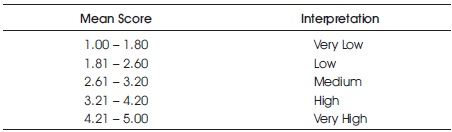

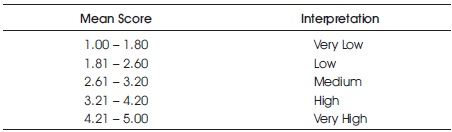

Table 1. The Mean Ranges and their Interpretations

In Vietnam, middle or high-ranking leaders and managers are required to have knowledge of politics. Those who hold leadership roles in both the private and public sectors should master a solid knowledge of political science. This study was conducted to learn about the intrinsic motivation of learners in Vietnam towards participating in an advanced political science program for future leaders. The study found that learners' intrinsic motivation to participate in a political science program is influenced by their interest in the subject matter, their belief in its relevance to their lives, and their desire to develop critical thinking skills. Additionally, the study identifies a number of factors that can enhance or detract from learners' intrinsic motivation, including teaching methods, course content, and assessment practices. A questionnaire designed with a quantitative method was used to collect data from 91 future leaders who were studying advanced politics at an academy of politics in Vietnam. The results show that they were highly motivated to participate in this program (M = 4.19). Perceived interest or enjoyment (M = 4.58), effort (M = 4.59), perceptions of the program values (M = 4.54), and relatedness (M = 4.54) were encouraging them to learn political science. Moreover, the learners did not experience any pressure or anxiety while taking part in this program (M = 2.46). This study shows that even though most people think political science is dry and mechanical, there are ways to keep learners motivated to learn.

Political science programs play a crucial role in preparing future leaders and managers with the necessary knowledge and skills to succeed in their roles. However, learners' intrinsic motivation to participate in such programs can greatly affect their engagement and success. Educators and policymakers must understand what motivates learners to participate in political science programs.

The leaders of a country play a crucial role in setting its strategic development. Whether serving in private or public organizations, leaders are required to possess a firm knowledge of political science (Galston, 2001). In the Vietnamese context, where the country is led by one Party, a leader's knowledge of political science is even more crucial. To be appointed as a leader, potential leaders or managers must possess the attributes that a leader needs, in addition to having a degree in political science and being equipped with political science knowledge (Sutherland, 2009). However, political science is not always an easy subject for all learners to grasp (Lasswell, 1956). Consequently, their motivation to follow the course should be considered a critical factor.

Although there have been many arguments regarding the low intrinsic motivation of learners to study political science, this field has not received much attention in Vietnam (Brehm & Self, 1989). Studies related to the political science dynamics of learners in the Vietnamese context are difficult to find. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring the intrinsic motivation of learners, particularly future leaders, for a political course in Vietnam. The results of this study will play an essential role in improving the quality of teaching and learning political science in the Vietnamese context and contributing to the literature related to political science.

Motivation is a theoretical construct that explains the initiation, direction, intensity, persistence, and quality of goal-directed behaviors (Deci et al., 1991). Intrinsic motivation occurs when people voluntarily engage in a particular activity because they find it interesting and satisfying. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation occurs when people are externally affected by a sense of urgency or an obligation for their engagement. This study focuses on understanding the intrinsic motivation of learners in a Vietnamese academy of politics. In other words, the study focuses on what drives learners to take a political science course voluntarily because they find it interesting and fulfilling.

This study adapted the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) to measure learners' intrinsic motivation toward learning political science. IMI has been widely used in many extensive studies in the field of motivation (Ryan et al., 1990; Ryan et al., 1991; Deci et al., 1994). There are seven major scales in IMI, which include interest or enjoyment, perceived competence, effort or importance, pressure and tension, perceived choice, value or usefulness, and relatedness. However, for this study, the “perceived choice” scale was excluded since attending a high-level political science course which was not a choice made by the learners. Therefore, this study measures only the remaining six scales of the IMI.

Interest or enjoyment is a dynamic variable that characterizes one's relationship with a particular subject and indicates their psychological state of being attached to that subject over time (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). One's interests evolve from situational interests to personal interests, and they are essential to learners' learning. In addition, interest or enjoyment is strongly associated with academic achievement compared to other motivational constructs. Typically, students' grades at school and university are positively associated with their interest in mathematics (Goetz et al., 2007; Pekrun et al., 2011). Besides, students' interests predict their career aspirations and thus influence their present and future lives (Wigfield et al., 2002). Therefore, the current study attempts to measure the future leaders' interest in the course to know the extent to which learners are motivated to learn the political science course.

According to Deci and Ryan (1985), perceived competence refers to one's perception of their ability to solve problems related to a particular subject. Several studies have examined the relationship between perceived competence and intrinsic motivation towards achieving a specific goal. For instance, Duda et al. (1995) demonstrated the interrelationship between perceived competence and intrinsic motivation. Perceived competence can predict an individual's level of intrinsic motivation toward a goal they want to achieve. Therefore, perceived competence is a crucial and indispensable factor in measuring an individual's intrinsic motivation (Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Selfriz et al., 1992). In this study, measuring perceived competence is necessary to assess their degree of intrinsic motivation towards the political science program.

Effort is the work of a person trying their best, expending a lot of energy to perform a specific task without thinking of giving up. According to Wright (2008), like money, effort is a resource that needs to be used judiciously to produce high results. Most theories of effort consider one's willingness to act and intention to work synonymously. Therefore, many assume that effort and intrinsic motivation are linearly related. In other words, as effort increases, intrinsic motivation increases. Therefore, measuring learners' intrinsic motivation for studying political science in this study is imperative.

Of the six sub-scales measured in this study on intrinsic motivation, "pressure and tension" is the most distinct because it refers to a person's negative emotions (Fino et al., 2021; Saqib & Rehman, 2018). Pressure and tension are two emotions that can have a negative impact on people. Specifically, when experiencing pressure or anxiety, people often have trouble sleeping or have anorexia because they are thinking about the negative outcomes of their work (Morse & Safdar, 2010). However, some studies suggest that these negative emotions can also positively impact learners' intrinsic motivation (Cennamo & Santaló, 2019; Mitchell et al., 2014; Hayasaki & Ryan, 2022). In other words, the fear of poor results can push learners to learn more, which can increase their intrinsic motivation due to these negative emotions. Therefore, this study measures learners' levels of pressure and tension when participating in a political science program.

The values of a program are defined as the benefits that the program brings to learners in many aspects, from academic to practical. Deci et al. (1994) conducted a study and found that task values are essential to one's intrinsic motivation. Similarly, Ciesielkiewicz (2019) asserted that task values are determinants of learners' intrinsic motivation. Participation in this political science program is a mandatory task for the learners in this study in order to be considered for future promotion. Similar to the hypothesis of Song (2021), if the program is not attractive, the learners are still highly motivated to participate because it has critical value. With that hypothesis, program values would be a measured motivator to assess learners' motivation for the political science program.

Relatedness refers to a state of emotions where learners feel they have a stable connection with those around them (Ryan & Deci, 2002). Moreover, Deci and Ryan (2008) have established that relatedness plays an important role in learner motivation. Therefore, the teacher and the institution where the student attends are vital in determining the intrinsic motivation level of the learners. According to Ryan et al. (2005), the higher the quality of the academic staff and the credibility of the institution, the more confident learners will feel, which in turn will increase their motivation to study. In addition to quality teaching, other factors such as care, investment of time, enthusiasm, recognition, and a spirit of cooperation are also believed to be powerful motivators for learners (Brophy, 2010; Blumenfeld et al., 2006). Therefore, a lack of relatedness is considered to be the cause of reduced motivation in learners (Martens & Kirschner, 2004). Relatedness is a must-have aspect used to measure learners' motivation toward the political science program in this current study.

This current study was a descriptive one, designed quantitatively by using a questionnaire to collect data. In terms of the strengths of a quantitative study, it significantly supports the findings with a large number of participants (Bloomfield & Fisher, 2019). This current study promises to provide a general view of the intrinsic motivation of Vietnamese future leaders to engage in a political program, which is mandatory for those who may become leaders in their workplaces in the future.

his study used a convenience sampling technique to recruit participants, specifically through emails provided by the institution in charge of higher-level political science courses. A total of 91 participants responded to the survey in this study, with 53 being male and 38 being female. In terms of age, 11 of the 91 were in their 50s, while 80 were between 35 and 45 years old. As a result, most program learners would spend a long time serving as middle-ranking leaders.

A 35-item questionnaire was used in this study. The questionnaire was designed using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagreeing to strongly agreeing. It was written in Vietnamese, the participants' mother tongue, to avoid any answer ambiguity and misunderstandings. A questionnaire is used to collect data from a large number of participants. The survey questions were discussed and revised. The purpose was to ensure that the questions made clear sense and related to the research topic. In addition, the Scale test, supported by the latest version of SPSS, was used to check the questionnaire's reliability. The survey results of the pilot study, which involved 30 learners in a political science training program, showed that the questionnaire is completely reliable for use in official research (α=.90).

The data collected from the questionnaire were analyzed. The responses were coded with numbers from 1 to 5, where 1 was for the "strongly disagree" response and 5 was for the "strongly agree" response. Then, SPSS was used to check the reliability of the responses. With the use of a Scale test, it was determined that the reliability of the survey was high enough to proceed with further stages of data analysis (α=.91). The data were then imported into SPSS for a series of Descriptive Statistics tests. Based on the mean scores, it could be concluded which intrinsic motivators encouraged the respondents to complete their political programs to become future leaders. In this study, the mean ranges and their interpretations were used to understand the averages (Moidunny, 2009). Table 1 shows the five levels of mean ranges and their interpretations as very low (1.00–1.80), low (1.81–2.60), medium (2.61–3.20), high (3.21–4.20), and very high (4.21–5.00).

Table 1. The Mean Ranges and their Interpretations

According to the results, the learners were highly motivated to pursue the political science program (M = 4.19), which is quite similar to the findings of Adams' study (2018). It shows that learners can be highly motivated to learn about political science if they have a clear learning purpose and recognize the benefits of developing knowledge in this field. The clusters were divided into three different groups based on the level of influence, including low, high, and very high. The motivators at the "very high level of influence" significantly affected the participants' motivation to learn and complete the political course, and they were also significantly affected by their perceived competence. On the other hand, the motivator "pressure or tension" was not a significant factor affecting the learners' desire to learn this course. Table 2 shows the results of the descriptive test on the main clusters of the study.

The results indicated that the participants enjoyed their learning significantly (M = 4.10). Adams (2018) found similar results in a study of student political science dynamics in Washington, USA. Learners in Adams' study showed that they were highly motivated and inspired to study political science when they noticed the positive impact of learning on their lives. Usually, people think political issues are not enjoyable, but the results of this current study show a completely different view on politics (Lasswell, 1956). The different view here has raised a critical question in education that the subject matters or the ways the subject is taught matters. It is pretty unconvincing to say that the academic staff of the course brought the political classes exciting lessons. However, teachers' performance is always one of the top factors determining the quality of teaching and learning and student motivation to learn (Elliott, 2015). It could be interpreted that the quality of lessons, courses, and programs as a whole offered by the teachers positively affected the learners' intrinsic motivation to learn. A descriptive statistics test was run to provide the aforementioned results. Table 3 shows the results related to the first cluster, "interest or enjoyment".

All items in this cluster received very positive responses. Remarkably, no mean score was lower than 4.21, All items in this cluster received very positive responses. Remarkably, no mean score was lower than 4.21, meaning that all items belonged to the "very high level of influence" group. The highest mean score was 4.70 for item 6 "I thought this course was enjoyable," followed by item 1 "I enjoyed learning this course very much" (M = 4.64), item 2 "This course was fun to learn" (M = 4.60), item 4 "This course held my attention" (M = 4.58), item 3 "I thought this course was interesting" (M = 4.57), item 5 "I would describe this course as very interesting" (M = 4.54), and item 7 "While I was learning this course, I was thinking about how much I enjoyed it" (M = 4.40).

The participants seemed very satisfied with their course performance. In other words, they might have achieved what they had expected before participating in the course. In Bunte's study (2019), learners did not really want to develop their skills, similar to the subjects participating in this study. In particular, it was not necessary for them to study in-depth political science anymore when their practical experience was sufficient to solve problems related to politics.

Interestingly, even though their satisfaction with their performance was high, their self-confidence was not positively correlated. It was interpreted that the participants had not set themselves high objectives. Therefore, their goals were still far from what could make them feel confident in themselves (Barber & Taylor, 1990). Besides, the results show a typical characteristic of the Vietnamese people, which is unpretentiousness, modesty, or humility (Van, 2019). When comparing themselves to others, Vietnamese people rarely show off that they are better than anyone. Table 4 shows the results of a descriptive statistics test on the participants' perceived competence.

There are two different levels of influence, "very high" and "high". In "very high" category, there are two items, consisting of item 11 "I was satisfied with my performance in this course" (M = 4.55) and item 13 "This was a course I could do well in" (M = 4.26). The "high" group has four items, including item 8 "I thought I was good at learning this course" (M = 3.95), item 9 "I thought I had done better than others in this course" (M = 3.47), item 10 "After learning this course, I felt competent" (M = 3.77) and item 12 "I was skilled in this course" (M = 3.64).

The participants put much effort into this course, and the results somehow also displayed the reasons for those efforts, which was the importance of the program's completion. The participants undoubtedly perceived the course as essential for them. Its contents could not correctly assess the value of the course, but the program would undoubtedly provide the learners with chances for promotions in the future (Ackah, 2014). Similarly, Keohane (2009) indicated the importance of learning political science since it greatly impacts learners' lives. This program was for future leaders only, so it meant that those who could perform well in the course could prove themselves qualified for a higher position. Table 5 shows the test results for the "effort" cluster.

It can be seen from the test results that the participants did make considerable efforts in learning and completing this political program. All items obtained very high mean scores, and they all belonged to the "very high level of influence" group. Item 16 "It was important to me to do well in this course" got the highest mean score (M = 4.73), followed by item 15 "I tried hard to do well in this course" (M=4.57), item 14 "I put a lot of effort into this course" (M=4.55), and item 17 "I put very much energy into this course" (M=4.51).

It is convincing to say that the participants did not feel much tension or pressure when participating in the political program, even though they were aware of its importance to their future. The current political program is an advanced program about politics. Therefore, the learners had a solid foundation of political knowledge (Sutherland, 2009). Consequently, they felt comfortable participating in the program, even though they may have felt some nervousness. A descriptive statistics test was conducted to measure the average mean scores of the items in the "pressure and tension" cluster. Table 6 shows the test results for pressure and tension.

Different from other clusters, this cluster was perceived not to be a significant factor affecting the learners' motivation to learn the political program (M = 1.20). In other words, the learners felt highly comfortable and motivated while learning this program without tension or pressure. Although item 18 "I felt nervous while learning this course" obtained a high mean score (M = 3.29), learners responded negatively to the others. Mainly, item 19 "I felt tense while learning this course" belonged to the "medium level of influence" group with M = 2.71. Others, such as item 22 "I felt pressured while learning this course" (M =2.18), item 20 "I was unrelaxed in learning this course" (M =2.11), and item 21 "I was anxious while learning this course" (M =2.03), were even categorized into the "low level of influence" group.

The results show that learners highly appreciate the value of this program for their development (M = 4.54). Most of the items in this cluster have mean scores of "very high" (4.21 ≤ M ≤ 5.00). Item 24, "I thought that learning this course was useful for me," has the highest mean score (M = 4.74), followed by item 23, "I thought this course could be of some value to me" (M = 4.67), item 28, "I believed learning this course could be beneficial to me" (M = 4.67), item 25, "I thought this course is important to me" (M = 4.66), item 27, "I thought this course could help me to develop" (M = 4.64), and item 29, "I thought this course was an important event in my life" (M = 4.49). However, learners showed no genuine interest in retaking this course, as indicated by the average mean score of item 26, "I would be willing to learn this course again because it provided me with many values" (M = 3.93).

The value of this course is undeniable, as it directly affects the job promotion of learners. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand the results, which are similar to the hypothesis made by Song (2021). With the degree and knowledge gained in the course, learners can understand political science with remarkable ease. However, people taking this course mostly hold essential positions or responsibilities in their agencies. Therefore, their time is minimal (Buck, 2015). As a matter of course, they were not interested in retaking the course. Table 7 shows the test results for program values.

The relatedness factor was a significant encouragement for learners to attend this advanced political course (M = 4.54). All items received mean scores of very high (4.21 ≤ M ≤ 5.00). Specifically, the highest mean score was for item 37, "I trusted the quality of academic staff ” (M = 4.75), followed by item 38, "I trusted the quality of the institution" (M = 4.70), item 36, "I felt I could trust the instructors of this course" (M = 4.65), item 35, "I did not doubt the instructors of the course" (M = 4.59), item 33, "I felt close to the instructors of the course" (M = 4.54), item 31, "I would like chances to interact with the instructors of this course" (M = 4.51), item 34, "It was likely that the instructors of the course and I could become friends if we had more chances to interact with each other" (M = 4.43), item 30, "I did not feel distant from the instructors of this course" (M = 4.42), and item 32, "I would prefer to talk to the instructors of the course in the future" (M = 4.32).

The results show that high-quality teaching staff and the institution's reputation play an essential role in learners' participation in this advanced political course. The findings align with many previous studies (Ryan et al., 2005; Brophy, 2010; Blumenfeld et al., 2006). This is relatively understandable when considering that the surveyed place is a political school with many years of operation and senior, highly skilled teaching staff. Table 8 shows the results of a descriptive statistics test measuring the average mean scores in the last cluster, "relatedness".

Political science education plays a vital role in the sustainable development of a country. To build a strong nation, leaders need to have a firm grasp of politics. Therefore, teaching and learning political science need more attention. This study shows that learners can be highly motivated to study political science, which was considered an uninteresting field in previous studies. Learners need to understand the role of political science and its impact on their work. Additionally, the teaching staff will play a decisive role in whether or not learners want to participate in political classes and improve their knowledge of political science.

The learners' intrinsic motivation to participate in a political science program is investigated in the study. A quantitative method was used to determine the learners' motivation for studying political science in Vietnam. The data collected from 91 participants through a 38-item questionnaire showed that the learners in this study were highly motivated to study political science. Their motivation stemmed from enjoying the course, recognizing its value to their promotion, and appreciating the quality of the teaching staff. The results indicate that learners highly appreciate the value and relatedness of the program, which positively affects their intrinsic motivation to participate. Moreover, the study found that the quality of the teaching staff and the institution's reputation played an essential role in learners' participation in the program.

These findings have significant implications for political science education. It is important to provide learners with a better understanding of the role and impact of political science on their work to enhance their motivation to participate. Moreover, the teaching staff's quality and the institution's reputation should be considered crucial factors in designing and delivering political science courses. The results of this study provide valuable insights into learners' intrinsic motivation to participate in a political science program, which can help to improve the quality of political science education and ultimately contribute to the sustainable development of the country.

This study successfully investigated the intrinsic motivation of future Vietnamese leaders towards taking a political science course. However, as the study was conducted in a political teaching unit in southwest Vietnam, its results cannot be generalized. Additionally, the use of a quantitative method and a questionnaire as the data collection tool limited the depth of the authors' explanations. Therefore, future research should aim to overcome these weaknesses by collecting data from multiple political science teaching units in different regions of Vietnam and incorporating interviews for more in-depth analysis. Further research on the teaching methods of political science lecturers could also be explored, as maintaining student motivation for political science is a challenging task.