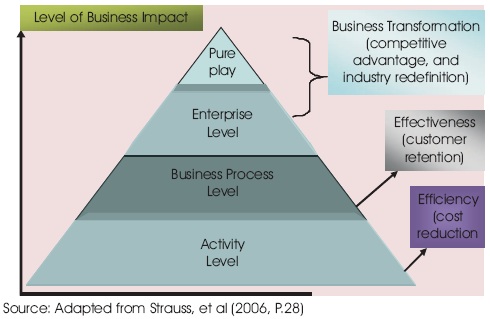

Figure 1. Level of EM Implementation

The literature reflects that little effort has been made to develop a framework for understanding the effect of e-marketing (EM) on the marketing performance of business enterprises. The main objectives of the study are developing propositions and theoretical framework constructions rather than theory testing. The author, thus, synthesizes the extant knowledge on the subject by providing foundation for future research by developing propositions and constructing an integrated framework that includes the antecedents and consequences of e-marketing implementation. More specifically, the author identified two important classes of variables that encourage or impede the adoption and implementation of e-marketing namely external and internal related variables and impact EM has over the marketing efficiency, effectiveness and performance on the Medium and Large Business Enterprises in developing countries a case of Ethiopia. The author also indicated the managerial implications in the competitive marketing environment. Finally, the conclusions and further research scopes are forwarded.

E-Marketing (EM) is the use of information technology in the processes of creating, communicating and delivering value to customers, and for managing customer relationships in ways that benefit the organization and its stakeholders. In simple term, EM is the result of information technology applied to traditional marketing. EM affects traditional marketing in two ways. First, it increases efficiency and effectiveness in traditional marketing functions. Second, the technology of EM transforms many marketing strategies. The transformation results in new business models that add customer value and/or increase company profitability (Strauss, et al, 2006). Given these widely acknowledged importance, one might expect that the concept of EM has clearly understood and internalized by marketing practitioners, and it has rich theory developments and related body of empirical findings. On the contrary, a close examination of the literature reveals a lack of clear understanding by marketing practitioners, little careful attention to measurement issues and virtually no empirically based theory. Further, the literature pays little attention to the contextual factors that may affect the implementation of EM for business enterprises. It is from this point of view that the researcher would like to address this relative gap by developing the conceptual model that will create a clear picture of the interrelationship between e-marketing implementation and the marketing performance of medium and large business enterprises in Ethiopia here thereof.

In today's business environment, most organizations face developing an e-business (EB) strategy (traditional business strategy plus information technology). Almost all regions in Ethiopia Business Process Re-engineering, BPR, is implemented; organizations are redesigning their internal structure and their external relationships, creating knowledge networks to facilitate improved communication of data, information and knowledge while improving coordination, decision making and planning. These new intra and inter-organizational relationships are based on new economy technologies not available just a few years ago. Such knowledge-based organizations are structured through the application of EB and EM systems to cope up, meet the ever-changing needs of the society, and serve the customers more than what their competitors do. To do these, the business enterprises should adopt and implement electronic systems successfully though there are so many factors affecting its effective implementation.

The factors that affect the adoption of EM by businesses have been the subject of much scholarly debates. The studies, which have been conducted in the area, have largely had a management focus on various theoretical business models and application models for EM (Bakos, 1998; Grieger, 2003; Lee and Clark, 1997). Very few investigators have investigated the practical applications of EM (Gottschalk & Abrahamsen, 2002); and the role-played by it via Internet applications (Bakos, 1998). Numerous studies examined the influence of environmental factors on success of information system planning. For example, Kearns and Lederer (2000) investigated that environmental uncertainty is an important contextual factor influencing strategic information system planning success. The key to make the most appropriate use of EM is to ensure that organizational and system changes stay one-step ahead of the competition. Effective strategies towards the adoption of EM needs to be based on good understanding of the costs and benefits using “virtual world” technologies, (Fraser, et al, 2000).

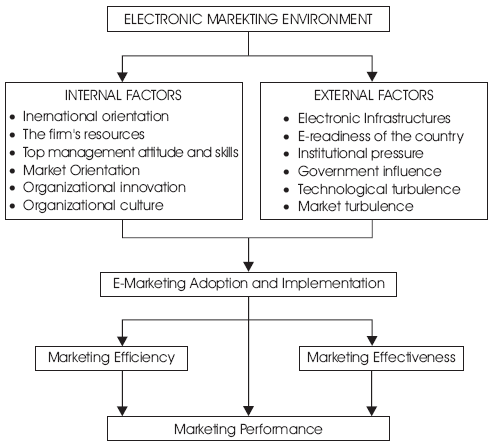

According to Fills, et al (2004) globalization, technology, competitive pressure, government policy, size of the firm, business competencies, etc are listed as macro and micro factors that affect the adoption of EB. On the other hand, Chan and Suliman (2002) emphasized on the government's role for the successful adoption and implementation of EB by many organizations. These all factors indicate that modern firms face an increasingly more complex and competitive marketing environment than ever before. Besides, organizational capabilities and technological innovation are major challenges and crucial to firms success and adoption of EM (Tornatzky and Fleischer, 1990; Veliyath and Fitzgerald, 2000). Despite these range of studies there have been very few studies on factors that influence enterprises in their adoption of EM. Especially in developing countries the factors that influence the adoption of EM system and the benefits it has are not yet understood and internalized. Organizations in such countries usually adopt and implement EM system only without having a full scale of understanding as to how it will affect the marketing and business performances of organizations. Thus, from these points of view that the researcher tries to address this relative gap by developing the following conceptual model to create a clear picture within academicians and practitioners regarding EM's impact on business enterprises' performance. The following is the conceptual framework for the development of research propositions. Briefly, the framework comprises three sets of variables. The first one is the antecedent conditions that foster or discourage EM adoption and implementation. The second one is the EM adoption and implementation construct, and the third one is the consequences of EM adoption and implementation. The researcher tries to discuss each of the three factors and develop research propositions based on the literature reviews in the field and facts from the textbooks and proceedings.

Antecedents to EM adoption and implementation are the external and internal related factors that enhance or impede the implementation of EM within the business enterprises in Ethiopia. The researcher examined a wide area of related literatures and got insight as to the classification of antecedents as internal and external related variables. The internal factors include international orientation, the firm's resources, top management attitudes and skills, market orientation, organization innovation and organizational cultures while the external factors include electronic infrastructure, e-readiness of the country, institutional pressure, government influence, technological turbulence, and market turbulence. Here below are the detail discussions and the development of principal Propositions (PP) and sub-propositions (SP) of the factors/variables under study.

In the globalized marketing scenario, many firms are looking the outside market in order to maximize their sales revenue via tapping the untapped markets. Globalization is now a massive and forceful process that is unlikely to be stopped. Therefore, the nature of business in today's marketplace demands firms to interact with their customers and business partners using technology to provide services instantaneously across international borders. Kotler (2000) indicated that the Internet eliminates the economic consequences of geographic distance to insignificant levels, which opens up substantial opportunities for reaching international as well as domestic markets. Companies must relate the traditional face-to-face interacting via a technology interface. Advances in technology have revolutionized the way in which businesses are conducted in a new economy (Aziz and Yasin, 2004). Business enterprises as part of the global economy have to cope up with globalization and its effect on businesses activities all over the world. Most of the time business organizations state their long-term objectives as to be one of the big international enterprises in the world. To meet this objective, the enterprises should maintain the relationship marketing strategies, the just-in time manufacturing philosophy and maintaining effective communications with suppliers, customers, agents and distributors. In this respect, EM can be the right way to improve the firm's ability to develop and reach international market.

From the researcher's point of view, the more international oriented the business enterprises are, the greater likely to show responsiveness to internet based technology and EM to satisfy the ever changing needs of their customers and to face the effects of competitors' action. This leads to the proposition of:

SP1: There is a positive significant relationship between international orientation and the firm's EM implementation.

The availability of resources could be one of the vital factors in adopting and implementing EM by medium and large business enterprises. The traditional industry analysis approach focuses on the importance of industry structure and market positioning of organization (Porter, 1990); however, the newly emerged resource based view has emphasized on each firm's unique resources, core competence and dynamic capabilities in a rapidly changing global market (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). In this resource-based view, a firm's competitive advantage itself rather than external environments is the primary source of firm's profitability (Grant, 1991). Barney (1991) classified firm resources in to physical capital resources, human capital resources and organizational capital resources. Moreover, he pointed out that resources include all assets, capabilities, organizational resources, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc, which were controlled by a company that enables it to conceive and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness. Firms obtain competitive advantage due to the presence of one or more resources that allow for products and services differentiation or even uniqueness that is valued by one or more customers (Gouvea and Kassicieh, 2001).

The researcher argues that the decision to adopt and implement EM depends in most cases on the availability of financial resources since the technological infrastructure and the technical resources require a substantial amount of financial resources. The organization need to have sufficient budget for the development of EM tools (that is designing and launching of a web site, internet connection, etc), to provide training for the employees, to provide the hardware and soft ware needed, and maintenance of the system. Every system is built and used by people. Thus, the human resource is also the mobilizing factor of the company's resources. If the human factor is not extensively considered in the process of system development, the system may fail and thereby the organization's investment becomes wasteful. The technology by itself will do nothing; it is dependent on the human factors. To be successful, the firm needs to have skilled manpower and technical expertise that can make the technology more usable in the organization. To have all these resources, the organization is expected to invest certain amount of money in the areas of technical resources and human factors of the organization. It is from this point of view that the researcher considered the firm's resources as one of the deriving or impeding factor to adopt and implement EM to tap the opportunities exist in the globalized marketing environment. This leads to the development of the proposition as:

SP2: The greater the resources the firm has, the more likely to adopt and implement EM within the organization.

The role of senior management emerged as one of the most important factors in fostering EM implementation. Interestingly, the management literature goes a step further to provide novel insights. Argyris (1966) argue that a key factor affecting junior managers is the gap between what top managers say and what they do. For example, they say “be customer oriented” but cut back market research funds and discourage changes. If top managers demonstrate a willingness to take risks and accept occasional failures as being natural, junior mangers are more likely to propose and introduce new offerings in response to changes in customer needs. Moreover, Hambrick and Mason (1984) view that organizations headed by top managers who are young, have extensive formal education and are of low socioeconomic origin are more likely to pursue risky and innovative strategies. Thus, a positive attitude toward change has been linked to individual willingness to innovate. And the willingness to adapt and change marketing programs on the basis of analyses of consumer and market trends is a hallmark of customer focus firms. The researcher therefore expects that:

SP3: The more positive the senior mangers' attitude toward change and greater managers' skills, the greater the EM implementation within the organization.

Theoretically, a market driven firm constantly monitors the environment in which it competes in order to learn the appropriateness of its offering to its target customers. As the customers' needs and perceptions on the firm's and/or its competitors' offerings constantly change, it is imperative to routinely evaluate one's competitive status and make timely decisions on needs modifications to offerings and marketing campaigns (Chang, et al, 1999). A customer-oriented manager learns to seek information from customers about their perceptions and takes actions based on that information in consideration of competition and regulations to ensure superior performance (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Slater and Narver, 1994). “A market oriented company continuously studies various means of improving its offering quality and enhancing sustainable superior value for its buyers” (Chang, et al, 1999, P.408). To accomplish this objective, marketers must have sufficient knowledge of buyers' cost and revenue structures as well as the nature of the derived market (Narver and Slater, 1990).

According to Kohli and Jaworski (1990, P.6) “market orientation is the organizational wide generation of market intelligence pertaining to current and future customer needs, dissemination of the intelligence across departments, and organizational wide responsiveness to it”. Consequently, market orientation contributes to continuous learning and knowledge accumulation by an organization, which continuously collects information about customers, competitors and uses the information to create superior customer value and competitive advantage (Slater and Narver, 1990). Interestingly, it appears more appropriate to view a market orientation as a continuous rather than a dichotomous either or construct. In other words, organizations differ in the extent to which they generate market intelligence, disseminate it internally and take action based on the intelligence. Thus, to create exception value for their customers by being market oriented, it calls in turn the application of information and communication technology within the organization and it is one of the tools of EM in the globalized marketing environment. This leads to the proposition of:

SP4: There is a positive relationship between market orientation and the firm's implementation of EM.

In today's era of economic knowledge, strategies must be focused on expanding existent markets or creating new markets (Kim and Mauborgne, 1998). The past ways of business management cannot assure that they can provide firms with competitive advantages (Lei, et al, 1999). Continual innovation is the only way for firms to obtain a winning position in the competition (Hoffman, 1999). Becoming an innovative organization is a means to compete in this dynamic and changing business environment (Dooley and Sullivan, 2003). As revealed by several researchers in the field, innovation is one of the paths to maintain growing and promising organizational performance (Cottam, et al, 2001). It is also pinpointed as an essential element for sustaining competiveness and ensuring an organization's future potential (Krause, 2004).

Schepers, et al (1999) contends that continuous growth is the main factor for almost all-organizational success. Innovation is the principal factor to trigger business growth. Only firms can continually create new products, systems, and service items to make every department meet the needs of the customer, will be able to obtain long-term success (Chang and Lee, 2008). According to Higgins (1995), the largest property of twenty-first-century firms lies in their capability for innovation. Innovation will definitely bring individuals, teams, organizations, industries or societies better values and may provide a firm a relatively low cost production process, in good control of the tips with competitive advantage. Guinet and Pilat (1999) also suggest that the reason large firms have been able to survive without any innovation in response to changes in their economic environment is only because of their successful product lines. However, in the current global competitive business climate, despite the business scale, no innovation means a very slim chance of survival. Thus, every department in every firm must keep up their innovation activities in order to sustain business growth and taking the lead in the market place.

With the rapid improvements in technology and the volatile economic environment, knowledge management has become a necessary and critical part in the enhancement of a firm's competence. In this environment of rapid changes and uncertainty, where the demands of the markets keep changing, the only way for an organization to make a breakthrough and obtain a competitive advantage is through knowledge accumulation (Chang and Lee, 2008). This shows that by establishing excellent knowledge management systems, it is possible for a firm to make good effective use of its own resource so that they can accumulate business management experience and reach their goals for organizational innovation. Slater and Narver (1995) further proposed that innovation of the core activities must be correlated with the orientation and performance of the lead market.

From the researcher's point of view, the level of relevant knowledge accumulation, organizational innovation and even organizational culture and performance are all deeply affected by the technological environment surrounding an organization. Information technology is gradually turning the world in to an information highway network. The development of technology has greatly accelerated the international flow of information, capital and commodities and speeded the growth of economic integration. The executives can best monitor internal and external factors, that is, how to effectively absorb external knowledge and how to integrate their own knowledge and creatively, and create new techniques, new products and new management ways are best addressed through the implementation of information and communication technologies within the organization which are the best tools of EM system. From this point of view, the researcher proposed the following sub-proposition as:

SP5: There is a positive relationship between organizational innovation orientation and the firm's EM implementation.

Today, the business environment is changing fast. The changes in technology like computerization and EM have created a quantum leap in data communication, work process and the way doing business. With the impending move toward globalization and liberalization of markets, organizations have to be prepared to cope up with the rapid changes in the business dynamics. Many organizations found change to be a real challenge. The change process in each organization is unique in each situation, due to the differences in nature of the organization, the nature of the business, the work culture and values, management and leadership style and the behavior and attitude of the employees (Abdul Rashid, et al, 2004).

The major reasons for the wide spread popularity of an interest in organizational culture stems from the assumption that certain organizational cultures lead to superior organizational financial performance (Ogbonna and Harris, 2000). Similarly, many academicians and practitioners argue that the performance of an organization is dependent on the degree to which the values of the culture are widely shared, that is, are “strong” (Knapp, 1998; Denison, 1990; Kotter and Heskett, 1992). They claim that organizational culture is linked to performance and is founded on the perceived role that culture can play in generating competitive advantages (Scholz, 1987). Krefting and Frost (1985) suggest that the way in which organizational culture can create competitive advantage is by defining the boundaries of the organization in a manner, which facilitates individual interaction, and/ or by limiting the scope of information processing to appropriate levels. Similarly, widely shared and strongly held values enable management to predict employee reactions to certain strategic options thereby minimizing the scope of undesired consequences (Ogbonna, 1993; Ogbonna and Harris, 2000).

Atkinson (1990) explains organizational culture as reflecting the underlying assumptions about the way work is performed; what is acceptable and not acceptable'; and what behavior and actions are encouraged or discouraged. More specifically, it is the collection of traditions, values, policies, beliefs, and attitudes that constitute a pervasive context for everything we do and thing in an organization. While often originating from senior mangers' beliefs, organizational culture takes on a meaning when beliefs are shared amongst employees (Rapp, et al, 2008). Organizational culture can be either supportive or unsupportive of organization initiatives. It also has the potential to influence employees' ability or willingness to adapt or perform well (Weick and Quinn, 1999). This is particularly salient given that many firms and employees are hesitant to undertake new technological advancements (technological phobic). Consequently, cultivating an organizational culture that supports the implementation of technological advancement is an important consideration for firms when implementing EM applications.

Thus, organizational culture can function as either an internal facilitator or a barrier with the potential to enhance or impede the implementation of a new technology. Employees are sometimes reluctant to embrace change (Rapp, et al, 2008). Accordingly, it is important for a firm's top management team to shape and communicate the visions and strategies necessary for a successful EM implementation. Their actions send signals that cascade throughout the organization and influenced by the change. Combined, the top management teams' beliefs and participation in the organization shapes the culture within the organization. This culture can then enable employees to legitimize the implementation of a new strategic approach to the customer. Based on these arguments, it follows that a firm with an organizational culture that is open to change, EM and technology will be more likely to embrace its implementation.

SP6: An organizational culture open to change and EM will have a significant positive influence on a firm's implementation of EM.

The availability of good and sufficient electronic infrastructure is not only one of the vital factors of EM adoption and implementation but also the backbone of it (El-Gohary, et al, 2008). Without good, sufficient and affordable electronic infrastructure there is no EM, EC or EB. Most of the studies in the field considered adequate IT and electronic infrastructure as a vital factor in success for EM efforts (Naude and Holland, 1996; Phan and Stata, 2002; Samiee, 1998).

According to Mesenbourg (2001), electronic infrastructure can be defined as “The share of total economic infrastructure used to support electronic business processes and conduct electronic commerce transactions.” He further states that it includes hard ware (computers, routers, satellites, wires, optical communications and network channels), software (system and applications software), telecommunication networks, support services (web site development and hosting, consulting, electronic payment, and certification services), and human capital used in conducting electronic business and commerce (such as programmers, practitioners and users). Electronic infrastructure can be measured by many measures such as number of internet and data service providers, the internet community (number of internet users within the country), number of computers per capita, number of land line per capita and density of communication technology and facilities (El-Gohary, et al, 2008). These technologies increase the abilities of the firm to communicate (internal and external) to the customers, channel members, and stakeholders in general, which will help the firm to gain competitive advantage over their competitors. Thus, the availability of these electronic infrastructures, which covers all areas of technology within a country, is the core facilitators for EM practices within the organization. This lead to the proposition of:

SP7: There is a positive relationship between the availability of electronic infrastructure and the firm's EM implementation within the organization.

The role of electronic networks has grown exponentially in recent years. There is a need to determine the factors that preclude firms from the electronic relationships in the globalized marketing environment. There are barriers to electronic business practices in one's country like network infrastructure and computer literacy, as well as cultural and socio-economic factors (Reddy and Iyer, 2002). These are, in general, referred to as E-readiness of the country's related factors.

E-readiness, the construct is defined as a country's ability to promote and support digital business and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services (Berthor, et al, 2008:701). A nation's e-readiness is, thus, a measure of its EB environment, and represents a collection of category indicators of how amenable a country is to internet-based opportunities (The Economist, 2006). More specifically, e-readiness includes connectivity and technology infrastructure, business environment, consumer and business adoption, legal and policy environment, social and cultural environment, and supporting e-services. Connectivity and technology infrastructure include narrow, broadband, PC and mobile phone penetration as well as internet affordability and security. The business environment comprises a series of indicators including strength of the economy, political stability, the regulatory environment, taxation, competition policy, the labor market, quality of infrastructure, and openness to trade and investment. Consumer and business adoption consists of national spending on ICT as a proportion of GDP, the level of EB development, degree of online commerce, quality of logistics and delivery systems, and availability of corporate finance. The legal and policy environment comprises factors such as overall political environment, policy toward private property, government vision regarding digital-age advances, government financial support of Internet infrastructure projects, level of censorship, and ease of registering a new business. The social and cultural environment consists of education level, Internet/web literacy, degree of entrepreneurship, technical skills of the workforce, and degree of innovation. Finally, supporting e-service refers to availability of EB consulting and technical support services, availability of back-office support, and industry –wide standards for plat forms and programming languages (The Economics, 2006). Thus, the researcher argues that when the country's e-readiness increases with quality services, the possibility of adopting and implementing EM within the organization increases. This leads to the proposition of:

SP8: There is a positive significant relationship between the country's e-readiness and the firm's EM implementation.

Organizational sociologists have long argued that firms adopt technologies because of institutional pressures from constituencies in their environment. This includes stakeholder pressure and competitive pressures. Stakeholder pressures are forces on the firm from its customers, trading partners, investors, bankers, suppliers, general public media, etc to adopt the technology. Some resource dependency theorists (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978) have argued that managers lack the power to do anything beyond allocating resources to developments and actions that customers require. On the other hand, competitive pressures force a firm to adopt a technology or risk losing competitive advantages (Abrahamson and Rosenkopf, 1993).

EB is fundamentally changing the way in which firms do businesses (Rapp, et al, 2008). According to Porter (1985), reaction to competitors is an important element of strategy formulation for companies of all sizes. Moreover, he reconsidered his writings on strategy in light of the Internet presence and concluded that increased adoption of the Internet will lead to increased competition within markets (Porter, 2001). It allows firms to compete with unprecedented levels of speed, connectivity, and efficiency as they share information exchange and goods and services. Despite these benefits, many firms implement EB and EM strategies not because of rational efficiency and improvement assessments, but because of the external pressures that derive from the large number of organizations that have already implemented the new technology (Srinivasan, et al, 2002). As organizations become more aware of the opportunities for greater access to new markets, increasing demands from existing customers, and advancements in EB initiatives made by competitors, firms perceive that EB is not simply being accepted in the market place, but rather is critical to firm survival and success (Rapp, et al, 2008).

Many researchers argued that firms could compete effectively by adopting EC (Campbell, 2000; Daniel and Myers, 2000). Daniel and Storey (1997), Daniel and Wilson (2002) and Poon and Jevons (1997) found out that competitive pressure is one of the main drivers of EC activities. Two underlying reasons for the implementation of e-market are evident. First, firms that do not implement an EB and EM strategy may be perceived as outdated. Many managers believe that it is necessary to respond to the external pressures present in the business environment or risk the chance of being viewed by customers, suppliers and investors as lagging behind the competition (Srinivasan, et al, 2002). Second, and more importantly, EM represents a separate and unique distribution channel to service customers. Many customers may demand that firms implement EM so that they get access to this additional channel, possibly simplifying the transaction process. Recent research has shown that incorporating additional marketing channels leads to an overall increase in total sales and has a net positive effect over any sales that may be lost due to cannibalization (Kumar and Venkatesan, 2005).

Thus, when these arguments are applied to EM technologies, an organization's early and extensive adoption signals its technological astuteness and gives it social legitimacy with its stakeholders. In addition, fear of being left behind competitors also results in technology adoption and implementation. Therefore, the researcher expects that:

SP9: The greater the institutional pressures on a firm to adopt a technology, the greater extent on a firm's implementation of EM.

Government can have a great influence on EM adoption and implementation by business enterprises. Javalgi, et al (2004) argue that in developing electronic economies, government involvement represents a critical driver of the diffusion of technological advancements, as well as the implementation of such technologies by firms. However, it is not enough for a country's government to only implement some guidelines and policies regarding the use of EB (Rapp, et al, 2008). It must also take some steps to remove any structural barriers that stand to impede EB initiatives (Javalgi and Ramsey, 2001).

The researcher argues that the government regulations and initiatives have considerable potential to influence whether firms implement EM technologies or not. As it is possible that government involvement will actually impede a firm's ability and/or desire to move towards an electronic channel to service customers, the researcher focuses on regulations that reduce concerns about security risks and initiatives that promote EM activity. Thus, a firm's implementation of EM is likely to depend upon the extent to which the embedding government informs, provides incentives and protects the firm with supportive regulatory initiatives. Consequently, the researcher proposed as:

SP10: Government regulations and initiatives that support EM applications will have a significant positive influence on a firm's implementation of EM.

Firms increasingly rely on external knowledge to foster innovation and to enhance their performance (Reuer and Singh, 2002). A firm's innovation processes are embedded in an environmental context (Jansen, et al, 2006). As turbulent environments increase causal ambiguity, competitors' ability to imitate a firm's capabilities decreases, and this limitation may help firms to achieve superior innovation and performance based on their dynamic capabilities (Song et al, 2005). According to Kohli and Jaworski (1990, P.14) technological turbulence refers to rapid changes in “the entire process of transforming inputs to out puts and the delivery of those out puts to the end customers”. Jaworski and Kohli (1993, P.57) also contend that technological turbulence refers to “the rate of technological change.” Thus, technological turbulence can be defined as the degree to which technology changes over time within an industry, in production as well as in the product itself.

The researcher argued that globalization intensifies competition all over the world. Businesses nowadays are not just facing challenges from cost to quality. Gaining customer loyalty is a great challenge in these days marketing environment. In order to satisfy their customers' unlimited expectations, companies need to orient themselves to their customers' wants, as well as latent needs and as a result provide products and services, which are perceived to be valuable. Because these customers needs, wants and expectations continually evolve over time with the change of technology, delivering consistently high quality products and services requires ongoing tracking and responsiveness to changing market places. That is, the firm should deploy information technology on the traditional marketing practices to tap the ever-changing needs and wants of consumers more than what competitors do. Thus, organizations that work with nascent technologies, and are undergoing rapid change may be able to obtain competitive advantage through technological innovation. From the above discussion, it is possible to say that:

SP11: The greater the technological turbulence, the greater likely to implement EM within the organization.

Managers face environmental turbulence in terms of the emergence of new proprietary technologies, rapidly changing economic and political trends, changes in social values and shifts in consumer demands (Karake, 1997). One aspect of environmental turbulence is market turbulence. Market turbulence arises from the heterogeneity of the market, and the resulting rapid changes in customer composition and thus customer preferences. Market turbulence refers to “changes in the composition of customers and their preferences” (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990 P. 14).

More and more, information and information technology are viewed as assets that, if managed properly, would undoubtedly improve both efficiency and effectiveness and sharpen organizational focus. Corporations are discovering as information technology resources contribute to the values added of their products and/or services. As a result, major corporations are increasingly deploying IT as one of the key elements of their strategies (Karake, 1997) so that mangers can do decisions and take proactive measures on timely basis. Information technology affects the entire organization from its design and structure to product market strategy. And the application of information technology on the traditional marketing practices is the central theme of EM. In order for top managers to properly interact with the dynamic aspects of a turbulent market environment, they tend to move towards a formal way of managing their market environment.

From the researcher's point of view, change and market turbulence means that organizations must gather more information about their marketing environments. More turbulence raises the amount of information that is required to successfully manage the change in consumers' preferences change and changes in social values. Market turbulence increases the need not only for more information, but also for more organized, comprehensive, accurate and timely information. To better manage the market turbulence, it calls the application of EM. It is argued that with high market turbulence and competitive intensity, it is crucial continually to gather and utilize market information to adapt adequately (Ottesen and Gronhaug, 2004) and hence the sub-Proposition is:

SP12: The need for EM implementation is positively correlated with the increase of market turbulence.

Therefore, from the above detailed discussions based on related literatures and facts from published books and proceedings, the researcher developed the following principal propositions.

P1: The adoption and Implementation of EM is dependent on the internal factors of the firms.

P2: The adoption and implementation of EM is significantly influenced by the firms' external factors.

The revolution in Information Technology (IT) and communications changed not only our day-to-day life but also the way people conduct business today. In recent year, increasing numbers of businesses have been using the Internet and other electronic media in their marketing efforts, giving the chance for EM (as a new marketing phenomenon and philosophy) to grow in a very dramatic and dynamic way. The rapid proliferation of the Internet, the World Wide Web (WWW) and electronic communication has created fast growing new electronic channels for marketing. This rapidly expanding use of the Internet and other electronic communication for business purposes attracts companies to invest in online presence (Liang and Hung, 1998). Internet technology has a direct impact on companies, customers, supplier, distributors and potential new entrants in to an industry (Porter, 2001).

EB, EC, and EM have been promoted as the savior of the business world and a catalyst to twenty-first century performance in the global market place (Fills, et al, 2003). Discussions normally centers on how information technology can be used to improve the reach of formalized business and marketing approaches to a much wider customer base than ever before. It has been suggested that embracing technology can result in gaining competitive advantage and capitalization of the opportunities resulting from the globalization of business (Levitt, 1983). Today, technology has advanced at a much faster rate than was previously imagined, offering vast opportunities for instant international market access, as well as improved domestic market performance (Keogh, et al, 1998; Coviello and McAuley, 1999). Whiteley (2000) has shown that, despite the fact that technology facilitating improved business practice in terms of developing electronic markets, electronic data interchange and Internet commerce, a number of small businesses have not capitalized on this new mode of carrying out business. Thus, the EM adoption is mainly due to the environmental micro and macro factors that are discussed above and the levels of EM implementation are shown below which is adapted from the Watson, et al (as cited by El-Gohary, 2008) (Figure 1).

According to him, there are five levels for EM implementation:

Therefore, EM is the gateway to global business and markets. EM adoption and implementation ranges from simply using e-mail to communicate within the organization to develop entirely new business models. To account for this range of adoption and implementation behavior, technology adoption and implementation can be defined as the breadth and depth of EB usage in a firm's business process.

EM implementation affects traditional marketing in two ways. First, it increases efficiency and effectiveness in traditional marketing functions. Second, the technology of EM transforms many marketing strategies. The transformation results in new business models that add customer value and/or increase company profitability (Strauss, et al, 2006). There are four levels of commitment to EB from activity level to pure play level as shown in Figure 2.

The activity level includes: order processing, online purchasing, e-mail, content publisher, business intelligence, online advertising, online sales promotions, and dynamic pricing strategies online. These activities focus on the efficiency of the organization which is cost reduction. While the business process level include: customer relationship management, knowledge management, supply chain management, community building online, database marketing, enterprise resource planning, and mass customization and these activities focus on the effectiveness of the organization which is customer retention or customer philosophy of the organization. Enterprise level and pure play level focus on the business transformation of the organization which is competitive advantage and industry redefinition.

Figure 2. Level of EM Commitment

In general, according to Strauss, et al (2006), EM implementation within the organization increases benefits (such as online mass customization, personalization that is giving stakeholders relevant information, 24/7 convenience, self-service ordering and tracking, and one-stop shopping), decreases costs (such as low-cost distribution of communication messages, low cost distribution channel for digital products, lowers costs for transaction processing , lowers costs for knowledge acquisition, creates efficiencies in supply chain, and decreases the cost of customer service), and increases revenue (such as online transaction revenues via subscription sales, or commission/fee on a transaction or referral; add value to products/services and increase prices; increase customer base by reaching new markets, and build customer relationships and thus increase current customer spending). The implementation of EB technologies is believed to impact myriad outcomes (Rapp, et al, 2008). The three major consequences of EM adoption and implementation are Marketing efficiency, Marketing effectiveness and Marketing performance.

The efficiency of marketing has been an important area of study in marketing performance assessment. Efficiency represents the comparison of outputs from marketing to inputs of marketing, with the goal of maximizing the former relative to the later (Bonoma and Clark, 1988). Sometimes called marketing productivity; and efficiency approach examines how best to allocate marketing activities and assets to produce the most output. Walker and Ruekert (1987, P. 19) defined efficiency as “the amount of effort relative to outcome of a business programs in relation to the resources employed” suggesting Return On Investment (ROI) as a measure. Bonoma and Clark (1988) defined efficiency as the amount of effort relative to the results, but particularly stressed the 'fit' of marketing programs with the company's existing marketing structures. Most simply, Drucker (1974, P. 45) referred to efficiency as “doing things right.” Virtually all early research in marketing performance assessment has drawn up on the efficiency approach, measuring out puts relative to inputs (Clark, 2000). According to Zhu, et al (2004), efficiency refers to increasing employee productivity, by reducing or streamlining internal processes.

The benefits sought by marketers in using EM include improved efficiency and lower costs across supply and demand chains; improved speed, flexibility, and responsiveness in meeting customer needs; greater market access; and enhanced ability to overcome time and distance barriers of global markets (Kotler, 2000; Quelch and Klein, 1996). In general EM can create efficiencies by reducing coordination costs for both buyers and suppliers. Efficiency enhancements can be realized by removing barriers to information flow via connecting previously unconnected parties and reducing information asymmetries through the availability of more accurate and timely information (Rapp, et al, 2008). The added availability of information can, in turn, reduce future sales transaction times, allow for more reliable and responsive decision-making, and reduce the likelihood of mistakes (Amit and Zott, 2001; Zhu, et al, 2004; Zott ,et al, 2000). Thus, the researcher proposed the proposition of:

P3: EM implementation by MLEs has a positive significant impact on the firms' marketing efficiency.

The competitive environment of modern day business appears to necessitate the successful implementation of EM, if a firm is to advance in its chosen market segments. Over the last few years, the concept of marketing effectiveness has attracted increased attention among academic researchers and business practitioners (Norburn, et al, 1990; Lai, et al, 1992; Ghosh, et al, 1993; Dunn, et al, 1994). The idea behind effectiveness is that any measure of performance should incorporate the objectives of the decision maker. In the organizational management literature, this is referred to as a goal-attainment view of organizational effectiveness (Lewin and Minton, 1986). Walker and Ruekert (1987) defined effectiveness as success versus competitors, which is certainly a common goal framework in marketing management. Drucker (1974, P. 45) described effectiveness as “doing the right thing,” while according to Clark (2000, P. 7) effectiveness is defined as “the psychological distance between what was expected to result from a marketing program and results as returned.”

A business that adopts a relationship marketing orientation will improve its marketing performance (Sin, et al, 2002). This implies that the marketing manger should give attention for the customer philosophy so as to improve the marketing profitability. In connection to this, Porter (2001) argued that Internet is the most powerful tool available today for enhancing operational effectiveness. By easing and speeding the exchange of real-time information, it enables improvements throughout the entire value chain, across almost every company and industry. He also further contend that the Internet help the organization to achieve sustainable competitive advantage by operating at a lower cost and by strategic positioning (doing things differently from competitors, in a way that delivers a unique type of value to customers). According to Kotler (1977), the marketing effectiveness of a firm entails an amalgam of five components: customer philosophy; integrated marketing organization; adequate marketing information; strategic orientation; and operational efficiency.

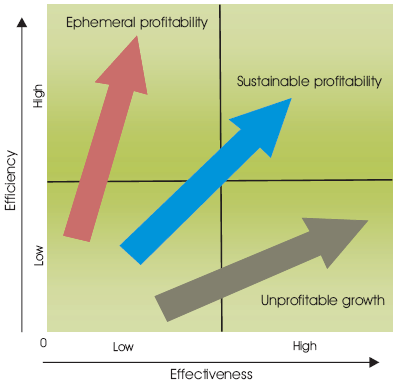

Figure 3. Efficiency versus Effectiveness trade-off

The researcher, thus, argues that a marketing success is often measured by marketing effectiveness, such as whether objectives are accomplished or not, but it can also be expressed in terms of achieving certain results. To achieve the objectives of the marketing programs, the adoption and implementation of EM is not only necessary but also mandatory in the globalized marketing environment. EM is a valuable strategy to generate customer retention and loyalty, acquisition, channel migration, sales goal achievement, customer education and market research. Moreover, the implementation of EM will increase the firm's effectiveness through the improvement of: customer relationship management (retaining and growing business and individual customers), knowledge management (a combination of a firm's database contents, the technology used to create the system, and the transformation of data in to useful information and knowledge), mass customization, community building, supply chain management (coordination of the distribution channel to deliver products more effectively and efficiently to customers), data base marketing (collecting, analyzing and disseminating electronic information about customers, prospects and products to increase profits), and affiliate programs. Through the improvement of these processes the marketing goals and programs will be achieved effectively. Thus, the researcher expects that:

P4: EM implementation by MLEs has a positive significant impact on the firms' marketing effectiveness.

Marketing performance measurement continues to be a large and growing concern for marketing scholars and managers alike (O'Sullivan, et al, 2009). No matter what condition an organization may be in, assessing marketing performance finds marketing management's day-to-day energies mostly devoted to matters of efficiency (doing things right) and effectiveness (doing the right thing) (Connor and Tynan, 1999). An organization's marketing performance success depend more on effectiveness and efficiency, however, the starting point should be measurement of marketing effectiveness, for doing the wrong things efficiently is pointless.

Efficiency is not a measure of success in the market place. It is rather a measure of operational excellence or productivity. It is therefore, concerning with minimizing costs and improving operational margins. On the other hand, effectiveness is linked to a company's ability to design a unique model of embracing business opportunities through exchange relationships. Effectiveness is, therefore, related to the company's own recipe to generate a sustainable growth in its surrounding business network. Gaertner and Ramnarayan (1983) argue that effectiveness is not a characteristic of organizational out puts but rather a continuous process relating the organization to its constituencies; it is negotiated and rather than produced. An effective organization is one that is able to create accounts of itself and of its activities that relevant constituencies find acceptable. The accounts may be for various purposes to various audiences and for various activities.

Figure 3 shows that focusing on efficiency and neglecting effectiveness would result in an ephemeral profitability. In contrast, focusing on effectiveness and neglecting efficiency may result in an unprofitable growth. Thus, a balanced approach that aims at high efficiency and high effectiveness would require for the success of organizations and this would make organizations to “stretch” their endeavors. Effectiveness may be seen as a long term while efficiency may be seen as a short-term achievement. For instance, sales or business managers who are responsible for a particular segment of a business may act within a long-term horizon of growing their sales volume. Similarly, marketing managers responsible for a number of products appear to act within a long-term horizon of building advertising awareness and market share. When we come to efficiency, it appears that managers are primarily concerned with short-term cost cutting to meet quarterly profits and operating cash flow. The applications of information technology on the traditional marketing activities (which is called EM) are the major vehicle to increase the marketing efficiency and effectiveness within organizations.

The researcher believes that to be successful in the competitive and globalized marketing environment, marketing management must be effective in working with other departments and earning their respect and cooperation. Moreover, the key managers should recognize the primacy of studying the market, distinguishing the many opportunities, selecting the best parts of the market to serve and gearing up to offer superior values to the chosen customers in terms of their needs and wants. Moreover, the organization must reflect a well-defined system for developing, evaluating, testing and launching new products because they constitute the heart of the business's future. In today's market, effective marketing calls the executives to have adequate information for planning and allocating resources properly to different markets, products, territories, and marketing tools and should have a core strategy that is clear, innovative and databased. However, not all these marketing programs and plans bear fruit unless they are efficiently carried out at various levels of the organization. Thus, marketing managers should maintain optimal levels of efficiency and effectiveness that will lead the sustainable profitability and growth of the organization; and all these call the adoption and implementation of EM, which affects directly and /or indirectly the marketing efficiency, effectiveness and performance within the organization. Therefore, the researcher could propose as:

P5: There is a significant positive relationship between marketing efficiency, effectiveness and the firm's marketing performance.

P6: There is a positive significant relationship between e-marketing implementation and the firms' marketing performance.

Figure 4. Conceptual Model

The objective of this research is theory construction rather than theory testing to create a theoretical link between EM adoption and implementation and the consequences it has over the marketing efficiencies, effectiveness and performance. Accordingly, attempts have been made to identify the variables that encourage or impede the adoption and implementation of EM within the medium and large business enterprises in Ethiopia. More specifically, the researcher has identified two important classes of variables that affect the adoption and implementation of EM within the Ethiopian Medium and Large business organizations with the effect EM has on the business organizations' marketing efficiency, effectiveness and performance (Figure 4). The propositional inventory and the integrated framework represent effort to build a foundation for the systematic development of a theory of EM implementation and effect on the business' marketing efficiency, effectiveness and performance.

Having these levels of impact it has over the marketing performance of the medium and large business enterprises in developing countries a case of Ethiopia, the research propositions have a direct managerial implications. First, the research clearly delineates the factors that can be expected to foster or discourage EM adoption and implantation within the Ethiopian Medium and Large Business enterprises. The majority of these identified variables is controllable by managers and therefore can be altered by them to improve the marketing performance of their organizations. Second, it gives managers a comprehensive view of what EM is and the factors to attain it; and finally, the likely consequences it has over the Ethiopian Medium and Large Business Organizations. Managers and practitioners therefore should give due attention for the development of EM strategies while running their business enterprises in the competitive marketing environment. Over the last decade, interest in EB and EM have evolved from optimistic scenarios with the explicit message that “if you are not an EB, you are out of business” just to give emphasize on the values of EB over the durational ones.

Attempts have been made to identify the factors that foster or impede for the adoption and implementation of EM and the consequences it has over the marketing efficiency, effectiveness and performance. However, a great job has remained uncover just to develop a suitable measures of EM adoption and implantation, marketing efficiency and effectiveness measures as well as marketing performance measures to empirically test the propositions in the study. Thus, future researchers are encouraged to develop such measures and take empirical tests to prove the theoretical framework constructed understudy.