Figure 1. Characteristics of Healthy Perfectionist

Naturally humans strive to do their work. But when it exceeds a limit, it becomes neurotic and also not healthy perfectionism. Perfectionism is always not pleasurable, and people typically confuse their talents and capabilities with their perfectionism. In fact, perfectionism interferes with a person's ability to do well (Hummel, 2000). This paper reveals about the risk of self harm due to perfectionist's thinking.

Cognitive psychology tends to study the individual and mental systems within the individual brains. Every human being has the patterns of thinking, and this may impact on our emotional state and behaviour. Exaggeration of any irrational thoughts of human beings lead to cognitive distortion. Common cognitive distortions that affect our personality, work, and relationship, are catastrophizing, personalization, filtering, polarized thinking , overgeneralization, mind reading, control fallacies, emotional reasoning, perfectionism and blaming. Of these, Perfectionism often renders dissatisfaction with the current capabilities of an individual, thereby instigating endless search for the meaningful accomplishments by setting their species apart from all others. Webster defines perfectionism as “a disposition to regard anything short of perfection as unacceptable”. The degree of perfection vary from person to person, but all perfectionists set lofty and often unattainable goals. Perfectionism exacts a great toll on individuals who think that only through perfection will they be able to gain fulfilment, success, love, and acceptance of others. The pressures and burdens of perfectionism are based on anxieties about being less than perfect and about being less acceptable (Greenspon, 2012).

The inspiration for this article is that, many individuals have come across the experience of stress to expose their perfection in most of the areas in their life. According to Aaron Beck, perfectionism is a type of cognitive distortion. But many of us are not yet aware of the cognitive distortions, which generate positive and negative influences in one's life. The important goal of this current paper is to reveal that there is a chance of getting self harmed due to perfectionism in a distorted thinker. By knowing the facets of perfectionism and their dimensions, one can be aware of various forms of self harm.

Perfectionism may be regarded to have both a positive and negative influence in one's life. Hamachek (1978) viewed perfectionism as a manner of thinking about behaviour and describes two different types of perfectionism, normal and neurotic, that form a continuum of perfectionist behaviours (Kendrick & Johnsen, 2005). Normal perfectionists are unable to feel free and to be less precise as the situation permits. Neurotic perfectionists are unable to feel satisfied, because they never seem to do things well enough (Cranab & Raja, 2014).

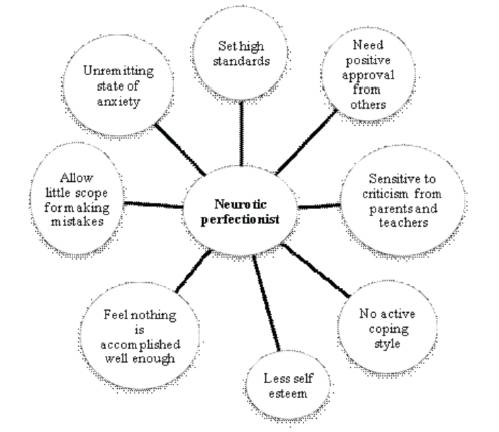

The characteristics of healthy and neurotic perfectionists (Schuler, 1999; Roberts & Treasure, 2001; Evans, 2013) are represented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Characteristics of Healthy Perfectionist

Figure 2. Characteristics of Neurotic Perfectionist

The six dimensions of perfectionism (Frost 1990, Brustein. 2013) are: Excessive concern over mistakes, Excessive high personal standards, High parental expectations, Parental criticism, Exaggerated emphasis on precision, Order and organization and Doubts about actions. They are summarized briefly in the following sections.

Perfectionists have excessive concerns over mistakes. They have the tendency to react negatively to mistakes, to interpret mistakes as equivalent to failure, and to believe that one will lose the respect of others following the failure. Equating of making mistakes with failure can make others to evaluate the individual in a similar fashion. Perfectionists concern over mistakes with a high frequency of mistakes and with a low frequency of mistakes were examined (Patterson, 2008). People with high perfectionism have concern over mistakes and react with more negative mood, lower confidence, and a greater sense that they have to improve better compared to low perfectionists’ concern over mistakes. Furthermore, high perfectionists have concern over mistake to see their performance as less intelligent, compared to others and were also less willing to share their performance results (Brustein, 2013). The subjects who were high in perfection have concern more over mistakes and they lead to be almost exclusive to the high-mistake-frequency condition.

Setting high standards of performance for self and/or others rather than having standards imposed; ensuring interactions and transactions are ethical and conveying integrity to personal work standards (Gould, 2012). Regarding the self oriented perfectionist, they set high standards for themselves and stress the importance of meeting those standards. Other oriented perfectionism involves the tendency to set excessively high standards for others. Socially prescribed perfectionism involves the tendency to believe that other people set excessively high standards and are overly critical when these standards are not met (Frost, Glossner, & Maxner, 2010). Hence the high standards of performance accompany the critical self-evaluations and when they exceed a limit, they lead to neurotic perfectionism.

The fusion of perfectionism and parenting emerges out in three ways such as,

(i) Parents are perfect in their own lives,

(ii) Parents wish for perfection in their own children and

(iii) Children strive for perfection for their own reasons (Szymanski, 2011).

Parents who demand perfection from themselves are almost certain to pass on those demands to the people around them, especially to their children. If the parents reward the children vigorously for high performance, the pattern of perfectionism is ever-present and reinforced. The children may become perfectionists for survival, but for no other reason.

Some parents try to be more perfect in their own lives. When children see their parents imposing perfectionistic standards on themselves, the children may learn a perfectionistic style by modeling their parents' behavior, even if the parents don't require it. If perfectionistic parents don't praise their children, the children probably will assume that they need to be perfect, just as the parents are trying to be perfect. Their children also fall in line with the same mode and become perfectionists just to gain approval (LeBlanc, D, 2006).

Parents who want their children to be perfect often withhold approval. Children may respond to this environment by trying all other means to perform well, just to receive affirmation. Sometimes parents praise children only for a certain level of performance. In rewarding only perfect performance, parents almost force children to become perfectionists. The more the perfect behavior is reinforced, the more the perfectionism becomes part of some children's personality style. In either of these situations, the children will pay the price for perfectionistic living. They may become aware that the costs outweigh the benefits, and when they realize that the burden began with parental expectations, they may rebel (Szymanski, 2011).

In some cases, the child strives to fulfil his/her parental expectations, even though the child derives no pleasure in doing so. At the same time, they do not feel free to act in their own way which will separate them from their parents (Stivers, 1991). Such early adolescents may make few emotional demands, withdraw their duties, become depressed, and get quietly pre-occupied with in themselves.

The harmful effects of parental criticism on children's emotions, academic achievement, peer relations, and physiology, including increased production of stress-related harmones are potentially damaging to brain development (Barish, 2009).

Much of parental criticism is well-intentioned, motivated by a desire for their children to improve, and eventually succeed, in a competitive world. In these instances, parents criticize their children because they are anxious about their children's future. They regard their criticism as constructive, or not as criticism at all, but rather as instruction or advice. Many parents feel justified in their criticism when they make an effort to balance criticism with praise. Even the parents are willing to offer praise for their child's good behavior and they do not regard themselves as critical. Same parents are aware of its seriousness. They believe that, it is their 'right and responsibility' to be critical to their children, in order to prepare them for the demands and responsibilities they will face as adults. In giving their criticism, these parents believe that, they are doing the right thing. They, therefore, continue to criticize, despite its bad effects (Barish, 2013).

Perfectionists are precise thinkers and employ plans and procedures for both their personal and professional lives, by avoiding the unexpected things (Perfectionist pattern (15 to 16), 2012). Perfectionism denotes an organized and orderly approach to life and the tendency to pursue tasks and goals in a conscientious manner. These qualities are based on self-disciplne, self-restraint, and control of impulses (Cattell & Schuerger, 2003). The healthy perfectionist pursues goals in an orderly and persevering fashion, and achieve goals in a timely manner. And also they are regarded as hardworking, responsible, and reliable. Once obstacles arise, to reach their goal even though when they are in order and organized, a healthy perfectionist can take steps to overcome that. But in the case of neurotic perfectionist, when there is some hurdle to finish their task in an ordered manner, they feel drained, anxious and depressed.

It reflects the level of confidence that people have about their ability to complete tasks (Frost & Steketee, 2002).

Compared to non-perfectionists, perfectionists assign greater importance to the task at the outset, report higher levels of negative affect when the evaluative component of the task are emphasized, and follow the task. They were more likely to report that they should have done better. Even though the perfectionist completed their task they always have a doubt about their task (Walters, 2004) .

Perfectionism and self-criticism are associated with self harm in clinical and community populations. A perfectionist individual believes that others hold unrealistic expectations of them, needs particular attention because, it can decrease the threshold above which negative life events lead to distress (Hawton et al., n.d.)

Self-harm or self-injury is a deliberate attempt to cause injury to one's body without the conscious intent to die (Reeves, 2013). Such behaviour includes, self- cutting, burning, biting, chemical abrasion, head banging, and embedding objects under the skin. Often the behavior is kept hidden and may become chronic.

Perceptions of greater parental rejection were associated with higher levels of both intra and interpersonal maladaptive schemes which, in turn, influenced corresponding intra and interpersonal motivations for self injury (Quirk et al., 2014). The socially prescribed perfectionism (i.e., the perception that others require perfection of oneself) predicted concurrent levels of suicide potential (Hewitt, Caelian, Chen & Flett, 2014). The six dimensions of perfectionism presented previously are differentially associated with psychological distress. The self-harming people, those who self-poisoning or self-injuring themselves due to some psychological distress, display higher levels of perfectionism (Davies & Phillips, n.d.). The average European rate of self-harm and attempted suicide for persons over 15 years is 0.14% for males and 0.193% for females.( http://www.anxietyzone.com/conditions/ self_harm.html). Perfectionistic Self Presentation (PSP) facets are associated with suicidal behaviour in adolescents (Roxborough, et al.,2012).

Perfectionism is a sad treadmill which can only lead to intense anxiety, fear, self harm, catastrophizing, and predictably unpleasant experiences. Having a sense of healthy perfectionism requires balance. It means that although anyone wants to excel and be ambitious, they must know at the same time how to match their intention with a strategy that works and produce the result they want. People who pressurize themselves or get pressured by outside sources to be perfect give themselves a hard time when reasonable or unreasonable goals are not achieved and mistakes are made. Failure to view learning and the human experience as ongoing processes creates dangerous distortions. It is the role of parents and teachers to show the reality of life in a positive way.