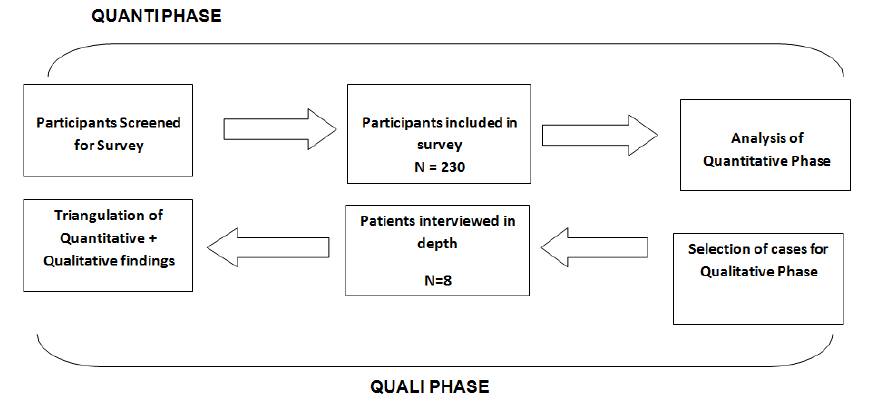

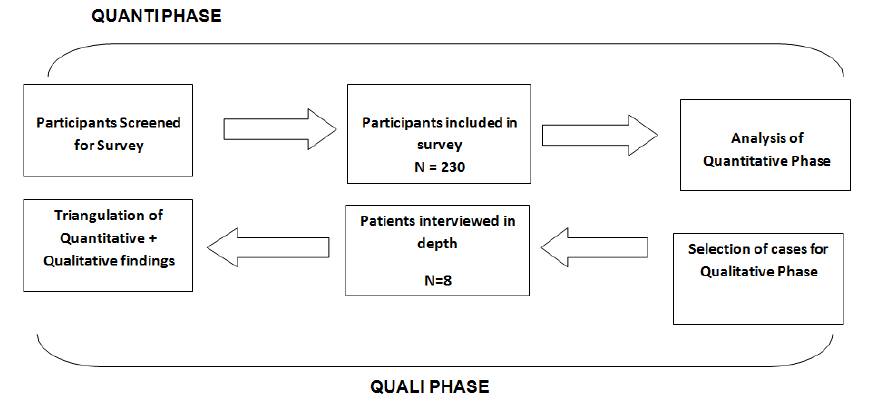

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram

Self-care in Heart Failure (HF) is essential to maintain Quality Of Life (QOL) and reduce hospital read missions. There are several factors affecting the self care among HF patients. To explore the Self Care Behaviors (SCB) and its influencing factors, a descriptive explanatory study a mixed method approach (QUANTI-quali) was employed. The SCB among HF patients was explored via a cross sectional survey whereas the influencing factors were explored through qualitative inquiry. The overall level of SCB was low with only 7% patients adhering to the desired SCB. The highest adhered SCB was taking medications (86%) whereas, the lowest was contacting physician for weight gain (10%). Moreover, patients' financial status, education, experience of the illness, family support, and self-control were the key factors that influenced the SCB of the patients. This study has implications for health care providers and policymakers to establish HF management programs for patients in our culture.

Heart Failure (HF) is defined as a progressively worsening clinical syndrome associated with high mortality and poor quality of life (QOL). Almost 25% of HF patients die within five years of their first hospital admission ( Stewart et al., 2001) while approximately 50% of the HF patients are rehospitalized within three to six months after discharge with the complaint of recurrence of symptoms ( Artinian et al., 2002; Krumholz et al., 2000; O'Connor, 2017).

However, it is believed that approximately one fourth of the HF hospital re-admissions are preventable, if patients adhere to recommended lifestyle changes, and seek early medical attention at the time when symptoms begin to appear ( Braunstein et al., 2003; Ziaeian and Fonarow, 2016). The most common reason for re-hospitalization among HF patients is non-adherence to prescribed regimen, which not only increases the number of hospital re-admissions, but also prolongs their hospital stay ( Wal et al., 2005). Therefore, recent guidelines by American Heart Association (AHA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) emphasize optimizing self-care abilities of HF patients, together with medications, to maximize life expectancy and improve the QOL of the patients ( McMurray et al., 2012; Jessup et al., 2009). A well adhered self-care regimen is reportedly associated with a happier, less depressive, and an empowered life because of improved clinical outcomes and reduced number of hospital re-admissions ( Artinian et al., 2002).

Self-care refers to a set of activities that individuals initiate and perform on their own, in the interest of maintaining health, continuing personal development, and well- being ( Artinian et al., 2002; Orem, 1985). SCB specific to HF includes adhering to the prescribed regimen of medication, exercise and fluid restriction, symptom monitoring (observing weight changes) and symptom management (seeking early medical help or taking an extra diuretic) ( Artinian et al., 2002; Braunstein et al., 2003; Riegel et al., 2009). Empirical evidence suggests that almost 21%-55% of hospital readmissions among HF patients are due to poor adherence to the prescribed selfcare regimen ( Braunstein et al., 2003; Heo et al., 2009; Ziaeian and Fonarow, 2016).

With the growing burden of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) in Pakistan, and limited health care resources, HF population needs to be prepared to take care of themselves. However, prior to initiating any self-care programs, the existing level of self- care behaviors among HF patients needed to be explored. Understanding of the shortfalls in HF specific to SCB, can help health professionals’ plan educative and supportive interventions for patients. Therefore, this study was undertaken to explore the self-care behaviors (SCB) among HF patients and factors affecting them.

Figure 1 shows a descriptive explanatory design with sequential mixed method approach (QUANTI-quali) was used for this study.

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram

The study was conducted at four private tertiary care hospitals of Karachi which had the facilities of non-invasive as well as invasive cardiac diagnostics and intervention services.

For the cross sectional survey, a nonrandom consecutive sample of 230 HF patients was recruited from the inpatient as well as outpatient cardiology units, between January 2013 and June 2013. Eligible patients were adult aged ≥18 years with established diagnosis of HF, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF <45%), living in Karachi, able to speak and understand national language, free from any untreated malignancy, and cognitive impairment. Patients were approached for their participation, at the time of discharge, or when they were waiting in outpatient clinics. The study’s purpose and procedure were explained to the eligible patients. Those who agreed and gave informed consent were recruited in the study. Similarly, for the qualitative inquiry, participants were shortlisted during the sur vey based on their score of SCB and other characteristics, including variation their age, gender, socioeconomic background, educational level, length of the HF diagnosis, and the type of the HF facility utilized (public or private).

Their availability for an interview was sought at the time of filling the survey questionnaire.

The European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior (EHFSCB) scale was used to assess the SCB of the patients ( Köberich et al., 2013). It is a 9-item tool that measures the level of SCB of HF patients on a Likert scale of agreement from 1-5 (strongly agree to strongly disagree). The lower the score, the better the self-care. The tool comprises two basic constructs; “consulting behavior” and “adherence to regimen”. Consulting behavior are the SCB which requires patients' conscious decision making for timely management of their HF symptoms whereas, adherence to regimen refers to the SCB that requires patients' consistency in performing the prescribed SCB ( Jaarsma et al., 2009). The validity and reliability of the tool has already been published widely ( Jaarsma et al., 2009). For the purpose of this study, each item on the tool was categorized into good SCB or bad in effective SCB. A score of ≤ 2 was considered good while a score of ≥2 was considered bad. Hence the overall score for desired SCB was ≤ 18 and for Undesired SCB, the overall score was >18 ( Kato et al., 2009). The tool was translated into the national language (Urdu), by a language expert. It was then sent to five cardiologists for content validation who rated each item of the tool on a scale of 1-4 for relevance and clarity. The Urdu version of EHFSCB tool was found relevant (CVI-R= 0.68), but some modifications were suggested to enhance the clarity of the tool. For example, it was suggested to add a question on how much fluid patients were allowed to drink and what kind of physical exercises they performed. The content validity index for clarity was then recalculated (CVI-C=0.70). In addition to that data on patients' demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained using the researchers’ prepared checklist. The tool and the checklist were pilot-tested on 13 patients who were excluded from the final analysis.

For in-depth interviews, a semi structured interview guide was prepared, considering the items in the EHFSCBs. The guide consisted of approximately 10 open-ended questions, which were designed to obtain an in-depth understanding of the each SCB performed by the HF patients. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. They were audio-taped and field notes were also taken during interviews to record the nonverbal clues of the patients.

The study commenced after approval of the hospital's Ethical Review Committee (ERC), [Ethical Review Number: 2421-SON-ERC-12]. Written informed consent for the survey as well as for the interview was obtained from all the patients who agreed to participate in the study. For confidentiality, instead of names, codes were used for participation in the survey. Similarly, pseudonyms were used to report qualitative finding.

All the survey data were entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0. Variables were assessed for normality distribution. Mean and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables following normal distribution whereas, median and interquartile ranges (IQR) were reported for variables following non-normal distribution, Proportions were calculated for the categorical variables.

The in-depth interviews were transcribed and verified with the recording, by the PI. The transcriptions were re-read and pertinent information from each transcript was collated according to the interview questions. Following the steps of content analysis according to Morse and Niehaus (2009), the aggregated data on each question was read; important words and phrases of the respondents were highlighted. The highlighted pieces of information were condensed and labeled with meaningful codes, such as 'facilitators' and 'barriers to SCB'.

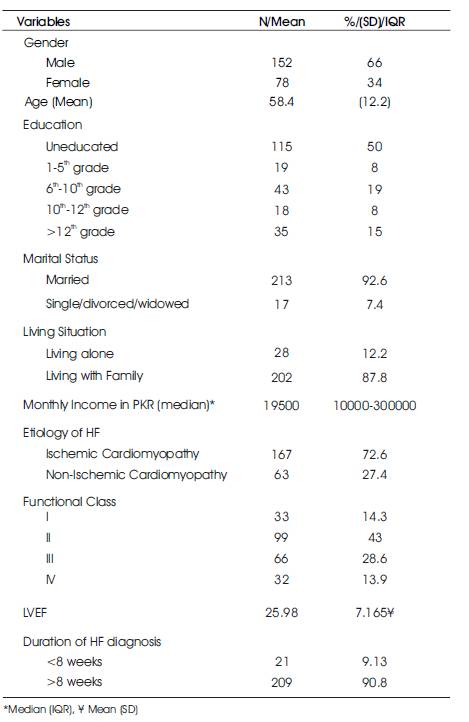

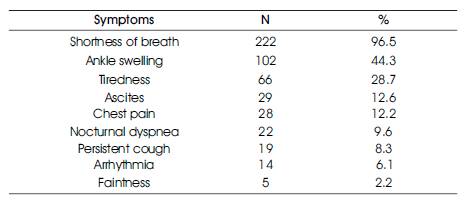

In Table 1, two-thirds of the study participants were male. The mean age of patients was 58.2 (12.2) years. Most of the patients were married and lived with their families. Ischemic cardiomyopathy was the reason behind HF of most of the patients. Majority of the participants belonged to functional class II and III as per the classification of New York Heart Association (NYHA) and were diagnosed for HF for >8 weeks. Most of the patients came to the hospital with the complaint of shortness of breath and ankle swelling (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 2. Reasons for Consultation

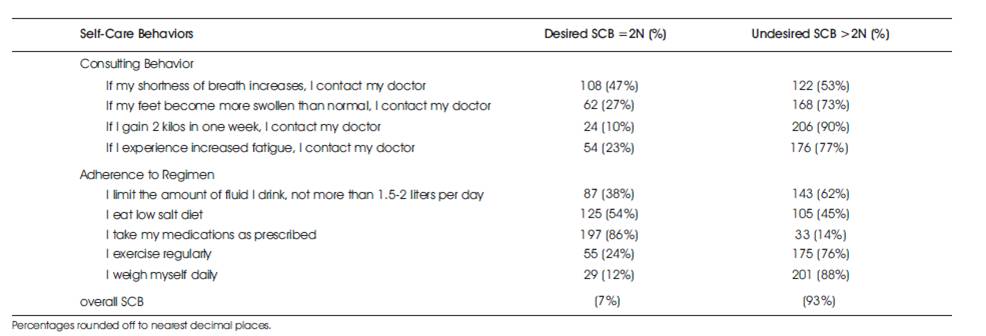

Based on the cutoffs defined for good and bad SCB, only 7% patients performed the desired level of SCB (Table 3). Regarding SCB, adherence to prescribed regimen was relatively higher than consulting behaviors.

Table 3. Adherence to SCB

Similarly, with respect to specific SCB, medication regimen was the highest (86%) performed behavior whereas, weight monitoring (12%) and contacting physician for weight gain (10%) were the least performed SCB.

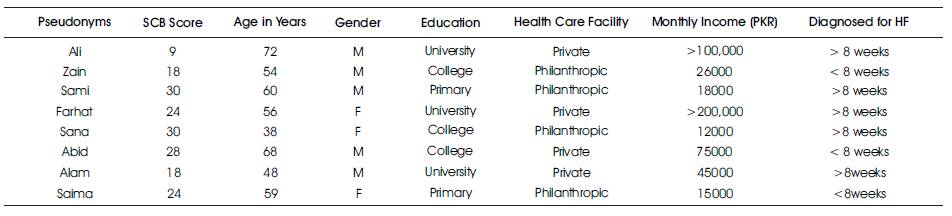

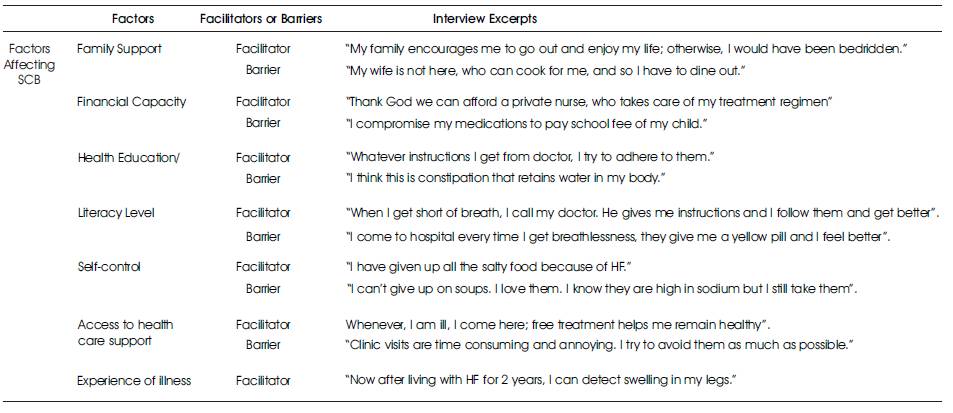

The characteristics of the participants of the qualitative phase are presented in Table 4. The analysis of patients' narratives revealed several factors (Table 5) that influenced the SCB of HF patients. These factors are discussed below with excerpts from patients' narratives.

Table 4. Characteristics of Study Participants in the Qualitative Phase

Table 5. Factors affecting the SCB

Previous episodes of volume overload and its related hospitalization emerged as a learning experience for the HF patients as it positively influenced them in symptom recognition and seeking help on time. Patients who had had prior hospitalizations due to congestive heart failure reported that they observed and learned skills of edema assessment and its management from the way staff assessed them during hospitalization. As Abid shared, “Doctors used to check my swelling by pressing over these (ankle) bones… I also check them that way at home.”

Similarly, with time, patients' alertness towards their symptoms increased and they began to consciously monitor themselves regularly, which enabled them to anticipate warning signs of symptom exacerbation, at an early stage. For instance, Ali explained, “… as my weight increased, I contacted my doctor, because it happened to me in the past that breathlessness appeared shortly after weight gain…” Hence, to avoid worsening of symptoms and hospital re-admissions, patients sought early medical help. Also, regarding the previous hospital experience; patients not only remembered their painful suffering, but also recalled how a quick access to treatment alleviated their agony; and that memory positively influenced their self-care.

The presence of family support, especially spouses, appeared to be a strong source of encouragement for all the patients, irrespective of their socioeconomic background and gender. Spouses were usually the first ones to notice changes in the breathing pattern and functional class of their husband or wife and notified them. They helped patients manage their illness by constantly reminding them about follow-ups and accompanying them to their physicians. Abid shared, “My wife recognized that I was breathing with difficulty… she immediately called Doctor X and fixed an appointment for me.” Spouses were also actively involved in purchasing, refilling, and reminding medication doses to their partners. As Zain said, “My wife gives me medications according to the prescription daily after dinner. She takes care of all the things.” Family members also provided emotional and tangible support by adapting the lifestyle modifications needed by the patients. As Abid mentioned, “Everybody in my family has switched to low salt diet now…, we don't use excess salt for anybody in the family”.

Patients appreciated the role of their spouses and family members and paid gratitude to them. Appreciating her family's support, Farhat said, “God give my husband long life and good health and also to my children….they have always been my support and source of encouragement in this illness.”

Absence of spouse and family members created a vacuum of support which negatively influenced SCB of some patients. Patients who lived alone had to manage their medication regimen, fluid restriction, and follow-ups themselves; they explicitly shared the need for help in managing their diet regimen.

As Sami verbalized, “If my wife had been living in Karachi, I would have asked her to cook fresh food for me, as per doctor's recommendations….” Hence, overall family support was reportedly an important factor that facilitated the SCB of the HF patients.

The financial status of the patients also emerged as an important factor in facilitating or constraining their SCB. The ability to afford medicines, necessary tools, such as weighing scale, access to private health care facility/professionals were possible for those who had strong financial status. Patients, who could afford the cost of private hospitals, visited emergency care services to get rid of the symptoms immediately. Although they were not proactive in their approach, their ability to afford care at any cost avoided delays, and they were able to seek the best medical help quickly and comfortably. As Farhat stated, “… I collapsed and was brought to this hospital, and Doctor X treated me; he is the best cardiologist of our country…” Similarly, availability of a private nurse improved patients' adherence to regimen behaviors, despite absence of any active efforts from the patients themselves. For instance, Farhat shared, “I have a private nurse…who gives me medications, the calculated amount of water, and takes care of my entire treatment plan.”

On the contrary, financial constraints were observed as a barrier to SCB. Lack of money significantly affected medication compliance, weight monitoring, and help seeking behaviors.

Expressing her financial worry, Sana said, “It is all about money. We have to pay bills and school fee of our child…. Eventually, I have to compromise my treatment.” Also, patients who could not afford a weighing scale did not weigh themselves regularly.

Being unaware of their weight gain, they ended up coming to hospitals with acute events of volume overload. Likewise, patients going to private hospitals for treatment also skipped their follow-ups due to high consultation fee, unless their functional status was severely compromised.

Another important factor that affected the SCB of the patients was health education. Comprehensive health education with clear written instructions and detailed explanations helped patients to remember and follow the recommendations correctly. Patients appreciated written instructions because they were able to refer them when needed. But written instructions were not commonly available. Additionally, health education helped patients prioritize their behaviors. For instance, awareness about the indication of diuretics helped patients recognize its importance and strictly adhere to its usage. Almost all the patients considered Lasix as the most important drug in their prescription and tried to remain compliant to its use in all circumstances. As Sana reported, “even if I don't have money, I try not to miss Lasix because my doctor told me that it is the most important drug on my prescription.” In contrast, lack of specificity and clarity in the health instructions contributed to poor SCB and raised questions in patient's mind, related to treatment regimen.

As Abid mentioned, “The doctor advised me to drink less water but did not tell me any specific amount; whenever, I drink water, I doubt how much to consume….” Patients who were unaware of the purpose of the specific SCB exhibited poor adherence to those behaviors.

For instance, Sami's sub-optimal compliance to medication regimen was a result of his knowledge deficit about medications which is reflected in his excerpt, “….I don't know what my medications are for. What do they do and what are their side effects. Only God knows and the doctor knows.”

Similarly, because of lack of knowledge, patients performed certain SCB (fluid and salt restriction) with estimation rather than accuracy. Five out of eight patients reported that they did not measure their daily fluid intake and consumed an estimated amount of fluid daily. As Sami answered, “I do not measure the amount of fluid that I take every day. I just consume an approximate amount of water and tea daily….” Likewise, most of the patients estimated the amount of salt in diet by merely tasting it, but did not measure its quantity.

Inadequate health education also developed misconceptions related to HF. As Farhat stated, “I think that constipation leads to water retention in my body. If I get rid of constipation, I may not develop swelling.”

It was found that a higher education status of the patients enhanced their ability for adherence to the prescribed regimen and consulting behaviors. Well-educated patients updated their knowledge from multiple sources, such as books and internet. As Ali shared, “I read somewhere that 5 grams of sodium is enough for a family for the entire dish… so I have instructed my wife not to put more than one tea spoon of salt in the entire dish.” Educated patients were also confident in contacting and discussing their disease status and its management regimen with their physicians as compared to their uneducated counterparts. Physicians too, allowed educated patients to adjust their diuretics to a certain extent. They could also follow the instructions of their cardiologists via telephone. For example; Ali shared, “When my weight increased 2 kilograms in one day, I contacted the doctor and he advised me to increase the dose of Lasix and decrease water intake....after following that I was alright.” Hence, patients with good literacy were in a better position to monitor and manage their condition which helped to control their disease and limited their hospital visits.

Unlike the above, patients with low level of education, expressed problems in understanding and following complex instructions. For instance, they verbalized difficulty in adjusting to the restricted lifestyle. As Sana expressed, “doctor advised me to take an extra Lasix whenever I have SOB. I just do not understand when to take it because I think that I may be getting breathless because of exertion, so I take rest but do not take extra pill, and go to doctor.”

Regardless of their socioeconomic status, educational status, health education, and finance, patients with strong self-control have had better adherence to diet and fluid restriction. Six of the eight patients reported that they modified their food choices according to the requirement of their health and strictly followed them. Commenting on his diet modifications, Sami shared, “If I dine out, I make sure that I eat only raw vegetables.” Similarly, about his thirst control, Zain said, “I used to drink four glasses of water only with food. But now I take only sips of water when I am thirsty and try hard not to go beyond the limit.”

However, temptation for salty foods, beverages, and water resulted in poor adherence to the regimen. As Farhat mentioned, “I have given up peanuts, saltish biscuits, and nimko for my heart problem [but]…. I cannot leave soups; I love them and I still take them,”

Similarly, Sami who is a security guard by occupation and works outdoors even in summer, shared, “Doctor has allowed me one liter of fluid every day but I consume more than that as my throat dries because of thirst.”

Additionally, among the patients whose SCB score >18, some of them reported that they sometimes ignore signs of water retention due to their household and job responsibilities. Hence, they continued their routine treatment and contacted their physician only when they became NYHA functional class IV. As Farhat stated, “I had developed swelling on my feet, but I was busy preparing for Eid and stuff…. so I just ignored it and suddenly collapsed on EID day.” Likewise, Sami reported, “Sometimes I become short of breath while working, but I have an outdoor job, I have to do my job. So I just take some rest and take medicines.”

In addition to all the factors discussed above, access to health care systems also greatly influenced the SCB of the patients. For poor patients, access to free tertiary care (philanthropic hospital) appeared as a facilitator for poor patients; it provided them access to free emergency, clinic, and laboratory services and thus helped them adhere to their consulting behavior without worrying about paying.

However, patients who utilized philanthropic hospitals reported that follow-ups with longer intervals (more than 3 months) delayed their help seeking and it was difficult for the patients to contact their doctors if help was required prior to the scheduled appointment. Likewise, all the participants, regardless of the facility, reported that clinic visit is time consuming due to which patients did not come to see their physicians frequently and visited them only when necessary. For example, Sana reported, “… it takes almost an entire day to see the doctor…. We reach home at night…. My husband has to take a day off from work to bring me here.”

Patients who used the private health care facilities also highlighted some limitations of the health care system, which negatively affected their SCB. These system constraints included unavailability and lack of communication by the primary physician, longer intervals of follow-ups, and time-consuming hospital visits. Reflecting on his experience of visiting his physician at a private health care facility, Abid stated, “in his [primary cardiologist's] absence…I was prescribed some different diuretics and blood pressure medicines by the assistant of the primary physician, which I did not follow, because I did not know him… although my condition worsened, I waited for 15 days until the doctor returned from vacation and rescheduled my visit…” Hence, patient rapport also contributed to his SCB.

The findings of this study provided valuable information regarding the SCB and its associated factors among HF patients in Karachi, Pakistan. The overall SCB in the present study was found to be poor. This indicates that self-care is relatively a newer concept in this population because in an Eastern culture, the role of a caregiver is strongly highlighted in managing the illness of family members.

With regards to the specific SCB, the findings of this study are in some ways like those reported in earlier studies on this topic. Like others ( Jaarsma et al., 2003; van der Wal et al., 2006), medication adherence was the highest performed SCB in this study. Medication is generally perceived as an easy solution to all health problems. Patients find written prescriptions authentic and inevitable because they are answerable to their physicians in subsequent visits. Therefore, medication adherence is generally high in other studies as well. In contrast with the high level of medication adherence, a low level of adherence was found for weight monitoring. Because these patients had not received any health education on self care, particularly weight monitoring, this was an expected finding. Similarly, keeping a weighing scale at home is not very common practice in Pakistani culture perhaps due to the cost of the weighing scale. This result is in line with the findings of a multi-cultural study conducted earlier by Jaarsma et al. (2013).

Consistent with the existing literature ( Riegel and Carlson, 2002; Woda et al., 2015), the authors also found that support of the family, especially spouse, contributed positively towards self-care. Similar to previous studies, the support was prominent in improving adherence to medications and low sodium diet ( Clark et al., 2014; Riegel and Carlson, 2002; Woda et al., 2015), and early detection of warning signs of HF exacerbation. However, caregiver support was limited in other aspects of HF self-care, such as weight monitoring and symptom management. One possible explanation of this finding could be the caregiver's and patients' knowledge deficit regarding HF management. Thus, family members extended their support in simple rather than complex behaviors. This was an important finding as it reflected the strong family support in Eastern culture. To specify, joint family systems and obligatory caring for older adults in the East makes family members an important part of patient's self-care regimen, which eventually helps improve patients' self-care.

Concurrent with the existing literature ( Clark et al., 2014; Dickson et al., 2008), the researchers also found that patients improved their self-care abilities through their experience of illness. The ability to learn self-care skills overtime and then incorporating them into their daily lives improved early detection and proactive help seeking behaviors of the patients. These findings affirmed the findings by ( Carlson et al., 2001; Dickson et al., 2008) who also reported that integration of HF self-care in daily lives, increased HF patients' adherence to SCB. The exploration of patients' potential to learn from the experience is an important finding in their context because of the lowest literacy rates. Hence, experience of illness can be utilized in the future to enhance patients' understanding of self-care skills.

The findings of this study also indicate that health education played a key role in improving the self-care abilities of the patients. Although patients in this study received informal health education, yet it was appreciated and reportedly had a positive influence on their SCB. This is inline with the findings reported by ( Shao et al., 2013), where patients valued informational support and linked it with improvement in their health status. A positive influence of health education on self-care is important in this context, because it indicates patients' receptivity towards formal HF education in future.

Similar to the findings of ( van der Wal et al., 2010) in Netherlands, they also found that inadequate support from the health care system, served as a key barrier to SCB among HF patients.

Usually those with low education have limited learning capacity so they need more help from the health professionals. But their access is limited to philanthropic or government institutions, which are usually flooded with patients. As a result, the interval between their follow-up visits lengthens. Meanwhile, these patients neither have the opportunity nor the confidence to speak to their physician and take action for early warning. Hence, these findings indicate the need for nurse-led supportive-educative HF self-care programs which provide educational as well as follow-up support to the HF patients to enhance their selfcare.

The study is unique because of its mixed method design which provided an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon through which different factors affect the SCB of the HF patients. However, a cross sectional survey design implies that no cause and effect relationship can be established between the variables ( Mann, 2003). Moreover, this study did not explore the role of informal caregivers on self-care of HF patients, or the quality of life of HF patients. Hence to plan targeted interventions in the future, further research studies on quality of life and its associations with self-care behaviors are required.

This mixed method study explored the level of self-care and its associated factors among HF patients in Karachi, Pakistan. The findings of the survey showed that in general patients had low adherence to the desired SCB. The findings of the qualitative exploration revealed that family support, health education, self-control and support of the health care systems are key factors influencing the SCB of the HF patients in Pakistan. The information about self-care and its associated factors can be utilized further to develop interventions to optimize self-care among the HF patients in our culture.

SCB - Self Care Behavior

HF - Heart Failure

QOL - Quality of Life

AHA - American Heart Association

ESC - European Society of Cardiology

CVD - Cardiovascular Disease

LVEF - Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

EHFScB - European Heart Failure Self Care Behavior Scale

CVI - Content Validity Index

CVI-C - Content Validity Index for Clarity

CVI-R - Content Validity Index for Relevance

ERC - Ethical Review Committee

SPSS - Statistical Package for Social Sciences

IQR - Interquartile Ranges

NYHA - New York Heart Association

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this editorial.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this editorial.

AG conceived the study design, prepared protocol, looked after all the aspects of the study. Validated the tool, conducted in-depth interviews, analyzed quantitative as well as qualitative data and prepared manuscript. RG supervised AG in all aspects of the study from protocol development till manuscript writing. SD provided content expertise and administrative assistance for data collection.