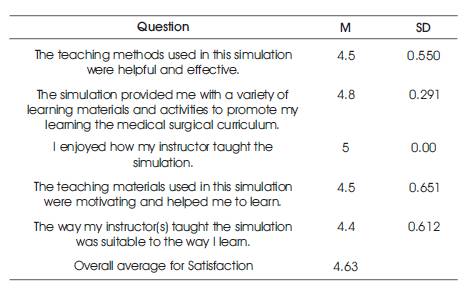

Table 1. Student Satisfaction with Current Learning

The shortage of clinical sites can be a particular problem for rural nursing programs. One remedy to the shortage of clinical sites is to incorporate simulation into nursing curricula. The purpose of this study was to offer high-fidelity simulation opportunities to students in a rural baccalaureate nursing education program. Students' satisfaction with the simulation experiences and self-confidence levels were measured using the Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in Learning tool ( NLN, 2018). Scores indicated a high level of satisfaction with the simulations and a high level of selfconfidence post-simulation. The outcomes support the formal integration of a simulation program into the curriculum of the rural nursing program. Simulation can help overcome barriers to clinical access found in rural nursing programs.

Nursing education across the globe has been transformed by the implementation of simulation. Nursing programs everywhere have built buildings to house expensive equipment and integrate simulation into their curricula. Some nursing programs have limited funding to purchase simulation equipment and may need support from external agencies and organizations. This report highlights one rural nursing program's need to upgrade its simulation capabilities in order to overcome a common barrier in rural nursing education. The NLN Student Satisfaction and Self- Confidence in Learning tool was administered to a group of clinical nursing students (n=90) post-simulation. Results indicated a high level of student satisfaction with the simulation as well as a high level of self-confidence postsimulation.

The nursing program in this study is located in rural Northwest Tennessee. The university hosts approximately 7,000 students per year with 400 pre-nursing students and 110 clinical nursing students. Only two clinical agencies used for student clinical rotations are located within a 30- mile radius of the campus. The remaining clinical sites require significant student travel into urban areas. Additionally, the urban clinical sites host several other nursing programs for clinical rotations. This causes a significant struggle among nursing schools competing for clinical sites. The shortage of clinical sites can be a particular problem for rural nursing programs, as it is for the program in this study. One remedy to the shortage of clinical sites is to incorporate simulation into nursing curricula. Simulated experiences provide the student with opportunities to be involved in patient care may be experiences otherwise not experience in actual clinical settings (e.g., no laboring patients, no post-partum mothers, no pediatric experiences, no patients with complex medical-surgical issues). These patient situations may be low frequency, high impact events, otherwise not experienced.

In addition to clinical placement barriers, the university in this study is a public institution, that functions with a very limited discretionary budget for optional equipment purchases. The investigator determined the need for external funding of simulation equipment was needed and pursued that option. Grant funding was obtained via application to The Promise of Nursing for Tennessee Nursing School Grant Program administered by the Foundation of the National Student Nurses' Association. Funding for the grant program was contributed by several hospitals and healthcare agencies in the Tennessee area, by Johnson & Johnson, and by national companies with an interest in supporting nursing education. The funds were raised at a Gala Fundraising Event sponsored by Johnson & Johnson. The grant funding was used to purchase the simulation equipment utilized in this study.

A simulation research study published by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2014) provided landmark support for nursing programs to replace traditional clinical hours with simulation hours. Hayden et al. (2014) found no statistically significant difference between groups with traditional clinical hours and those with simulation hours in the areas of comprehensive nursing knowledge, preceptor and clinical instructor ratings of clinical competency, and NCLEX pass rates. Students in this study also reported their learning needs were being met.

The purpose of this study was to offer high-fidelity simulation opportunities to students in a rural baccalaureate nursing education program. The original outcome was to increase students' knowledge retention of basic life support skills, physical assessment, cardiac rhythm assessment, and intravenous therapy through the use of the Nursing Anne simulator. In addition to the original objective, it was determined that there was a need to measure students' satisfaction with the simulation experiences and assess how simulation affects their self-confidence. The project was submitted through the IRB at the governing university and was granted full approval; therefore, the Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in Learning tool ( NLN, 2018) was added to measure satisfaction and selfconfidence in students participating in simulations using the newly purchased equipment. This instrument consisted of 13 items using a five-point scale designed to measure student satisfaction with the simulation activity and selfconfidence in learning. Reliability for the Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in learning tool was tested by the developers of the instrument using Cronbach's alpha: satisfaction = 0.94; self-confidence = 0.87 ( NLN, 2018). The instrument is also recommended to be used in simulation programs that are new or being developed, which was the case for the program in this study.

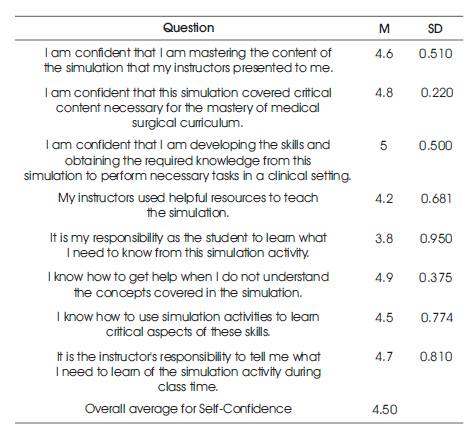

After informed consent was obtained, students in Levels I (n=37), II (n=30), and III (n=23) of the BSN program (total n=90) were administered the Student Satisfaction and Self- Confidence in Learning tool immediately following a simulation in either the fall or spring semester. Five items on the instrument measures the student satisfaction with five different items related to a simulation activity. Eight items measured how confident students feel about the skills they practiced and their knowledge about caring for the type of patient represented in a simulation ( Jeffries and Rizzolo, 2006). The mean score on the tool for satisfaction was 4.63 indicating a high level of satisfaction with the simulation. The mean score for self-confidence was 4.50 indicating a high level of confidence after the simulation and the results are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Student Satisfaction with Current Learning

Table 2. Student Self-Confidence in Learning

The simulations varied for each level of students and involved a mixture of basic life support skills, physical assessment skills, cardiac rhythm assessment, and IV therapy. Knowledge retention was measured by end of course tests and standardized exams.

Qualitative feedback from students indicated that students felt more prepared for the clinical setting following the simulations. Additionally, students were exposed to skills they had not encountered in clinical such as a cardiopulmonary arrest and deteriorating patient scenarios that required student intervention.

The nursing faculty of this program are realizing the multifaceted benefits of simulation. The outcomes of this project will support the formal integration of a simulation program into the curriculum. Faculty members have heard the positive feedback from students thus far, and have seen the effects simulation is having on them and how that translates into the clinical setting. In support, results of the landmark simulation study by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2014) indicate that up to 50 percent of traditional clinical hours could be substituted with simulation without negatively affecting NCLEX-RN pass rates or clinical competency (Hayden et al., 2014).

Simulation is a very important part of nursing education that can affect student self-confidence. Studies have shown that confidence and anxiety levels have a significant impact on clinical performance ( Blum et al., 2010; Khalaila, 2014). Increasing confidence and decreasing anxiety levels prior to the start of clinical rotations has the potential to positively affect retention of students. Exposure to simulated experiences are important for increasing students' self confidence in real patient care situations ( Bambini et al., 2009,). Current research by Lister et al. (2018) supports the implementation of simulations that involve the telehealth and telemedicine to increase student confidence in communicating via this method.

Simulations such as this would be particularly important for rural nursing education programs since they are likely to encounter telehealth/ telemedicine in the rural setting.

In summary, the use of simulation by rural nursing education programs can overcome the lack of clinical sites by offering lifelike patient scenarios. An additional benefit to the use of simulation is that it offers a safe environment for students to learn within. Students can practice clinical judgment and critical thinking without jeopardizing patient safety. The access to simulation equipment can also offer local hospitals/facilities the ability to hold annual skills fairs and other educational events for their nurses in turn facilitating community partnerships.