as writers and authors have been deeply established especially that half of the books were published by world-renowned University publishing houses. Thus, citing other authors by employing an integral and non-integral style becomes trivial in their part. Their expectation is that they are the ones to be cited, not the other way around. On the contrary, these authors may be toyed with the idea that, a book preface is a distinct genre, and they see no reason to use many citations. However, a study by Zhu and Gocheco (2014) debunks this claim when they found out that, there was a prevalent use of citation in the English text which implies that English writers of research articles seemed to use contextualization and justification in their texts.

Although, a book preface is different from research articles. Lastly, Table 9 shows in what culture are interactive resources more prevalent in the sample book prefaces. It is clear that, the English book authors employ more interactive MD resources such as frame markers, transitions, endophorics, evidentials, and code glosses when compared to their Filipino counterparts of book authors. In textual metadiscourse, the writer guides the readers by his or her explicit style of textual organization, and informs them of his preferred interpretations. This does not echo to the findings of Alotaibi (2015) when it is found out that the Arabic writers used more interactive metadiscourse markers compared to their English counterparts in their Research Articles (Alotaibi, 2015).

Table 9. Performance of Interactive Resources according to Culture

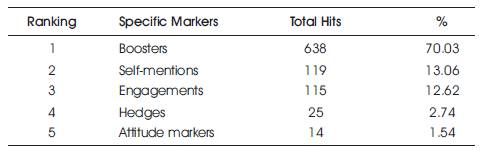

Table 10 presents the ranking of specific markers under interactional resources of both cultures. Book prefaces from the Filipino group of writers have a total MD hits of 339, while the English group of writers has a total hits of 572.

Table 10 shows a separate ranking of markers based on cultures. Results show a consistent order of specific markers in both cultures. Boosters tops the ranking which is much higher compared to the other types of markers. Self mentions, engagement markers, hedges, and attitude markers followed the ranking.

Table 11 shows the new ranking of specific markers when two cultures are combined as regards their use of Interactional Resources. The same ranking is still found because as cited in Table 10, both cultures share the same ranking. Boosters top the ranking in both cultures with a total hits of 638, equivalent to 70.03%. The last four markers are self-mentions (13.06%), engagements (12.62%), hedges (2.74%), and attitude markers (1.54%).

Table 11. New Ranking in Interactional Resources Shared by Two Cultures

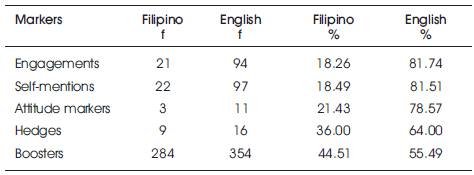

Table 12 shows the comparison between the specific markers under interactional resources when pitted against each other. Results clearly show that, English authors claim all specific markers, considered much higher than their Filipino counterparts. Specifically, the ranking claimed by the English writers include: engagements, self-mentions, attitude markers, hedges, and boosters. The same table also shows that, aside from employing fewer interactional resources, Filipino authors employ higher cases of hedges (36.00%) but at the same time close to using boosters (44.51%) when treated individually

Table 12. Comparison Between Two Cultures Per Interactional Markers

The English use of more markers in interactional resources corroborates other findings although previous studies zeroed in on different genres. For example, hedges were the most frequently used resources by the American Journalists in their news Articles about the 9/11 attack (Yazdani, 2014). The use of hedges “reflects the critical importance of distinguishing fact from opinion in academic writings and the need for writers to evaluate their assertions in ways which recognize potential alternative viewpoints” (Behnam & Roohi, 2012, p. 31). Also, English writers were more cautious by using more hedges, more certain by using boosters, and more expressive by using attitude markers compared to their Arabic counterparts (Alotaibi, 2015). Hyland (2005) maintains that, hedges welcome negotiation, and that, the English behave cautiously and tentatively, resorting them to use more hedges (Hyland, 2005), giving the audience a tentative stance.

In some other genres, native writers of English used self-mention more frequently than the Arab writers in their Research Articles (Sultan, 2011). They also employed more hedges in their academic essays when compared to the Arab students (Btoosh & Taweel, 2011). Also, Yagiz and Demir (2015) found out that, the Anglophonic authors used adverbial boosters at the highest scale in their research articles. Moreover, self-mentions from the English group got the highest total hits of 97 compared to 22 from Filipino authors. Self-mention is very low in persuasive essays among British students, and the same time very low in the Malaysian corpus (Heng & Tan, 2010). However, the use of MD resources heavily relies on the type of genre it belongs.

The profuse use of self-mentions by the English authors echoes repetitive literature review on the individualistic nature of the Western Countries like the USA and the United Kingdom (Mohamed & Omer, 2000). For the English authors, personal accolade matters to them compared to some Filipinos whose humility is obviously seen. Zhu and Gocheco (2014) maintain that, English writers used higher self-mention compared to their Chinese equivalents, nearly twice as much as Chinese writers. English writers must be toyed with the importance of personal and social identity as they proudly announce their contributions in their respective fields. Just like Filipino authors in this study, Chinese writers were seen to be reluctant to use selfmention devices. This shows their humility by hiding their authority—a trait influenced by the Confucian Thought (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014).

When treated individually, Filipinos' most frequently used interactional resources are the use of boosters. However, when pitted against the Inner Circle of English, it is found that the English authors employ a slightly higher use of boosting mechanisms. This comparison is quite predictable since a book preface “sells” to the readers what the book can offer to them. Consequently, they resort to using different words to sound much more convincing. As Behnam and Mirzapour (2012) revealed, intensity markers are common in applied linguistics in their research articles. Boosters are intensity markers (Yagiz & Demir, 2015) that have to do with the assertiveness of the writers to enhance their propositions. Yagiz and Demir continue that, Turkish writers are known to be culturally less assertive compared to their Anglophonic and Japanese counterparts. This is also the case of Filipino authors when they are compared to these English authors.

Needless to say, some other resources such as attitude markers and engagements have their own places in the book prefaces. Engagement is how authors include the readers in their propositions. In the BAWE corpus, Heng and Tan (2010) share their findings that engagement was the least employed by the native writers of English, but it topped the ranking in the Malaysian corpus of persuasive essays. Also, engagement markers were least frequently used resources by the American Journalists in their news articles (Yazdani, 2014). On the other hand, attitude markers were the most frequent markers used by the Persian news articles about the 9/11 attack (Yazdani, 2014), but with a minimal use in attitude markers in the field of computer sciences (Behnam & Roohi, 2012). Lastly, both English and Chinese writers appeared not to involve their affective attitude towards the preposition (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014).

Lastly, Table 13 shows in what culture are interactive resources more prevalent in the sample book prefaces. English authors remain consistent in the number of use across five specific markers under interactional resources, considered twice higher than their Filipino counterparts. Metadiscourse provides us with strong idea of how academic writers involve their readers through their convincing propositions and coherent texts (Hyland & Tse, 2004). The table demonstrates that the American writers are more interactional than the Filipino authors.

Table 13. Performance of Interactional Resources According to Culture

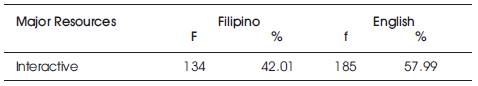

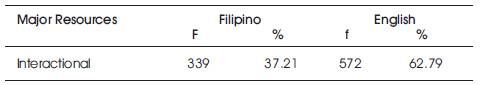

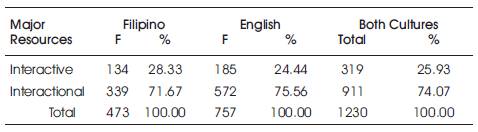

Table 14 presents the overall performance of MD resources when two cultures are combined.

Table 14. Performance of Both Cultures According to Metadiscourse Resources

As a whole, both cultures employ the use of interactional MD resources, twice higher than the interactive MD resources. This is the case of other genres under study. In the study of Malaysian persuasive essays, they employed a bigger preference of interactional over interactive resources (Tan & Eng, 2014). The Malaysian corpora employed more on the interactional resources than with the interactive MD resources in their essays (Heng & Tan, 2010). Most importantly, American Journalists used more interactional metadiscourse features in their news articles compared to their Iranian equivalents (Yazdani, 2014) .

On the contrary, there are cases of preference of interactive over interactional. According to Zarei and Mansoori (2011), the applied linguistics group that represented the humanities zeroed in on textuality, compromising the reader involvement in written texts. Other studies on different genres supported accordingly. Both English and Arabic writers of research abstracts used more interactive than interactional markers (Alotaibi, 2015). In summary, interactional resources are much higher than interactive resources when applied in a book preface.

Arguably, metadiscoursal comments have two main functions, that is, textual and interpersonal. The textual function points out topic shifts, signal sequences, cross referencing, connect ideas, and preview the materials, while interpersonal function is observed with the use of hedges, booster, self-reference, evaluation (Hunston & Thompson, 2001) and appraisal (Martin, 2001). This accounts for reader's knowledge, textual experiences, and processing needs. While the former organizes the discourse, the latter is capable of modifying and highlighting the aspects of the texts, including the writer's attitude (Hyland & Tse, 2004). In this study, book authors adhere to the idea that a book preface is where they can build good rapport and real connection with the interested readers. As Hyland and Tse (2004) posit, writers have to anticipate the needs of the readers in order to let them involved with the text.

Metadiscourse takes account not only the reader's knowledge but also his or her textual experiences and processing needs. Interactive refers to the way the writer manages the flow of information of the text (Thompson, 2001). Interpersonal metadiscourse is the expression of one's personalities embodied in the text. This characterizes the kind of writer-reader interaction that is intended to take place (Hyland & Tse (2004). The findings of this study show that, interactional resources are more important than interactive resources for a book preface.

Table 15. Performance of Metadiscourse Resources by Culture

As shown in Table 15, as regards cultural differences, English authors use more MD resources twice as the Filipino authors. This means that, the English authors are preoccupied with two major MD resources in their book prefaces, that is, they are concerned in the textual organization, and the same time establishing writer-reader relationship. Citing some related studies, the use of textual and interpersonal metadiscourse markers in dissertations was more prevalent among the native English writers than that of the Iranian writers (Behnam & Roohi, 2012) . English research articles employed more metadiscourse features than the Chinese research articles (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014), but as a whole, both English and Chinese writers employed more interactive resources than the interactional resources in their research article introductions (Zhu & Gocheco, 2014).

However, it worth mentioning that, more paragraphs are observed in the English corpora. The English authors tend to be verbose and elaborate while Filipinos are seen to be economical and straightforward, maintaining the sense of humility among them. Future studies should address this loophole before arriving at the generalizations.

The study, for the first time, investigated the similarities and differences of interactive and interactional MD resources in the book prefaces among Filipino and English writers on language books published between 2000-2015. It also looked into the similarities and differences within the subcategories of interactive resources.

When grouped individually, frame markers and transitions are frequently used by Filipino authors. Code glosses are the least employed interactive resources. When grouped individually, frame markers and transitions are frequently used by English authors. Evidentials are the least employed interactive resources. Furthermore, when shared by two cultures, frame markers and transitions top the ranking among other interactive resources such as endophorics, evidentials, and code glosses. After specific markers are pitted against each other, there are only two specific markers preferred by the representative Filipino authors that include: transitions and evidentials, while there are three specific markers more preferred by the English compared to their Filipino counterparts, which include: frame markers, endophorics, and code glosses.

Likewise, Filipino authors use evidentials twice higher than the English writers which implies that, Filipino authors have not established their own credibility as writers, so to speak. They are also toyed with the idea of respect of intellectual property, abhorrence of plagiarism, and influence from the Western thought as a model of educational theories and practices. English authors use evidentials infrequently, which projects an image of authority. The limited use of evidentials may also explain that, a book preface may not need so much integral and non-integral citations. In short, the interactive resources are more prevalent in the English corpora.

When grouped individually, boosters and self mentions are frequently used by both Filipino and English authors. They are followed by engagement, hedges, and attitude markers. When specific markers are pitted against each other, the ranking is still the same: boosters, self mentions, engagements, hedges, and attitude markers. English authors claim all specific markers, considered much higher than their Filipino counterparts.

The profuse use of self-mentions by the English affirms the individualistic nature of the Western countries. Humility with fewer hits of self mentions is an act of humility among Filipino authors. Attitude markers are used moderately by both cultures. Furthermore, the use of more engagement among English authors is influenced by the use of more interactional resources. Lastly, the interactional resources are more prevalent in the English corpora.

Both cultures employ more interactional MD resources, twice higher than the interactive MD resources. While the interactive MD resources organize the discourse, the interactional resources modify and highlight the aspects of the texts, including the writer's attitude (Hyland & Tse, 2004). The findings of this study show that, interactional resources are more important than interactive resources for a book preface. A book preface that is intended for the interested and expected audience needs to be more interactional than interactive.

English authors use more MD resources twice as the Filipino authors. It may imply that, Filipino authors need to be more sophisticated in their foreword of their books. As seen, Filipinos are economical, that is, with limited number of paragraphs in their prefaces. In a nutshell, the differences are due to some cultural orientations of humility vs. self-accolade.

Although the study is considered small-scale, the results may initially confirm that, the employment of some metadiscourse markers is heavily regulated by two important factors: the culture and writing conventions that a genre belongs. Genres in writing are produced based on their communicative purposes, plus the conventions of the discourse community that the genre is intended for, thus the expected differences on rhetorical patterns and writer-reader connection. In short, the production of distinct written genres is purely discipline-based and discourse community-based.

The results have provided initial but germane insights as regards this distinct genre. The results put forth that, indeed, differences in interactive and interpersonal resources reside in the texts whether intentional or unintentionally positioned by the writers. Further studies need to investigate whether the use of these metadiscourse resources were produced consciously or not. This can help further analyze how they calibrate this genre as a way of establishing audience rapport and connection. A book preface is the part where they “sell” their books to the expected audiences.

This present study has a number of caveats to consider for the future studies. First, the corpora were not uniform in terms of the distribution of the publishing houses they were published, and the uniformity of the number of authors per culture. Second is the number of corpus from each group. Future studies of a large corpus is imperative in order to subject the results to Chi-square. This helps us see the significant differences of the metadiscourse categories employed by the groups of writers. A larger corpus is also needed in order to avoid a hazy generalization as regards the MD resources presented in the results. It is hoped that, future studies address the limitations of the study aforementioned in order to provide much more reliable results.

It might also look plausible if teachers introduce MD to the students. Recent studies point out an improved reading comprehension among students (Tavakoli, 2010), and improved speaking abilities of the students (Ahour & Maleki, 2014) when MD was explicitly taught. It is time the teachers incorporated the rhetorical domains of texts and speech in order to help students become more conscious of the communication processes.