The first hours after birth are a critical period to develop the mother-newborn attachment and to reduce the anxiety related to the baby. Cesarean section and subsequent separation of mother and baby can increase the disorders resulted from this separation. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of early skin to skin contact on maternal attachment behaviors in neonates after cesarean section in a hospital in South East of Iran. This is a randomized controlled trial study, which was done on 80 mothers and newborns after cesarean section with spinal anesthesia in a hospital in South East of Iran operating room. The research samples were assigned into two groups including; skin to skin contact group and the routine care group. In the intervention group immediately after the birth, the baby was placed in prone position on the mother's chest, and in the routine care group, the baby was placed under radiant warmer just immediately after the birth. Afterward, the data were gathered by using checklists of Avant mother attachment behaviors. Data analysis was done by SPSS version 22. The results showed that there is no difference between both groups in the demographic variables. A significant difference was found between both groups in the mean scores of emotional behaviors (p<0/0001) and caretaking behaviors (p<0/0001). However, no significant difference was found between the two groups in the close contact behaviors (p=0.22). According to the results of this study, mothers who had skin-to-skin contact with their baby showed more emotional and caring behaviors. Therefore, in cesarean sections, due to the problems with starting breastfeeding as well as long separation between mother and baby after surgery, skin-toskin contact is recommended after birth as an inexpensive and easy method.

The Cesarean section (C-section) rate has steadily increased over the past few decades. Different studies on the subject indicate an increased rate of 26% to 66/5%, and 87% in some private clinics in Iran (Davari, Maracy, Ghorashi, & Mokhtari, 2012). Separation of the mother and baby after birth is an accepted tradition nowadays (Phillips, 2013). While keeping mothers and babies together during the first hours after birth has its own benefits, it is this contact that causes the mother-baby attachment and reduces the stress and anxiety of the baby (de Alba-Romero et al., 2014; Karimi, Tara, Khadivzadeh, Sherbaf, & Reza, 2013). Childbirth is a stressful experience for mothers, and in case of Cesarean section, this stress and anxiety, as well as the postnatal disorders, increased due to the separation between the mother and her newborn (Keshavarz, Norozi, Sayyed & Haghani, 2011). This separation may also cause other side effects, such as Hypothermia, bradycardia, and hypoglycemia in neonates (de Alba-Romero et al., 2014; Phillips, 2013).

It is in the first hours of extra uterine life that the baby meets his/her parents for the first time, and a family is formed (Phillips, 2013). The communication between the parents and their newborn improves the quality of the parental role and the parents' sense of competence (Borimnejad, Mehrnush, Seyed-Fatemi, & Haghani, 2012). One of the recommended intervention strategies to care for newborns is skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby, which is suggested by the family-based approach of the treatment team (Moore & Anderson, 2007).

Skin-to-skin contact Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) method was suggested for the first time by Dr. Edgar Rey in Bogota, Colombia, in 1978 as a way to compensate for national resources in hospitals, which take care of Low Birth Weight (LBW) newborns (Belizan, 2011). In this method, the baby, who is naked except for a diaper, is placed in an upright position against the mother's bare chest and his or her back is covered by a piece of cloth (Moore & Anderson, 2007). Studies indicate that this method has significant physiologic, cognitive, and emotional benefits for preterm newborns (Nyqvist et al., 2010).

In general, even if this contact does not compensate for the negative impact of the mother-baby separation, it surely accelerates the neurobehavioral maturation. In a study on the effect of skin-to-skin contact on the neurobehavioral responses of the newborns, Ferber and Makhoul (2004) concluded that the babies who received skin contact had long and quiet sleep state and good postures (Ferber & Makhoul, 2004).

Mothers who have had a skin-skin contact with their newborns after birth are more satisfied and feel more selfconfident and competent in childcare and meet their baby's needs more quickly in comparison to those mothers who have been separated from their babies after birth (Moore & Anderson, 2007; Velandia, Matthisen, Uvnäs- Moberg, & Nissen, 2010; Velandia, Uvnäs-Moberg, & Nissen, 2012). Skin-to-Skin Contact (SSC) also improves mother and baby bonding and attachment and, makes breastfeeding easier (Velandia et al., 2010), and also increases the mother's attachment to her baby (Vakilian, Doost, & Khatami, 2007).

Maternal attachment behavior differs in different cultures (Cassano & Maehara, 1998; Vakilian & Khatami Doost, 2007). In a study, Cassano and Maehara concluded that Japanese mothers used to do behaviors like smelling, talking, touching and face to face contact with their babies while the Brazilian mothers used to look closely, touch finger and cuddle their babies (Cassano & Maehara, 1998). In a similar study conducted by Vakilian et al. in Iran, it was concluded that the mothers mostly caressed their babies and talked to them (Blumberg & Lucas, 1996).

Studies indicate that despite the importance of attachment between parents and babies, neonatal nurses often give priority to meeting the medical needs rather than involving themselves in making relationships between parents and their babies. It is while the neonatal nurses, as the primary care providers, must have an understanding of how to promote parental attachment based on the familycentered care philosophy. Positive touch or skin-to-skin contact and therapeutic communication can potentially increase this attachment (Hopwood, 2010).

According to the Scientific Information Database of Iran (SID, IRANDOC), only a few studies have been conducted on the skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section in Iran (Beiranvand, Valizadeh, & Hosseinabadi, 2014; Toosi, Akbarzadeh, Zare, & Sharif, 2011). Besides, the few conducted studies have mostly focused on premature babies, and the advantage of this method for term newborns has been less considered (Arzani et al., 2012; Heidarzadeh, Hosseini, Ershadmanesh, Tabari, & Khazaee, 2013). This study has been conducted at a hospital in South East of Iran aiming at investigating the effect of early skin to skin contact on maternal attachment behaviors in newborn after caesarian section.

It is a randomized controlled trial study, which was performed on 80 pairs of mothers and newborns who were randomly assigned into two groups of skin contact and control. The study population included all mothers who had undergone cesarean section with spinal anesthesia. Inclusion criteria include: Iranian nationality, having at least the reading and writing literacy, natural pregnancy, singleton and term pregnancy, and exclusion criteria were: maternal diseases, such as diabetes, gestational hypertension, heart disease and mental disorders, premature rupture of membrane (above 17 hours before surgery which requires newborn admission in the neonatal ward), the mother failed marriages, unwanted or illegitimate pregnancies, maternal addiction, rejection of the baby gender by mothers, history of infertility, and loss of child, respiratory distress and cyanosis of the baby, meconium of amniotic fluid, neonatal anomalies (diaphragmatic hernia and central nervous system anomalies), and any reason that requires neonatal resuscitation or admission in the neonatal intensive care unit.

The research setting was considered to be the operating room of a hospital in South East of Iran as the only maternity hospital affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Science in 2015. After obtaining the permission of the Ethics Committee of the Kerman University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.KMU.REC.1394.392), the data were collected continuously and randomly for six months from eligible samples on separate days (to avoid a sense of discrimination among patients). After examining the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the mothers, the informed and written consent was taken from the mothers, and then they entered the study.

The sample size was calculated to be 80 people using the article "Comparison of Yaxon touch and gentle touch for behavioral responses in preterm newborns (Bijari, Iranmanesh, Eshghi, & Baneshi, 2012) with a standard deviation of S=0.76 and formula

δ=/0/76

d= μ1- μ2

d=0/5

α= 0/05, (1- β=0/8)

The instrument used to measure the maternal-infant attachment was Maternal Attachment Behaviors Scale developed by Kay Avant based on concept analysis, and its validity was first determined by him. This questionnaire was translated to Persian by Vakilian, and then some changes were applied to the questionnaire. Also, it was confirmed in the Persian research by Vakilian et al. and Tousi et al. (Toosi et al., 2011; Vakilian & Khatami Doost, 2007). The reliability of this scale was also confirmed via inter-rater reliability which was measured to be 0.90 in Karbandi's study, and it was measured to be 0.98 in Vakilian study (Karbandi, Momenizadeh, Hydarzadeh, Mazlom, & Hasanzade, 2015; Vakilian et al., 2007).

During an infant feeding, the observer noted the presence or absence of 13 specific maternal behaviors. In the first 30 seconds of each minute, the behaviors were observed. And during the second half, these behaviors were recorded; each observed behavior was recorded once per minute. On the whole, the observation took 15 min, therefore; each behavior was observed for a maximum of 15 times in 15 minutes. In general, 13 behaviors could be observed in 15 min, and one score was allocated to each observed behavior in one minute (total score=195). The sum of scores presented mother-infant attachment, and high scores indicated strong attachment. The three subscales are: Emotional behaviors (looking at, touching, kissing, talking, smiling, checking, and patting the infant); proximity behaviors (holding the infant, embracing the infant with both arms, and close body contact with infant); caretaking behaviors (nursing or bottle feeding, burping, and undressing or uncovering the infant.

In the intervention group, immediately after birth, the baby was transferred to radiant heat, and after drying and clearing the airway, the primary examinations were performed on the baby's health, and the baby was placed on mother's chest transversely in the prone position and was covered with a warm wrapper. A caregiver supports the baby to prevent his/her falling. In the control group, the baby was transferred immediately after birth to radiant heat and routine care (drying, cleaning, and dressing) was carried out and then, the baby was transferred to the baby's room or delivered to their father or mother's companion.

Skin-to-skin contact was being performed at the maximum time, and when the mother was transferred to the recovery room, the newborn was placed in the mother's arms in a semi-sitting position, and the newborn was being fed or taken care of by mother. At this time, by using Avant behavior checklist, the mother's behaviors during breastfeeding were considered as the best time to record the mother's behaviors with her baby during breastfeeding (Vakilian et al., 2007). The researcher was responsible for collection and record of information in all stages, and the mothers were aware of the study and participated in it voluntarily, but they were not aware of the variable being evaluated.

The criterion for the difference between the two groups was the mean difference among the number of behaviors in three behavioral groups and the total number of attachment behaviors. In the control group, after performing routine cares, and transferring to the recovery room, the baby was put in the mother's arms, and then the behaviors were recorded in the same way.

Demographic and midwifery information was also obtained from the medical record and the patient.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage of demographic variables and other variables. Chi-square and Fisher tests were used to compare the distribution of variables between intervention and control groups. Friedman and regression tests were used to investigate the effect of the skin-to-skin contact on maternal attachment behaviors, and the significance level in this study was considered to be (0.05).

Regarding the demographic variables, no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups. The results of data analysis showed that the mean age of mothers in the intervention group was (28.1 ± 6.5) and in the control group, it was (30.4 ± 6.5) (P=0.11). Most of the mothers had high school or higher educations (P=0.8). Most of the subjects had an average economic situation (P=0.86). Most of the mothers lived in the city (P=0.99), and they were housewives (P=0.78). The majority of mothers lived with their husbands, and there was no case of divorced or widowed mothers, but 10% of mothers in both groups lived away from their husbands (P=0.99). In each group, almost half of the samples had a cesarean section in the emergency conditions and half of the samples had an elective cesarean section (P=0.99). The highest cause of cesarean section was associated with the previous cesarean section, and other causes were distributed evenly between the two groups (P=0.62).

In each group, almost half of the babies were girls and half were boys (P=0.99). Regarding the birth order, half of the infants in each group were chosen among the firstborns to avoid the disturbing effect of mothers' first child and the other half were the second borns or next children (regarding the random samples), but on average, in the intervention group was (1.8 ± 0.95) and in the control group was (1.9 ± 1.06) and (P=0.74). The mean age of neonate in the intervention group was (38.5± 1.2) weeks and in the control group, it was (38.3± 0.9) weeks and (P=0.35). Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes in both groups for all babies was 9 and 10, respectively. The average weight of the newborns in the intervention group was (3089.8 ± 475.3), and in the control group, it was (3086.8 ± 395.1) and (P=0.28). The number of pregnancies (P=0.35) and the number of abortions (P=0.21) were also similar in both groups, and no significant difference was found in these variables between the two groups.

The mean and standard deviation of the time of skin to skin contact between mother and baby during cesarean section was (33.25 ± 5.45) minutes.

Generally, according to the Friedman test, among all attachment behaviors, emotional behaviors were the highest observed behaviors, and the caring behaviors were the lowest ones. The mean and the standard deviation of the emotional behaviors in the intervention group was (24.8±9.9), and in the control group it was (15.4±7.05), so there was a significant difference between the two groups (P=0.0001). The mean and the standard deviation of the proximity behaviors in the intervention group was (14.8±0.9), and in the control group, it was (13.8±2.3), so there was no significant difference between the two groups.

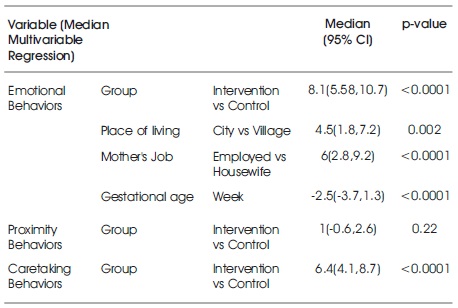

The most observed behavior in the subgroup of emotional behaviors belonged to looking at the baby and in the subgroup of proximity behaviors belonged to embracing the infant with both arms and in the caring behaviors belonged to the breastfeeding. However, the lowest observed behavior among the emotional behaviors belonged to kissing in the intervention group, and it belonged to patting in the control group. Besides, in the subgroup of proximity behaviors, it was related to holding the baby without close contact with mother's body, while it was also related to burping. Generally, these two behaviors were not done by any mother. The average of emotional, proximity and caring behaviors in the intervention and control groups indicated that the total means of emotional and proximity behaviors declined and that of the caring behaviors increased over the time (Tables 1 and 2).

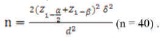

Table 1. Effect of Early Skin-to-Skin Contact and Demographic Variable on Attachment Behavioral of Mothers in Control and Intervention Group

Table 2. Distribution of Attachment Behaviors in Intervention and Control Group

Regarding the impact of demographic variables on attachment behaviors, the results of regression test showed that within an average 15-minute assessment, the emotional behaviors of mothers who lived in the city was higher than 4.5 scores compared to mothers who lived in the rural areas (P=0.002), the mean emotional behaviors of employed mothers was also 6 scores higher than that of housewives (P<0.0001). With each one-week increase in gestational age, the number of emotional behaviors declined by 2.5 scores (P<0.0001). Other variables did not affect emotional behaviors. Demographic variables also have a significant effect on proximity and caring behaviors.

Cesarean section, fetal hospitalization, mother's sickness and some popular conventional methods that can lead to the separation of mother and baby during the first hours after birth interfered with the process of attachment. Frank, Cox, Allen, and Winter (2005) argued that mother-infant separation causes disruption or delay in the mother-infant attachment.

The sooner and stronger the emotional bond with the child, the more desirable and enjoyable the caring of the baby. Also, breast-feeding, motherhood, can be combined more successfully and it reduces the likelihood of child abuse. One of the supporting actions to make an attachment with a baby is the skin-to-skin contact, which creates a healthy child-parent relationship (Flacking et al., 2012). These actions accelerate the development process of the child and flourish his/her potentials. Since the child's mental and psychological health is closely related to maternal health, maternal mental health promotion can be effective in protecting public health (Toosi et al., 2011). Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effect of skinto- skin contact immediately after birth by cesarean section on maternal attachment behaviors on 80 mother-newborn pairs in two skin contact and routine care groups. The results showed that there is no significant difference between the two groups in demographic variables. Among all attachment behaviors, emotional behaviors were the highest observed behaviors, and caring behaviors were the lowest observed behaviors. The results of this study are consistent with the study of Vakilian et al. (2007).

The results of attachment behaviors regarding each behavioral group showed that in the emotional behavior group, looking at the baby has the highest average in both groups, but there is a significant difference between the two groups (p=0.003). The lowest observed behavior in the intervention group was related to kissing the baby and in the control group, it was related to the rocking of the baby. The results of Vakilian et al. (2007) study showed that most mothers' attachment behavior was kangaroo mother care before discharge and it was significantly different with mother's first contact with the newborn in the control group. So, in the emotional behaviors, looking at the baby was done most in both groups and then the most practiced behavior was talking. Thus, these results are consistent with the results of the present study. In Vakilian et al.’s study, the lowest observed behavior was related to touching the baby, but the lowest observed behavior in this study was related to kissing the baby which shows that these results are not in line with the results of the present study (Vakilian & Khatami Doost, 2007).

Feldman et al. in 2002 reported that in mothers with kangaroo mother care, more emotional behaviors such as cough of the baby were seen (Feldman, Eidelman, Sirota, & Weller, 2002). Skin-to-skin contact is a human touching intervention, which creates an enthusiastic dependence in mothers, reduces anxiety, and completes the process of motherhood (Moore, Anderson, & Bergman, 2007).

Regarding proximity behavior, which is one of the components of attachment behaviors in this study, no significant difference in all proximity behaviors was found between the two groups which indicated that skin-to-skin contact does not have a significant effect on proximity behaviors. However, the mean mother's proximity behaviors in the intervention group during 15 minutes were one point more than these behaviors in the control group.

Among the proximity behaviors in the intervention group, embracing the baby with both arms was the most observed behavior, while in the control group the most practiced behavior was hugging through close contact with the mother's body and hugging without close contact with the mother's body was not found in any group. Thus, differences in behaviors between the two groups are statistically significant.

In Vakilian et al. (2007) study, the proximity behaviors such as hugging with close contact of the infant and mother and hugging the baby by holding the arms around the baby respectively occurred most, so these results are similar to the control group results while they are not consistent with the results of the intervention group. But, there is a significant difference between the intervention and control groups (Vakilian et al., 2007).

The results of Feldman et al.’s study (2002) on 146 mothers with premature newborns showed that mothers with kangaroo mother care showed proximity behaviors such as hugging (Feldman et al., 2002).

Caring behaviors were other results of this study that showed a significant difference between the two groups and the most observed behavior in this group was related to breastfeeding due to positive impact of skin contact, which can result in the success of baby's nutrition through breastfeeding. Thus, mothers who were in skin contact group achieved more success in the beginning and continuation of breastfeeding to their baby (p>0.0001). The lowest observed behavior in this group was related to tapping the back of the baby to empty his stomach air (burping), so in general, none of the mothers did this behavior, which seems to be due to mothers' positions and pain and also mothers' conditions after operation. Also this behavior was less observed in dressing and sorting the baby's cloths. There was no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.22).

In this context, in Vakilian et al.’s study, the most observed caring behavior in both groups was related to sorting the baby's cloths, which showed no significant difference with the control group and the two studies are different in this regard (Vakilian et al., 2007). It seems that the difference in the type of delivery is effective on the result of caring behaviors.

The results of the study by Worku and Kassie (2005) on 123 mothers with low weight newborns showed that 62 mothers with kangaroo mother caring felt happy in taking care of their babies (Worku & Kassie, 2005). Also, regarding the attachment behaviors and demographic variables in each behavioral group, the results showed that rural mothers and housewives showed fewer emotional behaviors than employed mothers and those who lived in the city. In this field, no relationship was found with Vakilian et al. (2007) study because in their study all the participated mothers were housewives (Vakilian et al., 2007). Results also showed that the increase in gestational age decreases emotional behaviors. In proximity and caring behaviors, no significant relationship was found between these behaviors and the demographic variables.

Cassano and Maehara believed that cultural characteristics can affect attachment behavior. In their study about attachment behaviors in Japanese and Brazilian cultures, they found that although the perception of women was similar, there are differences in the behavior of these two cultures. For example, most Japanese mothers looked at their babies, but they did not touch them. They also showed more behaviors, such as smelling, talking, and putting their faces on the babies' faces. Brazilian mothers devoted less time to see the baby, but they spent more time to take care of the baby actively, they showed behaviors, such as looking carefully, touching with a fingertip, and holding the baby (Cassano & Maehara, 1998).

Due to the high rate of cesarean section in Iran (Davari et al., 2012), it is recommended to do non-medicinal treatments in taking care of the patients after cesarean section to reduce the physical and psychological symptoms resulting from surgical approaches. Based on the findings of the present study, skin contact between mother and newborn plays a significant role in increasing the attachment behaviors of mothers with cesarean section. Thus, it is suggested to teach mothers this simple, inexpensive and enjoyable technique as a component of prenatal care to achieve the results and take a short step to the mental health of mothers and baby. Due to cesarean situations and the separation of mother and baby during the first hours of birth, the use of this caring method should be emphasized in the operating room. It is recommended that some studies are to be conducted to investigate the attachment behaviors in different ethnicities, to run the promoting and training programs regarding the local culture of each area. Even though this study was conducted in a baby-friendly hospital, skin contact was not used as routine care after birth by cesarean section. Therefore, it is suggested that in future studies, the challenges and difficulties in doing skin contact in the operating room be reviewed and effective solutions be determined to resolve it.

The sense of shame of mothers to show their maternal attachment behaviors despite the patient privacy, pain after cesarean, mothers' position after surgery in the recovery room, and lack of mothers' mobility were the obstacles, which affect the mothers' breastfeeding and attachment behaviors, especially the caring behaviors.

I would thank the kind professors in Nursing and Midwifery Department in Kerman Razi University. Besides, I appreciate the staff and authorities of a hospital in South East of Iran especially nurses and supervisors of the operating room, and also my last thanks goes to mothers who participated in this study.