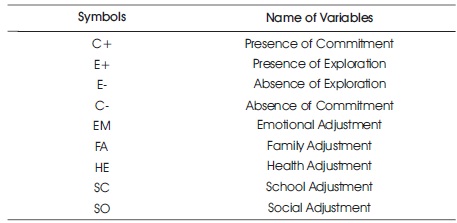

Table 1. List of Variables Used in the Study

Identity formation has been a keen area of interest for researchers and it involves several physiological, cognitive, biological, emotional, and hormonal changes often influenced by the adolescent's social environment. Adler conceptualized the notion that birth order of a person can leave an indelible impression on an individual's style of life. Birth order has a profound effect on how an adolescent is perceived by their family and how a person relates to the amount of responsibility, independence, and freedom he or she has been given. Based on this ideology, this paper attempts to understand the influence of birth order on the identity formation of middle adolescents. The exploratory study undertakes a purposive sampling of 158 respondents (79 males and 79 females). Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (EIPQ) and Global Adjustment Inventory were the tools used for data collection. Correlation analysis indicated significant relationship between identity and various dimensions of adjustment. t-ratios were applied to study gender differences, though no significant results were found. Also, one-way ANOVA was applied to study between group differences. However, findings suggested no significant differences between the first and third born individuals for their identity formation process.

The person we become is partly defined by the order in which we come in our family, as it plays a substantial role in the development of our thoughts, ideas, and perceptions. Identity formation is a key aspect of adolescence as a combination of physical, cognitive, and social changes occur during that time (Erikson, 1968). Adolescents articulate descriptions about themselves based on prior definitions, giving equal importance to their current preferences in values, interests, and social expectations. This leads to a more or less coherent unique whole identity, that not only provides the young adult with a sense of continuity with the past but also shows them a pathway to the future. It has been observed that sibling hierarchy has a profound effect on one's personality and influences everything ranging from career choices individuals make to the people they fall in love with (Adler, 1964).

There have been several studies describing the impact of birth order on individual's personality and relating it with their adjustment levels. First-borns are generally more responsible, ambitious, organized, and academically successful, which makes them more conscientious than later borns. On the contrary, later-borns are found to be more adventurous and unconventional though less neurotic than first-borns. According to McHale and Crouter (2005), children and adolescents spend more time with their siblings than with their parents or peers outside of school and so they serve as confidants, companions, and role models throughout childhood and adolescence. As a result, siblings play a key role in adolescents' identity formation by influencing their opinions and choices in life. Adler describes the secondborn child as someone who has a "pacemaker". Since there is always someone who was there first, this child may grow to be more competitive, rebellious, and consistent in attempting to be best. Middle children may struggle with figuring out their place in the family and, later in the world.

During the transitional phase of adolescence, which is interspersed between the morality learned by the child, and the ethics to be developed by the adult, the adolescent makes a series of ever narrowing selections of personal, occupational, sexual, and ideological commitments which may be governed by his/her birth order. Jha, Dwivedi, and Singh (2012) suggested that there were no significant differences between the levels of adjustment of first and second borns. Erikson (1968) highlighted the central role of identity development in facilitating personal adjustment and well-being. Individuals for whom identity synthesis predominates over identity confusion are likely to be better adjusted than those for whom the opposite is true. Based on his pioneering work on identity and psychosocial development, Marcia (1966, 1980) extended the concept of ego identity and conceptualized the formation of identity along two dimensions: exploration and commitment. Exploration refers to the active questioning and consideration of various alternatives. Commitment pertains to choosing from among the alternatives one has explored. During this process, adolescents either explore or commit to particular career choices, ideologies, and interpersonal styles. This lays down the foundations of four identity statuses- Achievement, Moratorium, Foreclosure, and Diffusion (Marcia, 1966).

The review of literature highlights that individuals who have gone through a period of exploration or identity crisis and have made identity defining commitments, are known as identity achieved individuals (Santrock, 2007; Arnett, 2009). These people can deal with stressful situations and usually attain high scores on measures of autonomy. Nuttall, Nuttall, Polit, and Hunter (1976) reported that firstborn girls had better attainment than the later-born girls in the academic achievement domain. However, Edwards and Thacker (1979) discovered no association between birth order and grade point average. Besides, Hauser and Sewell (1985) also reported no significant birth order effect on academic achievement when other confounding variables were controlled.

Moratorium is a state that not only marks little real commitment to an ideology or occupation, but is also a state of experimentation. They are immensely selfreflective, but usually remain in a state of eternal conflict. Foreclosed individuals are the “culture bearers”, who maintain commitments based on the values and choices of their parents and significant others, rather than the individual himself. This phase encompasses no exploration but a definite sense of commitment. According to Meeus Iedema, Helsen, and Vollebergh (1999), they adopt standards from the surrounding environment without making the effort to solve problems, choose goals, values, roles or beliefs concerning the surrounding world. Diffused individuals are known as “apathetic wanderers”. People falling in this category often show an indifferent attitude towards life; unable to make identity-defining commitments. These individuals may or may not have explored earlier but are certainly not ready to make any promises as far as their vocational or career goals are concerned.

The order in which a person is born in the family communicates a sense of acceptance to the adolescent that allows him/her to be free to try on new roles and to begin to make independent decisions while still maintaining a sense of comfort in the knowledge that the parents are there to support this behavior. In spite of being raised in a similar environment and sharing the same genetic pool, adolescents tend to differ in their personalities, familial sentiments, and other characteristic traits. Adolescents face a lot of issues pertaining to autonomy, career choices, familial conflicts, and peer influences in life. These problems can be understood as a function of the way they are treated owing to the order in which they are born in their family. Thus, birth order continues to have a strong presence in understanding identity formation of adolescents as a whole.

The present study focuses on identity formation and how it is influenced by the birth order of adolescents in the Indian context. Identity formation plays a pivotal role in an adolescent's life and to a great extent influences the manner in which he/she deals with a variety of issues. During adolescence, individuals are in a quest for personal identity and a sense of self. They continue to introspect about their ideologies, values, and goals. Throughout this process of exploration and commitment, some adolescents fail to establish an understanding of who they are and who they wish to be. This unresolved crisis may have negative implications on health, family, school, and social life. It has also been observed that the order in which the person is born has a considerable impact on the identity process with a perpetual influence on person's beliefs, interactions, and experiences. While there has been an extensive literature review on the relationship between personality and birth order, the association between birth order and identity has not been explored in great detail. Therefore, this paper attempts to extend the theoretical rationale to encompass birth order as a fundamental aspect in the formation of identity.

A purposive sampling of 158 middle adolescents (79 males and 79 females) in the age group of 14-16 years with mean age 14.76 years and standard deviation of 0.74 were chosen for the study. This study undertakes birth order as the independent variable, identity and adjustment as dependent variables. Age was kept constant. Table 1 highlights the symbols used for defining various variables in the present study.

Table 1. List of Variables Used in the Study

One of the scales used in this study was Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (EIPQ) by Balistreri, Busch- Rossnagel, and Geisinger (1995). Although this questionnaire included 32 items, 28 items were used for the present study (4 items related to dating were omitted). These items measure the degree of exploration and commitment in eight areas: occupation, religion, politics, values, family, friendship, dating, and sex roles. For the 32- item version, the internal consistency estimates (coefficients alpha) of the commitment and exploration scores were 0.80 and 0.86, respectively. The Kappa coefficient value calculated by five expert raters for all 32 items was 0.76. This indicates statistically significant agreement among the experts regarding the assigned dimension of the items. The reliability coefficients are r(40)= 0.90, p<.01 for commitment and r(40)= 0.76, p<.01 for exploration.

Global Adjustment Scale (GAS) developed by Psy-Com Services (1994) was used to measure how well the student understands and has learned to live with his/her feelings and emotions in the physical and social environment. For the present study, the student form (Form S) has been used that obtains responses pertaining to Emotional Adjustment (EM), Family Adjustment (FA), Health Adjustment (HE), School Adjustment (SA) and Social Adjustment (SO). Due to the reverse scoring of items pertaining to various dimensions of adjustment, low scores indicate better adjustment in the respective dimensions. The reliability of GAS (Form S) was calculated as split half reliability and test-retest reliability coefficients with one-month interval. Split half reliability calculated using Spearman-Brown formula indicated reliability of 0.79 for emotional adjustment, 0.69 for family adjustment, 0.79 for health adjustment, 0.78 for school adjustment, and 0.83 for social adjustment. The test-retest reliability scores came out to be 0.74, 0.65, 0.69, 0.72, and 0.82 for emotional adjustment, family adjustment, health adjustment, school adjustment, and social adjustment, respectively.

Descriptive statistical measures of mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and correlation were used to analyze the data for males and females, respectively. Inferential measures of t-ratios and ANOVA were used to interpret the gender differences and to study the impact of birth order on identity and adjustment, respectively.

The results indicate that the values of skewness and kurtosis (for male and female, respectively) lie between -1s and +1s. Since the data entirely falls on the Normal Probability Curve, it indicates that the sample truly represents the population under consideration.

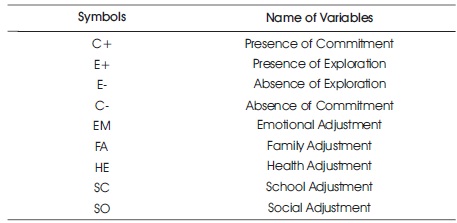

Table 2 reveals the mean values, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis for exploration and commitment as well as adjustment for male adolescents. Identity-related variables reflect mean and standard deviations as C+ (M = 37.23; SD = 5.00), E+ (M = 34.10; SD = 5.83), E- (M = 24.08; SD = 5.31) and C- (M = 17.48; SD = 4.24). Further, variables pertaining to adjustment indicate mean and standard deviation values as EM (M = 19.28; SD = 6.96), FA (M = 12.59; SD = 8.94), HE (M = 11.40; SD = 5.15), SC (M = 15.19; SD = 6.58), and SO (M = 19.63; SD = 8.95).

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviation, Skewness, and Kurtosis of Male Adolescents for the Variables under Study (n=79)

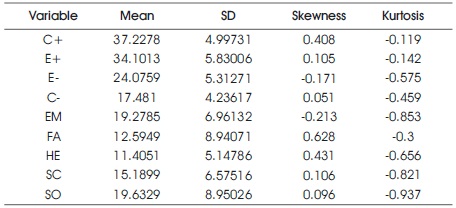

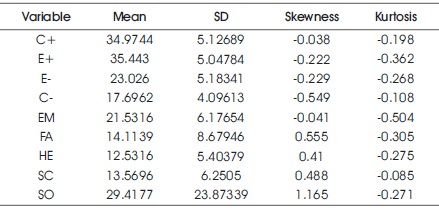

Table 3 reveals the mean values, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis for exploration and commitment as well as adjustment for female adolescents. Identityrelated variables reflect mean and standard deviations as C+ (M = 34.97; SD = 5.13), E+ (M = 35.44; SD = 5.05), E- (M = 23.03; SD = 5.18), and C- (M = 17.70; SD = 4.10). Further, variables pertaining to adjustment indicate mean and standard deviation values as EM (M = 21.53; SD = 6.18), FA (M = 14.11; SD = 8.68), HE (M = 12.53; SD = 5.40), SC (M = 13.57; SD = 6.25), and SO (M = 29.42; SD = 23.87).

Table 3. Mean, Standard Deviation, Skewness, and Kurtosis of Female Adolescents for the Variables under Study (n=79)

Results indicate that male adolescents who lack exploration are found to be significantly positively correlated with emotional adjustment (r = -.26, p<.05) and family adjustment (r = -.30, p<.01) levels. However, lack of commitment was significantly negatively correlated with emotional adjustment (r = 0.28, p<0.05), family adjustment (r = 0.34, p< 0.01), health adjustment (0.26, p<.01), and school adjustment (r =.34, p<.01) (as shown in Table 4).

Females who are high on commitment are found to be significantly positively correlated with school adjustment (r =-.24, p<.05) and social adjustment levels (r= -.28, p<.05) (as shown in Table 5). However, females with low exploration were found to be significantly positively correlated with social adjustment (r= -.26, p<.05). Thus, the first hypothesis was partially supported since evidence indicated that achievement and foreclosure statuses are associated with levels of adjustment.

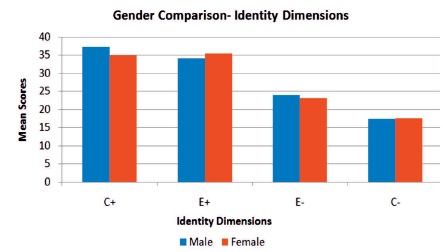

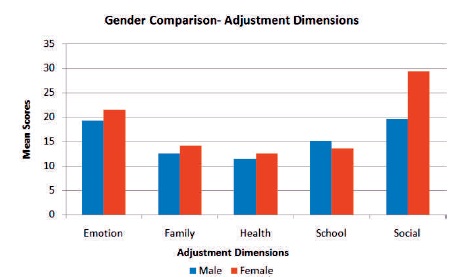

The perusal of the study indicates that there are no significant gender differences in identity formation and level of adjustment of middle adolescents. Thus, the second hypothesis was rejected. However, as shown in Table 6, when compared in terms of mean values, males score higher on commitment (M = 37.23, SD = 5.00) but lower on exploration (M = 34.10, SD = 5.83) dimension of identity. On the other hand, females rank lower on commitment (M = 34.95, SD = 5.10) and higher on exploration levels (M = 35.44, SD = 5.05). Overall, females tend to be better adapted than males as they score higher in almost all the domains of emotional adjustment (M = 21.53, SD = 6.18), family adjustment (M = 14.11, SD= 8.68), health adjustment (M = 12.53, SD = 5.40), and social adjustment (M = 29.42, SD = 23.87), except school adjustment (M = 13.57, SD = 6.25). Comparison on the basis of gender is displayed in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Comparison of Mean on the Dimensions of Identity based on Gender Differences

Figure 2. Comparison of Mean on the Dimensions of Adjustment based on Gender Differences

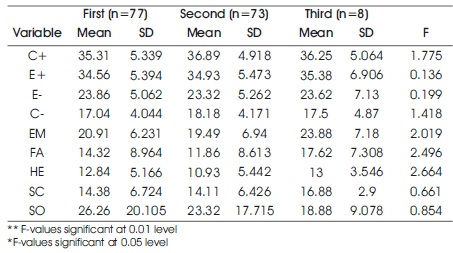

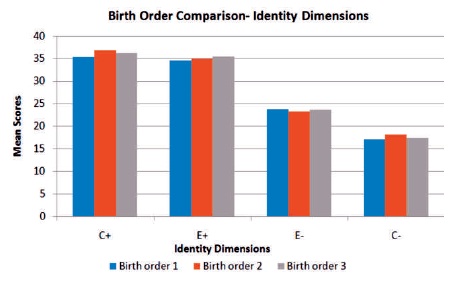

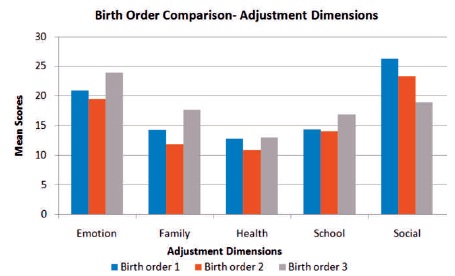

ANOVA was used to compare the mean scores of identity domains and adjustment across different birth orders. An overview of the scores indicate that high levels of commitment are found in second-borns (M = 36.89, SD = 4.92) followed by the third-borns (M = 36.25, SD = 5.06) and subsequently lowest in the first-borns (M = 35.31, SD = 5.34). A similar trend is observed for lack of commitment as well. Third-borns are found to be highest on exploration (M = 35.38, SD = 6.91) while first-borns score lowest in this domain (M = 34.56, SD = 5.39). Very minute differences are observed in the levels of presence (M = 34.56, SD = 5.39; M = 34.93, SD = 5.47; M =35.38, SD = 6.91) and absence of exploration M = 23.86, SD = 5.06; M = 23.32, SD = 5.26; M = 23.62, SD = 7.13) between the first, second or third-borns. The data also signifies that thirdborns have highest levels of emotional, family, health, and school adjustment. On the contrary, first-borns are found to be more adjusted at the social level than the second and third-borns. However, with an alpha level of 0.05, birth order effect on identity and adjustment is not statistically significant at all (as shown in Table 7). Thus, the third hypothesis was also not supported. Comparison on the basis of birth order is displayed in Figures 3 and 4.

Table 7. Analysis of Variance for Identity and Adjustment

Figure 3. Comparison of Mean on the Dimensions of Identity based on Birth Order

Figure 4. Comparison of Mean on the Dimensions of Adjustment based on Birth Order

This research paper attempts to study the impact of birth order on identity domains and adjustment levels in adolescents. Adolescence is a transitional phase between childhood and full adulthood, which is a critical developmental period shaped by individual, familial, social, and historical circumstances, where both disorientation and discovery can transpire. It can bring up issues of independence and self-identity; many adolescents and their peers face tough choices regarding schoolwork, sexuality, drugs, alcohol, and social life. Peer groups, romantic interests, and appearance tend to naturally increase in importance for some time during a teen's journey towards adulthood. The order in which a person is born in his/her family may have a significant impact on identity formation. This can be extended to see the further implications on an individual's adjustment levels in the different spheres of life. Research on the influence of birth order pertaining to identity development has been very minimal, which allows an area of study that still needs to be explored.

The first objective was to understand the relationship between identity domains and adjustment levels. Males who are high on commitment, but lack exploration fall under the category of foreclosed identity status. These individuals mimic the identities of their parents or other major authority figure. They have not gone through an exploration process and are committed according to their parental choices, goals, and values (Schiedel & Marcia, 1985). Also, they can resolve general problems such as learning to accept and express; and can also control their emotions effectively (Table 4). Usually, they are expected to live up to the expectations of their family and share healthy relationships with their loved ones. On the other hand, people who rank low on commitment can face health and well-being issues and also have a negative impact on academic performance. Females who have gone through a phase of exploration as well as commitment (Table 5), that fall under the category of Achieved may be welladjusted in their school environment and maintain cordial relationships with friends and society at large. Females who show greater extent of commitment, but not exploration, fall under the foreclosure identity status. This status has also been found to be associated with psychological well-being, adjustment and emotional stability by researchers like Crocetti, Rubini, Luyckx, and Meeus (2008); Kroger (2007).

The second objective examines the gender differences in identity domains and adjustment levels. Although no significant differences were found between the two (Table 6), males might show a greater tendency to choose from the choices they have scrutinized, making firm and unwavering decisions regarding beliefs and occupation (Luyckx, Goossens, & Soenens 2006). On the contrary, females dynamically search for the solutions of several issues, such as fluctuating goals, roles, and opinions about the society before making commitments, indicating high degree of exploration, but low level of commitment. Archer (1989) suggested that males were significantly more likely to be foreclosed (high commitment, low exploration) whereas females were more likely to be in the moratorium (low commitment, high exploration) domain. It can also be inferred, that females show a more positive attitude towards society, better friendship skills and stronger relationships with parents. They also possess greater ability to understand and regulate their emotional state as compared to males. However, males are better adjusted in the school environment and can resolve issues related to bullying, peer pressure and academic performance. Suthar (2015) also found that females were higher on emotional and social adjustment as compared to males.

The third objective aimed to understand the impact of birth order on identity and adjustment, however, no such significant impact was found. From Table 7, the overall trend indicates that lowest level of commitment was found in first-born, followed by the third-born and subsequently highest in second-born. Kluger (2011) suggests that first-born children help mentor and tutor their younger siblings as they come along. Not only do the younger siblings learn things from their older siblings, but the older siblings learn how to become caretakers. In case of middle-borns, this could be since elder siblings serve as role models who may either facilitate their identity formation or lead to role confusion. Middle children usually look at their older sibling and feel like they are in a race with the first-born to take the first-born child's privileged position away (Kalkan, 2008). Since third-borns are found to be highest on the dimension of exploration, we can infer that they would either fall in the Achieved or Moratorium Identity Statuses. Pertaining to adjustment, the last born child is found to be emotionally stable, maintaining good interpersonal relationships with a greater ability to ensure his/her well-being and resolve school-related issues. On the contrary, first-borns are found to be the lowest on exploration they may either fall in diffused or foreclosed identity statuses. Also, first-borns were found to be more empathetic, easy going, adventurous, popular, and sociable.

First-borns are likely to form diffused or foreclosed identities whereas third-borns have a greater tendency to form moratorium or achieved identities. However, identity status pertaining to middle-born children remains unclear allowing another area of study that needs to be explored. Researchers view the turbulence during adolescence not as an inevitable component of the developmental stage, but as a function of the various cognitive processes that occur during development. Thus, findings of the study would aid the counselling process for adolescents struggling with identity issues as well as facing adjustment problems.

The findings of this study contribute to strengthen the conceptual framework around birth order and identity and thereby substantiate existing research evidences. An insight into the link between identity and adjustment can help counsellors set guidelines to solve psycho-emotional problems and develop interventions. Moreover, it can facilitate a better understanding of one's self and therefore strike a balance between his/her desires and the capacity to fulfil them.

The findings of the present study suggest that similar studies comprising of a more diverse sample of individuals from different socio-economic strata and cultural backgrounds may reveal a more comprehensive picture. Studies can also be conducted across different phases of adolescence to ascertain the role of birth order in identity formation. Cross-cultural studies among other age groups with the same variables are suggested. The relationship between identity formation and other variables such as self-esteem, attachment and environmental context can also be investigated. Also, a comparative analysis can be drawn to highlight variations in identity development and adjustment levels among the first-born and the only born (single child).

As authors, we wish to express our gratitude to DPS Indirapuram, DAV and Bal Bharti School, Pitampura for allowing us to conduct research in their premises. Our sincere thanks to participants for sparing their time and giving valuable contributions to the study.