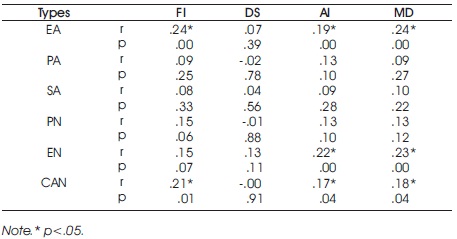

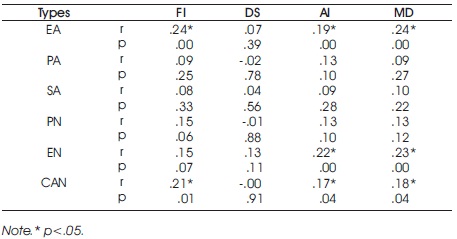

Table 1. Correlation Between Muscle Dysmorphia and Childhood Abuse and Neglect

It was sought to the association between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect in male recreational bodybuilders between 18 and 53 years old (Mage = 28.17 years, SD = 8.66) were recruited from two different gyms in Ankara, Turkey. All participants completed a demographic questionnaire in addition to the Muscle Dysmorphia Inventory and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A significant correlation was found between Emotional Abuse and Functional Impairment (r=.24, p<.05), Appearance Intolerance (r=.19, p<.05), Muscle Dysmorphia (r=.24, p<.05). In addition, there was a significant correlation between Emotional Neglect and Appearance Intolerance (r=.22, p<.05), Muscle Dysmorphia (r=.23, p<.05). Childhood abuse and neglect were correlated with Functional Impairment (r=.21, p<.05), Appearance Intolerance (r=.17, p<.05), and Muscle Dysmorphia (r=.18, p<.05). Consequently, there is a positive correlation between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect in male recreational bodybuilders.

Muscle Dysmorphia (MD), defined as obsessivecompulsive disorder and related disorders, is a subcategory of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), in which the subject thinks that his body structure is too small or insufficiently lean or muscular (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). MD has previously been given various names: reverse anorexia (Pope et al., 1993), adonis complex (Pope et al., 2000), bigorexia (Mosley, 2009). While in some studies MD is classified as BDD (Choi et al., 2002; Pope et al., 1997), some researchers consider it to be an Eating Disorder (ED) (Lamanna et al., 2010; Mosley, 2009). In a systematic review by Dos Santos Filho et al., (2016), diagnostic criteria and nosological classification of muscle dysmorphia were examined. 26% of 34 selected articles postulated it to be a subtype of BDD, while 24% took it as a variant of ED and 9% understood it as part of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders. In 41% of the articles, it was unclear which class MD belongs to, and therefore nosological classification could not be performed. Individuals with MD may enact some compulsive behaviors and thoughts as a result of their obsession about being inadequately muscular. MD can therefore be considered a type of OCD and related disorders.

MD has been reported primarily among males, bodybuilders and anabolic steroid abusers (Ung et al., 2000). Not only psychological factors, but also both socioenvironmental factors and physiological factors can cause MD. While, physiological factors can be considered as body mass, media influences and participation in sports can be considered as socio-environmental factors. In addition, body dissatisfaction, ideal body internalization, self-esteem, body distortion and perfectionism can be considered as psychological factors that contribute to MD (Grieve, 2007). Additionally, MD can be related to childhood abuse and neglect. It has been claimed that childhood experiences of abuse may be related with feelings of disrespect, disgust, or inadequacy of one's body (Smolak, 2011). Childhood abuse and neglect are associated with BDD (Didie et al., 2006) and obsessive‐compulsive symptoms (Lochner, 2002; Mathews et al., 2008). Because MD has similarities in both BDD and OCD, it has been hypothesized that there is an association between childhood abuse and neglect and muscle dysmorphia.

This study was approved by the Gazi University Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2020-086).

The number of participants was determined by power analysis. 145 participants will allow the hypotheses of the present study to be examined at a power of .80, at .05 significance level, and a correlation between emotional abuse and BDD r=.20 - .24 (Didie et al., 2006). A total of 145 male recreational bodybuilders between 18 and 53 years old (Mage = 28.17 years, SD = 8.66) were recruited from two different gyms in Ankara, Turkey. Participants reported an average of 8.14 hours of exercise time per week (SD = 5.52), 2.56 instances of mirror checking (SD = 3.01), 39.75 minutes spent on bodybuilding pages on social media. SD = 0.84 consists of those who have been exercising for 4.54 years (SD = 5.04).

Once informed consent was obtained, participants were asked to complete a series of self-report questionnaires, the Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (MDDI), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and Demographic Questionnaire.

MDDI is a 13-item and 5-likert scale that was developed by Hildebrandt et al., (2004). The drive for size, appearance intolerance, and functional impairment are the three subscales of inventory. Total scores range from 13 to 65 with higher scores reflecting high muscle dysmorphia symptoms. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of MDDI has been demonstrated (Devrim, 2016; Devrim et al., 2018; Devrim & Bilgiç, 2018; Devrim & Bilgiç, 2019). Three subscales of the original inventory were found to be equal to Cronbach's .77 –.85, while the Turkish version of the inventory was found to be equal to Cronbach's .59-.73.

The CTQ is a 28-item, 5-likert scale, self-report questionnaire developed by Bernstein et al. (1994). The CTQ assesses childhood Emotional Abuse (EA), Physical Abuse (PA), Sexual Abuse (SA), Physical Neglect (PN), and Emotional Neglect (EN). The Turkish version of the questionnaire was adapted by Şar et al. (2012). The Cronbach alpha value, which shows the internal consistency of the scale which was found to be 0.93 for the group of all subjects. Correlation coefficient of CTQ total score in the test-retest performed on clinical and non-clinical subjects at two-week intervals was 0.90.

The demographic questionnaire obtained participant information pertaining to age, time devoted to exercise, amount of mirror checking, extent of following bodybuilding related pages on social media, amount of time devoted to pages related to bodybuilding on social media, and duration of bodybuilding.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 for Windows. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of distribution of all continuous variables. For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was set at p =.05.

Correlation between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlation Between Muscle Dysmorphia and Childhood Abuse and Neglect

EA = Emotional Abuse, PA = Physical Abuse, SA = Sexual Abuse, PN = Physical Neglect, EN = Emotional Neglect, CAN = Childhood Abuse and Neglect, FI = Functional Impairment, DS = Drive for Size, AI = Appearance Intolerance, and MD = Muscle Dysmorphia.

It is seen that there was a significant correlation found between EA and FI (r=.24, p<.05), AI (r=.19, p<.05), MD (r=.24, p<.05). In addition, there was a significant correlation between EN and AI (r=.22, p<.05), MD (r=.23, p<.05). CAN was also correlative with FI (r=.21, p<.05), AI (r=.17, p<.05), and MD (r=.18, p<.05).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect in male recreational bodybuilders. The association between MD and childhood abuse and neglect has been extensively researched, and unsurprisingly, the results supported the hypothesis that MD is significantly related with childhood abuse and neglect. An association was reported between MD and childhood abuse and neglect (Didie et al, 2006). In addition, one study reported that BDD patients have a abuse history (Neziroglu et al., 2006).

A significant relationship was identified between emotional abuse, on one hand, and functional impairment, appearance tolerance and MD, on the other. In this study, it was reported that BDD patients endured childhood abuse, including 28% endured emotional abuse, 22% sexual abuse, and 14% physical abuse, in comparison with OCD patients (Neziroglu et al., 2006). A significant association was reported between emotional abuse and body dissatisfaction (Dunkley et al., 2010) and a drive to increase the muscle mass (Brooke & Mussap, 2013). The fact that muscle dysmorphia is directly related to body dissatisfaction places, this finding is parallel with the related literature. Many studies have reported that there is a relationship between emotional abuse and addiction (Carries & Delmonico, 1996; Cuomo et al, 2008). Functional impairment is characterized by symptoms of withdrawal, lack of control and reduction in other activities, as in addiction. The present finding is thus again in parallel with the related literature.

Emotional neglect was associated with both appearance intolerance and MD. A individual with BDD endured childhood abuse and neglect, especially 68.0% enduring emotional neglect, 56.0% emotional abuse, 34.7% physical abuse, 33.3% physical neglect and 28.0% sexual abuse (Didie et al., 2006). It can be thought that emotional neglect is one of the most common type of neglect in BDD. Dunkley and Masheb (2010) indicated that although emotional neglect was not associated with physical dissatisfaction, it was associated with self-criticism in a sample of overweight women diagnosed with binge eating disorder. Actually, self-criticism is one of the main reasons of appearance intolerance. Because individuals with MD may or may not have a real problem about their appearance. The main problem is the thought about appearance.

Parent factor is a significant contribution to child characteristic (Ammerman & Patz, 1996). A child who has been neglected and abused during childhood can learn to neglect and abuse himself/herself in adulthood. MD can be seen as a type of abuse and neglect. Individuals with MD perform excessive physical exercise and this compulsive exercise behavior may cause negative emotions to occur when the exercise program is disrupted, or to stay away from social activities due to the exercise program. It can be thought as a repeated trauma, individuals who are not valued and loved in childhood can learn not to value and love themselves in adulthood. Because, some early maladaptive schemas active in OCD patients (Atalay et al., 2008; Wilhelm et al., 2015). Maladaptive schemas are also associated with parental perception (Harris & Curtin, 2002).

The study concluded that muscle dysmorphia is associated with childhood abuse and neglect in male recreational bodybuilders. The related literature and the findings are mentioned in the discussion section. As a result, there is a positive correlation found between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect in male recreational bodybuilders.

This study suffers from several limitations. Considering that self-report measurement tools may be insufficient on issues such as neglect and abuse, findings can be obtained through case studies in subsequent studies.

The relationship between muscle dysmorphia and childhood abuse and neglect is undoubtedly complex. The current research, however, identified that there is a significant correlation. Since childhood neglect and abuse are a sensitive issue, participants may not have responded openly or there may have been a bias towards forgetting about the past. It can be suggested to be performed with different methods in future studies. Additionally, considering that different variables may affect muscle dysmorphia, studies with regression analysis can provide more detailed information.