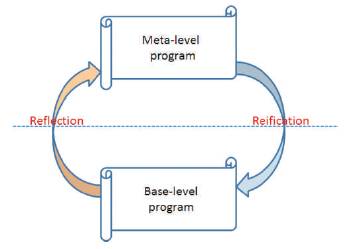

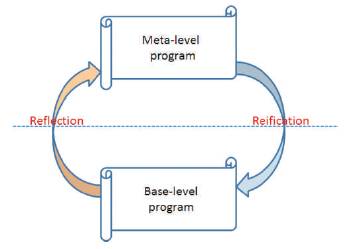

Figure 1. The structure of a reflective system

Computational Reflection has shown much promise for improving the quality of software by providing programming language techniques to address issues of modularity, reusability, maintainability, and extensibility. The Meta-Object Protocol (MOP) is a powerful tool to provide the capability of computational reflection by means of object oriented and reflective techniques to organize a meta-level architecture. It provides a set of interfaces for developers to access the underlying implementation of programs in order to automate the source- to-source program translations. In this paper, the author describes how to bring the power of computational reflection to C through a MOP, named OpenC, which offers a framework to build arbitrary source-to-source program transformation libraries for large software systems written in C. The design focus of OpenC is to automate program transformations in a straightforward and transparent way through techniques of code generation, so that client users only need to add a simple annotation to their code to be manipulated, while removing the need to know the details on how the transformations are performed. The paper provides a general motivation for using reflection and explains briefly the design and implementation of the OpenC framework. In addition, this paper will show an example, how OpenC can be used to build a simple profiling library that can be employed to analyse the distribution of execution time among all functions in a project by recording the amount of time spent on executing each function.

Reflection has a deep history in areas such as logic and philosophy [2]. The concept of computational reflection was introduced within the context of computer science by Brian Smith as a way to extend the semantics of programming languages [1]. According to Smith, a reflective system is able to reason about and manipulate itself based on an explicit and principled means of representing its implementation [1].

Maes [3] presented a formal definition of computational reflection as “a computational system which is about itself in a causally connected way.” To further elaborate on this concept, Maes discussed several relevant concepts regarding computational reflection [3]:

Usually a reflective system includes a base-level part and a meta-level part which are shown in Figure 1. The baselevel part is responsible for dealing with problems and returning computational results of its domain (this is the typical program written by programmers), and the metalevel part addresses problems and returns information about the base-level [3].

Concerning the manipulation power of a reflective system, reflection can be categorized as introspection and intercession [4]. Introspection is the ability of a system to inspect and answer questions about the structure and state of its own execution, while intercession also allows the internal structure of its execution to be altered. To achieve this, both the static structure and the running state of a reflective system must be represented as data. The process of such representation is called reification.

Reflection can also be distinguished as structural reflection and behavioral reflection based on the dimension that the objects of the meta-level program operate. Structural reflection is about the manipulation of the static structure of a program. With structural reflection, the definition of data structures, such as classes and methods can be retrieved and even modified (e.g., getting a list of all public methods available for a class, or adding a new method). Behavioral reflection focuses on the semantics of an executing system and provides a complete reification of both the semantics of the language and the execution states [5]. Behavioral reflection makes it possible to intercept and alter operations during run-time (e.g., field access, and method invocation). It is easier to implement structural reflection and many modern languages have already integrated this feature. On the contrary, it is more challenging to realize complete behavioral reflection mostly because to incorporate behavioral properties without adversely affecting the performance is especially difficult.

Figure 1. The structure of a reflective system

Computational reflection, in the realm of programming languages, refers to the paradigm that provides programming languages with the power to extend the semantics by representing and modifying a program in the same way that a program represents and modifies the data that it processes[1]. The Meta-Object Protocol (MOP) has been proven to be a powerful tool to provide the ability of computational reflection to a program by means of object-oriented and reflective techniques to organize a meta-level architecture [13].

A meta-object protocol is an interpreter which enables extending or redefining the semantics of a program to make it open and extensible, by providing a set of interfaces to access the program’s underlying implementation[7]. To allow transformation from a metalevel, there must be a clear representation for the base program of its internal structure and entities (e.g., the classes and methods defined within an object-oriented program) and well-defined interfaces through which these entities and their relations can be manipulated [3]. Through the interfaces, client programmers can incrementally change the implementation and the behavior of the program to better suit their needs.

In a MOP, each entity in the base program is represented with a meta-object in the meta-level program. The class from which the meta-object is instantiated is called the meta-class. For instance, for a function defined in C programming language, a corresponding meta-object will be constructed in the meta-level program. The metaobject for the function holds adequate information to describe the structure and behavior of the function and interfaces carefully designed to alter them. Through a MOP, an entity that is not a first-class citizen in the baselevel program now becomes a first-class citizen that can be constructed, passed as a parameter to a function and returned or assigned to a variable [14]. The interfaces may be manifested as a set of classes or methods so that users can create variants of the default language implementation incrementally by sub-classing, specialization, or method combination [8]. For example, in OpenC++ [9], end-users are allowed to define metaclasses specializing in certain types of transformation by sub-classing standard built-in meta-classes. In a MOP implemented in a class-based object-oriented language, the interfaces are supposed to include at least the basic functionality of instantiating a class, accessing attributes and invoking methods.

Based on the time when the meta-objects exist, a MOP may be run-time or compile-time. Run-time MOPs function while a program is executing and can be used to perform real-time adaptation, e.g. the Common Lisp Object System (CLOS) [8] that allows the mechanisms of inheritance, method dispatching, class instantiation and so on to be modified during program execution, and 3- KRS [6] that has complete self-representation at run-time via meta-objects to affect the run-time execution. Instead, meta-objects in compile-time MOPs only exist during compilation and may be used to manipulate the compiling process. Two outstanding examples compiletime MOPs are Open C++[9] and OpenJava [10]. Though not as powerful as run-time MOPs, compile-time MOPs are simpler to implement and offer an advantage in reducing run-time overhead.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 describes the design and implementation of OpenC and Section 2 illustrates in detail how to use OpenC to develop a simple profiling library. Section 3 introduces the code coverage analysis tool which the author has implemented using OpenC. Future work and conclusions are given in last section.

It is often very expensive to make changes to legacy code on a large scale. There is a vast body of legacy C programs in use today and the procedural paradigm and lower-level programming constructs make C code even more difficult to maintain and evolve. In order to automate program translations for large-scale legacy C programs, we have implemented a meta-object protocol (called OpenC) for C that allows programmers to specify source- to-source program transformation libraries for applications written in C. The benefit to client programmers lies in that they can use the libraries to translate their application code in a transparent and repeated way by only adding simple annotations. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to bring the power of computational reflection to C with a MOP.

Even though the MOP mechanism depends on having an object-oriented meta-level language, the base-level language is not required to be object-oriented [13]. To implement OpenC, the base-level program is C program and the meta-level program is in C++, that is the language used in the underlying transformation engine ROSE[11].

The libraries developed with OpenC work at the metalevel providing the capability of structural reflection to inspect and modify internal static data structures. OpenC also supports partial behavioral reflection, which assists in intercepting function calls and variable accesses to add new behavior to base-level programs. Considering that the performance of systems (especially those that are computationally sensitive) should not be impaired by applying implementation of OpenC that offers control over compilation rather than over the run-time execution, in order to avoid run-time penalties.

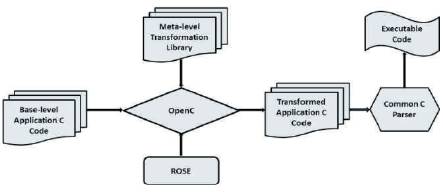

Figure 2 shows the high-level infrastructure where OpenC is used to fulfill source-to-source program translations. The base-level application is C source code and the metalevel library is developed with facilities provided by OpenC to perform transformations on the base-level code. OpenC takes the meta-level transformation library and base-level C code as input and generates the extended C code to address the concern expressed in the meta-program. The generated C code, which can be compiled by a traditional C compiler, is composed of both the original and newly translated C code that is placed in specific places in the program.

In this approach, the low-level support is from a program transformation engine called ROSE[11] that integrates EDG [12] as the frontend for C programs. ROSE is an open source compiler infrastructure that allows users to build source-to-source transformation tools that read and translate programs in large-scale systems [11]. It works by constructing an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) for the input source code and providing mechanisms to traverse and manipulate the AST. ROSE also supports regenerating source code from the AST[11]. ROSE is able to preserve all comments that appear in the source code, which are saved with the AST and can be obtained later by traversal. We have taken advantage of this to allow client users adding annotations to source code in the place of user comments. The annotation is used to specify a metaobject using keywords and special tokens, e.g., “//@OC::META_FUNCTION metaFunName.”

Figure 2. The infrastructure of using OpenC to perform program transformations

Similar to other MOPs, the top-level entities in the baselevel code, such as struct definitions, variables and functions, are represented by meta-objects in the metalevel program. For instance, a function meta-object contains sufficient information about the structure and behavior of the function and interfaces carefully designed to alter them. With OpenC, the source-tosource program transformations are performed in the following steps:

OpenC provides facilities to develop translation libraries that are able to transform C code in multiple scopes (e.g., manipulating a function, a struct, a file or even a whole project including multiple files). As an example, assume a user would like to create a new function A and call it from another function B. The translation scope can be the file (if function A and B are in the same file) or the whole project space (if A is generated in a different file than B).

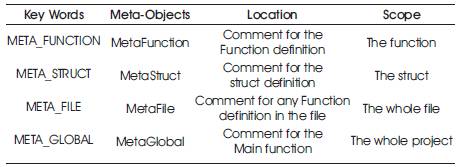

Four types of meta-objects, which are indicated in Table 1, are designed to support transformations of multiple scopes. They are types of MetaFunction, MetaStruct, MetaFile or MetaGlobal. The class from which the metaobject is instantiated is called the meta-class. The four meta-classes are all subclasses of the class named MetaObject. The member function OCExtendDefinition() declared in MetaObject should be overridden by all subclasses to perform callee-side adaptions for the definition of a function or a struct (e.g., adding a new variable in a struct, or inserting statements in a function). OpenC also supports caller-side translations by overriding the following member functions defined in MetaObject:

Usually different types of meta-objects can be used collaboratively in a transformation task. If multiple-level translations are involved, the sequence for applying these meta-objects has to be arranged carefully to avoid conflicts. Library developers are suggested to implement libraries following the principle of per forming transformations on small level first then a larger level; for example, translating an isolated function contained by a file before performing the filewide translations.

To allow client programmers to use libraries developed with OpenC by simply adding annotations to their base-level programs, OpenC provides a set of keywords to identify the annotations. Table 1 summarizes the features of these keywords, including the type of the meta-object corresponding to each keyword, the place in the application code where a keyword is added, and the translation scope. For instance, META_FUNCTION is a new keyword designed to designate a meta-function (i.e., the translation scope is function-wide), which is defined in the library code, to a function definition in the base code. In next section, we will illustrate how to use OpenC to implement a simple profiling library and then how to add an annotation to use the library.

Table 1. The Keywords Used As Annotation in Openc

In this section, the author outlines the implementation of the initial version of a profiling library that can be employed to show the distribution of execution time among all function calls in a system. The main purpose is to illustrate how OpenC can be used to implement a translation library and how the library can then be used to add the profiling capability to an existing C application in a transparent way. Profiling is known as a useful technique to help developers obtain an overview of system performance. Via a profiling tool, temporal characteristics of the run-time execution are collected to allow analysis so as to provide a general view on source locations where time is consumed.

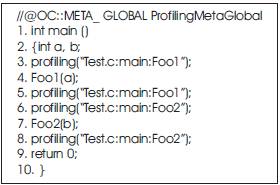

One general way to realize this is to build a library that calculates the running time by comparing the system time right before and after a function call. The library may provide an API, say profiling(char* pFunctionCall), which gets the identifier uniquely indicating a function call. The identifier includes the file name where the function call occurs, the caller’s function name and the callee’s function name. To use the profiling library to an application, the API is called before and after every function call in the source code as shown in Figure 3.

In this example with only two function calls (Foo1(a) and Foo2(b)) within the main function in the file Test.c, it may not seem a challenge to code manually for the purpose of implementing the profiling functionality. However, the situation becomes labor-intensive and error-prone when many more functions in different files are involved, which is always the case in larger applications.

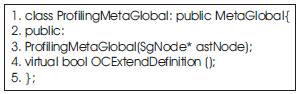

Using Open C, the process of invoking profiling around every function call in a large-scale system can be automated via code generation techniques. OpenC provides the ability to build the profiling library which automatically generates and integrates a new copy of the original application code and profiling code by manipulating the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) on a metalevel. To implement the profiling library affecting all functions in an application, the library programmers need to create a new meta-class inherited from class MetaGlobal, as shown in Figure 4. The subclasses of MetaGlobal are designed to perform translations for all the files in a system by merging individual ASTs for each file into a single big AST.

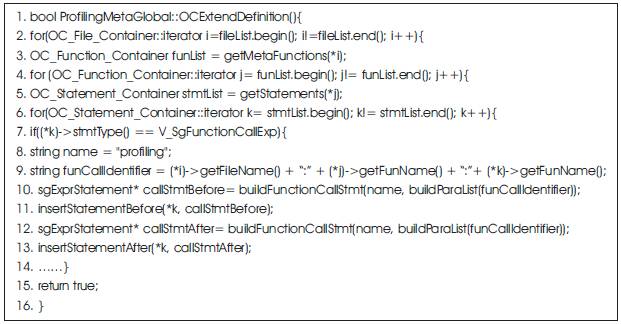

To build the profiling library, we override OCExtend Definition() to specify the translations. Figure 5 shows the code snippet implementing the overridden OCExtend Definition(). The file List in line 2 is a member variable defined in MetaGlobal as a container holding the handlers of all files in a project. The funList in line 3 contains all meta-functions representing all functions in a file. Line 2 and line 4 iterate through all functions in all files and line 6 loops through all statements in the target function to identify those function-call statements. Once a function-call statement is found, as show in line 10 and 12, two additional function-call statements are generated respectively by calling buildFunctionCallStmt(…) with the first parameter indicating the function name (profiling) and the second parameter as a parameter list. The only parameter is the identifier of the function call, composed of the file name (test.c), the caller’s function name (main) and the callee’s function name (Foo1 or Foo2), as denoted in line 9. Then the two function-call statements are inserted before and after the located function-call statement, as in line 11 and line 13. The resulting translations would be indicated as highlighted in line 3, 5, 6, 8 in Figure 3.

The design focus of OpenC is to automate program translations in a straightforward and transparent way, so that client programmers only need to add simple annotations to use the libraries. The details on how to perform the transformations are hidden from the client users. As denoted by the user comment in the first line in Figure 3, it is pretty convenient to use the profiling library by simply annotating the source code with a user comment starting with “@OC::.” In the annotation, the keyword META_GLOBAL is used to associate a meta-global object with the main function to perform project-wide translations. In this example, the meta-global object is instantiated from the meta-class ProfilingMetaGlobal, which can be replaced by any other meta-class as required to perform arbitrary transformations. Figure 4 shows the User-defined meta-class inherited from MetaGlobal.

Figure 3. The translated code with the profiling capability

Figure 4. User-defined meta-class inherited from MetaGlobal

The author has tried to use OpenC to develop libraries to solve real problems encountered in software maintenance, evolution and testing. In this section, the author briefly introduce a library of code coverage analysis implemented using OpenC.

Code coverage analysis is a means of determining the quantitative measure of the extent to which the source code of a program is covered by running a test suite. It is usually achieved by first instrumenting the source code or intermediate binaries with instructions that are used to navigate the generation of coverage data during program execution and then analyzing the collected coverage information to output a coverage report [15] .

There are a variety of coverage criteria used to measure coverage levels, among which the following ones are basic and commonly used:

Although path coverage is considered to be the most comprehensive, it is impractical to achieve due to the number of test cases growing exponentially to the number of branches [15]. All existing coverage tools for C programs support statement coverage, some supports analyze decision coverage, only a few are able to offer more than decision coverage analysis [15].

The library implemented with OpenC supports both statement coverage and branch coverage analysis by implementing two different types of meta-classes. Coverage analysis in different scope and granularity is also supported by creating meta-classes in different scopes, e.g., in a function, a file, or the whole project. Due to the easy-to-use characteristic of OpenC, client users can easily switch meta-objects to achieve the desired coverage information.

The coverage tool is highly configurable to perform code coverage analysis in different scenarios by utilizing different keywords. If a user would like to get the coverage report on a set of test cases for a single function, for example function Foo(), he or she only needs to add the annotation in the following comment, “//@OC::META_ FUNCTION CodeCoverage. ”If a coverage report on a test suite for all functions in a single file is needed, the user can add the following annotation in the comment attached to any function definition statement within the file “//@OC::META_FILE CodeCoverage.” Another scenario may involve multiple files or even the whole project. In this case, the annotation in a comment should be attached to the main() function definition as “//@OC::META_GLOBAL CodeCoverage.” Figure 5 shows an Implementing OCExtendDefinition() in meta-class ProfilingMetaGlobal.

The coverage report includes information about the frequency with which each part of the source code has been executed. It is presented in the form of an annotated version of the original source code. The information is very useful to determine hot spots, the code segments that have been visited frequently and cold spots that have not been executed at all. Besides, the report also contains the percentage representing the coverage level with a specific coverage metric, which provides a general view of how a set of test cases satisfy the coverage metric. A low percentage usually means that the test cases need to be improved in order to increase the possibility of detecting more bugs in the code.

Figure 5. Implementing OCExtendDefinition() in meta- class ProfilingMetaGlobal

The work described in this paper is focused on a brief summary of the OpenC framework that brings the power of computational reflection to C. With OpenC source-tosource program translation, libraries can be built and then applied in a transparent way. This can be especially suitable for developing libraries dealing with crosscutting issues like logging, profiling and check-pointing.

In traditional approaches, library users are usually forced to learn the specifications on how to use a library’s interfaces. However, to use libraries developed with OpenC, the only action required is to attach proper annotations to the source code and the underlying transformations are completely transparent to the users. It is also convenient to unplug the libraries by simply removing the annotation. The application code is kept intact because translations are performed on a generated copy of the original code.

Although it is more straightforward to use OpenC to implement libraries than directly using APIs of ROSE to manipulate an AST, there is a learning curve for library developers to get familiar with OpenC. We plan to create a domain specific language used on the top of OpenC (on a meta-meta-level) to make it even simpler to use.

The author’s experience shows that the MOP mechanism, as a way of program extension, can be used to deal with a widerange of problems by facilitating the implementation of source-to-source program translators.

There is a lack of infrastructure support for language extension in the way of building a meta-object protocol for an arbitrary language. Therefore we plan to build a generalized framework, named OpenFoo, suitable for extending an arbitrary programming language by creating a meta-object protocol for the language. And the design goal is to allow end-users to specify source-tosource program transformation of any kind via the MOP to existing programs written in the language.