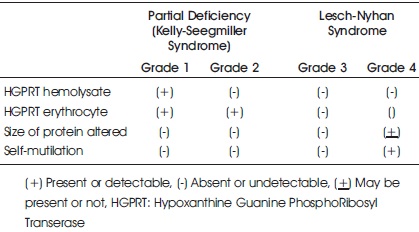

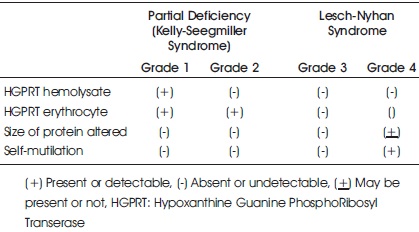

Table 1. Classification of HGPRT Deficiency based on Clinical, Biochemical, Enzymatic and Molecular Data

Lesch–Nyhan is a rare disorder related to X-linked recessive genes that occurs exclusively in males. This happens due to the mutation of Xq26 chromosome and deficiency of Hypoxanthine Guanine PhosphoRibosylTransferase (HGPRT) enzyme. LNS is characterized by classical triad of symptoms like Hyperuricemia, Spectrum of neurological dysfunctions, cognitive and behavioural disturbances including self mutilation. The symptoms occur due to the increased accumulation of uric acid in the body fluids to dangerous levels. The treatment should focus on decreasing serum uric acid level and maintenance of neurologic symptoms. Here we present a case of a 2-year old child admitted in the Department of Pediatrics with self mutilation, increased uric acid levels, delayed milestones and renal failure. After investigations, the diagnosis of LNS was established through various examinations.

Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome (LNS) was first described in 1964 at John Hopkins Hospital. The two brothers Micheal Lesch (a medical student) and William Nyhan (a pediatrician) presented with very unusual symptoms that are severe retardation of motor development, dystonia, choreoathetosis, crystals in the urine and self mutilation. After the publication of the case study, other cases were also reported and recognized around the world, and later it was described (Bell et al., 2016). The Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome (LNS) is an extremely rare X-linked recessive inborn error of purine metabolism. It happens due to mutation in Xq26. Also, there is congenital absence of Hypoxanthine Guanine Phospho Ribosyl Transferase (HGPRT) enzyme. This deficiency causes excessive production of uric acid and consequent hypouricemia (Lesch & Nyhan, 1964; Tewari et al., 2017).

The gene in this incurable disease is only passed on to sons by the mother. However, the females on the other hand are carriers with increased risk of gouty arthritis or otherwise usually unaffected (Seegmiller et al., 1967). HGPRT deficiency leads to the classical triad of features: (i) Hyperuricemia, (ii) Spectrum of neurological dysfunctions (iii) Cognitive and behavioural disturbances (Mohapatra & Sahoo, 2016). The first manifestation that is seldom recognized in early infancy is the presence of urate crystals formation, due to abnormally increased levels of uric acid in urine. This increased uric acid leads to the appearance of orange colored deposits (commonly known as “orange sand”) in the diapers of the babies (Preston, 2007).

The most common occurring features are developmental delay and decreased muscle tone (hypotonia), which appears as early as three to six months of age, and compulsion towards self-mutilation or self-harm which is usually reported at or after 1year of age. These selfmutilating behaviour typically begins as soon as the child's teeth appear and when children try to eat by themselves (Rosenberg & Pascual, 2015), though there is no apparent neurologic dysfunction present at birth (Fauci, 1998; Kostadinov Neychev& Jinnah, 2006).

This behaviour continues with partial or total destruction of perioral tissue, especially the lower lip. Amputation of fingers, toes and tongue which may be partial or total is very much common. The patients diagnosed with this syndrome may stab themselves at the eyes with sharp objects (Kostadinov Neychev & Jinnah, 2006).

The prognosis for LNS is very poor. Many patients die in their teens and those who reach to twenties are often fragile. Most of the LNS sufferers are susceptible to infection and may die from kidney infections. According to the recent studies, respiratory failures play a major part with sudden death in certain cases. Although there are rare cases reported in India, it is approximately 1 in 380,000 live births in Canada and 1:100000 to 1:300000 in world literature (Lesch & Nyhan, 1964).

There are other diseases that involve self-mutilation like destructive behaviour patterns in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome, Tourette Syndrome, Prader-Willi Syndrome, Smith-Magenis Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, Autonomic Neuropathy Type IV, which may be confused with differential diagnosis (Jinnah et al., 2010).

The report presented below is of a two-year old child diagnosed with Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome.

A two year old male child born to 2nd degree consanguineously married couple was presented in the Department of Paediatrics, for dysmorphism, self mutilating behaviour, delayed milestones, self engrossed and irritable behaviour. While recording the history from the parents, it was revealed that the child was born to the parents after normal vaginal delivery (37 weeks) induced due to preeclampsia and fever. The birth weight of the baby was 3.070kg with all the health parameters normal. There was no history of any metabolic or blood disorder. There is no known history of mental retardation, arthritis, asthma, atopy, psychiatric illness or any self-mutilating behaviour in the family.

The child was well during the postnatal period with good muscle activities, good feeding, having bowel and bladder movements normal, and other vitals were stable. On day 2 of its birth, the baby was presented with yellowish discoloration of the eyes and face when a single surface phototherapy was given for one day and the baby was discharged. There was an increase in Serum Bilirubin level 319mg/dl from 232mg/dl. After one week there was a brief episode of shakiness for 2 seconds several times while changing the diaper of the baby with increase in Serum Creatinine which was 102mg/dl (Day 1), 108mg/dl (Day 2), 86mg/dl (Day 3) and again 91mg/dl (Day 4).

Abdominal ultrasound was ordered but it was unremarkable. The child was normal up to 3 months of age, then started having regression of milestones. At 5 months old, his weight was 8kg, height 69.8cm and occipito-frontal circumference 39.5cms. He was not appropriate for his age and showed stereotyped behaviour. He was able to make eye contact, babble, follow objects; hypotonic movements of the limbs were present but the child was not interested in the surroundings and was restless. He had subtle dysmorphic features accompanied with fisting and decreased muscle tone including delayed motor milestones. He could not control his neck properly and not able to sit without support. However, his hearing and vision were normal, though he could not respond to verbal commands effectively. Further the child had abnormality of renal medulla, brisk reflexes, central hyptonia, depressed nasal bridge, developmental regression, hyperuricosuria, macrotia, motor delay, nephrocalcinosis, and a history of prolonged neonatal jaundice.

Results of Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) done at 1year showed that the child has a hemizygous likely pathogenic variant that was identified in the HGPRT1 gene and probable diagnosis of X-linked recessive Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome. At the age of two, the child showed self injurious behaviour with self mutilation and hyperurimia. The level of AST (Aspirate Transaminase) was 50 IU/L (ref. 3-37IU/L), Serum Uric Acid level 519 umol/L (ref. 113-321umol/L), Serum Creatinine level 38 umol/L (ref. 21-36 umol/L), Potassium level 4.90mmol/L (ref.3.3-4.6 mmol/L), Triglycerides level 1.24 mmol/L (ref. 0.1-0.8 mmol/L). Although, the complete blood count, biochemical profile, metabolic screening, karyotype and brain MRI results were normal. On examination, there were wounds presented in the finger tips and perioral region. There were signs of tongue bite, lips bite and nail scratching around the nasal area.

Initially LNS was not considered as the differential diagnosis, as it is a very rare disease. Global developmental delay, cerebral hypotonia with suspected case of genetic syndrome was put forward as a diagnosis. However, the serum uric acid level was found out to be 8.2mg/dl with the striking features of mental, neurological and physical retardation and self mutilating behaviour which helped in reaching for the correct diagnosis. After consultation with the Department of Genetics, a study was carried out on molecular diagnosis of Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome by gene sequencing. The study confirmed the diagnosis of Lesch- Nyhan Syndrome due to mutation in the HPRT gene in the child and also revealed the carrier state of the mother.

Subsequently, the condition was controlled with oral Allopurinol for increasing serum uric acid level. He was advised for occupational therapy and physiotherapy. For self mutilating behaviour, mouth guard was decided and removal of teeths planned in case of severity. He is currently taking treatment for confirmed LNS which is followed by the Departments of Rehabilitation, Genetics, Neurology, Medicine, Nephrology and Odontology.

The diagnosis of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is based on HGPRT enzyme activity measured in the live cells, psychomotor delay, molecular tests, clinical and biochemical findings. The MRI may not be efficient in diagnosis of LNS, as most results are normal (Agarwalla, 2018). Torres and Puig have proposed a classification system into four groups, depending upon clinical, biochemical, enzymatic and molecular analysis (Torres et al., 2012) (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of HGPRT Deficiency based on Clinical, Biochemical, Enzymatic and Molecular Data

Prenatal diagnosis of LNS can be performed with amniotic cells obtained by amniocentesis at about 15-18 weeks of gestation or chorionic villus biopsy obtained at about 10-12 weeks gestation (Torres et al., 2012; Torres & Puig, 2007).

The physicians should be careful while accepting the conclusion because most patients who have hyperuricemia (uric acid level, usually 9-12mg/dl) suffer from LNS, but sometimes it can be presented with only hyperuricosuria (uric acid excretion) and no hyperuricemia. Therefore, a child with delayed development may be checked with uric acid in urine along with the serum. This may be a sign of LNS. The sample may be collected by 24-hour or on the spot on urine to detect hyperuricosuria. However, there may be inaccuracies in the interpretation as the microorganisms present in the urine consume purines, including uric acid in 24-hours urine sample. So, a spot urine sample may be more convenient to collect and analyze for correct uric acid/ creatinine ratio. The reference range in normal children is less than 1 mg as compared to 3-4mg of creatinine in patients with LNS. In literature review, the finding of serum uric acid level was more than 4-5mg/dl and uric acid / creatinine ratio of 3-4 was highly suggestive of LNS14.

Other signs and symptoms include dysarthria, apraxic disco-ordination of lip and tongue, and dysfunction of ocular motor activity. Self mutilating behaviour is integral to the disease but sometimes head banging with injuries to eyes and legs also appears (Lyon et al., 2006).

The confirmatory test for diagnosis of LNS are:

Analysis of HPRT activity in erythrocytes was first mentioned in the report by Seegmiller et al., in 1967 which concluded that the enzyme activities approach to zero in the patient suffering from LNS. Carrier detection may be a limitation in the simple testing of enzyme activity, as in heterozygote it is normal. In the analysis of mutation of the HPRT1 gene, it is located on the long arm of X chromosome (Xq26.1) and encodes human HPRT. It has strengths in being carrier and prenatal diagnosis (Seegmiller et al., 1967).

There is no curative treatment for LNS but symptomatic treatments are possible. The management of the condition may be in steps. For increased uric acid level, the patient is prescribed Allopurinol, which is an oxidase inhibitor proved to be effective in reducing the uric acid concentration. For neurologic symptoms, drugs and rehabilitation such as Benzodiazepine and Carbmazepine can be used. To manage self mutilating behaviour, certain activities like physical restraints like flexible arm splints (to prevent finger biting) can be used. In certain cases the teeth is removed to prevent perioral injuries. However, as per the studies SAdenylmethioine and deep brain stimulation treatments have been reported as proven methods for self–mutilating behaviour.

LNS is a rare disorder. Cases of LNS have rarely been reported in India. It may have a slow progression, but symptoms can be seen relatively soon after birth. From the appearance of orange crystals in infancy to self mutilating behaviour in later years, it is a journey of slow neurological progression. The deficiency of HPRT activity plays an important role in the diagnosis. The child requires constant love and attention. There may be no standard treatment but symptomatically it can be managed. Genetic counselling is highly recommended for parents who have children with LNS.

None

There is no conflict of interest.

Nil

Not required.