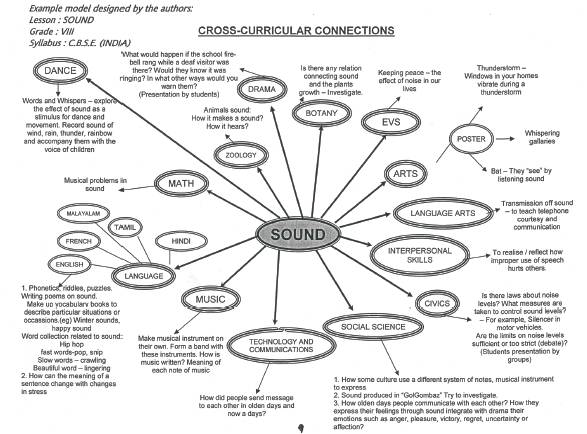

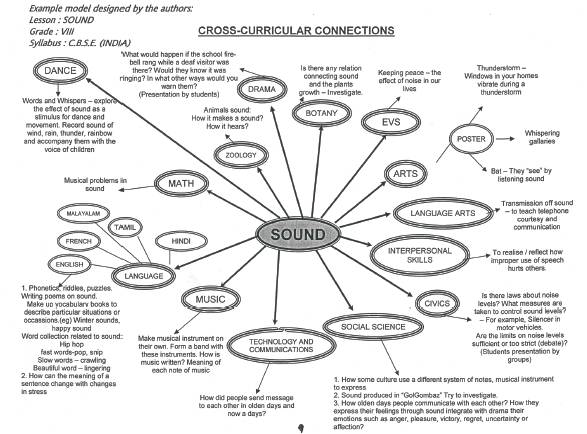

Figure 1. Cross Curricular links for the chapter SOUND

Students want to discuss each and everything related to the subject as well as the personal matters with their teacher. This shows that they trust their teachers so much than anyone else. So it is the duty of the teacher to teach the subject with more and more concrete examples and connections with the day to day life. They should connect the subject with all disciplines so that rather than opening the new memory location the information will store on the location which was already created on the brain. In the light of the above discussion researcher (authors) decided to carry out a research (article) on Cross Curricular Connections. Cross Curricular Connections to science instruction can result in rich and meaningful experience for students. The article that follows describes Cross-Curricular or interdisciplinary connections and their values to learners. Then, it lists specific considerations a Science teacher, or any other teacher, should consider before setting aside instructional time to make Cross Curricular Connections.

In traditional school programs, writing is taught only in English (language) classes, and teachers in other subjects depend on English department to teach the skills that students need to write in all other subjects. The educators all over the world understand the interactions of the various disciplines. Some teachers feel that they haven't enough time to discuss how their subject interacts with the other subjects. For example, in the subject Mathematics principles can be experienced in the other fields like Music, art, drama and sports. But unfortunately most of the maths teachers spend more on the Math skills rather than on the links to other areas.

Innovation in the field of education refers to technology based education such as e-learning, virtual class rooms, CAL etc.- Interdisciplinary / cross-curricular teaching involves a conscious effort to apply knowledge, principles,and / or values to more than one academic discipline simultaneously. The disciplines may be related through a central theme, issue, problem, process, topic, or experience (Jacobs, 1989). The organizational structure of interdisciplinary / cross-curricular teaching is called a theme, thematic unit, or unit, which is a framework with goals/outcomes that specify what students are expected to learn as a result of the experiences and lessons that are a part of the unit.

There seem to be two levels of integration that schools go through: The first is integration of the language arts (listening, speaking, reading, writing, thinking) (Fogarty, 1991; Pappas, Kiefer, & Levstik, 1990); the second involves a much broader kind of integration, one in which a theme be g i n s t o e n c o m p a s s al l c u r r i c u la r a r e a s. Interdisciplinary/cross-curricular teaching is often seen as a way to address some of the recurring problems in education, such as fragmentation and isolated skill instruction. It is seen as a way to support goals such as transfer of learning, teaching, students to think and reason,and providing a curriculum more relevant to students (Marzano, 1991; Perkins, 1991).

Apart from that the recent innovative way of learning a subject is using “CROSS CURRICULAR CONNECTION (Ccc). Cross curricular links are important for learning as learning depends on being able to make connections between prior knowledge and experiences and new information and experiences. When we give opportunity to the children to measure their progress towards their goals what they establish learning makes more meaningful. This will also motivate them and allow them to face new challenges with lot of confidence. Instead of using the prescribed text book we can use the Cross curricular activities where all subjects are linked also which involves music, drama, art, creative, writing, graphing etc.

There are various ways a science teacher might makeCross curricular connection. Certain skills from language, maths, art are naturally connected with science. Integration of variety of curriculum depends on the teacher. With careful planning, one can easily incorporate several different content areas in a lesson.

The cross-curricular approach, however, teaches a number of subjects using a theme or topic as a central core. For example, a topic on Sound may include some scientific investigations, various types of writing (English), mathematical surveys, collage (art), etc (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cross Curricular links for the chapter SOUND

The cross-curricular approach enables the teacher to provide a vehicle through which children can apply the skills and concepts gained from subject teaching. Furthermore, the children become aware of how to use, develop and extend the many skills they are gaining, theysee a purpose and value in having those skills, and the topic usually produces an end result whereas subject teaching tends to be on-going.

To reinforce the understanding that skills and knowledge gained through subject teaching are the “tools” people use to solve problems, make discoveries, communicate with others etc., the children will be made aware of which type of skills they are using when undertaking topic work, i.e., mathematical, scientific, etc. All topic works are carefully planned to ensure that they are complementary to the levels of subject teaching.

In its public draft of a framework for Science Education, the National Research Council's National Academy of Sciences (2010) has identified “Cross – cutting Elements” to describe two ways that Cross-Curricular contact may be integrated into science curriculum.

Science concepts connect across different science disciplines. Science make Social links to areas such as history, technology. The draft stated that the integration of Cross-Cutting elements could help students with an understanding of science that is “integrated, cumulative and usable.

Ccc help the students make sense of our world and develop the capacity to learn. The human brain increases capacity by making connections not merely by amassing information.

Ccc is more meaningful to students and helps them to understand the transferring knowledge. Our general objective is to improve learning and teaching. More specifically, we want to see the emergence of learners who can demonstrate a high level of basic competence, as well as deal with complexity and change. For this to happen, education needs to accommodate both the needs and design of the human brain. The overwhelming need of learners is for meaningfulness.

To accomplish that objective, we have to more clearly distinguish between the types of knowledge that students can acquire and how it can be applied to real life situations. The main distinction is between surface knowledge and meaningful knowledge. The former, involving memorization of facts and procedures is what education traditionally produces. Of course, some memorization is very important. The latter meaningful knowledge, however, is critical for success in the twenty-first century.

Surface knowledge is anything that a robot can “know.” It refers to programming and to the memorization of the mechanics of any subject. Meaningful knowledge, on the other hand, is anything that makes sense to the learner. A child who appreciates a plant as a miracle approaches the study of plants differently from a child who “engages in a task.”

Our function as educators is to provide students with the sort of experience that enable them to perceive “the patterns that connect (Bateson, 1980) (ie) Cross Curricular Connections.

An essential problem is that almost all our testing and evaluation is geared towards recognizing surface knowledge. We tend to disregard or misunderstand the indicators of meaning.

Present testing procedures tend not to accommodate both types of knowledge.

Even more tragic is the fact that, by teaching to the test, we actually deprive students of the opportunity for meaningful learning. Testing and performance objectives have their place. Generally, however, they fail to capitalize on the brain's capacity to make connections. By, intelligently using what we call active processing, we give students many more opportunities to show what they know without circumscribing what they are capable of learning. Testing and evaluation will have to accommodate creativity and open-endedness, as well as measure requisite and specifiable performance.

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, while students are learning the basic information in core are the advantages and disadvantages of theme in a classroom.

In these Subject areas, they are not learning to apply their knowledge effectively in thinking and reasoning (Applebee, Langer, Mullis, 1989)

Interdisciplinary/cross-curricular teaching provides ameaningful way in which student can use knowledge learned in one context as a knowledge base in other contexts in and out of school (Collins, brown newman,1989)

Many of the important concepts, strategies and skills taught in the language arts are “portable” (Perkins, 1986). They transfer readily to other areas. The concept of reading material in any content area. Cause and effect relationships exist in literature, science and social studies. Interdisciplinary/cross curricular teaching supports and promotes this transfer. Critical thinking can be applied inany discipline.

Interdisciplinary/cross curricular teaching provides the conditions under which effective learning occurs. Students learn more when they use the language arts skills to explore what they are learning, write about what they are learning , and interact with their classmates, teachers and members of the community (Thaiss, 1986).

This activity motivates the children and they get to make decisions about what they are learning. Students can increase their basic skills, positive attitudes, higher order thinking skills, team work, group learning, besides sensitive, leadership qualities etc.

Several researches have addressed the value of making Ccc using broad themes and ideas. Donovan and Branstord ( as cited in park Rogers of Abell 2007) explained that “instructional approaches that integrate curriculum have gained support from the field of cognitive science, where researchers suggest that learning big ideas and frame work is more powerful than learning individual or fragmented ideas.

Making connections merely for the sake of doing so is aimless. It needs purposeful and meaningful goals many opportunities exist for making connections to other science disciplines or non science disciplines. Before starting, however, teachers should examine the particular purpose for the connection, the ability to meet course-specific standards, the value to the other content. Considering these aspects can result in a rich and meaningful learning experience for students. Ccc lessons will encourage both the facilitator and students to worktogether.This integration will also help the students' problem solving skills and increase their creativity.

Teachers who use cross-curricular themes create active readers and writers by engaging students in authentic literacy tasks that emerge naturally from interesting and worthwhile topics and ideas. Authentic tasks are defined as “ones in which reading and writing serve a function for children…” and which “involve children in the immediate use of literacy for enjoyment and communication” (Hiebert, 1994, p.391). They focus on student choice and ownership; extend beyond the classroom walls; involve a variety of reading and writing opportunities; promote discussion and collaboration; and build upon students' interests, abilities, background, and language development (Hiebert, 1994; Paris et al.,1992). Crosscurricular themes integrate the language arts (reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing, and thinking) across a variety of content areas, such as science, social studies, art, and so forth.

Research findings indicate that good readers connect and utilize ideas and information from a variety of previous life and literacy experiences (Anderson et al, 1985). Sustained reading of interesting texts improves reading comprehension and enhances enjoyment (Fielding & Pearson, 1994; Reutzel & Cooter, 1991). Over time, the effect is that comprehension improves as students read more (Hertman & Hartman, 1993). Therefore, to increase understanding, students should have experience reading a variety of texts, including narrative and expository literature, as well as “real world” materials such as brochures, magazine articles, maps, and informational signs. These varied experiences enable young readers to build a foundation that will prepare them for future “real life” reading and writing tasks. Because our lives require us to integrate what we have learned in an interdisciplinary manner, teaching children through merged disciplines better prepares them for applying new knowledge and understandings. Additionally, when students view their learning as having personal relevance, they put more effort into their schoolwork and achievement. (Willis, 1995).

Students and teachers alike enjoy reading and learning about topics and ideas that are interesting and challenging. Along with enjoyment, cross-curricular thematic instruction offers a number of other advantages (Cooper, 1993; Fredericks, Willis, 1995). Thematic teaching enables students to:

Cross Curricular Connections is staffed with educators experienced in all disciplines and grade levels. Ranging from elementary literacy development to science and health to advanced level humanities expertise, team of educationalist has not only an understanding of classroom practices, but also a keen awareness of and focus on current trends in education, including an emphasis on teaching and learning standards.

Most organizations have a vested interest in promoting educational programs in the United States, and can help to create curricular resources with sound educational content that use age – appropriate pedagogical techniques and are sensitive to today's diverse learners.

As technology and the continuing communication resolution make our world ever smaller and more complex, individuals will increasingly need to synthesize multiple strands of information to make informed decisions about their lives and their communities. Because these strands of information will not come equipped with tidy labels of Chemistry, Art, or History, people will need to connect what they know to new information to construct new knowledge and craft better solutions. Individuals who succeed in making those connections and in understanding some of the ways in which mathematics, technology, and the sciences depend on each other will have achieved one facet of what Science for All Americans defines as science literacy.

Fortunately for science education reformers, curriculum connections is an idea whose time has come. Available literature on the subject grows daily, and conferences publicizing interdisciplinar y curricular models attract\significant numbers of participants. Nonetheless, even in schools that appear to be at the forefront of establishing interdisciplinary connections, the gulf between the humanities and the sciences often seems impassable. For example, the humanities and sciences are still taught in separate blocks in many schools that belong to the Coalition of Essential Schools, a nationwide reform movement that stresses curriculum connections (Sizes, 1989).

Educators should work to bridge this chasm for two main reasons. First, to be science literate, citizens must be able to draw on knowledge inside and outside the fields of science and mathematics. Second, and on a far more pragmatic level, as American students are called on to master an ever expanding body of knowledge, using junctures across the curriculum will 1. Eliminate needless redundancies and use time more efficiently

Saskatchewan curricula are designed to develop four interrelated Cross-Curricular Competencies that synthesize and build upon the six Common Essential Learning's. The following competencies that synthesize and build upon the six Common Essential Learning's. He following competencies contain understandings, values, skills, and processes considered important for learning in all areas of study.

An effective learning program is purposefully planned to connect the parts to the whole. The Board Areas of Learning, Cross-Curricular Competencies, area of study K- 12 aims and goals, and grade – level outcomes are interconnected. It is important that teachers keep this interconnectedness in mind when planning.

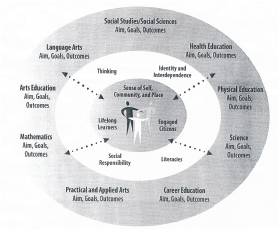

Interdisciplinary links are the most obvious way to approach curriculum connections. Whether through examining the mathematical structures of music or studying the principles of carbon dating while learning about Mayan culture, interdisciplinary connections make scientific principles tangible to a wide variety of individuals and provide an efficient method for designing lessons and strengthening the content learned in several subjects at once (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conceptual Foundations for Saskatchewan Curriculum

Learning in multiple and meaningful contests enhances student' abilities to build knowledge and understanding of science and its relationship to other disciplines.

Doing science every day is one way of learning science, and young people should be encouraged to discover science in their homes, their backyards, and their communities.

One of the greatest challenges to the teacher contemplating using Cross Curricular Connections as an approach is the relinquishing of power within the classroom. Gone is the age-old view that children are vessels to be filled with knowledge or as Paulo Friere calls it 'Banking education'. Rather, in agreement with Piaget's view, pupils are co-constructing Knowledge as a community with the teacher. Freire sees the community as a chance for all involved to be both teacher and learner at the same time and the purpose of learning as becoming a critical thinker, which involves asking difficult questions.

We live in a constantly changing, complex and socially challenging world where you can no longer expect to have one job for life. The most valuable skill our children can learn, to help them function as critical and creative citizens of society, is the ability to both think critically and apply their skills to new situations. The National Curriculum identifies key and thinking skills as the cross-curricular focus for all learning, some of which include learning how to learn, problem solving, social skills, communication, use if ICT, information processing, enquiry, reasoning, creative thinking and evaluation. The author believe that Cross Curricular Connections provides a safe social environment in which to acquire and apply these skills, some of which are utilized within the imaginary world of drama conventions, where pupils have access to experiences and situations normally unavailable within the confines of the average classroom and standard curriculum.

It is just three of these skills the author want to look at more closely within the confines of this literature review, creativitymeta- cognition and critical thinking. Rogers advocated this concept when talking about personalized learning, where he suggested the teacher act as facilitator. Rogersbelieved that there are four clear threats to the development of a pupil centered approach such as Cross Curricular Connections, which include: teacher fear of power sharing, the risk of trusting teacher/pupils, student reliance on direction and finally, the perceived threat to school organization and management systems. Finally, the cross-curricular connections tables provide suggestions of skills or content from other subject areas that align with the content or skills of the current chapter or section. The crosscurricular skills or content may be taught or reviewed in conjunction with the skills or content from the current subject area chapter. Children learn through a process of building schemes and connections based upon prior knowledge. Children can only build these schemes through connecting their current experiences with previous ones. In other words, prior knowledge is the base or foundation on which new knowledge is constructed. Effective teachers recognize, when, connections to prior knowledge can be made. These teachers use crosscurricular connections to present related information in a variety of situations and contexts.

Cross Curricular Connection is thus a specific teaching methodology which helps the students to understand the various disciplines connected in one particular form. Teachers should use this as their main teaching tool in their class room. This approach was expected to increase the student achievement and improve facilitation and students attitudes about teaching and learning. Cross Curricular Connections in lessons will encourage both the facilitators and Students to work together. This integration will also help the student's problem solving skills and increase their creativity.

Science teachers can enhance and deepen the learning when making cross-curricular connections to their own curriculum. Many avenues exist for making connections to other science disciplines or non-science disciplines. Before proceeding, however, teachers should examine the particular purpose for the connection, the ability to meet course-specific standards, the value to the other content, the potential harm to the base-content, and his or her competency in the other content. Considering thesefactors can result in a rich and meaningful learning experience for students.

Each and every one in this century needs to be creative and lifelong learners and this Cross Curricular learning will develop these skills to the learners.