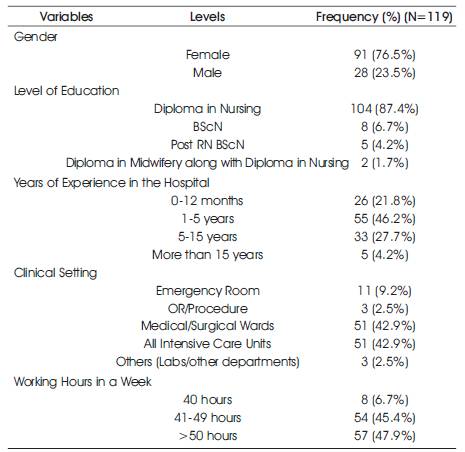

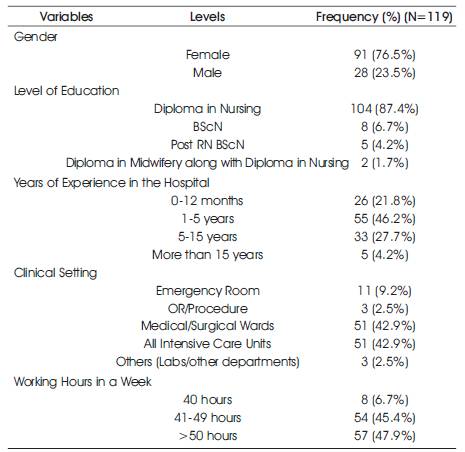

Table 1. The Demographic Characteristic of Study Participants

Medication management requires multidisciplinary collaboration among nurses, physicians, pharmacists, and others. Nurses play an important role in the final step of the process and can elicit a critical role in its prevention. In an effort to prevent medication errors committed by nurses at a hospital, the authors conducted a study to identify frequency, types, and perceived factors of medication errors. A descriptive cross-sectional study design was employed in a private tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. A sample of 119 nurses were recruited from different units of the hospital. Perceived facilitating factors for medication safety and contributing factors for medication errors were identified using researcherdeveloped self-reported questionnaire. The prevalence of medication errors was found to be 21%. More than half of the reported errors by nurses (52%) occurred within six months of their clinical practice and during their night shifts (56%). The most prevalent type of error was administering wrong dose to a patient (48%). Factors that were perceived to contribute to medication errors were: documentation by nurses prior to medication administration (54.6%), shortage of nursing staff (32.8%), and environmental interruptions during medication preparation (26.3%). Factors which were perceived to enhance medication safety included: appropriately labeled medications by pharmacists (55.5%), delivery of precalculated doses from pharmacy (63.9%), and preparation of medications solely by the assigned nurse (51.3%) Providing electronic medication administration system is a key in limiting and preventing medication errors committed at any phase of the medication management process.

Medication Management (MM) is a multidisciplinary task which requires a collaborative approach among health care professionals (Leufer & Cleary-Holdforth, 2013). Collective contribution from physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other allied health workers make the process of MM safe and efficient. The process of medication management initiates from prescription of the medication by physicians followed by its preparation and dispensing by pharmacists and administration by nurses to patients. The chances of error pervade all the stages of the process (Elden & Ismail, 2016). Among different types of medication errors, the most prevalent one is noted in the administration phase; the second commonly reported phase of medication error is the prescription phase (Tang et al., 2007). Traditionally, safe medication administration is believed to be one of the critical nursing practices. Nurses, because of carrying out the most critical step of medication administration, are considered to be eventually accountable for safely administering medications to their patients (Gülsah et al., 2012; Leufer & Cleary-Holdforth, 2013).

Armitage & Knapman (2003) noted that approximately 40% of the nurses' time, is consumed in the medication administration process. By virtue of their role in the MM process, nurses get the most crucial opportunity to ensure safety of the entire process (Leufer & Cleary-Holdforth, 2013) , and therefore, can play a critical role in preventing medication errors. In an attempt to follow the best practices in MM, 'five rights' are essentially performed by nurses; including, right time, right patient, right route, right drug, and right dose (Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014). Lately, Right documentation is also widely considered as an important right to follow.

Despite availability of various frameworks to ensure medication safety, several factors have been identified to be associated with medication errors at individual and organizational levels. Some of the individual factors that have been reported to increase the likelihood of medication errors, include: nurses' lack of knowledge about the medications, poor calculation skills, less years of experience, unable to follow safe and appropriate organization routines, nurses and other health care professionals' negligence and forgetfulness, improper documentation, and drug abuse Chang and Mark Armitage and Knapman, 2003 cited by O'Shea; Tucker, et al. as Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014, Ehsani et al., 2013. Moreover,increased workload, environmental distraction and interruptions, dearth of sufficient institution guidelines and policies; especially with regard to using look-alike medications are key predictors of medication errors Chang and Mark; Armitage and Knapman ;O'Shea; Tucker, et al. as cited by (Bergqvist, Karlsson, Björkstén, & Ulfvarson, 2012; Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014; Ehsani et al., 2013).

At many times, it is difficult to obtain accurate statistics of incidences of medication errors, especially in developing countries like Pakistan due to constraints of the health care system with regard to unavailable or inadequate archiving and data registration and reporting systems. As a result, the data remains under reported and un-analyzed for possible causes (Cheragi, Manoocheri, Mohammadnejad, & Ehsani, 2013). Additionally, despite of acknowledging the moral obligation and benefits of reporting medication errors, a fear of punishment prevails among the health care providers including nurses, which refrains them from admitting and reporting the errors (Cheragi et al., 2013). In lieu of this, it is speculated that medication errors occur at the much higher rate than what is being reported (Güneş, Gürlek, & Sönmez, 2014).

Recognizing that nurses' role comes at the last step in the MM process, the authors held it important to explore nurses' perception about medication errors at the hospital. Also, in an effort to prevent medication errors committed by nurses at the hospital, they believed that determining the prevalence and type of medication error and its causes is the first and critical step. Therefore, this study was undertaken.

The purpose of the study was to determine the prevalence of different kinds of mediation errors and explore perceived factors contributing to medication errors.

The objectives of the study were:

In this study, a descriptive cross-sectional study design was employed. The data was collected from a tertiary care private hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, between August and September, 2014. It is a 300-bedded hospital providing state of the art services for various acute and chronic diseases. There are several departments for adult and pediatric medical care; separate intensive care units for medical, surgical, neonatal, and emergency conditions; separate dialysis unit; and distinct quality care units/theatres for diagnostic and interventional procedures. The hospital is surrounded by crowded residential area and it offers its services to diverse population segment. Patients from different socioeconomic sectors avail the services. Within the hospital, there are general, semi-private, private, and VIP suites available.

The inclusion criteria were, a registered nurse with a minimum qualification of diploma in nursing, certified for medication administration, and willing to participate in the study. A non-probability consecutive sampling technique was used to collect the sample for the study. All the nurses working in the hospital, from August 2014 till September 2014 were approached and explained about the purpose and procedure of the study. Those who agreed and gave a written informed consent were included in the study. A total of 119 nurses participated in the study. The study was reviewed, approved, and permitted by the departmental head of the hospital.

The data was collected using a self-developed questionnaire prepared by the research team after an extensive review of literature, and experience of the nurses who had worked in the clinical setting for more than a decade (Bahadori et al., 2013; Güneş et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2007). The questionnaire contained three sections. The first section obtained sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The second section identified the prevalence, type, and reporting of medication errors. The third section explored perceived factors related to medication error, on a four point likert scale (0= always to 3= never). Three drafts of the third section were prepared and reviewed by the research team. Ambiguous and redundant items were either deleted or replaced with the more cohere stems. The final version of the tool was edited by a language expert. Content validity of the questionnaire was obtained from five experts, including: a registered nurse, a nursing supervisor, a medical superintendent, a pharmacy manager, and a physician. The experts rated the questionnaire on a 4 point likert scale for relevance and clarity. They also provided suggestions regarding the items which were rated less clear or relevant. After incorporating the suggestion of the experts, a repeat measure of Content Validity Index (CVI) for relevance was obtained which was found to be 0.74 for relevance and 0.70 for clarity. The questionnaire was pilot tested on 5 participants before initiating the data collection, whose data was excluded from the final analysis.

The questionnaire as well as written informed consent was distributed to all the nurses working in the hospital in each shift by one of the research team member. Morning and evening shifts each were of six hours (0800-1400 hours and 1400-2000 hours, respectively). The night shift was of twelve hours (from 2000 to 0800 hours). Nurses who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study returned signed consent and filled questionnaire to the member of the research team (data collector) within a week. The data collector reviewed questionnaire for completeness. Any missing information was filled then and thereafter inquiring from the participant.

The nurses were explained about the research. They were assured that their identities will be kept confidential at all levels of the study and the data will be kept secured. Separate identification numbers were given to maintain anonymity of the participants. Data was kept under lock and key and was accessed by the two members of the research team. Written informed consent was obtained.

The data was entered and checked for accuracy and completeness using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Coding of the negative items was reversed. Descriptive statistics was calculated to analyze all the sections of the questionnaire to perform meaningful analysis of perceived factors. Five point likert scale was reduced to a three point likert scale on the basis of the factors affecting medication errors with a specified frequency.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Out of 119 participants, majority were female (76.5%) having a three year diploma in nursing (87.4%). All the nurses were working in three shifts. More than half of the nurses had a clinical experience of 0- 5 years (70%). More than two third of the sample came from medical surgical and intensive care units (85%); whereas, rest of the sample represented emergency, operation theatre and laboratories. Majority (93%) of the participants worked for >40 hours/week.

Table 1. The Demographic Characteristic of Study Participants

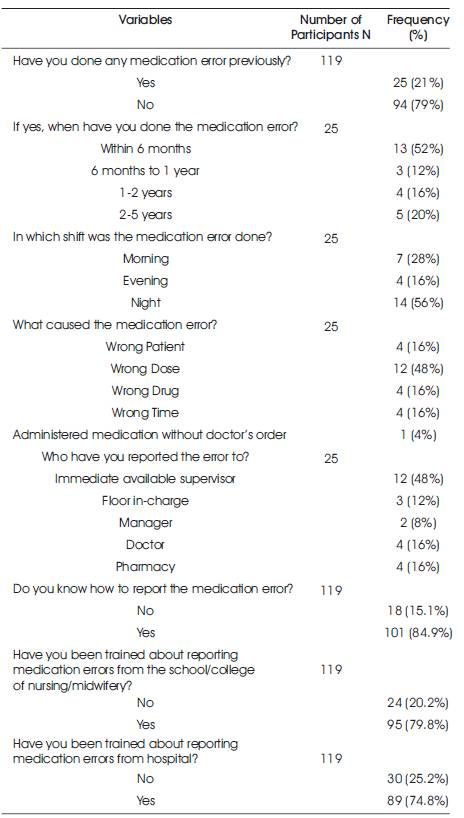

As illustrated in Table 2, majority (79%) of the participants did not acknowledge committing any medication errors; only 25 (21%) of the entire participants shared that they had committed errors at least once in their clinical practice. Among those which were reported, the highest number (52%) of medication errors occurred within six months, during night shifts (56%), due to the administration of wrong doses to the patient (48%). With regard to reporting the medication errors, most errors were reported to the immediate available supervisors (48%) and almost all the nurses (84.9%) were aware about the error reporting channel. The most common source of awareness of medication error appeared to be either their nursing school/college (79.8%) or on the job training (74.8%).

Table 2. Type and Reporting of Medication Errors

Moreover, the factors affecting medication errors were grouped together into six broad categories which included: completeness of the medication orders, clarity of medication orders, quality check at pharmacy level, quality check at nurses' level, nurses' competency, and other environmental factors. Among others, some of the key factors perceived as contributing to the medication errors were: shortage of nursing staff (32.8%), environmental interruptions during medication preparation (26.1%), and documentation by nurses prior to medication administration (54.6%). Likewise, factors which were perceived as facilitators of medication safety included: appropriately labeled medications (55.5%) as well as delivery of pre-calculated doses (63.9%) from the pharmacy, and preparation of medications solely by the assigned nurse (51.3%) (See Table 3).

This study provided an insightful information regarding the medication management in a resource constraint health care system. The study intended to meet the following three objectives: to determine frequency of medication errors by nurses throughout their clinical practice, to identify the types of the medication errors occurred, and to explore perceived factors affecting the medication errors.

They found only a few nurses who have committed medication errors at some time in their clinical practice. Other studies (Cheragi et al., 2013; Güneş et al., 2014) have reported higher rates of medication errors committed by nurses than what we found. Likewise the current study, these studies also used self-reported questionnaire to identify prevalence of medication errors. This substantial difference among the findings of the study from these studies could be perhaps, nurses in this study were afraid of administrative penalty in case of acknowledging the error. Other researchers are of the opinion that under reporting of medication errors by nurses is because of presumed penalty from their administrators or colleagues, and fear of being blamed and losing their jobs (Ulanimo, O'Leary- Kelley, & Connolly, 2007) .

Most of the errors were committed in the medical-surgical and intensive care units. A study by Agalu, Ayele, Bedada, & Woldie (2011) reported that more than half of the errors (52.5%) occurred in the intensive care units, despite of having a more controlled environment. This is quite explanatory acknowledging the increased work pressures in these units. It could also be due to insufficiently trained nursing workforce (Agalu et al., 2011). In connection to this, it is noteworthy that in this study, most of the errors were acknowledged by those nurses who had less than sixmonths of clinical experience and who had acquired only a basic level of nursing education; a 3-year diploma in nursing. Moreover, in the hospital, freshly graduated nurses are made independent in their work without any comprehensive orientation to the unit and its policies. Hence the length of time required to transit a novice nurse to an expert is shortened and often unguided which consequently results in errors. It is well noted in the literature as well that graduate nurses need effective mentoring to address the challenges of role transition (Hofler & Thomas, 2016).

With regard to reported medication errors, the most common error identified in this study was administration of wrong dose to a patient. This affirms the findings of other studies which also report that administration of wrong medication dosage is one of the most prevalent medication error (Bergqvist et al., 2012; Cheragi et al., 2013; Güneş et al., 2014). Moreover, the study showed that most of the errors were committed during night shift. This is not an unexpected finding considering the fact that changes in the circadian rhythms lead to fatigue and sleep deprivation. Consequently, vigilance and performance are affected (Anderson & Townsend, 2010). Probability of committing errors at night is also heightened with longer working shifts, increased work load, and inadequate nursing staff. These factors were also key contributors to medication error in the study where due to staffing shortage, nurse to patient ratio was high; 1:10-12 in general ward setting, and 1:2 in critical care units. Also, the nurses reported to work for more than 40 hours in a week because of an insufficient nursing workforce. Staffing shortage is a ubiquitous problem in the nursing profession which has also been reported by numerous earlier reports (Bergqvist et al., 2012; Cheragi et al., 2013; Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014).

The participants of the study also considered various nursing and physician related factors accountable for medication errors. For example, physician's illegible writing and use of abbreviations on the prescriptions increased the possibility of medication errors. Unclear and ambiguous handwriting with non-standardized abbreviations is open to interpretation by pharmacists and nurses and increases the chances of error. The findings from this study corroborate with findings from earlier studies (Cheragi et al., 2013; Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014; Güneş et al., 2014). Additionally, in this study, it is noted that physicians gave verbal orders even in non-emergency situations, which is perceived by nurses to be one of the factors for medication errors. Since in this hospital, like many public and private hospitals in Pakistan, electronic medication administration system is not available; therefore, physicians either manually write prescriptions or prefer to give a verbal order. Nurses are also inure to verbal orders; therefore, most of the times, the order is not validated. Perhaps, this potentiates the risk of errors in this context. This may be a strikingly different finding in terms of medication management system prevailing in Pakistan which increases the likelihood of medication errors as compared to western countries.

In line with previous researches (Bergqvist et al., 2012; Drach-Zahavy et al., 2014; Güneş et al., 2014; Westbrook et al., 2010), these findings also revealed that nurses considered that they commit medication errors when there are interruptions within the unit at the time of preparing medications. Additionally, another contributing factor that emerged from these findings is that nurses believe that they are likely to commit errors when they sign the medication charts prior to actually administering medications to their patients. It may result in nurses' forgetting to administer medications, patients refusing to take them later, or repeating the dose by another nurse. This is another important factor to errors well documented in the literature (Elliott & Liu, 2010).

Identifying factors that enhance medication safety can significantly contribute to preventing medication errors. Perhaps the most novel finding in this regard is that, in this study, the nurses are of the opinion that pharmacy can play a substantial role. If pharmacists dispense appropriately labeled medications; especially for high alert medications, with pre-calculated doses, dilution errors can be prevented. It means that most of the nurses' efforts and time will be saved. It will also avoid risks associated with nurses' poor mathematical skills in drug dosage calculations. It is also recommended in earlier reports that pharmacist can play an important role by dispensing 'ready-to-administer' dosage which decreases manipulation of drugs by nurses (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 1993).

In this study, nurses also perceived that medication safety can be enhanced if a nurse prepares and administers medication solely by herself. Although, findings of this study do not suggest occurrence of such medication error, it was perceived as a strong contributor to medication error. In a study by (Tang et al., 2007), it was reported that due to increased work and time pressures, assigned nurses of morning shifts prepared medications for evening shift nurses, which has increased risks of errors.

The strengths of the study include its sample size which comprehensively unveiled the process of medication management and highlight the eminent factors. Also, inclusion of the participants from various units of the hospital clarified the phenomenon in detail. However, given the cross sectional design of the study, nonprobability sampling technique and want of inferential statistics, generalization of the results shall be done cautiously. Likewise, all the data is self-reported which may have resulted in under reporting of the errors. Hence, it is suggested that a large scale study shall be performed along with the validation of errors from the records using a universal sampling approach for an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon.

Medication errors can be prevented at all steps of medication management process with the facilitation from hospital's management. In this regard, introducing Electronic Medication Administration Record Systems (EMARs) with the use of barcode system is an essential step. Specifically, errors by nurses can be easily prevented if hospitals provide enabling environment to reduce interruptions at the time of medication preparation, provide comprehensive orientation to novice nurses at the time of beginning their clinical practice, and ensure nonpunitive environment. Moreover, medication data archiving system should be strengthened to determine prevalence of the reported errors and to retrieve the types and causes of errors.

Medication errors are preventable and nurses can play a substantial role in enhancing the safety of medication management. The findings of the study suggest that although medication errors are underreported, there is an awareness regarding key factors that contribute to medication errors or enhance the safety of medication management process. However, there is a dire need of an efficient system in the form of EMAR which can reduce the errors contributed by physicians, pharmacists, and above all, nurses who are prime stakeholders of this system.