Table 1. Denny's Revenue and Locations, 2012

The case discusses Denny's Corporation, the largest full-service restaurant chain in the United States, and the evolution of its diversity management. During the early 1990s, Denny's was involved in a series of discrimination lawsuits involving cases of servers denying or providing inferior service to members of minority racial groups, especially African American customers. The restaurant chain acquired a reputation as a “poster child for racism.” At the time Denny's had no diversity training and almost no members of minority groups held management positions, owned franchises, or had vendor contracts. After a $54.4 million settlement for the discrimination lawsuits, Denny's rolled out an industry-leading racial sensitivity training program for all of its employees. In 2008, Denny's had come to be considered one of the nation's best companies in dealing with delicate racial issues. It appeared on lists of top places to work for minorities and women, an indication that it has completely reversed its direction on diversity. Rapid technological change, globalization, the demand for skills and education, an aging workforce, and greater ethnic diversification in the labor market had all contributed to making diversity management a high priority for Denny's and its rivals in the competitive U.S. restaurant industry. However, diversity also had negative effects on companies in the industry, and in spite of its commitment to diversity, performance at Denny's suffered. Hard evidence that managing diversity provided a discernable business advantage was elusive.

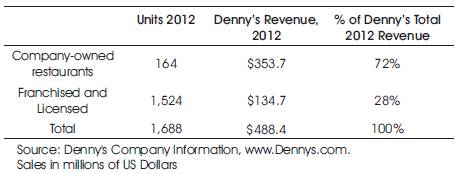

By 2013, Denny's had completed an intensive, almost two-decade long organizational transformation that brought it back from the brink of ruin. The change not only included addressing a problem of racial discrimination that had driven away customers and invited expensive lawsuits, but also a realignment of the franchise ownership structure. In 2012, Denny's Corporation was the leading full-service family-style restaurant chain in the U.S. The Company generated $488.4 million revenue in 2012, and owned and operated 164 of its 1,688 locations at the end of 2012; the rest were franchised or operated under licensing agreements (see Table 1).

Table 1. Denny's Revenue and Locations, 2012

In 1994, Denny's had paid more than $50 million to settle two class-action lawsuits filed by African-American customers claiming that Denny's restaurants refused to serve them. When Denny's was hit with a series of classaction discrimination lawsuits in the early 1990s, it had no diversity training and almost no minorities held management positions, owned franchises, or were significant vendors. Denny's struggled from 1994 to 2008 to recapture sales from minority customers, and came to be a powerful example to other American companies of the importance of managing workplace diversity.

After instituting Company-wide training, policies, and safeguards in the area of discrimination, and making efforts to hire more minorities across all ranks, Denny's came to be considered as one of the nation's best companies at dealing with delicate racial issues. It appeared on lists of top places to work for minorities and women, an indication that it has completely reversed its direction on diversity (Richardson 2006). Denny's management remained convinced that the diversity of its employees and customers would translate into increasing revenue and greater profits. Yet, in spite of the Company's commitment to diversity, performance at Denny's suffered; year-to-year sales declined at an average of 12% from 2007 to 2012.

Denny's was one of the most widely recognized names in family dining in the U.S., providing good food and service for more than 50 years. It operated restaurants in the United States, Canada, Curacao, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, and Puerto Rico. Denny's restaurants offered a casual dining atmosphere and moderately priced meals served 24 hours a day at most locations. Denny's was well-known for its breakfasts served around the clock, including the popular Meat Lover's Breakfast and Original Grand Slam. Denny's menu also featured a variety of appetizers, hamburgers, sandwiches, salads, chicken, steak and seafood entrees as well as desserts.

In 2012, the Company owned and operated 164 restaurants, and another 1,524 were franchised or operated under licensing agreements. There were 8,000 employees at Denny's Company-owned restaurants. Denny's ended 2011 with sales of $538.5 million. The Company was publicly traded on NASDAQ (National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations), under the ticker DENN.

Denny's was founded under the name Danny's Donuts in 1953 by Harold Butler in Lakewood, California and initially served only donuts. One year later, the menu was expanded to include sandwiches and other food, and the store was renamed Danny's Coffee Shops. By 1959, there were 20 restaurants in operations, and the chain was renamed Denny's restaurants. By 1963, expansion through franchising resulted in a total of 78 coffee shops operating in 7 states. In 1966, Denny's made its initial public offering on the American and Pacific Coast Stock Exchanges; the additional capital and continued operational success allowed it to grow to over 1,000 restaurants by 1981. In 1987, Denny's was purchased by TW Services, Inc., one of the largest restaurant companies in the United States. TW Services changed its name to Flagstar Corporation in 1993. Between 1993 and 1997, Flagstar was in turmoil. The first racial discrimination lawsuits were filed against Denny's and Denny's diversity management program eventually followed. In 1996, Denny's CEO Jim Adamson (Figure 1) was named “CEO of the Year” by NAACP (National Association for the advancement of Colored People), but one year later Flagstar (Denny's parent company) filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection from creditors. The company reemerged in 1998 with a new name, Advantica Restaurant Group, Inc., only to change its name once again to Denny's Corporation in 2002.

Figure 1. Former CEO Jim Adamson

In both 2000 and 2001, Fortune magazine ranked Advantica/Denny's No. 1 in its list of “America's 50 Best Companies for Minorities.” In 2006, Black Enterprise magazine included Denny's in its list of the “Best 40 Companies for Diversity.”

In 2012, Denny's ended its fiscal year with sales of $488,363 million and net income before taxes of $35,094 million. This contrasted sharply with its income before taxes of negative $6.1 million in 2005 (Denny's 2008) .

Denny's brand had always been built on full service, 24 hours a day. Denny's restaurants generally were open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The “always open” operating platform provided a distinct competitive advantage.

Denny's growth strategy was built upon providing quality menu offerings and generous portions at reasonable prices with friendly and efficient service in a pleasant atmosphere. Sales were broadly distributed across each part of the day (breakfast, lunch, dinner, and late-night); however, breakfast items accounted for majority of the sales.

Denny's vision was to recognize that each customer had certain reasonable expectations that must always be met. These included quality food that tastes good; friendly, attentive servers who make customers feel welcome; clean, well-maintained surroundings; and prices that represented good value (Denny's, Company Information 2008) . Denny's vision was summed up in the proprietary slogan, “Great Food, Great Service, Great SM People ... Every Time! ”

The restaurant industry was divided into three main segments: full-ser vice restaurants, quick-ser vice restaurants, and other varied establishments. Full-service restaurants included the mid-scale, casual dining and upscale (fine dining) segments. A large portion of midscale business was generated in three categories: familystyle, family steak, and cafeteria. The casual dining segment was characterized by complete meals, menu variety and moderate prices. The family-style category, which included Denny's, consisted of a small number of national chains, many local and regional chains, and thousands of independent operators. The casual dining segment, which typically had higher menu prices and generally offered alcoholic beverages, included a small number of national chains, regional chains and independent operators. The quick-service segment was characterized by lower average checks, portable meals, fast service and convenience.

Overall restaurant sales had been rising just over 5% annually, however, the supply of workers, aged 16 to 24, the primary pool for restaurant employees, had been declining. To solve the problem, companies were hiring more retirees and immigrants, and were increasingly making use of automation. A slowing economy helped offset a shrinking labor force by keeping wages (often minimum) stable, thus posing less threat to profits.

The restaurant industry was mature and rivalry among chains was intense. Restaurants had to deal with stiff competition, fickle customers, and low profit margins. Companies continue to grow through acquisition rather than through building new units, which cost upwards of $1 million even for a fast-food unit. In 2007, the industry had started to showcase additional sub-categories, including quick-casual and home-meal replacement, which were two of the fastest growing segments within the food service industry. According to the National Restaurant Association, the industry sold $533 billion in 2008 and by 2012, the nation's 998,000 restaurants would achieve over $660 billion in sales, or 4 percent of the U.S. GDP (Gross Domestic Product). The quick-casual segment alone would experience double-digit percentage increases.

According to the Quantified Marketing Group, although the quick-casual restaurant sector was still in its infancy, this segment would continue to dominate industry growth by dividing into even smaller and more specialized categories. Cereality and Peanut Butter & Co. were two examples of successful one-product concepts that emerged. Cereality was founded in 2003, served only cereal, and allowed guests to create customized cereal combinations with a number of toppings and choices of milk. Peanut Butter & Co. was a sandwich shop, started near New York University, that offered a menu made up entirely of signature peanut butter sandwiches. By 2005, the company had begun to expand nationally. Mature brands would have to reinvent themselves to stay competitive, and some national chains would be forced to reposition themselves in the face of new industry developments (Quantified Marketing Group 2007).

The restaurant industry was highly competitive, and competition among major companies that owned or operated restaurant chains was especially intense. Restaurants competed on the basis of name recognition and advertising; the price, quality, variety, and perceived value of their food offerings; the quality of their customer service; and the convenience and attractiveness of their facilities. Competition for qualified restaurant-level personnel remained high.

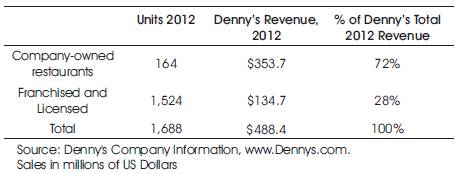

Denny's domestic competitors in the family-style segment included a collection of national and regional chains. Denny's national competitors in the casual dining segment were IHOP (International House of Pancakes) and Waffle House, wherein Denny's ranked first, IHOP second and Waffle House third. IHOP had 1,535 (mostly franchised) restaurants, typically open 24-hours per day. In 2007, DineEquity, Inc. was formed from IHOP, and acquired Applebee's, one of the nation's largest dinner house chains with 1,970 restaurants. Waffle House was a privately owned chain of more than 1,500 restaurants; typically open 24 hours per day. Denny's also competed with dinner house companies (such as Applebee's, and the restaurant brands owned by Darden, Brinker, and OSI Partners), and with quick service restaurants such as McDonalds. By the mid-2000s, the quick service restaurants had upgraded their menus with entree salads, full breakfasts, and other such items in an attempt to capture sales from the casual dining segment. Denny's competitive strengths included strong brand name recognition, well-located restaurants, and significant market penetration. The Company benefited from economies of scale in many areas such as advertising, purchasing, and distribution. Denny's compared with rivals and industrial averages are shown in Table 2 and 3 respectively.

Table 3. Denny's Compared with Industry Average

During the 1990s, Denny's was involved in a series of discrimination lawsuits involving several cases of servers denying or providing inferior service to members of minority racial groups. There were three notable incidents.

Countless other incidents similar in nature occurred throughout the Denny's chain. After the six officers filed a lawsuit for discrimination based on race, thousands of other customers reported that they had experienced similar discriminatory incidents at Denny's Restaurants nationwide (Labaton1994). Eventually, the lawsuit involved class members in 49 states. The U.S. Justice Department investigated what would become the largest such case at the time under the public accommodations section of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Denny's reputation plummeted. News papers, magazines, radio talk shows and television shows repeated and retold the discrimination incidents at Denny's. Cartoons appeared in newspapers making fun of the chain. Television comedians Arsenio Hall, Jay Leno, and others poked fun at the restaurant chain. In his monologue on The Tonight Show in May 1993, Leno quipped: “Denny's is offering a new sandwich called the 'Discriminator.' It's a hamburger, and you order it, then they don't serve it to you” (Kohn 1994).

The original reaction by Denny's top management was that the discrimination cases were isolated incidents. But sworn statements by employees described instances of Denny's managers teaching restaurant operators how to discourage black customers, and some former restaurant managers told of a policy, that required certain customers (which the managers understood to mean black customers) to pay cover charges and for meals in advance of being served. Top management was determined to contest the lawsuits, even as the evidence of wrongdoing piled up nationwide. To get Denny's out of the headlines, Flagstar, the company that owned the Denny's chain, signed a pact in 1993 with the NAACP pledging to hire minorities and increase purchases from minority owned businesses. The NAACP and Flagstar also agreed to participate in a jointly administered program to ensure that Denny's customers were treated fairly. According to the lawyers and plaintiffs involved in the class-action suits against Denny's, the NAACP agreement may have been a step in the right direction, but it did nothing to address the past discrimination.

Eventually, the Company conceded defeat and settled the class-action lawsuits. By December 1995, Denny's had paid out $54 million to some 295,000 customers and their lawyers (Labaton 1994). In addition, Denny's signed a consent decree, which placed the corporation under an extensive court order to provide nondiscrimination training to its employees and to monitor and report future instances of discrimination.

In 1993, the year of the worst racial incidents, Denny's sales declined considerably. Operating income declined 30 percent from the previous year. The lawsuits also affected the Company's public perception. A 1997 study indicated that nearly 50% of African Americans associated the restaurant chain's name with racial discrimination.

Workplace diversity referred broadly to the protection, respect and inclusion of the entire package of attributes that each employee contributed to the workplace. While companies initially paid the most attention to those characteristics that were protected by federal and state equal employment opportunity laws (such as race, sex, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, age, and disability); businesses were increasingly seeking to build company cultures that respected life experiences, languages, talents, skills, thought processes, and personal styles. Different skills, experiences and backgrounds in the workplace, it was thought, could foster business growth, innovation and success.

While companies retained the internal focus on attracting and retaining a diverse workforce and fostering a culture of inclusion, they were also adding an external focus that recognized the diversity of their customers and vendors and the communities in which they operated. In 2008, many companies were developing far-reaching strategies that relied on the input and expertise of diverse workforces to compete in increasingly global and varied markets. Furthermore, they were recognizing that a global diversity commitment might translate into unique programs, products and services in different parts of the world. The trend was to intensify, as global commerce continued to bring different cultures, values and practices into contact with one another.

The real work of turning around Denny's began when CEO Jerry Richardson stepped down in 1995. It was reported that Richardson wanted to devote more of his time to his football team, the Carolina Panthers. Richardson was replaced by Jim Adamson, who let all employees know from the beginning that he wanted to provide better jobs for minorities and women. Adamson devised a four-part strategy for Denny's cultural construction:

In 1995, Adamson hired Rachelle Hood-Phillips as Chief Diversity Officer to help turn the Company around. She was the nation's first diversity manager to report directly to a CEO. When Hood-Phillips joined Denny's, her priority was to interface with 70,000 demoralized workers who had largely been considered guilty of racism by association (Adamson 2000).

Under Hood-Phillips's direction, the Company would spend millions on diversity initiatives that brought legions of new minority managers, franchisees and suppliers into a Company formerly run almost exclusively by White males. In 1994, before Hood-Phillips hiring, there were no franchises owned by an African-Americans. From 1995 to 2000, Denny's redirected 14 percent to 15 percent of its marketing budget to campaigns aimed at minority customers. The Company spent as much as $14 million in one year on the effort.

The Company's first goal was to get rid of employees at all levels who failed to embrace its diversity initiative. Next, Hood-Phillips developed a system that evaluated and reported the initiative's progress quarterly. The CEO and board of directors, as well as representatives of the NAACP, were involved in monitoring the system.

Hood-Phillips continued to focus on serving as the Company's point person in an ongoing quest. She instituted mandatory diversity-training sessions for every worker at every level of the Company, from cooks and cashiers to the Chief Executive Officer. From the ground up, Hood-Phillips built the materials and structure that made the turn-around of Denny's image possible. Hood- Phillips developed initiatives to monitor progress in every area of Denny's operations, paying close attention to strategic decisions and actions of senior management and board members that affected everything from purchasing to philanthropy. Denny's had no minority suppliers or contractors in 1995. Hood-Phillips pushed its buyers to dole out business to minority-owned companies and hunted up contacts to help advance the effort. As a result, between 1995 and 2000, Denny's spent $616 million with minority suppliers.

Denny's had never directed charitable contributions to minority-related organizations. That changed in 1995, when the Company gave $1.3 million to civil and humanrights causes. And recruitment of college graduates, which had been aimed largely at top national business schools, was revised to include smaller, less well-known schools that more minorities attended, particularly historically Black colleges. In 2003, Denny's led a campaign to raise funds for its “Re-ignite the dream campaign” aimed at promoting Martin Luther King's legacy (Mehegan 2003). Denny's reserved 20 cents from the sale of every All-American Grand Glam breakfast, and in 2004, Ray Hood-Phillips (Figure 2) proudly handed a check for $1.2 million to Coretta Scott King, widow of the civil rights leader, for the King Center in Atlanta (Adamson 2002).

Figure 2. Ray Hood-Phillips

Former CEO Jim Adamson, wrote: "If there was one person who had led the way in moving [Denny's] toward an inclusive workplace, it would have to be Ray Hood- Phillips.”

Nicknamed 'Ray', Hood-Phillips grew up in the central city of Detroit and graduated from Michigan State University, where she earned her Master of Arts degree in communication, arts and science. Hood-Phillips worked to build a long and successful track record in advertising and marketing at major agencies in the Midwest.

Hood-Phillips had been responsible for diversity at Burger King Corp, when Adamson was president there. At Burger King, she broke the glass ceiling and became the highest ranking Black woman in the Burger King Corporation, earning the title of vice-president of human resources.

She later was asked to start a new department: Minority Affairs. To some degree, the new department was a response to earlier charges of discrimination made by minority franchisees and suppliers against Burger King in the early 1980s. Hood-Phillips created an innovative program at Burger King that Adamson described as "incredible." Her tough, yet compassionate diversity training program allowed employees to communicate what they were feeling about race and ethnicity in the workplace. Participants signed confidentiality statements to ensure that what was said in the group would not be disclosed to outsiders. In this way, group members felt safe enough to share their deepest fears, and their very real prejudices. The training took place in three-day sessions for groups of 20 to 25 people at a time. Hood-Phillips intended the program to do more than just get people to vent. The program showed people how to overcome the narrow-mindedness it exposed, and to build, in Hood- Phillips's words, “productive, collaborative partnerships across lines of difference.”

When Hood-Phillips followed Adamson to Denny's, she proceeded to give the Company an attitude overhaul. "We had to look at every system especially how you hire, fire, promote and develop people and eliminate anything that would impede inclusion, and build back structures that would foster diversity. It's a huge job," she said.

The approach Hood-Phillips used was unusual. Instead of working through a human resources department, as would have been typical for most diversity officials, she operated from a position of authority equal to that of division heads. She used that authority to coax and push diversity initiatives throughout the organization. Other companies had diversity training similar to Denny's, but few achieved widespread participation. The result of her efforts was that Denny's went from diversity laggard to leader. Other companies took notice (Thorne 2002) .

One of Hood-Phillip's most important contributions was establishing a set of diversity metrics at Denny's. The Company began to measure systematically its performance on a number of diversity indicators. Each of Denny's 85,000 employees received an hour and a half of diversity training. The managers received nine and a half hours. Trainings ranged from a quick session for line workers that taught the basics of equality and respect for heritage to two-day courses for store managers that included details about diversity in hiring and the basics of anti-discrimination law. More than two million people took Denny's diversity training, according to a Company estimate. The Company claimed to be the largest diversity trainer in the U.S. In addition, performance appraisals for senior managers were based on valuing diversity. For those who refused to attend training, the CEO would withhold up to 25% of their bonuses (Kangas 2006) .

In 2008, only 10% of African Americans associated Denny's name with discrimination. Hood-Phillips remarked: “When we started tracking in 1996, nearly half of all African Americans had a negative image of Denny's, and associated it with discrimination.”

By 2004, women and minorities came to make up half of Denny's eight-member board of directors, and 45 percent of the 11-member senior management team. Members of minority groups owned 45 percent of Denny's franchised restaurants. In 1998, Fortune magazine ranked Advantica, Denny's parent company, as the second best company for minorities in the nation. In 2001, it climbed to number one. From 2002 to 2007, the Company consistently remained at or near the top of the Fortune Best Company for Minorities list (Faircloth 1998) . Ray Hood-Phillips concluded, “Diversity had absolutely been institutionalized at Denny's. Everybody owns this at Denny's.” However, by 2012, the Company had fallen off the Fortune list while industry rival Darden Restaurants had made the list. As of 2010, minorities made up 62% of the Denny's total workforce and 41% of overall management.

During the discrimination lawsuits and after, that financial problems proved difficult to overcome. In 1995, Flagstar (Denny's parent company at the time) lost $55 million on revenues of $2.6 billion. Struggling with a poor image and with annual interest payments of $230 million, the Company had lost Wall Street's confidence; the stock price plummeted. Flagstar sold 45 Company-owned restaurants to franchisees, resulting in Denny's revenues dropping from $1.55 billion in 1994 to $1.49 billion in 1995.

Adamson tackled the Company's problems on several fronts. To offset competition at Denny's, from fast food restaurants, he lowered prices, introducing five morning meals under $2 to supplement the chain's popular $1.99 Grand Slam breakfast. In addition, Denny's added a "value" lunch menu, with meals from $2.99 to $4.99.

In May 1996, Flagstar acquired two family dining chains, Coco's and Carrows, hoping to add more consistent performers to its stable of restaurant chains. Unable to continue under its staggering burden of debt, however, Flagstar spent 1997 reorganizing under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Flagstar finished 1997 with revenues of $2.61 billion, a slight increase over 1996, but reported yet another net loss, this time of $134.5 million.

In January 1998, Flagstar emerged from Chapter 11 with a new name, Advantica Restaurant Group, and a debt load $1.1 billion lighter. Adamson remained CEO, but the Company had a new board of directors and newly issued common stock trading over NASDAQ. Not only was Advantica in a more hopeful financial position in mid- 1998, it was receiving recognition for its dramatic turnaround in race relations. With a rejuvenated balance sheet and image, Advantica hoped to complete a solid turnaround.

In 2001, Nelson Marchioli, former President of El Pollo Loco restaurants, was asked to replace retiring Jim Adamson as CEO. Marchioli's task was to focus on firm profitability. Marchioli was a strong proponent of diversity, yet he claimed that he had never been able to quantify the financial benefits from the millions of dollars and years of effort invested in it. An effective diversity effort could prevent costly discrimination lawsuits, might help a company understand and reach its market, and could improve a company's image. However, “Diversity can't substitute for basic business execution,” Marchioli said (Speizer 2004).

Marchioli pointed out that when the discrimination complaints against the Company first surfaced in the early 1990s, Denny's weekly customer count was about 5,500 per store. In 2004, it was 1,000 to 1,200 fewer. "As we were making these incredible strides in diversity, guess who was still having a declining guest count?" Marchioli remarked that Denny's would continue to invest in diversity because "it is the right thing to do," and because it helped the Company understand and serve its diverse national customer base, which made it easier for the Company to attract customers. But Denny's had to do a better job of executing its business strategy in order to succeed.

There was conflicting evidence about the link between diversity and company’s performance. Diversity was a recognizable source of creativity and innovation that could provide a basis for competitive advantage. On the other hand, diversity was also a cause of misunderstanding, suspicion, and conflict in the workplace that could result in absenteeism, poor quality, low morale, and loss of competitiveness. Therefore, firms faced a tough challenge. If they embraced diversity, they risked workplace conflict, and if they avoided diversity, they risked losing competitiveness and spoiling their reputations with customers and the general public.

Diversity Research Network, a group of scholars drawn from six universities, examined four Fortune 500 companies in depth. They found that a variety of contextual variables, including an organization's culture, strategy, and human resource practices, helped to determine whether diversity boosted performance or dragged it down. The results of the study showed that when it came to team output, diversity could cut both ways. Moreover, simply matching a company's workforce to its market was unlikely to increase its odds of success. After analyzing data from a national retail chain, the Network found no evidence that most customers cared whether or not they were served by people of the same gender or race.

Employing workers of many different races also appeared to have little effect on average employee turnover in a retail workplace, although employees did quit more often if fewer colleagues were of their same race, according to a study by two professors at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkley. "The most important takeaway is that diversity itself doesn't matter much in terms of turnover for most groups of workers," concluded Leonard, who chaired the Haas Economic Analysis and Policy Group. "It suggests that people are, at least in this sector, pretty tolerant." The Haas findings contradicted an argument of some diversity consultants, who claimed that having a workforce that was both gender and racially diverse reduced turnover. The study also failed to find support for another line of thinking that argued that diverse workplaces experienced more friction and thus required special training (Kelly 2006).

From 2006 to 2012, Denny's sales declined from $994 to $488.4 million, and income before taxes tumbled from $44.8 to $35.1 million. Unit sales per Denny's-operated stores were $1.94 million per store. Denny's had recovered from the scandals and lawsuits of the early 1990s and had significantly improved its reputation as a place to eat and a place to work, but it continued to struggle to grow profitably.

In September 2006, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a lawsuit accusing Denny's for violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The EEOC claimed that Denny's had failed to provide reasonable accommodation to its workers with disabilities. Specifically, the EEOC alleged that Denny's refused to provide one of its Baltimore restaurant managers with reasonable accommodations for her disability, a leg amputation. The manager desired to return to work after an accident, only to find that Denny's would not allow her to work in the restaurant because of her disability, despite her desire to return to work, and fired her.

Moreover, the EEOC alleged that Denny's medical-leave policy violated the ADA, since Denny's policy automatically denied additional medical leave beyond a pre-determined limit – thus denying a possible reasonable accommodation for a disabled employee. Denny's denied all allegations. The EEOC asked the court to bar Denny's from applying its maximum medical leave policy to disabled employees, and on behalf of the Baltimore employee, sought lost wages and benefits, compensatory and punitive damages, and other relief. In what some might consider reminiscent of its original attitudes regarding the racial discrimination charges of the early 1990s, Denny's denied the allegations.

In June 2011, Denny's agreed to pay $1.3 million and furnish other relief to settle the EEOC case. In addition to providing compensation to the fired Baltimore manager, Denny's agreed to provide monetary relief to 33 additional workers who claimed they were denied reasonable accommodations and unlawfully terminated. According to the EEOC press release, “…the consent decree settling the suit also requires that corporate-operated Denny's restaurants reinstate certain identified workers, provide additional medical leave to reasonably accommodate disabled employees, provide anti-discrimination training and notice posting, with emphasis on the ADA and disability discrimination; a corporate-level oversight and review process for leave decisions; and reporting to the EEOC (U.S. Equal Opportunity Commission Press Release 2011) . The federal court will retain jurisdiction and EEOC will monitor compliance with the decree.” (Eeoc.gov 2012)

Denny's faced additional controversy, albeit on a much smaller scale than the discrimination charges, in the fall of 2012. Franchisee John Metz, owner of more than 30 Denny's restaurants, created controversy when he announced that all of his restaurants would be adding a five percent surcharge to customer's bills to cover the costs that he would incur under the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare as it is popularly known. Metz stated that customers could reduce the amount of tip they would normally give to the server to counter balance the surcharge if they wished. The reaction to Metz's statements were swift and harsh, with Denny's franchisees having to deal with angry customers, declining sales, and calls for boycotts.

Denny's chief executive John Miller immediately began damage control, writing, "We recognize his right to speak on issues, but register our disappointment that his comments have been interpreted as the company's position.” (Chun 2012) He also expressed his disappointment to Metz about the statements. Metz, for his part, backed down on the threat of the surcharge and released a statement that his previous statements were not representative of the Denny's brand or other franchises. (Chun 2012).

The demographics of America were rapidly changing, and managing a diverse workforce had become a critical matter for firms like Denny's. Denny's restaurant chain had transformed itself from a “poster child for discrimination” to a firm recognized for its leadership in workplace diversity. Denny's diversity turnaround served as an example of how fast and how far a company could progress – given enough motivation to do so, an aggressive strategy, and committed leaders. But had the Company really left its discriminatory history behind? Moreover, had Denny's programs to increase diversity over a 15-year period been “worth it” in terms of the Company's business results? Had the payoff from all the efforts and costs of managing diversity been big enough?

Denny's executives in 2013 and Denny's Menu card are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively. Denny's locations for the years 2006-2011 are shown in Table 4. Also, Denny's income statements, balance sheets and statements of cash flow for the years 2007-2012 are shown in Table 5, Table6 and Table 7 respectively.

Figure 3. Denny's Executives in 2013

Authors

Affiliation

Draft 12 March 2013

The case discusses Denny's Corporation, the largest fullservice restaurant chain in the United States, and the evolution of its diversity management. During the early 1990s, Denny's was involved in a series of discrimination lawsuits involving cases of servers denying or providing inferior service to members of minority racial groups, especially African American customers. The restaurant chain acquired a reputation as a “poster child for racism.” Comedian Jay Leno joked that Denny's offered a sandwich called the “Discriminator: you order it, then they don't serve to you.” At the time, Denny's had no diversity training and almost no members of minority groups held management positions, owned franchises, or had vendor contracts. After a $54.4 million settlement for the discrimination lawsuits, Denny's rolled out an industryleading racial sensitivity training program for all of its employees. In 2008, Denny's had come to be considered one of the nation's best companies in dealing with delicate racial issues. It appeared on lists of top places to work for minorities and women, an indication that it has completely reversed its direction on diversity. Rapid technological change, globalization, the demand for skills and education, an aging workforce, and greater ethnic diversification in the labor market had all contributed to making diversity management, a high priority for Denny's and its rivals in the competitive U.S. restaurant industry. However, diversity also had negative effects on companies in the industry, and in spite of its commitment to diversity, performance at Denny's suffered. Hard evidence that managing diversity provided a discernable business advantage was elusive.

The Denny's case is appropriate for undergraduate or graduate courses in Business and Society, Business Ethics, or Human Resource Management that explore discrimination in the workplace, the difficulties of implementing management practices to increase diversity, the challenge of changing an organization to embrace it, and the costs and benefits of a diverse workforce. In particular, the case provides a format for the examination of the question, “Does workforce diversity really enhance firm performance?”

The Learning objectives include:

The 1993 Amended Consent Decree by the U.S. District Court for Northern California describes the incidents of racial discrimination at Denny's, and is available full text online at

http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/housing/documents/dennysettl e2.htm

The following short and student-friendly article briefly reviews diversity management practices at Nordstrom, Denny's, and Xerox:

“Three Companies Show Why They Are Best-in-Class for Diversity” (2006, March 16). Knowledge@Wharton, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=1407

Wong (2006) provides a rather long (and somewhat repetitive) list of “best practices” in a 3-page article that may serve as a starting point for a discussion about what practices firms should follow:

Wong, H. (1999, April 15). “Best Practices in Diversity Strategies and Initiatives,” presentation at the Coast Guard Diversity Summit, available from http://152. 121.2.2/hq/g-w/Diversity/summit/speech2.htm

Several important studies have revealed that the relationship between diversity and organizational performance is complex and elusive. Recommended scholarly articles include Katlev et al.'s (2006) Assessment of the effectiveness of diversity policies, and Kochan et al.'s (2003) examination of the effect of diversity on performance:

Kalev, Alexandra, Erin Kelly & Frank Dobbin (2006). “Best Practices or Best Guesses? Assessing the Efficacy of Corporate Affirmative Action and Diversity Policies,” American Sociological Review, 71: 589-617.

Kochan, T.; K. Bezrukova, R. Ely, S. Jackson, A. Joshi, K. Jehn, J. Leonard, D. Levine & D. Thomas (2003). The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the Diversity Research Network, Human Resource Management, 42: 3-21.

Kwak provides a 2-page, practitioner-friendly summary of research findings that may constitute appropriate precase reading for students:

Kwak, M. (2003).The Paradoxical Effects of Diversity, MIT Sloan Management Review, 44 (3) 7-8.

Several sources are available to instructors that provide frameworks for managing change. The chapter below provides a framework for the content of change, a summary of the literature on the process of change, and briefly addresses change agents and change leaders. While written for nonprofit organizations, it can also be applied to a for-profit company:

McGuire, Stephen J.J. (2008). “Managing Change in Nonprofit Organizations,” Ch.7 in K.P. Kretman (Ed.), Nonprofit Excellence. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

A compelling framework for the analysis of types of organizational change and the process of managing strategic change can be found in:

Nadler, David A. & Michael L. Tushman (1989). “Organizational Frame Bending: Principles for Managing Reorientation,” Academy of Management Executive, 3 (3): 194-204.

The case was prepared based entirely on publicly available information. No author has any affiliation with Denny's.

The authors acknowledge research contributions by Hanna Tameru and James Brumfield, and suggested answers to discussion questions by Motaz Abutarboosh, Victor Voisard, and Taran O'Neil, graduate business students at California State University, Los Angeles.

The case has been class tested in undergraduate and graduate courses in Human Resources Management, and a graduate course in Business Ethics.

Wong (1999) defined diversity as “all the various characteristics that make one individual either the same or different from another…The overriding principle is that of inclusion and involvement 'no one stands outside of diversity'." Jones (2205), suggests that diversity encompassed arange of differences in ethnicity/nationality, gender, function, ability, language, religion, lifestyle or tenure with the organization. Additionally, diversity in the workplace includes more than employees' diverse demographic backgrounds, and takes in differences in culture and intellectual capability.

Diversity management refers to the systematic and planned commitment on the part of organizations to recruit and retain employees with diverse backgrounds and abilities (Jones, 2005). There are workplace, marketshare, and compliance objectives to diversity management. The workplace objective may be simply a function of local labor market realities, or it may center on the ability to attract and retain female and minority candidates who will bring fresh viewpoints to work. Marketshare objectives target the growing purchasing power of female and minority consumer groups, which many companies believe can be tapped only through an employee population that matches the customer base. Compliance objectives stress the need to avoid costly discrimination lawsuits and the damage to reputation that occurs when companies are charged with illegal workplace practices.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Section 703)] states, It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer,

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits employers from discriminating against qualified applicants or employees with disabilities. Employers with 15 or more employees are covered. The Act protects qualified individuals with disabilities from discrimination in all aspects of the employment process, including recruitment, hiring, rates of pay, upgrading, and selection for training. The Act also requires a covered employer to reasonably accommodate a qualified individual with a disability, unless it can show that, by doing so it would suffer an undue hardship. There are strategies for handling the reasonable accommodation of an applicant or employee and suggestions for evacuating an employee with a disability during a crisis. The ADA also protects applicants and employees from discrimination based on their association with people with disabilities.

The purported benefits of diversity include creativity, problem-solving, and productivity. Diversity, combined with an understanding of individual strengths and weaknesses, and working relationships that are founded upon sensitivity and trust, have been shown to enhance creativity and problem-solving capability. However, diversity can also damage cohesiveness. Some studies have shown that heterogeneous groups experience more conflict, higher turnover, less social integration, and more problems with communication.

It has been claimed that diversity programs yield higher performance and greater productivity, but the evidence offered is largely anecdotal or based on limited data collected through questionable methods. Despite the mounting anecdotal evidence from organizations that taking action on managing diversity makes an important contribution to business performance, there remains ongoing debate as to whether there is any discernible business benefit. Thomas A. Kochan of MIT wrote, "The diversity industry is built on sand; the business case rhetoric for diversity is simply naive and overdone. There are no strong positive or negative effects of gender or racial diversity on business performance.”

Kochan based his conclusions on a five-year study of the impact of diversity on business results. The study involved a detailed examination of large firms with well deserved reputations for their long-standing commitment to building a diverse workforce and managing diversity effectively. It is built on a growing body of research that raises painful questions for companies that pour money into diversity programs, and for the diversity industry that supplies them with a dazzling array of diversity products. Kochan found little evidence to support the business case for diversity, and conflicting, inconclusive evidence about the link between diversity and employee turnover (Kochan 2003) , (Richard 2002).

The combination of demographic trends, legislative pressure, and market forces- in regards to competition for scarce skills- make the need to manage diversity unavoidable for companies. Is it possible that there is a clear business advantage to workplace diversity, but it is more of a long-term investment and so it is hard to demonstrate measurable impact on financial success in the short-term? Diversity has become an inescapable social fact, so how can an organization maximize its benefits while minimizing its negative effects? How can an organization accurately evaluate and measure diversity management results and organizational impact?

The following is an adaptation of a presentation by Herbert Wong at the Coast Guard Diversity Summit (1999, April 15), in which Wong identified several best practices for diversity management:

Diversity initiatives need to be well defined and aligned with the organization's strategy, goals, and HR practices. Diversity and strategic goals are well understood by the members of the organization, and incorporated in reward and other HR practices.

“The organization develops a culture of inclusion and fairness, and communicates and implements organizational values, behavioral norms, and performance standards toward the elimination of harassment and discriminatory behaviors. It recognizes and rewards those who value, promote, and facilitate workplace diversity, and establishes an organizational culture and climate that is antagonistic to those who harass and discriminate.”

Diversity training and other initiatives need to be aligned with valid, ongoing measures of the organization's climate and culture. Wong suggests:

“The organization develops its diversity programming initiative based upon empirically derived assessment information about its workplace culture. Workplace assessment information allows diversity programming to utilize the "strengths" of the organization to overcome the "barriers" to inclusiveness. It capitalizes on the "opportunities" for change while vigilant in terms of the divisive issues that could bring unexpected conflict within the organization. The organization listens to the voices of personnel and customers.”

All diversity activities must be fully and visibly supported by management.

The objectives, content, and approach are customized to the organization's needs, rather than off the shelf. In some organizations, a comprehensive approach to diversity is appropriate; in others, a more focused, limited approach.

“The organization recognizes and articulates the "extremely compelling" needs and reasons (from the unique perspective of that organization) for diversity programming Initiatives. The services and business connections need to be made. The organization links and aligns its diversity goals to corporate strategy.”

Whatever the content of the diversity training program, it should be mandatory for managers.

Diversity programs should be preceded and accompanied by internal marketing and organizational communication efforts, to clarify the organization's goals, objectives, and expected outcomes. Wong recommends that a question and answer brochure on diversity be distributed to employees, and that principles and sample letters be widely available:

“Guiding principles for diversity are provided to management and personnel. These are simple communications that provide a rationale for supporting diversity. Model diversity letters for executives and managers to send to their subordinates reflecting the organizations posture and initiatives are provided annually. This expedites communication, making it easier, consistent and more likely to actually get done. The organization communicates effectively to create buy-in; then it communicates more.”

Diversity training must be followed up by supplemental training and/or “task teams” that review progress toward goals and develop additional follow-up activities. Diversity management should be incorporated into other management and leadership development training activities in the organization. Diversity should be a part of the “people skills” taught to managers through executive coaching, mentoring, and/or diversity leadership and management seminars. The organization establishes a process for reporting of diversity issues and for resolving diversity problems when they arise.

People's expectations about the outcomes of diversity management must be managed through ongoing discussions about what the program involves, what can be achieved, and when.

Wong recommends using internal and outside consultants, to supplement the organization's resources and provide a more objective perspective than can be achieved by inside personnel. The greater the clarity of the organization's goals for diversity, the more consultants can be helpful.

Diversity programs require clearly stated outcome objectives for the whole organization, and its business units and groups. The organization has a process of monitoring its diversity initiatives and holding managers accountable for activities and achievement of outcomes. Metrics must be used to assess diversity training results and organizational impact. Further:

“The organization develops benchmarks and "best practices" comparisons. Most have developed "internal" best practices (within-organization best practices). There are a few "industry" best practices comparisons (to include the same or different organizational functions and to include competing and/or non-competing organizations).”

Denny's Franchise Growth Initiative (FGI) program began in early 2007. FGI is a strategic initiative to increase franchise restaurant development through the sale of certain geographic clusters of company restaurants to both current and new franchisees. As a result of the FGI program, between 2006 and 2011, Denny's has decreased company-owned restaurants by 315 and increased franchised/licensed restaurants by 455. As of Dec 28, 2011, Denny's net increase in total number of locations since 2006 is 140.

Denny's reported gains on sales of assets is primarily dependent on the number of restaurants sold to franchisees during a particular period, and as a result, can cause fluctuations in net income from year to year. As Denny's nears the completion of their FGI program, gains on sales of assets, will continue to decrease.

As a result of the FGI program and a $100 million loan program with two lending partners to offer third-party lending to franchisees, since 2006 Denny's has transitioned from a portfolio mix of 66% franchised and 34% company-operated, to a portfolio mix of 88% franchised and 12% company-operated restaurants (see Table 4.) Denny's targeted portfolio mix is 90% franchised and 10% company-operated, and in 2011 Denny's reported they are currently on track to achieve this goal by the end of fiscal 2012.

Denny's has also recently signed two agreements to spur franchise growth through global expansion. The first agreement is with Great China International Group, with plans to open 50 new restaurants in China over a 15-year span, the first opening in 2012. The second agreement is with Musiet Group for the opening of 10 new restaurants in Chile; again over a 15-year span and with the first restaurant opening in 2013.

Company restaurant sales have decreased from $904 million in 2006 to $411.6 million in 2011, primarily as a result of the sale of company-owned restaurants to franchisees. The decline in company restaurant revenues is partially offset by annual increases in franchise and license revenue. Franchise and license revenue has increased 41.5% since 2006, from $89.6 million in 2006 to $127 million in 2011. For the third quarter of 2012, total revenues declined 11.6% to $120.9 million, down from the prior-year quarter's $136.7 million. Sales at companyoperated restaurants declined 17.3% year over year to $86.6 million. Franchise and license revenue increased year over year by 7.3%, to $34.4 million.

Since 2006, Denny's net operating income has averaged 9.91% of total operating revenue. Denny's net operating income for 2011 is 9.47%.

Interest expense has a significant impact on Denny's net income as a result of their indebtedness. Over the past several years, Denny's has continued to reduce interest expense through a series of debt repayments using the proceeds generated from their FGI transactions, sales of real estate and cash flow from operations. These repayments resulted in an overall interest expense reduction of 65.3% since 2006. The lower debt balances and lower overall interest rates on their debt have continued to positively benefit Denny's financial performance since 2006.

Denny's total assets have consistently declined since 2006, primarily as a result of property sold to franchises. However, as a result of $75 million in deferred tax assets for 2011, Denny's total assets were up 12.63% from the prior year, which was the first year, an increase in assets was shown since at least 2006.

Denny's total liabilities have decreased 46% since 2006. In 2011, Denny's debt ratio was 1.03, compared to their Top 4 competitors who had an average debt ratio of .675. Denny's liabilities have consistently decreased year over year, at an average of 11.5% per year since 2006. In 2011, their total liabilities were $360.1 million, down 13.19% from 2010.

A negative working capital position is not unusual for a restaurant operating company.

The 30% decrease in working capital deficit from 2006 to 2011 is primarily due to the sale of company-owned restaurants to franchisees as a result of the FGI program.

From 2006 to 2010, Denny's consistently maintained deficit balances for retained earnings and total equity. In 2011, for the first time, Denny's had a credit balance of $15.8 million in retained earnings. A 2011 acquisition of $25.5 million in Treasury Stock left them with a much reduced equity deficit balance of only $9.7 million for 2011; a 91% reduction in deficit from 2010, and a 96% overall deficit reduction since 2006.

Denny's 2011 net income per share increased 400% from 2010 as a result of $83.9 million in tax benefits realized from the release of the majority of Denny's valuation allowance for tax deferred assets. As of Dec 2011, Denny's net income per share was $1.15, up 248% from 2006.

A, B, and C answers are provided to the questions below.

Diversity: general protection and inclusion of employees' attributes going beyond those mandated by law (e.g., race, sex, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, age, and disability) within the context of a palpable workplace diversity culture that embraces employees' individual attributes. Denny's diversity strategy extended to external customers and vendors to make it a pivotal aspect of its operations.

Managing diversity: the implementation, coordination, and management of organizational actions to foster diversity

Workplace diversity referred broadly to the protection, respect and inclusion of the entire package of attributes that each employee contributed to the workplace (Denny's, pp. 6). Jim Adamson's four part strategy on obtaining diversity included:

Managing diversity for Denny's (Denny's, pp. 9-10) included measuring systematically its performance on a number of diversity indicators. Results show:

In the early 1990s, diversity at Denny's was a trivial strategic business ideology of providing fair treatment to its employees and customers of diverse racial, ethnic, and religious background. In the recent years, Denny's considered the indicators of diversity such as; age, gender, marital status, sexual orientation, and disability through a new reconstructive anti-discrimination plan. Furthermore, managing diversity was not a crucial issue on the agenda of the business management team. It was not directed to add a social value to the reputation of Denny's. The management system did not provide any diversity training and, for some odd reason, only few minorities were able to occupy management positions. Denny's wanted to enhance its image in the society and recapture the portion of the market share that was lost to rivals.

Adamson made it his priority to provide better jobs for minorities and women (Denny's, pp. 7) through his fourpart strategy, and by getting rid of employees at all levels who failed to embrace the diversity initiative. In 1995, Adamson hired Rachelle Hood-Phillips as Chief Diversity Officer (the nation's first diversity manager to answer directly to the CEO) (Denny's, pp. 7-8). Hood instituted mandatory diversity-training sessions for every worker at every level; developed initiatives to monitor progress in every area of operations; paid close attention to the strategic decisions and actions of senior management and board members; pushed buyers to dole out business to minority-owned companies ($616 million with minority suppliers from 1995 to 2000); and made charitable contributions to minority-related organizations ($1.3 million to civil and human-rights causes; recruitment at historically black colleges; “Re-ignite the dream campaign.”)

Denny's CEO, Jim Adamson, implemented a four-part strategy for Denny's cultural construction:

Denny's Corporation implemented new social and cultural changes within the organization based on new recommendations and guidelines from Adamson and Hood to adopt strategic plan of diversity and to regain public reputation and sales. Adamson, Denny's CEO, decided to reconstruct Denny's organizational culture through a four-part strategy that was enforced to:

The lack of diversity policies made the company lose a strong competitive advantage. Denny's Corporation decided to change its organizational culture by teaching its employees the proper scheme in managing workplace diversity. Ray Hood-Phillips, the diversity manager, emphasized on diversity initiatives across the organization at all levels of management and terminated any employee who failed to follow the diversity plan. The performance reviews for senior managers concentrated on valuing diversity management.

Evaluate Denny's practices for creating and managing a diverse workforce.

a. Practices could be adopted by other organizations:

b. What practices are probably specific to Denny's unique situation?

c. What changes would you make in HR practices?

“Diversity was a recognizable source of creativity and innovation that could provide a basis for competitive advantage. On the other hand, diversity was also a cause of misunderstanding, suspicion, and conflict in the workplace that could result in absenteeism, poor quality, low morale, and loss of competitiveness.” (Denny's, pp. 11)

Diversity became more of something that people had to do or face the consequences, than something people wanted to do and embrace

Ray Hood-Phillips was the first diversity manger to report directly to the CEO.I would prefer the diversity manager to report to the HR Department head. Despite the importance of the issue, the CEO should neutralize the internal threats of creating favoritism and inequality among the managerial ranks before addressing the discrimination and external threats. For managers who refused to comply with diversity policies, the CEO decided to withhold up to 25% of their bonuses. I see it as a temporary, unfair, inefficient, and counter-productive approach. Behavioral control factor through compensation enticement policies should be in place instead of compensation punishment and retribution which brings only negative consequences.

Denny's has resolved its problems of discrimination to a great degree. However, the 2006 Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) lawsuit against Denny's for violations to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for failure to reasonably accommodate a disabled manager, indicates Denny's “neglecting” this protected group. Since disabled individuals represent the largest minority group, Denny's should ensure that all of its successful strategies to enhance diversity include disabled employees and applicants.

Denny's became a recognized workplace diversity leader. Denny's reached an advanced level of employees' awareness regarding sensitivity and diversity issues. A new team instituted company-wide training programs and restricted policies that enhanced the diversity of Denny's employees and customers. The action translated the Corporation's vision of prohibiting discrimination against minority workers and clients. The Company spent as much as $14 million in one year on marketing strategy aimed at attracting minority clients. Denny's must answer the question: Did the firm exploit the opportunity of adding a social value and eliminate the threats of discrimination law suits to score a competitive advantage? The company should identify and develop a strategy that balances diversity and business performance as two conflicting issues. This conflict possesses a considerable potential to strengthen or weaken the overall competitiveness.

Denny's financial statements for the period 2007-2012 show mixed results as the company has transitioned from owning the majority restaurants to owning far fewer locations and franchising the bulk of locations, as outlined in the Franchise Growth Initiative (FGI) program that began in 2007. The recent financial crisis and its effect on consumer spending habits also must be taken into account when analyzing the financial statements of any company that is dependent on the discretionary spending habits of consumers.

Profitability ratios are used to measure a company's ability to earn an adequate return in relation to the amount of sales in a period or the assets and resources used in normal operations. In regards to Denny's financial statements for the years covering 2007 – 2012, the firm has shown mixed results. Return on Assets (ROA) has for the most part declined, dropping from 8.44% in 2007 to 6.62% in 2012. ROA for 2011 was unusually high 34.03%, but this can mostly be attributed to the large dollar amounts of release of valuation allowance and benefits for income tax which increased net income to an amount ($112,287,000), which is much higher than any other year in the period covered. Return on equity (ROE) has remained steady throughout the six year period, although not at good rate, with an average ROE of less than zero. This can be attributed to Denny's increased holdings of treasury stock and a total shareholder's deficit in each of the six years covered. Denny's earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization ratio (EBITDA) has remained fairly steady throughout the period, averaging 14.26% over the six year period and 14.49% for 2012 (Bramhall 2007).

Denny's ratio of current assets to current liabilities and ratio of quick assets to current liabilities, measured by the current ratio and quick ratio respectively, have remained fairly consistent throughout the six year period. Decreased property amounts have for the most part been offset by increased receivables from franchises and other sources. Debt management at the company has also been consistent, with both long-term debt to equity and total debt to equity ratios being less than zero for the entire period. This would appear as good news for both current and potential creditors. In addition, interest coverage increased to a six year high in 2012 of 3.69% (interest coverage was its lowest in 2009 at 1.63%), which should provide additional assurance for potential creditors.

It would appear that Denny's has been somewhat inefficient in managing its assets, as total asset turnover has steadily declined from a high of 2.28 in 2007 to a low of 1.45 in 2012, due to inconsistent net income and total asset numbers. Likewise, the company's receivables turnover rate decreased dramatically from 66.93 in 2007 to 28.05 in 2012. However, because the number of company- owned restaurants has decreased dramatically while the number of franchise-owned restaurants has increased under the FGI program, it should be expected that there would be a decrease in the receivables turnover.

On the surface diversity has been achieved at Denny's, women and minorities make up half of their eightmember board of directors, and 45% of the 11-member senior management team. From 2002 to 2007, the company remained at or near the top of the Fortune Best Company for Minorities list (Denny's, pp. 10). However from 2006 to 2007, sales continued to decline. (Denny's, pp. 12). At this point, I believe the decline in sales has more to do with service than with diversity. With every Denny's, I go to the workers, almost consistently act like they hate their jobs… and in turn hate having to wait on their customers. These experiences stay in a customer's mind. This is echoed in a New York Times article. ''One of our problems here at Denny's is our last users,'' he [Nelson J. Marchioli] said. ''Everybody knows about us, but there's a lot of people that won't come back because of bad service. We have not set a good example as it relates to service, hospitality and cleanliness in the restaurant business.'' While Denny's has been successful in diversifying it's staff, there seems to still be a lot more work to be done. The company needs to focus on training its diverse staff now on customer service. In the end, if the customers does not like what they get at one restaurant (or store, bank, hospital, etc.) they will go to another… there are plenty more fish in the sea!

(a) The number of lawsuits and legal problems had considerably declined.

(b) Denny's recognized as leader in diversity (great public relations outcome).

( c) Long term likely positive outcomes: a diverse workforce allows for richer perspectives including new services and products to be offered resulting in new business opportunities.

I conclude that for the most part, the answer is “true.” The reasons offered for “false” answer correlate with the slowing down of the American economy of the last few years. The third reason above for “true” may reflect a competitive advantage likely to lead to financial success.

Managing workforce diversity was Denny's vision to gain a racial anti-discrimination activist reputation which consequently will generate a competitive advantage. The inaccuracy of such argument revolves around the outcomes of diversity which caused misunderstanding, suspicion, and conflict in the workplace. Indirectly, it created a level of leniency towards worker's absenteeism, poor quality, low morale, and loss of competitiveness. The answer is in finding equilibrium. Diversity emphasis was a temporary focus to overcome historical circumstances. Knowing that the situation has improved, Denny's should not ignore diversity, but ought to shift the focus towards business practice and financial earnings. Without stable financial revenues, Denny's cannot exploit any sources of sustained competitive advantage.