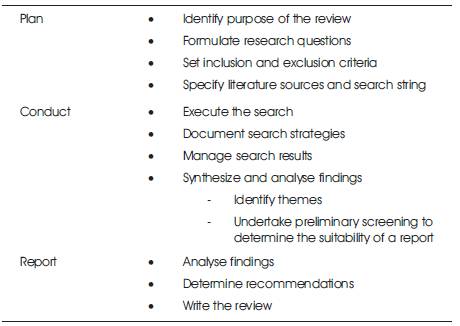

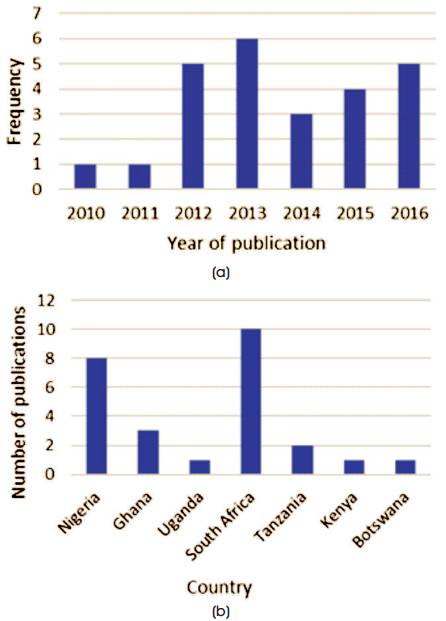

Table 1. Steps followed in Conducting the Systematic Review

Despite the huge penetration of mobile technology in Africa and its wide adoption in the region for communication, business and entertainment, its use in education is not widespread. To investigate this problem within the context of higher education, a systematic review of articles focused on adoption and implementation of mobile learning in Africa published from 2010 to 2016 was carried out. The literature search showed a growing trend in mobile learning research in Africa, however, only a handful of these had practical implementation indicating that despite the growth of m-learning studies in the region research into practical implementation is still very limited. Nevertheless, this review identified trends in the adoption studies, modes of implementation, and reported barriers to implementation. Subsequently, the barriers were grouped into five categories and sub-categorised into most frequently reported, frequently reported, and infrequently reported. Despite the paucity of the latter, they were still considered central for effective implementation. Analysis of this snapshot of m-learning implementation in African universities led to the development of recommendations to overcome reported barriers and thus makes a useful resource for policymakers and those considering adoption.

Mobile technology has spread at an unprecedented pace across the globe in recent years. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, 2015) 95% of the world's population live in an area that is covered by a cellular network. About 830 million young people, representing 80 per cent of the youth population in 104 countries have access to the internet using mobile devices (ITU, 2017). The continuous progress of mobile technology and portability of mobile devices has broadened their use in almost every sphere of human existence, including the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge in Higher Education (HE). Traditional learning was first advanced electronically using e-learning (Fadare et al., 2011), but as mobile technology evolved, mobile devices have become ubiquitous, making learning with them potentially even more revolutionary than e-learning (Alrasheedi, Capretz, & Raza, 2015). More so, it is argued that two unique features of mobile learning (m-learning): mobility and collaboration give the learner flexibility to learn at their own time, place and pace and the opportunity to interact with other learners and educators from different locations (Ally, 2013; Pegrum, Oakley, & Faulkner, 2013).

The literature suggests that virtually all students in HE have at least one mobile device which they check at least once every six minutes (Educause, 2011). While this indicates students' dependence on their mobile devices, their use for learning is not as widespread as the devices themselves (Alrasheedi et al., 2015; Dahlstrom, Brooks, Grajek, & Reeves, 2015). Some researchers argue that technical competence, development of assessment techniques, and institutional support could be factors affecting the slow adoption rate of m-learning in HE (Alrasheedi et al., 2015). Notwithstanding this, there is a substantial body of research investigating mobile learning in HE conducted in advanced countries with bulk from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Taiwan (Wu et al., 2012) .

A study by Tsinakos (2013) on the state of m-learning in the world found that several m-learning projects have been implemented in developed countries to enhance university teaching and learning. This includes transforming web pages into formats suitable for mobile devices in the United States, having dedicated space for mobile computing devices to facilitate collaboration amongst students and academics in Canada, and several iPad projects in Australia. However, only few m-learning projects were identified in developing countries with focus mainly on children in primary and secondary schools, support for learning English language and increasing literacy levels (Tsinakos, 2013), which contrasts with the situation in the developed world where universities are well considered. Studies conducted in developing counties particularly in Africa are few compared to the advanced world, even so, most of these studies are fragmented and focused more on intentions to use rather than actual implementation (Kaliisa & Picard, 2017; Lamptey & Boateng, 2017). This strongly suggests that there is scope to undertake further investigation that focus on adoption and implementation to determine the level of penetration of m-learning in African HE. As such, this study conducted a systematic literature review to: (1) identify studies that focus on adoption and implementation of m-learning in HE institutions in Africa; and (2) analyse and synthesize these findings to identify trends in the adoption of m-learning, the reported benefits and barriers to implementation.

The next section presents an overview of previous systematic reviews. Followed by the methodology used for this study in section two, results and discussion in sections three and four. The identified gaps and future research directions in section five, study limitations in six and finally the recommendation and conclusion in sections seven and eight respectively.

A significant body of diverse literature exists with respect to reviews on m-learning. The works of Saleh and Bhat (2015) and Wu et al. (2012) in their respective reviews found that the most investigated aspects of m-learning research are the effectiveness of m-learning, system design and analysis of the learners' characteristics; with surveys and experimental methods as the most commonly used data collection methods. Most studies were from higher education environments, particularly universities in language and linguistics courses followed by IT related courses, with PDAs and mobile phones as the most commonly used devices. Likewise, Hung and Zhang (2012) investigated the clusters and domains of m-learning, publication dates and predominance of topic by country, institution and journal preferences. Their findings show an increase in m-learning research over the years and suggest that m-learning is at the early adopters' stage. The work of Alrasheedi, Capretz, and Raza (2015) focused on identifying m-learning critical success factors from the students' perspective. Findings were drawn from 30 studies conducted in 17 countries indicating that learners' perception is most critical for success and that collaboration, ubiquitousness, and user-friendly designs are seen by students as the greatest advantages of m-learning. While these reviews focused on m-learning from a global perspective, other reviews such as that the works of Lamptey and Boateng (2017); and Kaliisa and Picard (2017) have focused on m-learning in developing countries and Africa, respectively. Their findings indicate that the application of mobile devices in education is still at its fancy, and although the area of m-learning is increasingly being researched in Africa, the focus has mainly been on how m-learning can be used to improve educational outcomes. Majority of the studies related to adoption have focused on ownership of appropriate devices for m-learning and willingness for its acceptance with very few studies on actual implementation. The reviews did not explicitly capture the level of penetration of m-learning in Africa with regards to establishing intentions to adopt and actual implementation as well as the modes of implementation. Therefore, there is need for a systematic review that identifies the adoption trends, level of practical implementation, and modes of implementation; and brings together the strengths and weaknesses from practical experiences to guide future adopters and increase the practice of m-learning in higher educational institutions in Africa. Such a review would help identify the factors critical to the successful implementation and sustainability of m-learning in African universities. To achieve these goals, this review is guided by the following research questions:

a) Research distribution;

b) The participants and how their perceptions were collected;

c) The focus of study and;

d) The underpinning theories?

To ensure a transparent and comprehensive study it was necessary to follow critically reviewed and established guidelines. Therefore, this review was conducted following suggested approaches by Okoli (2015) and Ramdhani, Ramdhani, and Amin (2014). Okoli (2015) provided a useful starting point and sophisticated account of systematic literature review methodology, while Ramdhani, Ramdhani, and Amin (2014) provided step-by- step guidelines to analyse, synthesize, and report the findings. Together this led to the development of a review process using three major steps: plan, conduct, and report (see Table 1 for a breakdown of each step).

Table 1. Steps followed in Conducting the Systematic Review

The process started with a comprehensive search to find suitable studies from electronic databases, such as Google Scholar, Educational Resource Information Clearinghouse (ERIC), Association of Computing Machinery (ACM), Scopus, and Science Direct. These were chosen because they are popular databases believed to include relevant articles for this review. To ensure a more exhaustive search it was necessary to also search relevant journals with focus on Africa. As such the search was expanded to include journals, such as the Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries (EJISDC) and the International Journal of Education and Development using ICT (IJEDICT). It was decided to limit the selection of studies to peer reviewed articles published from 2010 because previous reviews showed reasonable increase in the number of studies from 2010 indicating that m-learning is still an emerging research area. For example, the review by Wu et al. (2012) showed only one article published in 2003 and 50 in 2010. Likewise, Kaliisa and Picard (2017) indicated that there has been a continuous growth of the mobile technology in Africa since 2010.

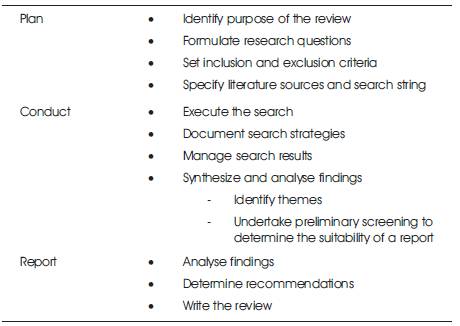

The initial search was conducted using the keywords “mobile learning” AND “higher education” AND “Africa” OR “developing countries”. This produced 30,200 results from Google scholar 132, 457 and 1960 results from ERIC and Scopus, respectively. To make the systematic review more manageable the search was subsequently restricted to titles, keywords, and abstracts. This brought the total number of papers from all sources to 798. To further narrow the search, rather than immediately reducing the search focus, a number of preliminary screening processes were conducted. The first preliminar y screening narrowed the studies to those focused only on HE in Africa (i.e. excluding other developing countries). This reduced the number of studies to 357. The next phase required removing duplicates and studies considered “vague”: i.e. studies not solely focused on m-learning; studies not specific to any country or HE in Africa; and those not focused on any group of stakeholders. This brought the number of studies to 54. The third stage of the preliminary screening involved removing studies that were not based on adoption or implementation of m-learning; reducing the number to 32. The final preliminary screening removed studies where primary data was not collected bringing the total and final number of studies to 25. A more comprehensive account of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Literature Selection Process

This section presents the results of the 25 peer reviewed articles used to answer the research questions (RQs).

RQ 1: What are the major trends of m-learning adoption in Africa?

In answering RQ 1, the trends have been categorised into: (a) research distribution by country and year of publication; (b) focus of study; (c) data collection methods; and (d) the theoretical and pedagogical considerations of each study.

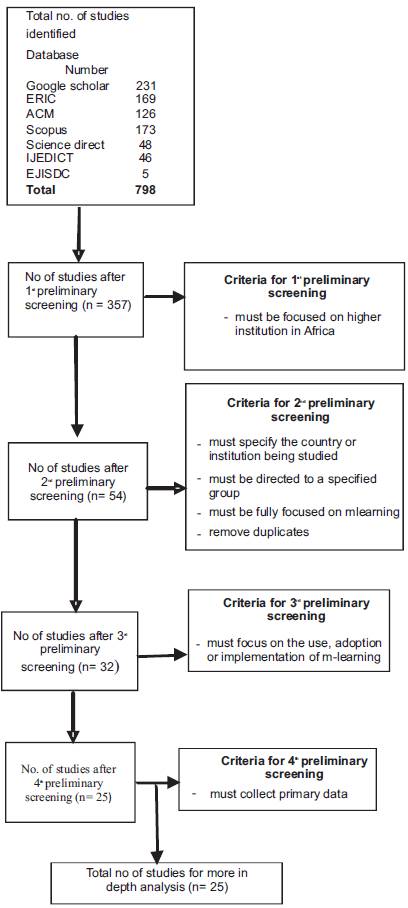

Figures 2 (a) and (b) show the frequency of publications over the years from 2010 to 2016 and the number of publications from each country. South African authors have the highest number of publications, with 10 articles out of the 25, Nigerian authors have eight, while authors from Kenya and Botswana have one article each. An increase in the number of publications is seen in 2012 and 2013 compared to 2010 and 2011 with five out of the six studies published in 2013 having some form of trial implementation. Although negligible, there was a decline in 2014 and a steady increase in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

Figure 2. Research Distribution of m-learning Adoption studies in Africa by (a) Year of Publication and (b) Country

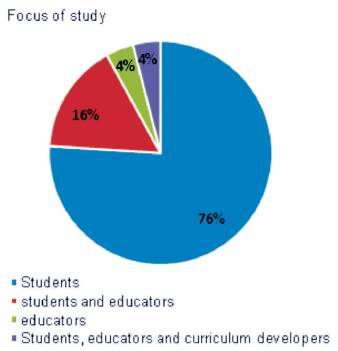

A total of 5851 students and 177 educators (including curriculum developers) were represented in all the studies. As seen in Figure 3, 76% of studies were centred on the student demographics, 16% considered students and educators, and 4% considered only educators. Only one study considered other stakeholders such as curriculum developers. Stakeholders such as university management and technical support staff were not considered in any study.

Figure 3. Focus of m-learning Research

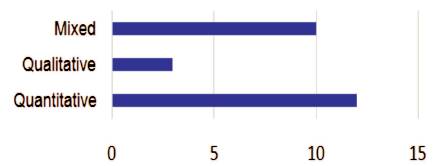

The most commonly used approach to collect data as identified in Figure 4 shows a preference for quantitative data (12), followed by mixed methods (10). A single qualitative approach was evidenced in only three studies. The most commonly used quantitative method was the use of questionnaires while the qualitative approach was mainly semi-structured interviews. Of the 10 studies that used mixed methods, five used questionnaires and interviews, three were based on questionnaires and focus groups, and the others utilized questionnaire, focus groups, and interview.

Figure 4. Methods of Data Collection

Given that m-learning is a technological innovation and the selection criteria used for this systematic review included journals with a technology focus is reasonable to assume that information technology theoretical frameworks, such as Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance and use of Technology (UTAUT), and Diffusion of Innovations (DOI) theories would be identifiable. Similarly, one would expect to find m-learning research underpinned by learning theorised as an active construction of knowledge. Given this, two categories of frameworks were employed as part of the in-depth analysis for this review: pedagogical and theoretical frameworks. Studies guided by learning theories were considered pedagogical frameworks while all other theories are grouped together under the theoretical framework category. As seen from Table 2, of the 25 studies reviewed, 15 used at least one framework of which only five studies were guided by learning theories (pedagogical frameworks), 10 by theoretical frameworks, and 10 studies were not guided by any frameworks.

Table 2. Pedagogical and Theoretical Frameworks

RQ 2: What is the extent of m-learning adoption and how is it being implemented?

This section presents the rate of implementation and the modes by which they have been carried out.

Of the 25 studies reviewed only 12 (representing 48% of the reviewed articles) had some form of practical implementation. Most of the studies were based on the intention for adoption and implementation of m-learning.

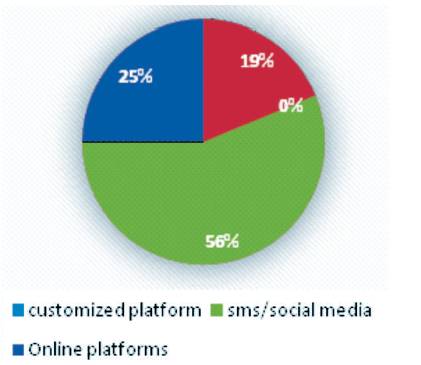

As shown in Figure 5, nine of the 12 articles explored m-learning using either only SMS or a combination of SMS and social media forums particularly 'WhatsApp' and

Figure 5. Mode of m-learning Implementation

'Facebook'. Only one study used 'Edmodo' (a social learning network strictly for educational purpose). Four studies used online platforms-two of these used podcasts, one used both 'YouTube' and 'Google Docs', and the last used pre-installed eBooks in tablets provided to lecturers by the institution. The last category of articles used customized platforms specifically developed for the m-learning project.

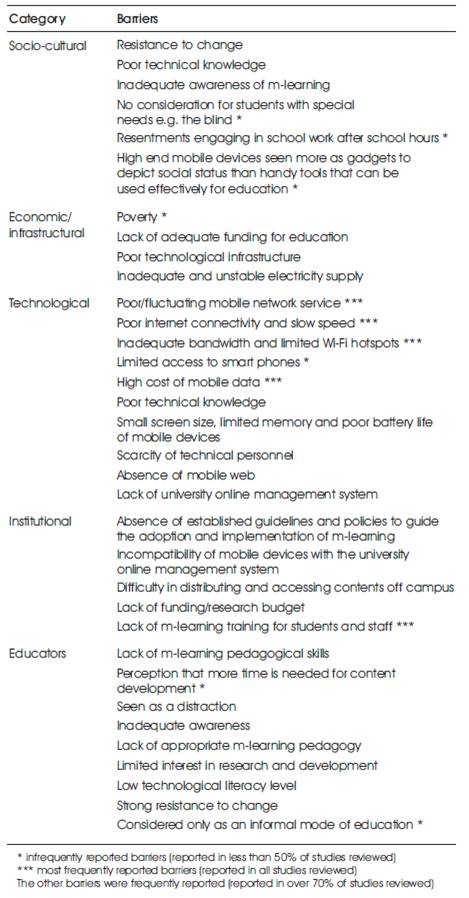

RQ 3: What are the barriers of implementing m-learning?

The barriers of m-learning illustrated in Table 3 were identified from studies where m-learning was implemented. While there were differences in terminology used to describe the downside of the m-learning experience, such as 'limitations', 'constraints', 'challenges', and 'difficulties', they have all been identified as barriers. A total of 33 barriers were identified, five of which were reoccurring in all studies indicating their severity and suggests the need for urgent attention if m-learning is to be successful in Africa. This study went on to group the barriers into five categories: socio-cultural, economic and infrastructural, technological, institutional, and educators. For contextual clarity, a brief explanation of each category is given below:

Table 3. Barriers to m-learning in Africa

This section discusses the key findings from the 25 peerreviewed articles that met the selection criteria for this study and consequently provided answers to the RQs.

The trends in the m-learning adoption studies were classified into research distribution by country and when these were published, the focus of each study, and how participants' responses were collected in addition to the theoretical representation of each article. It was gathered that South African authors had the highest number of publications. This could be attributed to that fact that South Africa is more advanced than other African countries and as such has better technological infrastructure, greater awareness of m-learning, and consequently more m-learning projects. The slight decrease in the number of studies after 2013 could be attributed to changes in research interest. Even so, this may not be conclusive because of the limited number of studies that met the selection criteria (25) in comparison to the total number of studies found (798). Preference is seen for the use of questionnaire over interviews to get responses from participants, this could be attributed to the ease of using this technique in gathering large sample of data against interviews that is more difficult and requires more time to analyse when used for large samples, in addition to being more expensive to conduct. These findings are consistent with other studies ( Kaliisa & Picard, 2017; Lamptey & Boateng, 2017). Another trend observed is the focus on students and the neglect of other stakeholders. Although it is argued that students are central in the educational process and the outcome of any meaningful educational outcome should be student-centred, the roles of other key stakeholders such as the institution's management and IT support personnel should not be neglected in technology adoption. This is a significant omission in the literature. Ng and Nicholas (2013) argue that in bringing new technologies such as m-learning to educational institutions, the management administration and leadership play a vital role in ensuring educators and students readiness, as well as the sustainability of the initiative. Likewise, the interaction between stakeholders, such as students, educators, curriculum developers, management and technical support influences the outcome of an m-learning initiative and having a dedicated technical team to support the process is vital for success (Ng & Nicholas, 2013).

Regarding the use of theory to guide m-learning implementation, Ozdamli(2012) argues that despite being a technological innovation, using the mobile technology for learning should be based on pedagogical considerations. However, this has not been the case as demonstrated in Table 2 where only five studies were guided by pedagogical frameworks. While there is no consensus on which theory is most suitable for m-learning, mobile learning principles rising from theory builds the foundation for meaningful learning outcomes (MacCallu & Parsons, 2016) . Likewise, our understanding and interpretation of the social world is meaningless without theory and learning theories provide the pedagogical basis for understanding how learning occurs(Ozdamli, 2012). Despite the view that theory is essential to understand the world of the learner, this systematic review has found that many studies lack such grounding. The lack of adequate theoretical underpinnings may be attributed to the absence of theory development by scholars in the African region which Lamptey and Boateng (2017) attribute to the learning context. They assert that most existing theories are framed by advanced societies and given that the context in advanced countries differs significantly from Africa, the available theories may not be suitable for the heterogenous nature of the African continent. This makes it clear that suitable theories that support the adoption of m-learning in Africa are needed. While it would appear that m-learning in African universities is embryonic, it is definitely gathering momentum. Importantly, however it also suggests that to move forward it is necessary to develop a framework that bridges technology and learning suitable for the specific m-learning context of Africa. To generate such a theory there is need for a deep understanding of all stakeholders supporting a top down and bottom up approach.

Despite that only studies focused on adoption and implementation were considered for this review, only 12 of the 25 articles reported on practical implementation. The other studies were based on intentions to adopt or implement m-learning. This indicates that research into practical implementation of m-learning is very limited in Africa in comparison to the developed world despite being at par in the level of adoption of the mobile technology as demonstrated by a study from Pew research center, the study found that an average of 80% of the adult population in Africa own mobile phones in comparison to 89% in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2015) . Of the few implementations reported, preference is seen for the use of SMS and social media platforms, only three studies had a customized platform (Figure 5). Notable of these projects is the 'AD-CONNECT' m-learning platform implemented in Ghana (Annan et al., 2014) . The one year pilot project tested the design of a learning platform intended to be robust and compatible with different mobile devices. It began by providing academics with professional learning on using the platform after which they were required to upload learning materials which students accessed using their mobile devices. The result saw m-learning as a valuable augmentation to traditional learning.

Concerning the reported barriers to implementation, this study found a total of 33 barriers which were grouped into five categories and further sub-categorised into: infrequently reported, frequently reported, and most frequently reported (see Table 3). The infrequently reported barriers are those reported in less than 50% of studies reviewed. Despite only appearing in a few studies, this study strongly suggests that the barriers still need to be addressed for successful adoption, these are represented in Table 3 with a single asterisk symbol (*). The most frequently reported barriers, those barriers which are mentioned in all studies are represented by three asterisks (***). Over 70% of the reported barriers fell under the frequently reported sub-category which is indicated by the absence of a symbol. It is clear from this analysis that all studies struggled with technological barriers, such as the high cost of mobile data; poor connectivity and slow speed of the internet; inadequate bandwidth and limited Wi-Fi hotspots; and fluctuating mobile network service especially during rainy season (Adedoja & Egbokhare, 2013) . The assumption that the wide adoption of mobile technology in Africa would make it easy to integrate m-learning into teaching (Ferry, 2009) turned out not to be so true as several studies reported that support for how to use mobile devices for learning for both academics and students was a key missing requirement (Adedoja & Egbokhare, 2013; Akeriwa et al., 2015; Mtebe & Raisamo, 2014; Tagoe & Abakah, 2014). Although most studies reported a positive attitude towards m-learning overall, inadequate ICT skills and lack of awareness of m-learning were widely reported. A poor awareness of and a lack of m-learning pedagogical understanding, as well as poor technological literacies of academics were frequently reported in the educators' category. While some educators were happy to explore m-learning, others strongly opposed its adoption claiming the use of mobile devices in the classroom would cause distraction and were suitable only for informal learning. There were also claims that the adoption would require more work and there were no incentives to motivate educators to take on the challenge (Adedoja & Egbokhare, 2013).

This systematic review has found that the majority of m-learning studies are unidimensional, interested by, and large in the perceptions of students. Although students are central to m-learning initiatives, the importance of other stakeholders (educators, management and administration, and IT staff) should not be underestimated. This follows the advice by Ng and Nicholas (2013) who assert that the interaction between all stakeholders and the technology is crucial for success. Moreover, communication between management, academics and IT units helps to create a trusting and conducive learning environment (Salmon & Angood, 2013). In addition, a strong interpersonal relationship between academics and students established through student-to-teacher collaboration will help students to value learning with mobile devices. For sustainable m-learning initiatives in higher education, future investigations should consider the opinions of all stakeholders.

The limited number of studies with practical implementation shows that m-learning research in Africa needs further exploration. Although inadequate funding, poor infrastructural and technological developments, and the high cost of mobile data are sad realities in Africa and have been identified as major barriers in implementing m-learning in the reviewed studies. There is evidence that some African countries such as Kenya have found a way around some of these challenges, through the use of basic cell phones that do not require extensive use of mobile data. Kenya is considered the hub of mobile technology in Africa because of its leading mobile app revolution and the use of basic cell phones to impact positively in the lives of locals (Murugesan, 2013). Most notable of these innovations is 'M-pesa', a mobile banking platform used for money transfers and other transactions regardless of whether the recipients have bank accounts. Others include: 'mHealth' for treatment and medication advice; 'Ecofarm' and 'mFarm' customized to send farming tips, market prices and weather report to farmers (Murugesan, 2013). In the educational sector, 'Eneza education' targeted at school aged children uses SMS to improve students' learning. The service is available at very low cost thereby making it easy for students, even in rural communities without access to smartphones and internet connections to learn (Isaacs, 2012). While it is acknowledged that HE may be more complex because of its perceived role to drive economic development (Douglas, 2005), research that considers how m-learning can be integrated and sustained into Africa's HE despite the continent's unique challenges is imperative. Moreover, for such investigations to be valuable the research should consider pedagogical and theoretical frameworks suitable for the heterogenous nature of Africa.

While the review was methodical and well grounded, it only represents a snapshot of m-learning studies in Africa because of its focus on the adoption and implementation of m-learning in universities, and only when studies collected primary data. These criteria helped to identify interesting insights into the adoption and implementation of m-learning in African universities from participants' points of view. The search for relevant articles restricted to titles, abstracts and keywords may have omitted studies which lacked the keywords but still focused on adoption and implementation in some form.

Guidelines for the successful implementation and integration of m-learning in HE in Africa are needed to replicate the reach of mobile technology found in sectors such as banking and the opportunities for learning in Kenya. Having policies that situate m-learning as a core technological requirement in HE could facilitate the increased use of technology in the system. In addition, raising awareness of the ability of mobile devices to be used as effective educational tools without necessarily being a distraction to learning and teaching as perceived by some educators would also help. Disseminating research outcomes of the few available successful implementation and integration projects and encouraging educators to experiment, document and share their findings irrespective of the outcomes should assist in avoiding the pitfalls encountered by earlier studies. Knowing this will allow the intrepid professionals in HE to build on the strengths of others hopefully resulting in the incursions they make into the implementation of m-learning more successful.

This systematic review has reported the state of m-learning adoption and implementation in African universities and despite the identified barriers virtually all studies of implementation reported positive outcomes. Importantly for Africa, mobile phones have shown evidence of great potential to be reliable instructional tools that can be used to achieve feats hampered by technology divide and the limitations of physical classrooms (Mayisela, 2013; Utulu & Alonge, 2012). One important and widely reported enabling factor is that students showed positive attitudes towards m-learning. The convenience and flexibility that m-learning reportedly provides was also seen to improve the value of face-to-face teaching and learning (Annan et al., 2014). However, while communication between all stakeholders is paramount, the relationships have been neglected and professional learning programs for participants have not been adequately considered.

We wish to thank Dr. David Baxter for his valuable comments that helped improve the initial draft of this paper.