Figure 1. Skeuomorphic vs Flat Design (Serianni, 2014)

With increasing popularity of touchscreen phones, there is a corresponding increasing emphasis on ergonomics considerations with a focus on use and interaction style between older and younger users. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the use of touchscreen phone interfaces to discover if they are designed to be inclusive and consider ergonomics. The research methods comprised interviews and focus groups in order to gain qualitative data on the use and satisfaction of touchscreen phones in relationship to age. Results have demonstrated a variety of opinions among the age groups, with users in the 18-25 age-range promoting a positive attitude towards brands, but blaming technology for errors, in contrast to users in the 60-70 age range who blamed themselves for errors and were more focused on function than brand. The study has gone some way towards enhancing our understanding of the attitudes surrounding inclusive design in relation to touchscreen phones.

This research investigates the use of touchscreen interfaces in order to understand if the ergonomics have been considered and whether they've been designed to be inclusive of all ages of users. A number of subjective and objective experiments were undertaken to analyse the differences between young technologically confident users and their older counterparts. The aim of this work was to evaluate the use of touchscreen phone interfaces to discover if they are designed to be inclusive and consider ergonomics with a particular focus on the use of the QWERTY keyboard. The aim was achieved through fulfilling the following objectives.

Evidence suggests that inclusive design is among one of the most important challenges for designers that more than often is ill-considered. Clarkson (2003) identified an inclusive approach as expanding the target user-group to include as many people as possible, removing the focus from age or disability and placing it on inclusivity at a social level without stigma. Similarly, Newell & Gregor (2000) found that user-centred design shifts the focus onto the users, giving disabled people the dignity of being treated in the same way as any other product user. Further to this, a broader perspective was adopted by Newell (2003) who argued that a true 'design for all' philosophy would imply that mainstream products would cater for the needs and capabilities of all users, which is an “impossible dream”. While a variety of definitions of the term have been suggested, this research used the definition suggested by Pattison and Stedmon (2006) who saw it as “inclusive design aims to cater for as many users as possible and therefore incorporate diverse user requirements - it is more of a design philosophy than an end product”.

Inclusive design is of interest because it raises questions about restrictions in the design of products. Nicolle & A Bascal (2001) were concerned that they can be seen as too restrictive by innovative designers, so instead a designer may draw from inappropriate design advice without questioning its validity. They expressed further concerns that frequently, it is also true that design recommendations are conflicting, not only between different sets, but also within the same set of guidelines demonstrating a lack of consistency (Nicolle & A Bascal, 2001). Newell & Gregor (2011) argued that inclusive design has been valuable in laying down some important principles and raising the profile of disabled users of products. They then concluded as 'design for all' is rarely achievable, designers often provide accessibility options, making the system more accessible, but do not consider the usability of the system. Together, these studies indicate that inclusive design remains an issue. In view of all that has been mentioned so far, one may suppose that the future innovations need to consider inclusive design in more depth. The past decade has seen the rapid development of touchscreen devices in many product design innovations. Investigating this further may provide insights into inclusive design in relation to touchscreen devices.

Touchscreens are an increasingly important area in design innovations despite having been used in electronic products for over thirty years. More recently, literature has emerged that offers contradictory findings about interface features. Balagtas-Fernandez, Forra & Hussmann (2009) identified the success and popularity of touchscreen devices by the use of simple features and good user experience (UX) design. Pickering (1986) suggests that touchscreens might still meet users' expectations, even if they have not been ideally designed. Contrastingly, in a study which aimed to improve upon the design of touchscreen keyboards, Sears (1991) showed results of users typing 25 words per minute (wpm) with a touchscreen, compared to 17 wpm with a mouse and 58 wpm with a keyboard. In view of all that has been mentioned so far, there seems to be some evidence to indicate that touchscreens are not as efficient as perceived. This view was supported by Scott and Conzola's (1997) study on designing touchscreen numeric keypads, writing “Existing design guidelines for touchscreens are applicable to only specific classes of devices and fail to consider user variables such as finger size”. Scott & Conzola (1997) argued that usability and human factors have not been considered when designing.

Traditionally interfaces were used to replicate physical products, but recent developments have seen the emergence of a trend classed as flat design. Serianni (2014) identified flat design as emphasizing usability by using minimalist design features such as bright colours, crisp edges and two dimensional flat structures. Further to this, he discussed the original skeuomorphic design style, shown in Figure 1, which used realistic textures, glossy buttons and shadowing. It was noted that users enjoyed interacting with imagery that may be related to their lives, presenting the skeuomorphic style as inclusively designed. However, many were sceptical of this style as designers believed that if a digital platform is separate from reality, then the interface design should replicate this, hence the emergence of flat design (Serianni, 2014). Hornor (2014) presented an account that argued the introduction of flat design excludes users, with two main complaints stating that they are too confusing and not intuitive enough. Frustration came with the lack of visual clues; with flat designs “relying too much on the minimalism and neglecting the usability”.

Figure 1. Skeuomorphic vs Flat Design (Serianni, 2014)

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in Apple branded products. The iPhone is a cause of concern due to the inclusive design debate of utilizing the latest flat design trend. Central to the entire discipline of touchscreens is the concept of human factors. People interact with touchscreens, therefore highlighting a need to evaluate the ergonomic issues of using a touchscreen device.

The issue of ergonomics has been a controversial and much disputed subject within the field of touchscreen design. The size of the phone is one of the most frequently stated problems with touchscreen devices. Fingas (2013) discussed the expanding phone size, using examples of extreme phone screen size stretching the limits of human hands, causing many to take a two-handed approach to smart-phone use. According to Lee, Yun, Jung & Freivalds (1997), too frequently products are developed with the attitude that human needs and characteristics are a separate issue. Conversely, Lin (2013) reported positive recognition of larger touchscreen sizes, with a lower error and fatigue rate, especially in those with larger hands. However, users with smaller hands took longer to operate in order to maintain smart-phone stability. Considering all of this evidence, it seems that there is still room for discussion around the effects of phone size.

The size of fingers in relation to button size continues the debate. A recent study on the effect of thumb sizes on texting satisfaction by Balakrishnan & Yeow (2008) , concluded that varying thumb sizes in length and circumference correlates to positive or negative satisfaction when texting. Accidentally hitting the wrong keys was a common occurrence with those with larger thumbs, causing dissatisfaction with key size and spacing, while those with smaller thumbs often suffered from strain when trying to reach keys further away. The studies presented thus far provide evidence that ergonomic principles haven't been fully considered when designing, as can be seen in Figure 2, demonstrating the size of the thumb in comparison to the phone.

Figure 2. Thumb Texting (Spencer, 2014)

One of the most significant current discussions of touchscreen devices is if they are inclusive or exclusive of groups of users, such as our ageing population. In their survey, of how age affects capability and attitudes towards technology, Langdon, Lazar, Heylighen & Dong (2014) identified that age has a moderate correlation, but education level was the most significant. They commented that people with lower education levels may find screen layouts confusing; recommending that designers consider the intended users when designing screen layouts. This demonstrates the need for separate designs for different groups of users. Conversely, Burrows, Mitchell & Nicolle (2011) reported that recent evidence shows that older people want to interact with new technologies, where older adults' relationship with technology has traditionally been pessimistically portrayed. Together these studies provide important insights into the ergonomic issues of touchscreen devices. It can be concluded that the perception of elderly users not wanting to use smartphones can be disregarded.

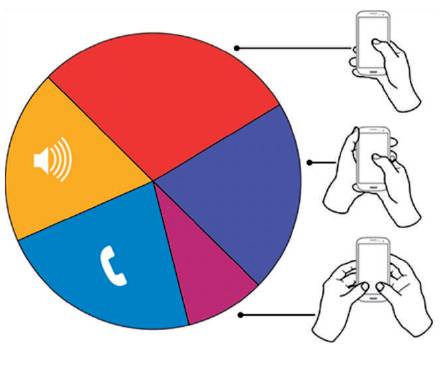

An interesting insight to pursue is how age effects how people use their phones. This provides an exciting opportunity to advance our knowledge of interaction styles. Investigating styles of interaction is of interest to understand how users interact with touchscreen devices. Several studies have documented three core styles of interaction. Hoober (2013) described three ways that users held their phones when touching the screens or buttons; one-handed; cradled and two-handed. Figure 3 demonstrates the results of his study with 49% adopting a one handed approach; 36% cradled, and 15% two handed.

Figure 3. Three Core Styles of Interaction (Hoober, 2013)

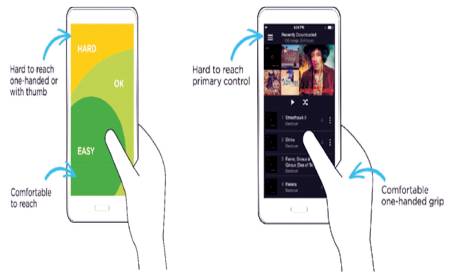

Wroblewski (2014) found that on large screens relying on your thumb and a one handed grip for touch screen use can stretch people's thumbs well past their comfort zone to reach controls at the top of the device, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Thumb Reach (Wroblewski, 2014)

Wroblewski (2014) supported Hoober's study as in his analysis of 1,333 observations of smartphones in use, he found about 75% of people rely on their thumb and 49% rely on a one-handed grip to get things done on their phones. There is an increasing concern that some interaction styles are being disadvantaged due to the recent trend of bigger screens. Hoober (2013) identified that the amount of the screen that is being obscured by positioning of a finger may explain the shifting of user's interaction style. He suggested that as designers, we should always be aware of the content that a person's fingers may obscure. Considering all of this evidence, it seems that using touchscreens create an instant compromise for users. Collectively, these studies highlight the need for consideration of the older generation with regards to touchscreen use. Jin, Plocher & Kiff (2007) investigated the optimum button size and spacing for use by older adults. The analysis was conducted as current recommendations were aimed at general audiences and fail to consider the specific needs of older adults confirming the need for further research into this area. Much uncertainty still exists about the relationship between interaction styles and age. Despite the influence of ergonomics, evidence demonstrates that ergonomic guidelines are not always adhered to with regards to touchscreen design. It would be beneficial to explore if this is noticed by end-users and reflected with opinions of their experiences. Of most interest is exploring the relationship between interaction styles and age. A gap in the literature review revealed a focus for further research looking specifically at the association between age and styles of interaction. There is a need to address whether touchscreen interfaces have been designed as inclusive for all.

Initially, qualitative research was undertaken to better understand user opinions around touchscreen practice and awareness of errors in use. Subjective measures were carried out via the use of communication with participants. Further quantitative research aimed to discover if the ergonomics of an older user is at a disadvantage when compared against that of a younger user. Objective measures were undertaken in an experiment to compare the style of interaction and reveal the ease of use and error count from the users. Given that the main aim of this study was to investigate if the ergonomics of older adults have been considered when designing touchscreen interfaces. The methodological objectives helped define the type of research that was needed to be undertaken.

Objective one required a collection of subjective information, leading to a qualitative research approach. Research methods considered here included surveys and questionnaires, interviews and focus groups. In weighing the advantages and disadvantages of these methods, the adopted approach leaned towards interviews or focus groups. This was due to the rich data that may be collated, alongside providing unique insights perhaps not thought of prior to the interviews/focus groups. The disadvantages of these methods namely time consumption and preparation, was overcome with prior planning. The use of a combination of focus groups and interviews for differing age groups provided the best way to avoid too much time consumption. Objective two involved the use of objective measures, requiring a quantitative method of experiments. The disadvantage of ethical issues can be overcome, whilst the experiment could also be planned to be as least time consuming as possible.

The first study addressed the investigation of objective one and was comprised of two stages, focus groups and interviews. Stage one of the study required the selection of seven participants in the 18 to 25 year old age - range for the focus group in order to provide a meaningful debate. Subsequent to this, interviews to obtain results from older users in the age range 60 to 70 years old. Garfein, & Herzog (1995) defined older adults in three categories; young-old age 60-69, old-old age 70-79, and oldest-old age 80 plus. The age of 60-70 was chosen to improve the likelihood of participants having some previous touchscreen experience. Interviewees with fifteen older users were undertaken to gather enough information to be meaningful.

Study 2 was aimed at addressing objective one and took the form of an experiment which investigated the interaction styles of younger and older users. The participants were selected from the focus group and interview stages, and were provided with information on what the experiment involves prior to the study. The study required the participant operating a touchscreen phone using a QWERTY keyboard to type the phrase 'The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog'. The results aimed to provide immediate error analysis and success rates, alongside the participants chosen interaction style. The results were compared to the results of study 1 to discover if the user's opinions on how they did were reflected by the results.

Initially, an interview with a user experience (UX) design expert was undertaken to establish a base-line and develop greater awareness of existing views. He highlighted that as we've grown up with menu based interactions we are accustomed to it. However, there is nothing particularly logical about it, “where if you can just touch something on the screen, once you've learnt that touching it opens it, then actually in more ways they are more accessible”. This provided a good base for further research and from these results of the main data collection it was possible to draw key findings.

There was a sense that older users tended to blame themselves for errors when typing, while younger users blamed the technology. For example, one older user who was interviewed stated: “I don't know what's going on here, I don't seem to be able to do it right”, in contrast to a younger user from the focus group who stated “oh I hate it when it does that”. The use of the term 'it' shifts the blame from the user onto the phone. These results suggest the older adults struggle to use technology, alongside the younger user's quick decision to blame it.

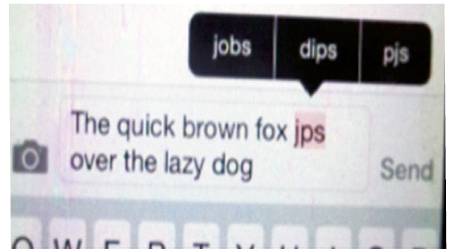

If we now turn to look at the errors in more detail, there was a noticeable relationship between the user's opinions on what they thought they did and what they actually did “do you ever experience any errors?”; “not really, um, it just comes up anyway, doesn't it, so”. Surprisingly, as shown in Figure 5, the majority of the participants made multiple errors, but often corrected them without thinking about it.

Figure 5. Errors during Task

Collecting background information about each user at the start revealed much about their use of technology in regard to touchscreens. When asked about the use of a QWERTY keyboard and predictive text the results gave conflicting opinions (Table 2). Four broad themes emerged from the analysis; brand, 'likers' and 'haters' of QWERTY keyboard use, touchscreen vs push button phone and positives and negatives of touchscreen use. These are supported by content in Tables 1-3 and Figure 11.

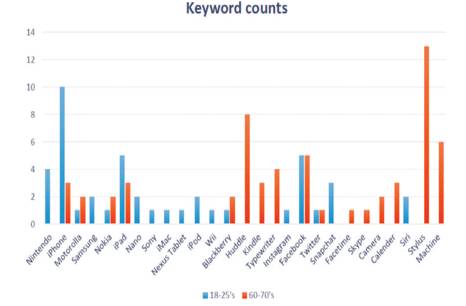

Supporting the common themes, it was possible to produce a keyword count to illustrate an overview of the most common brands and how they differentiate between younger and older users. As evident in Figure 6, the 18-25's recorded the most variety of different brand names. Interestingly the highest word counts were: Stylus - 13 (60-70's); iPhone - 10 (18-25's); Huddle - 8 (60-70's); Machine - 6 (60-70's); and Facebook - 5 (both).

Figure 6. Keyword Counts

In consideration of the largest theme throughout the research collection, the positive and negative points of touchscreen use which may be seen in Table 4.

Identifying the key themes from the qualitative data was nevertheless interesting but getting the users to undertake a task allowed the investigator to see if what the users described they did, correlated with the actions that they chose, as shown in Figure 7, demonstrating a participant's error. The style of interaction pursued by each participant was noted and allows for analysis against the qualitative data.

Figure 7. Task Example

The results of the first 7 participants show a unanimous twohanded approach by the younger generations as evident in Figures 8-14. A common choice of style for the older users was the cradle approach as shown in Figures 15-25.

Figure 8. P2 Two-handed Approach

Figure 9. P3 Two-handed Approach

Figure 10. P4 Two-handed Approach

Figure 11. P5 Two-handed Approach

Figure 12. P6 Two-handed Approach

Figure 13. P7 Two-handed Approach

Figure 14. P8 Two-handed Approach

Figure 15. P9 Cradle Approach

Figure 16. P9 One-handed Approach

Figure 17. P10 Cradle Approach

Figure 18. P10 Stylus Approach

Figure 19. P11 Cradle Approach

Figure 20. P11 No Hands

Figure 21. P11 Cradle Approach

Figure 22. P11 No Hands

Figure 23. P12 Cradle Approach

Figure 24. P12 Cradle Approach

Figure 25. P12 Cradle Approach

To better understand the results, the discussion allows the topic to be considered against the research questions. The themes identified in these responses show a contrast in opinion between the age groups, but also within the age groups, creating an opportunity for further discussion.

The first question in this study sought to determine how the interaction styles of older users differs to that of the younger users and whether their interaction needs have been considered when designing touchscreen interfaces. Study one set out with the aim of assessing the importance of user's opinions with regards to touchscreen use. The results of this study revealed four strong themes which were supported by qualitative data. The most obvious finding to emerge from the analysis is the differing relationship between older users and their association with brands, “what's that, a Nokia?”; “something like that yeah” (PH+10: older user I2, line 3), contrastingly to the younger users “iPhone”; “iPhone 5”; “iPhone 6”; “5C”; “iPhone 6”; “iPhone 5”(P2+3+4+5+6+8: FG, 3:21).

One unanticipated finding was that older users referred to calendars and cameras as apps, “Email, Google earth, Facebook, FaceTime I'll say because I use that sometimes, calendar, camera I have used” (P9: older user I1, line 20) whereas this was not classified as an app or mentioned once during the younger users focus group “Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat” (P4: FG, 5:21). This finding confirms the association between older users and being behind times with the latest technology. Furthermore, this is supported by a participant stating “I'm not interested in some of the more fast moving apps you've got there, I'm a dinosaur”. A possible explanation for this might be that the participants spoken to are not truly representative of the 60-70's age range. This study raises the possibility that older users are more concerned with function, than on brands, unlike the younger generation. These results are consistent with those of other studies and align with Hornor's (2014) account that argues the introduction of flat design excludes users as they are too confusing and not intuitive enough.

This study set out with the aim of assessing the style of interaction with a particular focus on the use of the QWERTY keyboard on a touchscreen phone. It is interesting to note that all 12 participants of this study had varying opinions on the use of the QWERTY keyboard, from 'liker's' to 'haters' throughout the age groups.

Contrary to expectations, this study did not find a significant difference between the 60-70's and the 18-25's with regards to QWERTY keyboard use as there were mixed opinions on the use, dependant on experience.

On the question of touchscreens vs push button phones, this study found that as a general correlation younger users swayed towards touchscreens and older users towards push button phones. One unanticipated finding was that there would be participant anomalies amongst both age groups. “I really like my buttons, I was really sad when I swapped it over, I'm used to it now but I preferred having buttons” (P7: FG, 21:54). This inconsistency may be due to experience. It may be that the more experienced participants benefited from positive experiences with touchscreens, whereas those with less experience swayed towards what they knew. “Touch screen because I'm used to it, habit”; “habit yeah” (P2+8: FG, 21:36) demonstrates the younger users swaying towards touchscreens, whereas the following statement demonstrates an older users opinion of push buttons “do you find it more logical to use a menu?”; “In a funny way I suppose because I've done this so long” (PH+9: older user I1, line 107).

These findings may help us to understand that the attitudes of all participants are based upon experience. This finding is in agreement with Burrows, et al. (2011) findings which showed that older people want to interact with new technologies. However, when combined with Langdon's, et al. (2014) opinion it becomes clear that as the education level has an impact upon learning, this may be the cause of older adults discomfort with new technology (p. 25).

The positives and negatives of touchscreen use provided the largest set of significant clusters of qualitative data. The most relevant of these are the size of the phone, the sensitivity of touch and the size of buttons. In the current study, comparing the positives against the negatives showed that negatives were more populated, with participants quick to criticise.

The size of phones were a point of complaint by the younger users “I can't reach the top corner, to click the cross to close pages, like on Facebook, I have to double tap and bring everything down so its within my span” (P5: FG, 17:00), where the older users swayed towards a more positive view: “presumably this would send a bigger message [iPhone with bigger screen than Motorola], than that will because on that there's only so many pages before it won't, you know, that's why I do quite abbreviated messages like 'u' 'r'” (P12: older user I4, line 127). A possible explanation for these results may be the lack of adequate equipment to enable a variety of different sized testing. It, may thus be suggested that younger users feel unsatisfied as they are continuously waiting for the latest innovation to arrive. Contrastingly, the older users appear to have a more positive outlook and seem impressed by new technology. This finding confirms the association between older people wanting to interact with new technologies (Burrows, et al. 2011).

The sensitivity of touch was a point raised by both age categories: “probably the sensitivity of the touchscreen as such, that once you get the lightness it's okay, but when you first start out you only have to touch it slightly heavier than usual and you get a double touch, or you can actually catch it on the sides and do the wrong thing” (P11: older user I3, line 128). This finding was not predicted and suggests that responsiveness is important in developing a successful touch screen device. There are similarities between the attitudes expressed by participant 11 in this study and those described by Pickering (1986) suggesting that touchscreens might still meet users' expectations, even if they have not been ideally designed (see pg 21).

A point discussed further by participant 11, ties into the third cluster of the size of buttons; “it's not obvious to me at the present time which buttons to push to get the machine to work, on a small screen like a phone, you have no space to show all the things you can do” (P11: older user I3, line 126). It is possible that the relationship between the screen size and button size may be the cause of the participant's issues. This finding has important implications for further development of interface design.

As mentioned in the literature review, brands have implications upon user's perceptions. The production of the keyword count graph seen earlier in Figure 6 demonstrates the younger generation's admiration for brands, and older user's preference for function. These relationships may partly be explained by knowledge and a desire to show brand loyalty and fit in. This can be supported by the finding “I think it's a Samsung S4 mini isn't it?”; “edgy”; “controversial” (participants 7+3+4: focus group, 3:45) demonstrating that the only participant out of the younger users to own a Samsung is seen as 'controversial'.

One interesting finding is the mention of the word 'machine' during the 60-70's interviews. The fact that the elderly still view a phone as a machine, is polar opposites to the view point of a younger user who sees it as the latest must have gadget. There is a great contrast between these attitudes and those expressed by Burrows, et al (2011). Interestingly, in this study, buttons were found to be necessary, even on a touchscreen device. “Would you prefer it without the physical buttons?”; “no”; “no I like the feeling” (participant H+ALL+5: focus group, 23:35). Participants of the focus group agreed that they would all still want physical buttons for the key functionality of a touchscreen phone.

Another important finding was that of the mention of the word 'stylus' as the most commonly spoken word, being said 13 times by the 60-70's. Further studies, which take this variable into account, may be beneficial in the future.

Contrary to expectations, this task found a significant difference between the user's opinion of what they do and their physical style of interaction and error count they encounter. The older user's physical style of interaction changed a lot. Varying between their own phones and a touchscreen, a common choice of style was the cradle approach. It was useful to notice other interaction styles that were not mentioned by Hoober (2013). What is interesting in this data is the use of stylus, alongside some participants using no hands; instead choosing to use furniture or knees to rest the phone on (see figures 23+25+27). Contrastingly, the younger users all opted for a two-handed approach, which could be explained by experience.

Supported by the photographic evidence shown in the results section, it is possible to notice that participants make multiple errors when typing. This is contrary to statements such as “how do you find using the keyboard, do you ever experience any errors?”; “not really, um, it just comes up anyway, doesn't it, so” (participant H+9: older user interview 1, line 35). It is difficult to explain this result, but it might be related to the pressure felt upon the participants to perform, perhaps causing them to speak highly of themselves in the qualitative data, yet feel more pressure to do well in the task, causing a skewed results. These results therefore need to be interpreted with caution.

Several limitations to this pilot study need to be acknowledged. The sample size is small, therefore not truly representative of the views of all users within the age categories. A limitation of using qualitative data is that it precludes reliability and can be questioned due to lack of standardisation. Results do not represent the whole population, so cannot be generalised. Being limited to one phone, this study lacks variety in being able to analyse and recommend the best relationship between age and touchscreen use. Improvements lie in bringing together a greater number of participants and a more structured experiment on multiple phones. The most important limitation lies in the fact that making participants use an unfamiliar phone and putting them in an unnatural situation may have created inaccurate results. The participants may have felt under pressure from the investigator to do well, again skewing results. A major limitation of this study is the participants being too aware of what they were doing that it wasn't a natural reflection.

In this investigation, the aim was to assess the physicality of touchscreen interfaces, and discover if they are designed to be inclusive and consider ergonomics with a particular focus on the use of the QWERTY keyboard. Returning to the question posed at the beginning of the study; have the interaction needs of older adults been considered when designing touchscreen interfaces and how do these differ to the younger generation? It is now possible to state that the interaction needs of older adults have been considered when designing touchscreen interfaces, but not as successfully as for the younger generation. The results of this investigation show that although age is a contributing factor, experience is really what differentiates the positive opinions from the negatives.

Taken together, these results suggest that interaction styles differentiate between age, with the younger users adopting a two handed approach using the thumbs to type and the older users taking a cradle approach, using one hand to support and one finger to type. This research will serve as a base for future studies and more in-depth research into the relationship between age, experience and preferred interaction styles. This paper has argued that although designers have considered the interaction needs of users when designing touchscreen interfaces, there is still room for improvement in certain areas. This study has found that more focus needs to be made on the interaction of the QWERTY keyboard, alongside the sensitivity and responsiveness of touchscreens. The study has gone some way towards enhancing our understanding of the attitudes surrounding inclusive design, the consideration of ergonomic issues and preferred styles of interaction in relation to touchscreen phones.

A future study investigating quantitative error count would be very interesting. The data would allow for a direct comparison of age in relation to touchscreen use and error count. Combining this with a qualitative method, such as an interview, would provide further evidence into the relationship between what participants think they do and their actions. If the debate is to be moved forward, a better understanding of interaction styles needs to be developed. With only 3 core styles of interaction introduced in the initial research, the task found participants using alternative ways of interacting, suggesting a need for a wider range of terminology to be developed.

It is recommended that further research be undertaken in the area of stylus use as this was a common point of reference for older users. Considerably more work will need to be done to determine how experience, rather than age, affects the use of a touchscreen. This would be a fruitful area for further work. A natural progression of this work is to move on from QWERTY keyboard use to analyse the ease of navigation for users through different app processes.

Considerations for further product design could involve using a layered approach to interface design, allowing the button size to increase and reducing error count. Greater efforts are needed to ensure easier navigation while maintaining inclusive design.