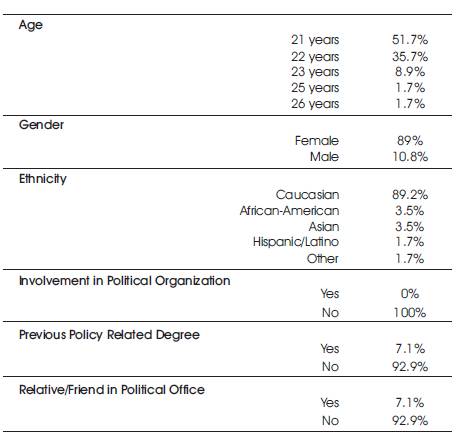

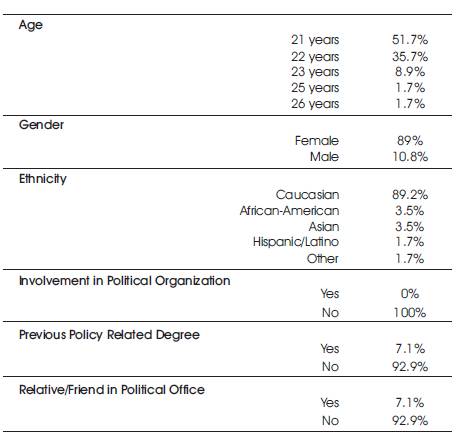

Table 1. Demographic Analysis

Awareness of the importance of political advocacy for both the nursing profession and for patient outcomes is critical to the advancement of health related legislature at the state and federal level. The 2010 IOM report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, recommends that nursing education prepares a workforce of nurses for key government leadership positions. This study evaluated the effectiveness of group participation in a health policy and legislative blog in increasing nursing student self-efficacy scores on political activism. The research design was an evaluative before-and-after design using each participant as his/her own control. The study utilized a convenience sample of 56 senior level nursing students enrolled in a leadership course. A paired-samples t test was conducted to compare the pre-test mean and the post-test mean of a 12 item political self-efficacy survey. The overall self-efficacy score and all three self-efficacy subscales were statistically significant (p<.05) demonstrating a noteworthy increase in self-efficacy for political activism. This study has identified an effective teaching strategy to improve the self-efficacy of nursing students in advocating for the nursing profession and patient outcomes. The outcome of this study was that graduating baccalaureate students enter the workforce with an established level of confidence in their ability to affect change in health policy promotion.

The nursing profession represents the largest portion of the health care workforce in the United States (U.S.) with registered nurses representing 2.6 million in employment in 2008 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). Studies indicate 1 out of every 44 voters is a nurse (DeMoro, 2006). Worldwide, over 13 million registered nurses are currently practicing (ICN, 2010). The profession's large numbers have the power, if actively engaged, to significantly influence health care policies and legislation and to influence policy makers. Nurses are in a unique position to experience firsthand many of the issues of the health care delivery system including access to care, increasing numbers of patients with multiple chronic conditions, quality and safety of services, and the nursing workforce shortage. Therefore, nurses should be visible in health policy decision making and play an active role in advocating for change.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report in 2010 recommending nurses act as “partners in redesigning healthcare (IOM, 2010).” Nurses must have a voice in promoting the health and well-being of their patients, quality delivery of health care services, and the nursing profession itself. The IOM urges nurses to view health policies as something they can actively affect and advance rather than something that happens to them. Staying current on the issues of health care is not only a professional responsibility of nurses but also a social responsibility of global citizens.

A study by Chan and Cheng (1999) found that nurses generally had low political efficacy and a feeling of powerlessness. Also, many nurses feel a lack of knowledge of the political process inhibits their willingness or confidence to participate in legislative issues. Nurses also focus on their clinical role without perceiving how health care policy decisions affect their clinical environments. This lack of knowledge and feelings of powerlessness can lead to political inaction (Des Jardin, 2001). How do we get nurses to move out of their comfort zones and be more actively engaged in the legislative arena?

Hahn (2010) proposed that in order to cultivate future nursing leaders, undergraduate nursing curriculum should incorporate awareness of political issues that impact health care delivery and the nursing profession. Encouraging political activism is a significant role of nursing education to prepare students to practice as leaders and professional nursing advocates in health policy. Nurses become empowered through an education that addresses the political process and actions necessary to be an agent of change (Des Jardin, 2001). A baccalaureate nursing student should graduate prepared to act as a knowledgeable practitioner, a member of a professional organization and an advocate for positive health outcomes and professional advancement (Hahn, 2010).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate if group participation in a health policy and legislative blog was effective in increasing nursing student self-efficacy scores on political activism. For this study, political self-efficacy is defined as one's confidence in the ability to use knowledge and expertise to impact health related policies through personal and professional engagement. Items measured nursing students' self-efficacy on the following: stating political opinions openly; promoting effective information sharing and mobilization in communities (of work, school, friends and family) to sustain political programs in which they believe; playing a decisive role in the choice of the leaders of political movements to which they belong or to which they are near; and influencing others politically.

The convenience sample population consisted of traditional baccalaureate nursing students in the first semester of their senior year enrolled in a nursing leadership course in the U.S. A total of 60 students were invited to participate in January 2011. Participation in the study was voluntary.

The Political Self-Efficacy survey was adapted from Andrews (1998). The pretest and posttest consisted of twelve items on a ten-point Likert scale that were intended to assess students' beliefs in their abilities to engage actively in political activities: 1 (cannot do at all) and 10 (very sure I can do). The survey consisted of four subscales: Opinion, Activism, Decisive Role, and Encourage. The Opinion subscale measures the confidence of the participant to state political opinions openly. The Activism subscale measures the confidence of the participant to promote effective information sharing and mobilization in communities (of work, school, friends and family) to sustain political programs in which they believe. The Decisive Role subscale measures the confidence of the participant to play a decisive role in the choice of the leaders. The Encourage subscale measures the participant's confidence to influence others politically. The posttest included an open ended question: “Please share how you have changed, if at all, by participating in the health policy blog.”

The blog assignment required students to collaborate and actively participate in groups over a five week time period. Groups chose a current health policy related legislative bill at either the state or federal level related to nursing practice, health care consumers, or a health care delivery system that illustrated the necessity for change. The groups then created a blog. On group blogs students described the chosen bill, its sponsors and the actual or potential issue; discussed the governmental objectives, political influences and potential impact of the policy change on nursing, clients and the health care system using scholarly resources; chose a position on the bill; developed and described a political action plan and the steps needed to support the group's position; identified and contacted key stakeholders or legislators and professionally invited them to visit the group blog; and carried out the political action plan determined by the group. Students were asked to visit and comment on other group's blogs on a weekly basis.

A pretest-posttest design was used in this study to evaluate if participation in a health policy and legislative blog was an effective educational strategy to increase nursing student self-efficacy scores on political activism. The study was approved through the Institutional Review Board of James Madison University. Baccalaureate nursing students enrolled in a required leadership course were invited to voluntarily participate in the study during the first day of class. Consent was obtained from all participants. Students who consented to participate were assigned a study number to match pretest and posttest results. These name and number assignments were destroyed after participant completion of the posttests. While students were enrolled in the course, course faculty did not have access to the assigned student numbers or pre-post test data.

The Political Self-Efficacy pretest with demographic survey was administered prior to receiving course content and beginning to work as a group on the blog. Students frequently had the opportunity to directly communicate with those involved in making decisions about passage of the bill and share their expertise and recommendations. The Political Self-Efficacy posttest was administered 1 week after completing the 5 week blog project. Both the pre and post test questionnaires were administered by a fellow faculty member not associated with the course.

All data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and subsequently downloaded into SPSS. Data were analyzed for skewness and missing variables. A total of 60 students completed the pretest and 56 students completed the post test. Only those participants completing both pretest and posttest were retained for data analysis. Demographic data were analyzed for frequency distribution. A paired samples t tests was applied to the four subscales and each individual statement. The open ended question was analyzed for qualitative themes.

A total of 56 participants voluntarily completed both pretest and posttest surveys of a possible 60 participants (93% participation rate). Demographic data is summarized in Table 1. The majority of participants were in their early 20's, female and Caucasian. Data were obtained on participants' involvement in a political organization, having a previous degree in a policy related field, and having a relative or friend in an elected political position to determine if these factors are influential in pretest scores on political self-efficacy. During the initial phase of analysis, it was determined that no participants were involved in a political organization and only 4 (7%) students had a previous degree in a policy related field or a family/friend in political office. No further analysis was completed due to the noncontributory nature of these findings.

Table 1. Demographic Analysis

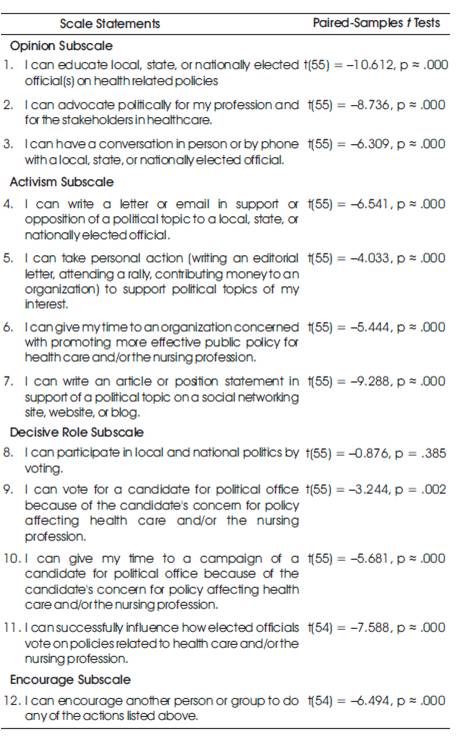

A paired-samples t tests was applied to the four subscales and each individual statement. An alpha level of .05 was used for each analysis. The number of cases used for the analyses was 56. All individual self-efficacy statements were statistically significant (p<.05) except for statement 8 (see Table 2). All four subscales were statistically significant (p<.05). For the Opinion subscale, the test was significant, t(55) = –9.551, p ≈ .000 with the post-test mean significantly higher (M = 7.10) than the pre-test mean (M = 3.96). For the Activism subscale, the test was significant, t(55) = –7.385, p ≈ .000 with the post-test mean significantly higher (M = 8.29) than the pre-test mean (M = 5.91). For the Decisive Role subscale, the test was significant, t(54) = –5.982, p ≈ .000 with the post-test mean significantly higher (M = 8.28) than the pre-test mean (M = 6.74). For the Encourage subscale, the test was significant, t(54) = –6.494, p ≈ .000 with the post-test mean significantly higher (M = 7.93) than the pre-test mean (M = 5.35).

Table 2. Political Self-Efficacy Scale Analysis

The posttest contained one open ended question with 38 responses: “Please share how you have changed, if at all, by participating in the health policy blog.” Four primary themes were identified within participant responses: an increased awareness and knowledge of health care related policies; an increased knowledge and comfort with the political process; an increase in confidence or self efficacy regarding sharing opinions, communicating with legislators, and discussing health policies; and an increased awareness of how nurses can impact policy and how policy can impact nurses.

Awareness and knowledge of health care related policies is a basic foundation to becoming politically active. This theme is expressed by one participant as “After working on the health policy blog, I feel more confident about my knowledge related to health care policy and the resources available to influence change.” The second theme from the participant responses emphasized an increased knowledge and comfort with the political process. This factor is critical to develop in order for nurses to effectively engage in political activism strategies. A participant shares, “I am more confident talking and learning about health related issues in terms of politics. I also understand how policies related to health care are made now. The blog assignment was very important to my learning.” Participants expressed an increased confidence in their ability to actively implement political activism strategies in the third theme. A participant writes, “I am more aware of current issues in health care and feel more comfortable voicing my opinion about them” and another participant shares, “I have a better understanding and feel how politics relate to important concepts and policies in nursing. I feel that I also know who to contact now if there is an issue that concerns me.” The final theme of increased awareness of how nurses can both impact policy and be affected by policy is shared by this participant, “I have gained awareness about caring for policies that affect nurses” and “the need to advocate for nurses.” The emerging themes from the open-ended response question reinforce and validate the quantitative findings of increased political self efficacy for these study participants.

This study has some limitations for discussion. The sample population is homogeneous in gender, age and ethnicity. Participants were predominantly Caucasian females in their early 20's. Therefore findings may only be assumed for a similar population of senior nursing students in the U.S. Replication of this study across other nursing student populations and within other countries will lend strength to outcomes if the findings are similar.

The Political Self-efficacy posttest was administered to individual students within one week of completing the 5 week blog project. Findings demonstrate a statistically significant increase in self-efficacy in the short term period. It is unknown whether this increased political self-efficacy persists as students are distanced from this project. Obtaining longitudinal data on levels of political self efficacy and future engagement in political activism is warranted to determine whether this teaching strategy is effective in promoting a lasting change in confidence for new graduate nurses.

With over 13 million nurses practicing internationally, the nursing profession is the largest healthcare occupation in the world (ICN, 2010). Historically, many of our professional leaders – Florence Nightingale, Lillian Wald, and Margaret Sanger – were effective at advancing our profession and improving health outcomes through their political activism. Currently, women tend to have less political self-efficacy when compared to men which may be attributed to the global trend of males dominating political office (Caprara, Vecchione, Capanna, & Mebane, 2009). Low self-efficacy has been identified as a barrier to political advocacy for nurses (Chan & Cheng, 1999);( Deschaine & Schaffer, 2003). As a female dominated profession, it is critical to focus efforts to increase nurses' political self-efficacy for engagement in political activism and continued professional advancement.

The recent recommendations for nursing education emphasize the role of leadership and health policy for developing a workforce of nurses who are competent and prepared to advocate politically for the profession of nursing and the health outcomes of patients in the current global delivery systems (IOM, 2011). In a study by Rains & Barton-Kriese (2001), nursing students expressed public policy as a barrier to practice and failed to identify their community engagement and service as a foundation for political activism. Thus, in addition to modeling political activism, it is necessary for nurse educators to provide learning strategies that facilitate integration of policy theory with clinical practice to promote political self-efficacy and activism.

This study clearly demonstrates an effective teaching strategy that increases the political self-efficacy of nursing students to feel confident in their ability to contact and educate legislators and stakeholder, get involved in a political organization, and encourage others in political activism. The blog experience provided an opportunity for students to collaborate on analyzing current state or federal legislature and develop a stance on the bill. This assignment required critical thinking, scholarly inquiry, professional communication, persuasive arguments and developing the link between policy and professional practice and health outcomes of patients. Incorporating technology familiar to the millennial student provides a mechanism which translates easily for continued use in professional practice which promotes continued political engagement.

Students were socialized into the role of political advocate with this project and several student groups had the opportunity to communicate directly with U.S. legislators and use their knowledge as a form of persuasive argument for or against a legislative health related bill. Political inaction by nurses has been attributed to a lack of political process knowledge and a sense of powerlessness (Des Jardin, 2001);( Deschaine & Schaffer, 2003). This project provided graduating senior nursing students with the knowledge, skills and empowerment to promote health policy change. This political engagement is consistent with other teaching strategies within nursing programs that promote political activism including participating in a nursing lobbying day (Zauderer, Ballestas, Cardoza, Hood, & Neville, 2009) and serving as legislative interns (Magnussen, Itano, & McGuckin, 2005).

Participants did not show a statistically significant increase in their confidence in voting. In analyzing the group mean for voting confidence, it is evident that a ceiling effect was reached for this specific statement with a pretest M=9.18 and a posttest M=9.38, indicating a high self-efficacy in voting currently for this participant pool. This finding is also consistent with a high voter rating in general among nurses globally (Chan & Cheng, 1999).

Nurses are at the forefront of health care and have the knowledge and expertise to ascertain how to utilize public policy to improve our delivery systems, patient outcomes, and professional practice. With increased confidence in their ability to influence health policy, nurses by sheer number, can effectively advocate for positive change for patients and the nursing profession. This study demonstrates that graduating nursing students can enter the workforce with an established level of confidence in their ability to affect change in the health policy arena.