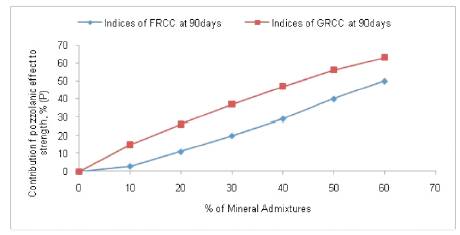

In the present paper the pozzolanic effect of two different mineral admixtures( Fly ash and Ground granulated Blast Furnace slag) in Roller compacted concrete (RCC) was studied quantitatively with various strength indices namely specific strength ratio(R), index of specific strength(K) and contribution rate of pozzolanic effect to strength(P). Cement was partially replaced with mineral admixtures by 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% and 60% by weight respectively for Fly ash (FA) and Ground granulated Blast Furnace slag (GGBS). Besides the strength properties, these indices showed that early curing age, specific strength of Fly ash Roller Compacted Concrete (FRCC) decreases with increase in FA content, whereas the specific strength of GGBS Roller Compacted Concrete (GRCC) increases with increase in GGBS content. After 90 days of Curing, the contribution of mineral admixture effect on Flexural Strength of FRCC and GRCC are 50% and 63 % respectively.

The American Concrete Institute (ACI) defines roller compacted concrete (RCC) as the concrete compacted by roller compaction [1]. RCC is a stiff and extremely dry concrete and has a consistency of wet granular material or wet moist soil. The use of RCC as paving material was developed from the use of soil cement as base material. The first use of RCC pavement was in the construction of Runway at Yakima, WA in 1942 [2]. The main advantage of RCC over conventional concrete pavement is speed in construction and cost savings. RCC needs no formwork, dowels and no finishing [3].

In the construction of RCC pavement, adding the active mineral admixtures like GGBS and Fly ash has great scientific advantages. FA generally consists of Silica (SiO2) and Alumina (Al2O3) and has potential activity. The useful effects of FA can be of three folds; Morphologic, pozzolanic and micro aggregate effects. The pozzolanic effect of FA is that it combines oxides of Silica (SiO2) and Alumina (Al2O3) in FA, activated by Calcium Hydroxide (i.e. the production of cement hydration) and is producing more hydrated silicate gel. This gel is contributing more to the strength at later ages [4].

Xincheng Pu [4] stated that the concrete strength consists of two main folds; one came from the chemical reaction between cement and water and second from the pozzolanic effect of mineral admixture. But the pozzolanic effect of FA is mainly contributed towards the long-term strength. Cheng Cao et al [5] investigated the high volume fly ash effect on the RCC and showed that the FA effect at early ages of curing is negative with an increase in FA content. But the pozzolanic effect of FA on RCC at longer ages (90 days) becomes more significant and remarkable.

M. Madh Khan et al [6] investigated the addition of pozzolana on the strength of RCC. With increase in pozzolana, the 28 days compressive strength values were decreased, although the 90 days compressive strength was increased with pozzolana and rupture modulus was decreased. Ali Mardani [7] concluded that with the increase in FA content in RCC, the strength values were decreased. At later ages of curing the rate of strength development of mixtures with FA were very close and independent of the fly ash content of the mix.

Granulated Slag is produced in blast furnaces as a byproduct of iron manufacturing industry. It is derived from minerals of iron ore and foundry coke and flux ashes. GGBS essentially consists of Calcium; Aluminum silicates are the requirements of good hydraulic binder. Due to the hydration of cement and water, calcium silicate gel(C-S-H) and calcium hydroxide crystal [Ca (OH)2] are formed in large amounts. The [Ca(OH)2] formed has the negative effect of decreasing the quality of concrete. So this unintentional product can be converted into useful product by the addition of GGBS and at the end of the reaction of slag with [Ca(OH)2], the calcium silicate gel is being formed which contributes to the addition of strength [11-13].

K. Ganesh Babu et al [8] studied the efficiency of GGBS in concrete at various replacement levels up to 80% by weight of cement. The strength efficiency was a combination of general efficiency factor and percentage efficiency factor (depends on % replacement of GGBS). A. Oner and S. Ayuz [9] studied the optimum usage of GGBS in concrete by adding GGBS in an amount equivalent to 0%, 15%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90% and 110% of Cement content. They proved that compressive strength of concrete with GGBS increases as the amount of GGBs increase up to an optimum level of 55% of the total cementitious content, Beyond this optimum content the addition of GGBS does not improve the compressive strength, due to the UN reacted GGBS, acting as a filler material in the paste.

The Pozzolanic and cemenitious behavior of GGBS is similar to that of the high calcium FA. Hogan et al [10] found that at 40%, 50% or 65% cement replacement with slag by weight, the strength contribution up to 3 days of curing was low in mortars.

Extensive research has been conducted on the use of FA in RCC. But there is little research work done on the pozzolanic effect of GGBS in RCC. Therefore this research is intended to investigate the pozzolanic effect of GGBS on RCC and to compare the strength indices of Fly Ash Roller Compacted Concrete (FRCC) and GGBS Roller Compacted Concrete (GRCC) quantitatively. GGBS has become an essential mineral admixture for producing good pavement quality concrete and the same can be used in the design and construction of low volume rural roads. The findings of this experimental investigation will be useful in predicting the behavior of RCC made with GGBS intended for lean concrete bases and cement concrete surface courses and similar applications.

1. To Proportionate the RCC material for a specified flexural strength( 5MPa)

2. To investigate the pozzolanic effect of FA and GGBS in RCC

3. To compare the strength indices of FRCC and GRCC at various replacement levels of mineral admixture (10%, 20%,30%,40%,50% and 60%)

It is defined as the contribution of 1% cement to Roller Compacted Concrete strength which can be calculated as

Where, F is the Strength of Roller Compacted Concrete,

P is percent of cement to total amount of Binder

It is the contribution of mineral admixture to the strength of concrete with mineral admixture and it can be formulated as

Where,

SPMRCC = Specific Strength of RCC with Mineral admixture

Ratio of concrete strength in question to cement or mineral admixture percentage, given by the following expression,

Where,

F= RCC strength, p is percentage of cementitious material

Where,

RM is the contribution of unit mineral admixture to RCC strength.

RC is the contribution of unit cement to RCC strength without any mineral admixture.

It is the ratio of RM to RC and is given by the following expression,

It is given by the expression,

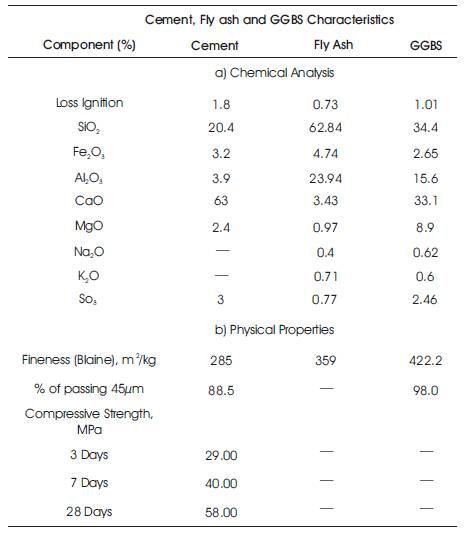

Ordinary Portland Cement OPC 53 Grade (Figure 4) was used in the present experimental investigation. Physical Properties of cement is shown in Table 1. Cement was tested as IS 4031 [15].

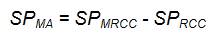

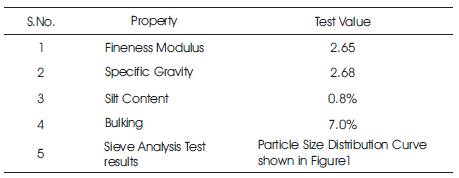

2.1.2 Fine AggregateRiver Sand was used as fine aggregate in all concrete mixes used in the experimental work. This aggregate was air dried and then cleaned to remove organic matter from it. The properties of fine aggregate is shown in Table 2. It was conforming to IS: 383-1970[16] requirements. Particle Size Distribution Curve for Fine Aggregate is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Particle Size Distribution Curve for Fine Aggregate

Figure 2. Particle Size Distribution Curve for Coarse Aggregate

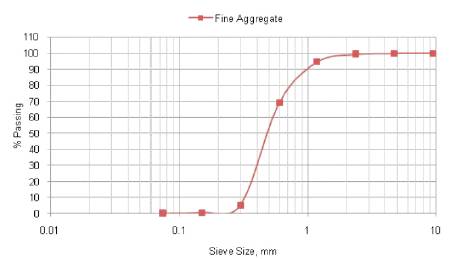

Figure 3. Particle Size Distribution Curve for Combined Aggregate

Figure 4. Cement, Fly Ash and GGBS

Table 1. Properties of Cement, Fly ash, GGBS

Table 2. Properties of fine aggregate

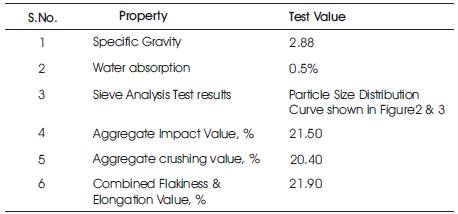

An igneous rock material consisting of granite was used as coarse aggregate in the Proportion of RCC. The grain Size distribution and other properties are shown in Table 3. The gradational requirements of combined aggregate were as per ACI 211.3R-02 [18]. Particle Size Distribution Curve for Coarse Aggregate and Combined Aggregate are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

2.1.4 WaterThe water used in RCC mix design was potable and drinking water.

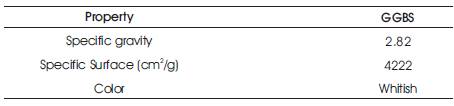

2.1.5 Ground Granulated Blast furnace Slag (GGBS)The GGBS used in this research project was collected from a Private Limited Company located at Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh, India. The GGBS was ground in a laboratory mill to a Blaine fineness of 4222 cm2/g. The Physical properties of GGBS is shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Properties of Coarse aggregate

Table 4. Physical Properties of GGBS

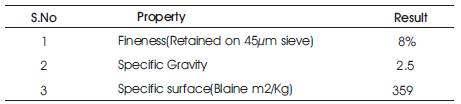

Fly ash was obtained from Narla TataRao Thermal Power Station(NTTPS) at Ibrahimpatnam, Vijayawada, India. It was tested as per IS 1727:1967 [17] and the results of tests is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Physical Properties of Fly ash

Mix proportioning of RCCP was done using ACI 211 3R-02- 2004 [18] method. This method was developed for Roller compacted concrete pavements of Rigid pavement category and it is limited to mix design with the nominal maximum size of aggregate of 19mm as per ACI 325.10R- 99[2]. The RCCP mix was proportioned for specified target flexural strengths of 5.0N/mm2 [19- 25]. The cement content 3 of control mix of RCC was 295kg/m3 . In six RCCP mixtures 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60% weight of cement were replaced with mineral admixtures (GGBS and Fly Ash). The identification of mix proportions and quantity of material are shown in Table 6.

Beam specimens of size 500x100x100 mm were used for measuring flexural strength in beam moulds and compacted with modified proctor's rammer. They were demoulded and kept for curing after one day. Then Flexural strength test was conducted on the UTM of capacity 1000 KN by third point loading at 3,7,28 and 90 days [26] . Figure 5 shows the Flexure test on FRCC and GRCC. The test results are shown in Table 6.

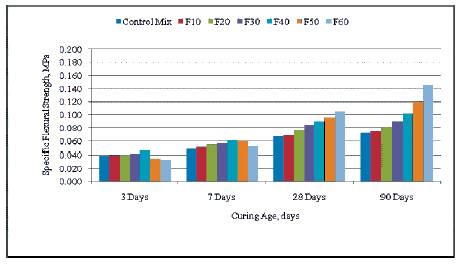

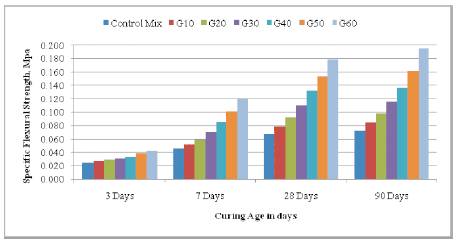

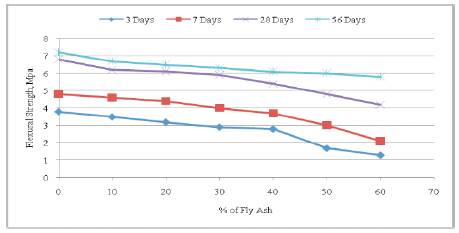

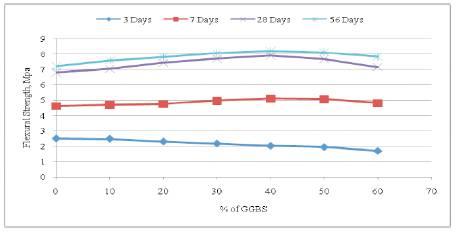

The development of flexural strength of FRCC & GRCC with curing age are shown in Figure 6 and 7. In the early ages of 3 days, with the increase in fly ash content, RCC decreases at all levels of replacement. When it is cured for more than 28 days, the contribution of fly ash to flexural strength in FRCC is significant. Where as in GRCC, with an increase in percentage of GGBS RCC also increase at all ages of curing up to 90 days.

Figure 6. Flexural Specific Strength of FRCC with Curing Age

Figure 7. Flexural Specific Strength of GRCC with Curing Age

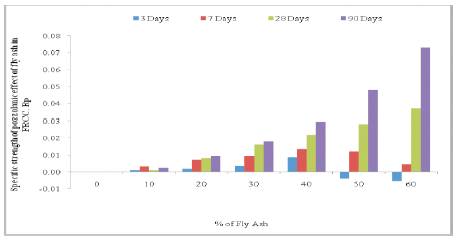

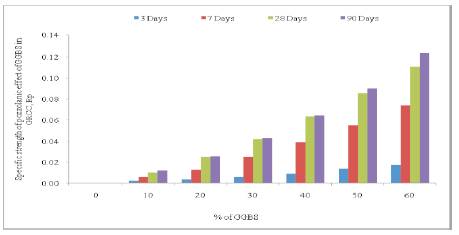

Figures 8 & 9 show the trend of Flexural Specific Strength of pozzolanic effect of (SPFA) mineral Admixture in FRCC and GRCC. At initial ages of 3 days and 7 days, the pozzolanic effect of fly ash is very low or negative (at 3 days for all mixes and at 7 days for R60), but it is increasing very rapidly at 90 days with an increase in fly ash content. In the long term curing age, fly ash even at 60 % replacement level provides an effective contribution to strength. In Figure 9, the pozzolanic effect of GGBS is low at 3days for all levels of replacements. But with the increase in age of curing the specific strength of pozzolanic effect increases at slow rate up to 7days and at rapid rate beyond 28days of curing.

Figure 8. Flexural Specific Strength of pozzolanic effect of Fly ash

Figure 9. Flexural Specific Strength of pozzolanic effect of GGBS

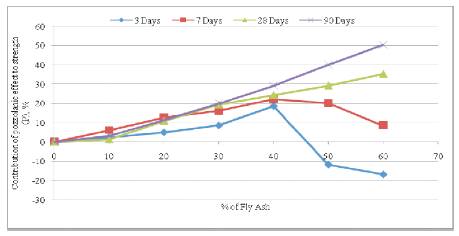

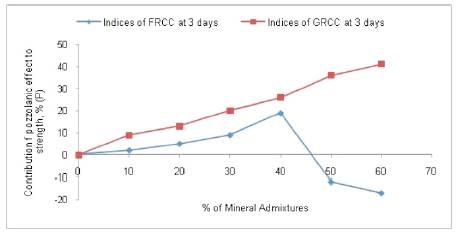

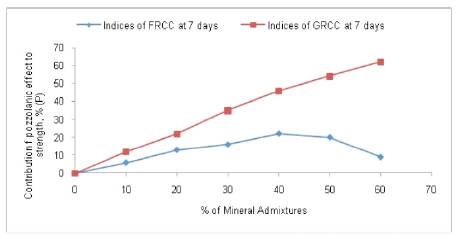

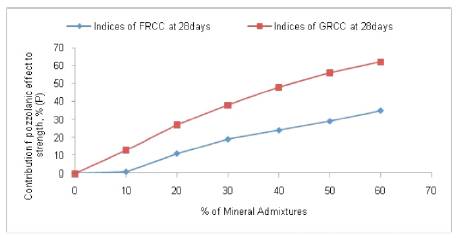

The pozzolanic indices for flexural strength for FRCC and GRCC were calculated and shown in Tables 8-10. Table 7 shows that the indices of pozzolanic effect (RP and P) of flexural strength at 3 days of curing age are showing negative values, when fly ash content is more than 50%. But in Table 10, these indices are showing improved values with an increase in fly ash content at 28 days and 90 days of curing. However, in GRCC these indices are showing positive and increased values at all ages with increased levels of GGBS.

From Tables 8-11 and also from Figures 5, 10, 11, 12, 13, it is clear that the flexural strength of FRCC and GRCC and indices of pozzolanic effect is increased with curing age. During the early period of curing at 3 days, the pozzolanic effect of fly ash is minimum. As the curing age increases, the contribution rate of pozzolanic effect of fly ash also increases. This implies that curing age is an important factor in the pozzolanic effect of Fly ash for RCC.

Figure 10. Change in Flexural Strength versus percent of fly ash in the Mix

Figure 11. Variation of P with fly ash content in RCC (Compressive Strength)

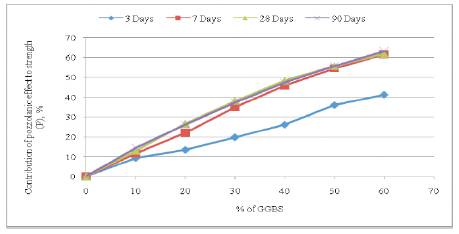

Figure 12. Change in Flexural strength versus percent of GGBS in the Mix

Figure 13. Variation of P with GGBS content in RCC (Flexural Strength)

From Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, it is seen that at early ages of curing, P has a tendency to decrease with the increase in Fly ash content in the FRCC. At 3days of curing age, the fly ash effect in FRCC with replacement levels of 50% and 60% shows negative values, which indicates that there is no significant contribution to flexural strength, and this is due to the fact that fly ash delays the hydration action of cement in the FRCC. But at the ages of 28days and beyond, the growth rate of 'P' increases with the increase in fly ash content and increase in age. At 90 days of curing age, the contribution of pozzolanic effect is significant and remarkable.

From Figures 10, 11, 12, 13 and from Tables 8, 9, 10, 11 it is seen that at all ages of curing, P has a tendency to increase with increase in GGBS content in GRCC. At early ages of curing i.e. 3days, P has a significant value of 41%. However, at the ages of 7days, 28days and 90days, the contribution of the pozzolanic effect in GRCC is remarkable and significant. A comparative variation of ‘P’ is shown in Figures 14, 15, 16, 17.

Figure 14. Variation of P with GGBS content in RCC (Flexural Strength) at 3 days

Figure 15. Variation of P with GGBS content in RCC (Flexural Strength) at 7 days

Figure 16. Variation of P with GGBS content in RCC (Flexural Strength) at 28 days

Figure 17. Variation of P with GGBS content in RCC (Flexural Strength) at 90 days

The pozzolanic effect of the Mineral Admixtures(Fly ash & GGBS) in Roller Compacted Concrete Pavement was quantitatively examined through various strength indices like Specific Strength Ratio (R), Index of Specific Strength (K) and Contribution percentage of pozzolanic effect to Strength (P). This experimental work shows the following conclusions:

1. With the increase in Fly ash content in FRCC the flexural strength decreases. Although the strength is very low at early curing aging of 3 days and 7 days, it develops rapidly with increase in curing aging. The strength at longer ages will be exceeding with that of the control concrete mix without fly ash.

2. Fly ash effect in FRCC is positive after 28 days of curing aging. The Contribution of fly ash in FRCC with 90 days curing age to Strength exceeds 50 %, and is most remarkable and significant in this age.

3.With the increase in GGBS content in GRCC, the flexural strength decreases at the ages of 3days and 7days, but at the age of 28days, the strength is more than control mix even at 60% replacement level.

4.The specific strength of FRCC decreases with increase in fly ash content at early ages curing. Whereas the specific strength of GRCC increases with increase in GGBS content at all ages.

5. The fly ash effect in FRCC is positive only after 28days at all replacement levels. Whereas the GGBS effect in GRCC is positive for all ages (3Days, 7Days, 28Days, and 90Days) and at all replacement levels (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% and 60%).

6. The contribution of fly ash in FRCC at 90days of curing to flexural strength at 60% replacement level, exceeds 50%, whereas the contribution of GGBS at the same age is 63% and is more remarkable.