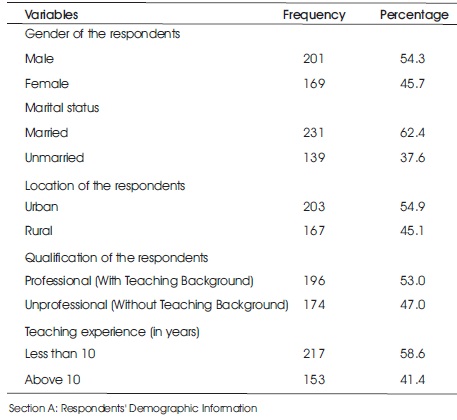

Table 1. Demographic Information of the Participants (N = 370)

The sample population for this study comprised 370 Junior Secondary School teachers in Kwara State. Simple random sampling technique was used to select both the respondents and schools used for the study. The quantitative data were collected through a 6-point Likert scale questionnaire. The data were analyzed using simple percentages and t-test analysis. The results show that there is no significant difference between the attitude of female and male teachers towards the inclusive classroom. The result shows that there is a significant difference between the attitude of teachers from urban areas and those from rural areas towards the inclusive classroom.

Worldwide, there has been an emphasis on the need to extend access to education for all. This has been verified through many international conventions such as; the UN Convention on the Right of the Child, 1989, the Salamanca statement on special needs education, UNESCO, 1994, and the UN international convention on the Right of the Persons with Disabilities, 2000. Nigeria has, however, signed and ratified the UN Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 24 states that all schools must be inclusive of, and accessible to all children including those with disabilities. Besides, Nigeria is a signatory to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of which Goal number 4 is targeted that by the year 2030 all school-age children, including those with disabilities, must have access to qualitative, functional and effective basic education.

Moreover, the Nigeria National Policy on Education has specifically made it that education must be inclusive at all level. The implication of this is that all children, including those with disabilities, must have the right to qualitative, functional and effective basic education. The Nigeria Universal Basic Education Act of 2004 also provides that there should be free and compulsory basic education for all school-age children. However, the implementation of inclusive education in Nigeria has largely been achieved on paper rather than in practice (Ajuwon, 2008; Iwuamadi & Mang, 2016). This is to say that some of the energy dissipated on inclusive education by Nigerian education scholars and policymakers is only on paper. Little or no efforts have been made to make inclusive education work in all our schools up till now. Not surprising that Nigeria still holds the highest record for Out of School Children. The population of Out-of-School children in Nigeria is at 10.5 million out of the 57 million in the world (Adebisi et al., 2014).

It seems governments at all levels in Nigeria have not acquainted themselves enough with the global urgency and exigency of the need to meet all-important Goal 4 of SDG. There does not appear to be any concerted efforts on the part of governments to take the SDGs seriously. Every bit of Nigeria's education policy breaches the spirit and aims of the SDG goal number 4. Since 1960, the country education system has always been tailored to promote exclusion rather than inclusion. The economic system of Nigeria remains capitalism, hence, social services, including education, are seen as non government responsibility, education is seen as business and students are seen as customers (Adetoun et al., 2016). The problems are not limited to Nigeria alone, most of the African countries see education as 'White Elephant' project. This has posed great concerns to policy makers and educational administrators. Thus, in the past three decades, there has been a series of an international debate on inclusive education.

In Nigeria, for instance, the awareness about inclusive education is still at the infancy stage. Hence, the success of the education of students with special educational needs has been a big challenge to Nigerian educational administrators and policymakers who are sceptical about bringing both the normal and disabled children into the same classroom for teaching and learning purpose. Students with special educational needs are facing different challenges ranging from and inadequate training for teachers to handle a student with a disability successfully, inflexibility in the course curriculum, classroom size problems, bullying of children with disability, not given children with disability the kind of attention they deserved and social discrimination among peers. More importantly, the unpreparedness and negative attitude of teachers toward inclusive education have posed a great challenge. Many researchers have investigated teachers attitude towards inclusive education and most of them have come up with a result that shows different teacher's attitude, either negative or positive. For instance, researchers such as Alharthi and Evans (2017); Omede and Momoh (2016); Timothy et al. (2014); Buford and Casey (2012); Machi (2007); have found unfavourable attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education. Omede and Momoh (2016) and Buford and Casey (2012) attributed the negative attitude of teachers toward inclusive education because of the teacher's lack of skill, and fear of handling such students. However, there are many studies such as Oluremi (2015); Walker (2012); Fakolade et al. (2017); and Khan (2011) that have found favorable attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education. Oluremi (2015) and Walker (2012) give a reason for the teacher's positive attitude towards inclusive education which they said it depends upon teacher's efficacy, experience, training, adequate flexibility in course curriculum and type of disability, and size of the class among others.

Though the journey towards inclusive education in Nigeria has begun, yet its speed is too slow to be implemented in every corner of the country (Ajuwon, 2008). For its successful implementation, there is an utmost need to explore more on teacher's attitudes toward inclusive education because they are key service providers in handling such students (Rakum, 2017; Sambo &Bwoi, 2015). Hence, the present researcher has attempted to establish the nature of attitudes of junior secondary school teachers towards inclusive education in the hope that the results may be useful in the implementation of inclusive education as it was reflected in the United Nations global strategy of Education for All, as well as the Nigerian National Policy on Education.

Kwara State Government has commenced a policy on inclusive education. This policy, however, has remained largely unimplemented as nearly all the public primary and secondary schools in the state are not inclusive. Some of the schools were never accessible to the children with disabilities, despite that the populations of these children who are out of school in the state have reached an alarming level. According to Nigeria's current population statistics, Kwara State is projected to have an average population of about 270,000 children with different disabilities. Out of this population, only an average of 10,000 is currently receiving some form of basic education through the few special needs schools and inclusive units in both public and private primary and secondary schools and learning centres (Ademefun, n.d).

Kwara State currently has a total of seven registered Special schools and learning centres (both Public and Private) for children with disabilities with the combined enrollment capacity of about 2000 pupils (Ademefun, n.d). In addition to inadequate human, material and financial resources most of the special schools lack modern basic educational infrastructure. Besides, only a few are sited in an urban area where social amenities are available. Some of these schools/centres are located in distant (often hardto- reach) areas that lack basic infrastructures such as electric power supply, good roads, health facilities, and portable water. The obvious cause will be very exclusive and inaccessible regular primary and secondary schools. This makes it impossible for children with disabilities to attend schools within their locality closest to their residence as other normal children. This has imposed the avoidable hardship on most of these children as they have to travel long distances to their school.

Further compacting this problem is the inadequacy and non-implementation of an appropriate legal and policy framework on inclusive education for children with disabilities in the state. While Kwara state has developed a good policy framework in this direction, there is little or no effort at the implementation of inclusive basic education in the state. However, good policy and legal frameworks are necessary to serve as implementation guide especially concerning statutory planning and budgeting, as well as standard regulation especially concerning enforcement of compliance, monitoring, and evaluation (Adebisi et. al., 2014).

Another key causal factor is the low public awareness in the state on issues of inclusive education especially among public officials and policymakers, professionals, parents, and other stakeholders which have made it difficult to increase their interest and commitment to inclusive and accessible basic education for children with disabilities. This is also responsible for the inability of stakeholders to collaborate effectively on how to make all public and private primary and secondary schools inclusive and accessible for children with disabilities (Ajuwon, 2008).

The unconcerned attitude of educational professionals such as teachers, caregivers, social workers, and medical practitioners among others has also made it difficult to effectively implement inclusive basic education for children with disabilities in the state (Fakolade et al., 2017). This attitude might be as a result of their low capacity building opportunities through relevant academic and professional training programs administered by tertiary institutions (Iwuamadi & Mang, 2016). For instance, the training of pre-service teachers is still not all-encompassing, the training tends to focus on separate service delivery for learners with special educational needs. The pre-service training process does not view training in special needs as an integral and important part of the general teacher education curriculum. A situation that made most of the teachers lack in empathy and insight into the phenomenological world of the learner with unique special educational needs.

Hence, it results in teachers' nihilism attitude towards students with disabilities as well as their acceptance in mainstream schooling Thus, learners find themselves physically present in the mainstream schools but their special educational needs are not catered for. This has resulted in the frustration of these learners due to their inability to cope with academic work provided within the framework of mainstream education. Consequently, they would drop out of the school system and inclusive education would be defeated.

To determine the attitude of teachers towards inclusive classrooms in Kwara State

H01: There is no significant difference between the attitude of female and male teachers towards inclusive classrooms.

H02: There is no significant difference between the attitude of urban and rural teachers towards inclusive classrooms.

H03: There is no significant difference between the attitude of married and unmarried teachers towards inclusive classrooms.

H04: There is no significant difference between the attitude of professional and unprofessional teachers towards inclusive classrooms.

H05: There is no significant difference between the attitude of less and above 10 years of teaching experience teachers towards inclusive classrooms.

This study was carried out during the 2017/18 academic session. The population for this study was comprised of all junior secondary school teachers in Kwara state. Available statistics show that there are 7903 teachers in a junior secondary school in Kwara state (Kwara State Ministry of Education and Human Capital Development, 2016). Using the research advisor (2006) at a 95% margin of error and 5.0% confidence level, 370 was the suggested required sample size for this population. Random sampling technique was used to select the sample. The sample consists of both male and female teachers. For this study, a questionnaire was personally designed by the researcher after a careful review of the related literature and it is titled: "Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusive Classroom Questionnaire (TATICQ)". The instrument comprises of two sections A and B. Section A focus on demographic data of the respondents which include information on gender, location, marital status, educational qualifications, and years of teaching experience while section B consists of 15 items on teacher's general attitude towards the inclusive classroom.

Section B of the instrument has questions that require the participants to indicate their level of disagreement or agreement with the items on 6-point Likert-type scale format of Strongly Disagree-1, Disagree-2, Not Sure but tend to Disagree-3, Not Sure but tend to Agree-4, Agree-5, and Strongly Agree-6. To determine the reliability of the instrument, a test-retest approach was used. The instrument was administered to forty (40) respondents and after three weeks interval, the instrument was re-administered to the same forty (40) respondents. The two sets of scores were correlated using Pearson's Product Moment Correlation formula which revealed a coefficient of 0.76 and was adjudged good enough to carry out the study. The average point is 1+2+3+4+5+6=21/6=3.5. Hence, the mean for decision making will be 3.5. Scores from 3.5 and above will be considered positive while scores below 3.5 will be considered negative. The analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data was done in line with the research questions. Percentages were used to analyse the demographic data of the respondent while Means, Standard deviation, rank order for the descriptive data. While t-test was used to analyses the hypotheses formulated for this work. All these statistical methods were carried out through the use of Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) version 20.

From Table 1 it was shown that an overwhelming majority (54.3%) of respondents were female teachers while (45.7%) were male teachers. Also, 62.4% of the respondents were married while the remaining 37.6% were not married at the time of this research. The data in Table 1 also revealed that (54.9%) of respondents were living in the urban area and 45.1% of the respondents were living in the rural area. Furthermore, the data in the above Table 1 indicated that (53%) had their certificate in education making them professionally trained teachers. However, the same table shows that majority (58.6%) of the teachers has worked for less than 10 years while the remaining 41.4% have worked for over 10 years.

Table 1. Demographic Information of the Participants (N = 370)

Table 2 shows that the respondents gave a positive response to items 2, 3, 4, and 5. The respondents also gave a positive response to item 13, 14 and 15. The grand mean of all respondents on all the statements of the TATICQ were 3.54. This mean indicates an attitude that falls between response numbers 3 and 4, that was between "not sure but tend to disagree" or "not sure but tend to agree", but leans heavily towards 4, which pertains to the response "not sure but tend to agree" on the questionnaire scale. A response means which lent towards 3 would be closer to "not sure but tend to disagree". Higher scores indicate more favorable views towards the inclusive classroom.

Table 2. Mean Score Showing the Response of Teachers on Their Attitude Towards Inclusive Classroom (N = 370)

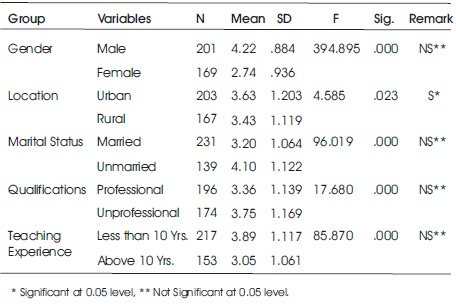

From Table 3, it can be observed that, although male teachers recorded a higher mean score of 4.22 than the mean score of 2.74 for female teachers. And since the mean score of male teachers was higher than that of their female counterparts, it follows that male teachers have a more positive attitude towards the inclusive classroom than their female counterparts. However, the difference in these mean scores was not statistically significant at P>0.05. This was because when considered the calculated f-value of 394.8 with its significant value of .000 which was less than alpha value 0.05 (p < 0.05). Hence, the H01 was accepted and the researcher's H01 is retained; that is to say that, there is no significant difference between the attitude of male and female teachers towards the inclusive classroom.

Table 3. Showing Significant Differences Between Variables

From Table 3, it can be observed that, although teachers from urban areas recorded higher mean score of 3.63 than the mean score of 3.43 for teachers from rural areas. This shows that teachers from urban areas have a higher positive attitude towards inclusive classroom than teachers from rural areas. However, the difference in these mean scores was statistically significant at P>0.05. This is because when considered the calculated f-value of 4.585 with its significant value of .023 which is greater than alpha value 0.05 (p > 0.05). Hence, we cannot accept the H02; that is to say that, there is a significant difference between the attitude of teachers from urban areas and those from rural areas towards the inclusive classroom.

From Table 3, it can be observed that the mean score of the married (4.10) is higher than that of teachers that are unmarried (3.10) suggesting that teachers who are married have a significantly more favorable attitude towards inclusive classroom when compared to the single participants. However, the difference in these mean scores was not statistically significant at P>0.05. This is because when considered the calculated f-value of 96.02 with its significant value of .000 which is less than alpha value 0.05 (p < 0.05). Hence, the H03 was accepted and the researcher's H03 is retained; that is to say that, there is no significant difference between the attitude of married teachers and those that are not married towards the inclusive classroom.

From Table 3, it can be observed that, although teachers who were not professionally recorded higher mean score of 3.75 than the mean score of 3.36 for teachers that were professional with an education background. This means that the non-professional qualified teachers tend to have a higher favorable attitude towards inclusive classroom than professionally qualified teachers. However, the difference in these mean scores was not statistically significant at P>0.05. This is because when considered the calculated f- value of 17.68 with its significant value of .000 which is less than alpha value 0.05 (p < 0.05). Hence, the H04 is accepted and the researcher's H04 is retained; that is to say that, there is no significant difference between the attitude of professional teachers and those that are not trained teacher towards the inclusive classroom.

From Table 3, it can be observed that, although teachers who are having work experience less than 10 years recorded higher mean score of 3.89 than the mean score 3.05 for teachers with above 10 years working experience. This shows that teachers who are having work experience less than 10 years tend to have a higher favorable attitude towards the inclusive classroom than teachers with above 10 years of working experience. However, the difference in these mean scores were not statistically significant at P>0.05. This is because when considered the calculated fvalue of 85.87 with its significant value of .000 which is less than alpha value 0.05 (p < 0.05). Hence, the H05 was accepted and the researcher's H05 is retained; that is to say that, there is no significant difference between the attitudes of teachers having less than 10 years and those above 10 years teaching experience towards inclusive classroom.

The major findings of this study revealed that the teachers' attitude towards inclusive classroom in Kwara State is neither satisfactory or average. It was found that there is no significant difference between the attitude of female and male teachers towards the inclusive classroom. It is also found that the attitude of male teachers has a positive attitude towards inclusive classroom more than their female counterpart. This is in contrary to Fakolade, et al. (2017) submission that female teachers have higher positive attitude towards inclusive classroom more than their male counterparts. This contradiction may be due to the timing interval of the study.

The present study indicates that there is a significant difference between the attitude of urban and rural teachers towards the inclusive classroom. It is also found that the attitude of teachers from urban areas recorded higher positive attitude towards inclusive classroom more than teachers from rural areas. The present study indicates that there is no significant difference between the attitude of married and unmarried teachers towards the inclusive classroom. It was also found that the Unmarried teachers have a positive attitude towards inclusive classroom more than that are married teachers .

However, it is found that there is no significant difference between the attitude of professionally trained teachers trained and those who are not towards the inclusive classroom. It is also found that teachers who are not professional recorded higher positive attitude towards inclusive classroom than teachers that are professional with an education background. This finding, once again, is in contrary to that of Fakolade et al. (2017) finding that a professionally qualified teacher tends to have a more favorable attitude towards the inclusion of special need students than the non-professional qualified teachers.

The last findings of this study revealed that there is no significant difference between the attitudes of teachers having less than 10 years and those having above 10 years of teaching experience towards inclusive classroom. It is also found that teachers who are having work experience less than 10 years recorded higher positive attitude towards inclusive classroom more than teachers with above 10 years of working experience. Tl need students more than teachers that are married.

This study suggests that the attitude of teachers towards inclusive classroom must be tested on some other variables such as pay structure, family background, class size, and subject the teacher teaches, among others. Also, similar studies can be conducted by taking a large sample of teachers from other parts of the country. Finally, further studies should be done at various levels of education in Nigeria; this will assist in achieving education 2030 agenda.