Table 1. Demographic Information of the Research Group

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate sportspersonship coaching behaviors from youth athletes' perspective. In this sense, the research group comprised a total of 394 youth athletes,161 girls (40.9%) and 233 boys (59.1%) between the ages of 11-17. Sportspersonship Coaching Behaviors Scale (SCBS) was used as a data collection tool in the study. The analysis of the data obtained in the statistical methods used to define percentages and frequencies was used to determine the distribution of participants' personal information, and to determine whether the data controlled the normal distribution curve and kurtosis values of the data. Additionally the Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used. As a result of the investigation, it was found that the data had a normal distribution. Besides the descriptive statistical models, t-test, ANOVA,Tukey HSD multiple comparison test methods were used in the statistical analysis of the data (α= 0.05). In light of the findings, the highest mean was found for the sub-dimension of the "expectation toward sportsmanship". The subdimension of “winning comes before sportsmanship” has the lowest mean value. In addition, when there is a comparison in terms of genders, the results differ in favour of girls and another difference between the children attending to state school and private school was in favour of children attending private school. As a result, it can be concluded that the sportsmanship coaching behaviors vary depending on gender, age, the duration of the particular sport and type of school.

Many researchers emphasize the importance of sportsmanship coaching in attaining behaviors regarding sportsmanship (Boardley et al., 2008; Boardley & Kavussanu, 2009; Bolter & Kipp, 2018; Bolter & Weiss, 2012, 2013; Côté et al., 2010; Kavussanu, 2018; Shields et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2008). The team climate that will be created by the coaches supports prosocial behaviors of athletes towards sportsmanship and cooperation. For that reason, the climate in which the coach creates is related to how their athletes will orient to prosocial and antisocial behaviors (Boardley & Weiss, 2013). If coaches emphasize sportsmanship, make an effort and teach it, their athletes will exhibit good behaviors in sports as well. However, the athletes of a coach who exhibit bad behaviors may also exhibit behaviors out of sportsmanship (Bolter & Kipp, 2018). Unfortunately, it is a fact that there are trainer behaviors that we do not want to encounter in the sports environment. For example, a female trainer who repeatedly slapped the young athlete of the U-16 team, then did not get up to speed and threw a dustbin to the referee of the match (FotoMac TV, 2020). Although the parent responded to the coach after seeing the match, the match was abandoned st due to events. In another incident, the team of the 1 Amateur Football League insulted male coach athletes through violence in the locker room (Fanatic, 2019). Facing such behavior can certainly have negative effects on the personal development of young athletes. Coaches are the responsible for the positive development of their athletes within the framework of professional ethics. Another case is that not every athlete of the coaches will be elite level persons; conversely, the number of elite athletes will decrease. In this sense, the perspective of the coaches will not only be training performance of athletes. With a holistic perspective, learning should be at the forefront and the development of the psychosocial features of the athletes should also be supported rather than doing with physical capacities and skills. In particular, a holistic education given in the early ages will affect their behaviors in their further ages.

A study carried out in youth sports found that the impact of coaches and spectators in the orientation of athletes towards sportspersonship behaviour which was at the first place (Shields et al., 2007). Similarly Sezen-Balçıkanlı et al. (2018) pointed out that coaches play a functional role on the moral behaviors of athletes and if it is desired to develop prosocial behaviors at athletes and decrease antisocial behaviors, there is a need for coaches to have a good education. It was also pointed out over the importance of coaches in positive youth development and over the effect and importance of mental health of young people (Vella et al., 2016).

Coaches are role models that they play a key role in the character development of athletes. Their behavior, attention to winning, sportsmanship, success, behavior and attitude are carefully observed by their athletes. Of course, the behavior of athletes will be different in a coach who directs his athlete to sportsman behavior and a coach who directs him/her to win at all costs. The viewpoint of sportsmen who have a first-degree effect on the behavioral equipment that will accompany them throughout their sports career is very effective in character development. From this point of view, it is important how athletes observe and evaluate their trainers. The orientation of coaches having a vital importance in the behaviors of children to sportsmanship arouses curiosity, and the studies to reveal these results are important for field studies (in practice / in the field).Increasing non-sportsman behaviors in athletes suggest that coaches are inadequate in this regard. Upon the review of the related literature, it can be seen that there are not enough number of studies conducted on children. In this sense, the purpose of the current study is to evaluate the sports personship coaching behaviors from the perspective of youth athletes.

The participants of the research group were determined with the method of suitable sampling using the principle of volunteer participation and the research group was made up of 161 girls (40.9%) and 233 boys (59.1%), with a total of 394 youth athletes aged between 11 and 17 years. The research group explained in detail about the necessity to evaluate the researcher of the scale and the coach they are working with by the head coaches. The necessary scales were taken from the trainers and parents, and the scales were applied by the researcher half an hour before the training. Detailed information about the research group is given in Table 1.

As the data collection tool of the research, Sports personship Coaching Behaviours Scale was used.

Sportspersonship Coaching Behaviours Scale of which Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Sezen- Balçıkanlı et al. (2018) and was developed by Bolter and Weiss (2012). The scale was made up of 40 items and 8 sub-dimensions. In their study where they investigated the accuracy of the structure obtained in 2013, the researchers arranged questions which were not understandable and so they determined to make a final form, with 6 sub-dimensions and 24 items to express the scale better. (Bolter & Weiss, 2013). At each factor of the structure reached 6 sub-dimensions, there were 4 questions and it is a 5 point Likert type scale. The subdimension of the scale where athletes evaluate the sportspersonship behaviors of the coaches are “Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship”, “Reinforces Good Sportsmanship”, “Punishes Poor Sportsmanship”, “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship”, “Teaches Good Sportsmanship” and “Models Poor Sportsmanship”. The definitions of the components of the theoretical structure in the related study where literature review and focal group interview obtained are as follows.

The sub-dimension of “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” of the Sportspersonship Coaching Behaviors Scale expresses negative behaviors by the coach towards sportsmanship, while other sub-dimensions point out the positive behaviors. The categories of scale were arranged in 5 point Likert type and the positive items measuring the perceptions of adolescent athletes over their coaches regarding sportsmanship behaviors were graded between (1)“Never” and (5)“Quite Frequently”. The negative items in the scale were reversely scored during the analysis. DFA was applied to test the construct validity of the scale.LISREL 8.8 package program was used for this analysis. In order to determine the reliability of the scale, the Cronbach-Alpha reliability coefficient was calculated, and this analysis was applied for the whole scale and for each factor separately. In addition, to provide evidence of the validity of each item, the item's total test correlations were examined and the test was applied between the subgroup item score averages to determine whether each item revealed differences between individuals and the item discrimination in terms of the property to be measured. SPSS 23.0 package program was used for reliability analysis.

In the analysis of the data obtained in the study, percentage and frequency describing statistical methods were used to determine the distributions of personal information of the participants; skewness and kurtosis values of the data were controlled to determine whether the data show normal distribution; and additionally, Kolmorogov Smirnov test was applied. At a result of the investigations, it was determined that the data had a normal distribution. Besides, the descriptive statistical models, t-test, Anova, Tukey HSD multiple comparison tests were also used in the statistical analysis of the date (α=0.05). In the original scale, Cronbach alpha values are as follows.The Cronbach's alpha value for the entire scale is .85, the value for the first sub-dimension (Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship) is .70, the value for the second sub-dimension (Punishes Poor Sportsmanship) is .77, the value for the third sub-dimension (Teaches Good Sportsmanship) is .77,It was found that the value of fourth sub-dimension (Reinforces Sportsmanship) was .82, the value of the fifth sub-dimension (Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship) was .84 and the value of the last subdimension (Models for Sportsmanship:) was .70.Cronbach alpha values for this study is given as follows: the value of the first sub-dimension .70; the second sub-dimension is .75; the third sub-scale value was .65, the fourth sub-scale value was .75, the fifth sub-scale value was .74 and the last sub-scale value was .70.The total internal consistency of the scale is .72.

As given in Table 1, 59.1% of the participants included in the research are boys and 40.9% are girls. As for age groups, the highest percentage is in the age group of 13 (17.3%). Also, 73.9% of the youth athletes have their education at state schools while 26.1% attend private schools. The rate of athletes who play sports in a club as an athlete for 1 year comprises 23.9% and this rate is equal to 18.8% children who play a sport as a club member for 6 years.

While the rate of team sports is 50.5%, it is 49.5% for the group of individual athletes. While 34% of the children are working with the same coach for 1 year, 10.9% of them pointed out that they work with the same coach for 6 years. Table 2. Distribution of Sub-Dimension Scores of the Scale

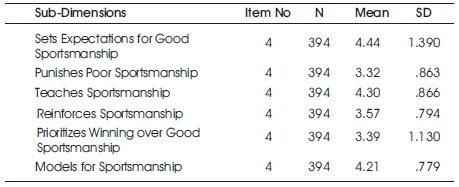

Table 2. Distribution of Sub-Dimension Scores of the Scale

The mean scores of the participants obtained from the subdimensions in the sportsmanship coaching behaviour scale are given in Table 2. Accordingly, the highest mean score is at the sub-dimension of “Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship” with 4.44 while the lowest one is at the sub-dimension of “Punishes Poor Sportsmanship” (x=3.32).

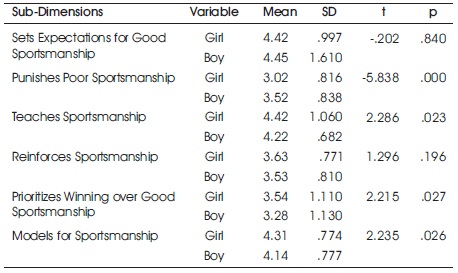

The mean scores of the participants obtained from the subdimensions in the sportsmanship coaching behaviour scale in terms of gender variable are given in Table 3. Depending on the t-test scores based on gender variable, a significant difference was found in the sub-dimensions of “Punishes Poor Sportsmanship”, “Teaches Sportsmanship”, “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” and “Models for Sportsmanship” between sub-dimensions (p<0.05).

Table 3. Distribution of Scale Scores in Terms of Gender Variable

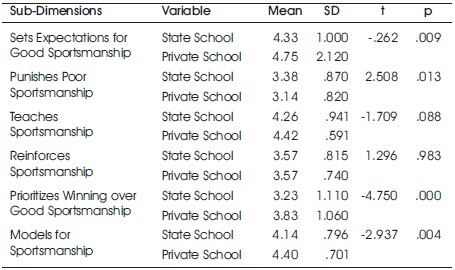

The mean scores of the participants obtained from the subdimensions in the sportsmanship coaching behaviour scale in terms of school type variable are given in Table 4. Depending on the t-test scores based on school type variable, a significant difference was found in the subdimensions of “Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship”, “Punishes Poor Sportsmanship”, “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” and “Models for Sportsmanship” between sub-dimensions (p<0.05).

Table 4. Distribution of Scale Scores in Terms of School Type Variable

The mean scores of the research group obtained from the sub-dimensions in the sportsmanship coaching behaviour scale in terms of age variable are given in Table 6. Depending on the Anova Test scores based on age variable, a significant difference was found between all sub-dimensions (p<0.05). According to Tukey, HSD multiple comparison test results were made to determine between which groups had a significant differences, the significant difference was found in the sub-dimension of “Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship” and in favour to 12- 16 and 12-17 age groups and 12 age group participants; In the sub-dimension of “Punishes Poor Sportsmanship”, there was a significant difference resulted from the participants of 11-17 age group and those of 17 age group; the significant difference was found in the subdimension of “Teaches Sportsmanship” and in favour to the participants of 13-16 and 13-17 age groups and the participants of 13 age group; the significant difference was found in the sub-dimension of “Reinforces Sportsmanship” and in favour to the participants of 12-14 and the participants of 14 age group; the significant difference was found in the sub-dimension of “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” and in favour to the participants of 11-12, 11-16 and 11-17 age groups and the participants of 12 age group; the significant difference was found in the sub-dimension of “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” and in favour to the participants of 11-12, 11-16 and 11-17 age groups and the participants of 12 age group; and it is likely to say that the significant differences resulted from the low scores obtained by the participants in the sub-dimension of “Models for Sportsmanship” and in favour to the participants of 11-16, 12-16 and 13-17 age groups and the participants of 16 age group.

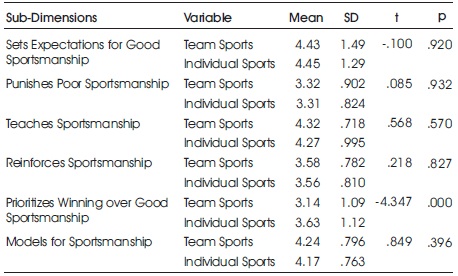

Table 5. Distribution of Scale Scores in Terms of Sport Branch Variable

The mean scores of the sub-dimensions in the sportsmanship coaching behavior scale in terms of sportsmanship duration variable are given in Table 7. Depending on the Anova test scores based on sportsmanship duration variable, a significant difference was found in the sub-dimension of “Teaches Sportsmanship”, “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” and “Models for Sportsmanship” between sub-dimensions (p<0.05). According to Tukey, HSD multiple comparison test results that was made to determine between which groups had a significant difference, it was found that the significant difference resulted from the participants who had been an athlete at a club for 2 and 6 years and from those who were at club for two years in the sub-dimension of “Teaches Sportsmanship”. In the sub-dimension of “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sports manship”, it was found that there was a significant difference resulting an athletes from 6 years and over and that there was a significant difference resulting from the athletes playing a sport in a club for 6 years and over in the sub-dimension of “Models for Sportsmanship”.

In line with the findings obtained in the Sportspersonship Coaching Behaviors Scale, it is likely to see that the subdimension of “Sets Expectations for Good Sportsmanship” has the highest mean. The lower mean is in the “Prioritizes Winning over Good Sportsmanship” (Table 2). When the findings obtained as the fact that the coaches set expectations for good sportsmanship on their athletes, teach sportsmanship, model for sportsmanship are taken into consideration, it is likely to see that winning is prioritized over sportsmanship in completion in the application phase where winning and losing is in question, as well as it is satisfying. This case brings many troubles. The preference of the athletes in some dilemmatic conditions encountered at sport changes in line with the wish of the coach and the sense of “win at all cost” takes its place when winning comes before sportsmanship. As the real purpose of the coach is to win here, there must not be the necessity of doing it fairly. Otherwise, as Reid (1998) pointed out, when the sense of “win at all cost” is regarded as a general perception, the meaning of the concept of success changes. This is called as “success” even if the athletes win it in an unsuitable way. Because “success” is defined analytically. In other words, the winner athlete or team is the one to reach the finish line in the first place, to jump the highest point, to throw the furthest point, in short, the one who obtains the best place. Even if some unethical behaviors are observed in the process of reaching the analytical success, they are ignored (Reid, 1998). The characteristic feature of the current sport is to put physical, mental and emotional pressure upon the opponent. “Playing” is pushed backward; in this way, the chance to win is enhanced. (Lumpkin et. al, 2005 ). However, the eyes of the coaches must be on the child not on the ball (Shields & Bredemeier, 1995). Educators can instruct the participants that success in sports is less important compared to the sense of honesty of the child. (Covrig, 1996). This is because those who are aiming only for success can use the conditions where such things as harming the opponent, seeing them as an enemy, cheating is possible and focus only on winning (Boxill, 2002). As the idea of focusing only on winning prevents the sense of morality, educators should try to make an emphasis on such benefits of sports as friendship, exercise, development. They must give importance on the development of the players, their contribution to the team and their involvement. Despite this, some coaches and parents could ignore it. Coaches shout at children in spite of their young ages and lead them to such negative behaviors as arguing with the referee. This case clearly shows the direction in which young people will go in sports (Brennan, 2005). The first purpose of the coaches must not be to train the individuals who have lost for the sake of success but for one who complete their character education by means of sport (Sezen & Yıldıran, 2007). Upon the review of sportspersonship coaching behaviors in terms of gender variable, it was found that findings were significant in favour to girls (Table 3). Sportspersonship coaching behaviors is higher at girls compared to boys. Another finding is that sportspersonship coaching behaviors between the students attending a state school and a private school is in favour to the ones who attending a private school (Table 4). Sport branches were categorized as individual and team sports. The results obtained show that the coaches of individual team prioritize winning over sportsmanship (Table 5). For the sportsmanship duration and age variables, as the age and duration of playing sport increases, sportspersonship coaching behavior decreases (Table 6 and 7). As a matter of fact, these results support the related literature. In a study by Kalliopuska (1987), it was found that as the duration of playing baseball of the athlete lengthens, they show lesssensibility which is an element of empathy. Similarly, another study by Pilz (1995) pointed out that when the duration of active sportsmanship of the athlete lengthens, they regard violations, playing with foul and winning in an unfair way is considered as an “intelligent tactic”. Having a great effect on their athletes in orienting them to sportspersonship behaviour, coaches must set a role model by acting in this way and supporting not only their physical development but also holistic development. As much as the effect of sport which is of vital importance in the character development of athletes comprises a formation that must be examined seriously particularly at young ages.

Not all athletes will be elite athletes, on the contrary, the number of elite athletes will be low. In this sense, the perspective of coaches should not only be for training the performance of athletes.“Learning” should be at the forefront of athletes with a multi-dimensional perspective. The development of psycho social features should be supported not only by increasing the physical capacity and skills of athletes. Coaches should focus on the skill development of their athletes during training or playing the sport and seeing the effort of every athlete in their team and ensuring the cooperation among players. In addition, young athletes should focus on value learning and skill development. Because ethical behaviors are not innate behaviors and are learned later. No one can be well characterized at once, but it has this capacity from birth and this must be developed through education. Coaches must be trained in a way that they are equipped to support the holistic development of children. In the process of coaching, they should contribute to the awareness process for sportsmanship while doing it for everyone and at every level, without considering the duration in the sport and without making any discrimination between the genders. If there is a fairly won game, its value should be appreciated and coaches must act in their approaches to their athletes with this perspective. The belief of the coaches in this case comprises an important point here. It must be known by the coach in the first place that sports personship comes before winning. As a conclusion, the sports personship coaching behaviors have a vital effect on the athletes to exhibit sportsmanship behaviors.