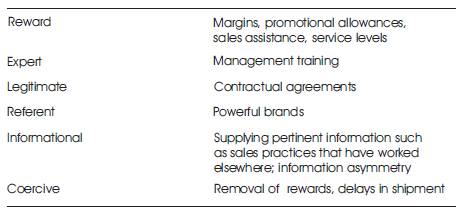

Table 1 Sources of Power Examples

Popular press is replete with articles suggesting that one of the major reasons for the collapse of several manufacturing organizations is their lack in executing relational exchanges with their business partners such as their distributors. These firms are constantly falling a prey to dysfunctional micromanagement techniques, which facilitate quick sales growth, but, never-the-less, at the expense of ultimate damage to the firm. The basic premise is that these manufacturers have not accepted the belief that buried in these set of relational exchanges are the sociopolitical processes of sources of power, dependence, and conflict, whose interplay need to be understood from both parties' perspective. These manufacturers eventually become insensitive to market demand by maintaining their inflexible, silo mentality and repudiating the idea of balancing these internal sociopolitical processes towards an enduring, committed relationship. Using distributor literature, a case study, and an Insider Accounts approach to survey a foreign equipment manufacturer and three of its U.S. distributors, from the manufacturer's perspective, high dependency resulted in low manufacture's conflict. High distributor's non-coercive power led to low manufacturer's conflict. High coercive power was positively associated with manufacturer's conflict. From the distributor's perspective these associations were reversed. Managerial implications are suggested.

Manufacturer-Distributor (M-D) exchanges are envisioned as inter-organizational systems with the goal of making goods and services available for consumption. A major focus of each focal dyad within these exchanges is to develop an appropriate organizational structure and process. A current school of thought is to rely on the governing mechanism of relational exchanges such as flexibility, information sharing, and trust to manage a dyadic exchange. These elements of relationship quality are presumed to sustain the relationship (Palmatier, Dant, & Grewal, 2007). However, obscured in these governing mechanisms are the sociopolitical processes of power, dependence, and conflict whose interplay need to be understood for enhancing channel performance (Stern & Reve, 1980). For example, Weitz and Jap (1995) classify relational exchanges as authoritative, normative, and contractual methods of control and claim that operating within each of these control categories are coercive and non-coercive sources of power. Furthermore, they caution that the misuse of power may generate conflict and dampen the development of such relationships. Thus, it is not surprising that power, dependence, and conflict are resurfacing in the supply chain and distribution channel literature.

Channel theorists agree that an exchange may be coordinated not only through relational governing mechanisms but also by other means such as administrative procedures, contractual agreements, or through influence by sheer power (Heide, 1994). Proper usage of power is considered a relational norm element. An unbalanced power structure is a reason for the coexistence of multiple governance mechanisms (Bandyopadhyay & Robicheaux, 1997). Moreover, popular press is replete with articles stating that a major reason for the collapse of several manufacturers is their lack in executing proper relationship management techniques; that is, such firms are constantly falling a prey to destructive micromanagement techniques, which facilitate quick sales growth, but, never-the-less, at the expense of ultimate damage to the firm. These firms have not clearly understood internal sociopolitical phenomenon of how to manage power, conflict, and dependence from a dyadic perspective. They eventually become insensitive to market demand by maintaining their inflexible, silo mentality and not delegating authority to their channel members. They are failing to heed the warnings of discontent theorists (e.g., relative deprivation, reciprocal action, and reactance theorists) that manufacturers are focusing only on the immediate advantages in using a distributor's expertise rather than understanding the discontentment caused by the misuse of authority (Frazier & Rody, 1991; Zoogah, 2010). The power-dependence relationship is being exploited in the M-D exchange, which is resulting in flawed information transfer, high levels of conflict, and inferior quality of goods and services being developed and sold (e.g., Frazier & Rody,1991;Mangin, Valenciano,Koplyay, 2009)

Although channel theorists have suggested the possibility of the relationships between these sociopolitical constructs to move in opposing directions, depending on whose perspective is taken, actual data has not been simultaneously collected from both parties to realize the potential of such research (Gaski, 1984; Frazier & Rody, 1997; Dickson & Zhang, 2004). Such manufacturers and their distributors enter into long-term relationships because of the nature of the product being sold and the intensity of the after-sales services required. Therefore, the associations between the internal political processes need to be understood from a dyadic, enduring relationship perspective rather than short-term, authoritative perspective ensuing from the manufacturer alone.

The purpose of this study is to investigate power, dependence, and channel conflict relationships between a large Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) operating in the U.S. market and three of its distributors from a dyadic perspective. Using a case study and an Insider Accounts approach (Ekanem, 2007) discussed later, the major sources of power, dependence, and conflict are measured in a pilot survey administered simultaneously to both this multinational OEM and their distributors A, B, and C. The distribution literature and findings serve as the basis for an agenda of testable propositions from a dyadic perspective. Once this internal sociopolitical phenomenon is understood and accepted, both the manufacturer and its distributor may jointly specify roles and obligations of each channel member and adjust their dependencies and sources of power to reduce conflict and improve channel performance. The paper is organized as follows. First, the M-D relationships in terms of the internal sociopolitical phenomenon are briefly explored from a theoretical and empirical perspective. Next, the sociopolitical constructs of conflict, power and dependence are discussed within the context of this industrial setting study. Then, the methodology and the results are explained. Based on these findings a set of four propositions is presented. Lastly, implications from this study are discussed.

Despite years of relationship research, M-D relationships are still fraught with problems and misunderstandings. Some manufacturers have pulled back from continuing such relationships due to inadequate distributor performance (Pressey & Qiu, 2007). A major reason for this relationship dissolution is the lack of both the manufacture and its distributor to understand and accept each other's viewpoint about their internal sociopolitical processes. Relative deprivation, reactance, and reciprocal action theorists state that the weaker party to the exchange, generally the distributor, feels discontented by the manufacturer's misuse of authority as the M-D pair strives to accomplish personal objectives and mutual goals. The distributor redresses the perceived exchange inequity using its resources (Zoogah, 2010). A manufacturer and its distributor will attempt to respond to each other's coercive and/or non-coercive sources of power on a one to one basis, which may deteriorate the relationship (Frazier & Rody, 1991). This problem then leaves the manufacturer with an option to find a replacement, and even if it does, the issue may persist. Moreover, retaining and improving current relationships is generally more cost efficient than establishing new ones, considering it is difficult to find new distributors (Kalwani & Narayandas, 1995)

In the M-D exchange, the distributor overcomes entry barriers to the market and develops and maintains a market for the manufacturer. However, this distributor also represents several non-competitive manufacturers and thus needs to pursue its self-interest and personal goals. The equipment manufacturer, on the contrary, may need the distributor to concentrate its energies in certain distribution functions such as parts and inventory and specific markets. From the distributor's perspective this method of allocating its resources may not be the best way to achieve its economies of scale, which may generate channel conflict. The manufacturer may then misuse its sources of power to reduce its conflict. This chain reaction and the nature of dependency that exists between the M-D partners create a discontented state. The distributor perceives a discrepancy between the way it was optimizing its business activities versus the way it is being conditioned by the manufacture to practice it. The distributor seeks fairness in the exchange through other relationship techniques (Zoogah, 2010). These methods are described in distribution literature as distributor's countervailing power (Etgar, 1976) and offsetting dependence through bonding behavior with the client instead of the manufacturer (Heide & John, 1988).

Based on the discontent theories, the distributor is attempting to diminish these authoritative inequalities by improving its sources of power or reducing its dependence, which affects its own conflict in this exchange. Thus, the associations between the internal sociopolitical constructs may move in opposing directions depending on whether it is viewed from the manufacturer or the distributor's perspective. Empirical studies have also endorsed this view. For example, Srikonda (1999) reports that although several manufacturers believe that the relationships with their distributors are good, this belief is contrary to the responses gotten from their distributors. Trade magazines endorse this viewpoint by claiming that a large percentage of global outsourced deals are not renewed because of the differences in the governing styles of both parties. These differences lead the service provider to complain about unrealistic client expectations and the client to complain about poor service provider management practices (e.g., Industry Week, 2010).

Channel researchers have recognized that although the sources of power, conflict, and dependence play an important role in managing M-D relationships, a member can mar the relationship by applying it in the direction of dominating the channel rather than apportioning it in a wise, benevolent manner to promote healthy relationships. For example, Lusch and Ross (1985) in their study found wholesalers and brokers to disagree (conflict) over the importance given to the different distribution functions provided by their respective organizations. In addition, sources of power for each party were limited in scope and dependent on the distribution activity under consideration. Their results also suggest that the wholesaler and its broker each amassed power over different distribution activities through self-selection rather than any planned allocation of these activities. By not coming in each other's way was assumed to provide the check and balances of power mismanagement. They concluded that this disorganized way of allocating control over distribution activities may produce a negative outcome. Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp (1995), in their study, point out that dependence asymmetry between the manufacturer and its dealer (relative dependence) resulted in greater distributor conflict; however, total overall dependence between the parties exhibited lower overall conflict.

Furthermore, some researchers have found that a firm's dependence on its partner to increase conflict between them and also the exercise of coercive power from its partner (e.g., Brown, Lusch & Muehling,1983; Frazier, Gill,& Kale,1989) whereas others have found the relationship to be the opposite (Frazier & Rody, 1991). Recently, researchers have suggested that the reason for the mixed findings between the sociopolitical constructs may be that firms are querying both parties relative and overall dependence from one party's perspective (e.g., Anderson & Narus, 1990; Heide, 1994; Mangin et al.,2009). Thus, there is a clear need to understand marketing channels from a dyadic perspective and simultaneously querying each channel member about its respective perceptions of channel behaviors.

Channel conflict is deemed inevitable between channel members (Brown et al., 1983). This potential state of conflict exists because the manufacturer and its distributor perform specialized activities that create functional interdependence between them. Sometimes the activities need to be performed in a sequence. The distributor needs to process the order before the manufacturer can ship the product. Occasionally, two activities need to be performed in synchronism by both the manufacture and its distributor. For example, a new equipment may have some options a customer may not necessarily desire but may be willing to purchase if a price discount can be offered by the manufacturer. For example, the manufacturer and its distributor may require timely coordination and cooperation to complete this sale. Since the manufacturer and its distributor are independent firms, this forced functional dependence will be in constant clash with their desire to be autonomous, generating conflict (Sachdev, Bello, & Verhage, 1995). Therefore, these firms must deal with conflicting issues in a positive light rather than allow them to gradually seep through the system and eventually pull down the parties into dysfunctional exchanges (Brown, Cobb, & Lusch, 2006). In order to understand this phenomenon, practitioners must understand the underlying reasons for conflict and the way they are measured. Moreover, since channel partner's dependence on each other is asymmetric, the outcome of such relations, if not understood and acted upon, becomes dysfunctional ( Stern & Reve, 1980; Kumar et al., 1995). Proper checks and balances are needed to curtail such results.

Although researchers have defined channel conflict in various ways, the consensus is that negative sentiments are felt by one channel member that its goals are being impeded by the other channel member (Gaski, 1984). Based on this definition conflict is treated as dysfunctional behavior in this study. Additionally, since we are studying conflict from both the manufacturer and distributor's perspective, conflict is only perceived and may not necessarily be manifested. This is because, as discussed later, one person's acknowledgement of conflict may not be considered as an issue for the other (e.g. Kumar et al., 1995).

Manufacturers and their distributors are interdependent on activities ranging from manufacturing the product to completing the sales and providing after sales support, which makes dependence a crucial construct in marketing channels (Kumar et al., 1995). A manufacturer's dependence on its distributor and vice versa is positively related to the portion of the manufacturer's goals performed by the distributor and the distributor's goals performed by the manufacturer (Emerson, 1962). The manufacturer's goals are different from its distributor's goals. For instance, a manufacturer is dependent on several distributors to accomplish its goals, and the distributor is dependent on its territory and other manufacturers to accomplish its goals. Additionally, dependence is also related to the cost and alternatives available to replace its partner if the need arises. These replaceability reasons are different for each party (Anderson & Narus, 1990).

Power is the ability of one party to influence the decisionmaking of the other party (Hunt, Mentzer, & Danes, 1987). The ability of a manufacturer to control his distributor and vice versa depends on each party's sources of power (Gaski, 1984). These sources of power consist of six different types namely, reward, referent, legitimate, expert, informational, and coercive (Table1). Furthermore, these sources have been dichotomized into noncoercive (reward, expert, legitimate, and referent) and coercive sources of power (Gaski, 1984). “This dichotomy has been employed because of the difficulty involved in differentiating the various non-coercive sources of power” (Richardson & Robicheaux, 1992, p. 244).

Table 1 Sources of Power Examples

The methodology for this study was a combination of a case study and Insider Accounts. This aspect of qualitative research consists of a longitudinal case study where the researcher probes sensitive social science behavioral issues through in-depth interview methods to suggest testable propositions (Ekanem, 2007). This methodology is appropriate when little is known about the phenomenon and, consequently, one cannot rely heavily on past literature. It is also a useful strategy for exploratory investigation of a phenomenon where the researcher works on semi-structured interviews with a handful of participants and sensitive information needs to be revealed by the parties involved (Yin, 2003; Balmer & Liao, 2007).

This study deals with a foreign equipment manufacturer (world-wide sales of $20 billion and U.S. sales of $4 billion U.S. dollars in 2008) and three of its U.S. distributors, A, B, and C (annual individual sales between $100 - $150 million in U.S. dollars). These equipment distributors sell, rent, and lease a wide variety of machinery. They also provide complete product support once the equipment is leased or sold. These distributors are independently owned local businesses that contract with manufacturers to serve customers in a specific geographic territory. They do not sell competing manufacturers' products. Moreover, they have exclusive contractual agreements with the manufacturer to sell in a territory, which generally spans over an entire state.

First, the manufacturer's VP Sales was contacted and a personal interview was conducted. The face-to-face interview resulted in understanding the nature of the firm's distribution practices and relationship issues with its distributors. Permission was granted to speak with the General Manager, the Distribution Manager of this manufacturer, and the owners of three of its distributors, A, B, and C. Distributor A was a local distributor. Distributor B's co-owner was visiting the manufacturer during the time frame of this study for other business reasons, and distributor C agreed to participate via phone interviews. In addition, the manufacturer's local trade association agreed to provide input in developing the questionnaire. The three distributors A, B, and C, varied in their relationship effectiveness with this equipment manufacturer. The equipment manufacturer's relationship with distributor A was the best and with the other two B and C was mediocre. The quality of this relationship was judged based on the interview with the manufacturer. Interviews were conducted over four stages and over a period of six months. The process of going though these stages enabled both the researcher and participants to build rapport and credibility with each other, to understand the practitioner and academic literature and the data to be gathered, and to finalize the questionnaire (Appendix A).

In this study, sources of power was measured as a possession of power rather than its execution, which are two different sub constructs of power (Gaski, 1984). The items were adapted from Swasy's (1979) study on power measurement, who developed this instrument as follows: The questionnaire on referent, expert, legitimate, information, reward, and coercive power was administered to 300 college students. Next, the validities and reliabilities were calculated. The only item with a low alpha was for legitimate power (0.38), “Because of the manufacturer's position, they have the right to influence me.” The non-coercive power was calculated as an overall index of referent, expert, reward, and legitimate power.

Conflict has been measured in several ways. Lusch (1976) gauged conflict as the frequency of disagreement between manufacturers and distributors across twenty issues. Etgar (1979) assessed conflict through the frequency and intensity of disagreement. Thomas (1976) suggested measuring only the important conflict issues in an exchange since the parties may not be concerned if the issues were unimportant. Finally, Brown and Day (1981) combined the studies of various researchers and concluded that Importance (I), Intensity (N), and Frequency (F) were essential in measuring channel conflict. They studied fifteen conflicting distribution issues and found that the summation of the multiplicative term of I*N*F to be the best measure of conflict.

Past researchers (e.g., Frazier & Rody, 1991) have mainly examined conflict from either the manufacturer or distributor's perspective. In this study, both the manufacturer and distributor's points of view were addressed across 40 issues of conflict. None of these issues could be considered unimportant, because if some issues were unimportant to the manufacturer, they were considered important to the distributor. The importance of the issues also varied by the distributor involved. For example, advertising was important in the relation between the equipment manufacturer and distributor A but was considered unimportant in the relation between manufacturer and distributor B. Based on these factors the overall index of conflict was formed by multiplying across each item and summing over the items.

The commonly held view of dependency is based on Emerson's (1962) proposition, “The dependency of actor P over actor O is 1) directly proportional to P's motivational investment in goals mediated by O, and 2) inversely proportional to the availability of those goals to P outside the O-P relation” (p. 32). In this study, dependency was measured by the scale developed by El-Ansary (1975), who utilized Emerson's (1962) proposition and adjusted it to marketing channels. In that study, the three factors emerged were stake (sales volume and profit), cost of alternatives, and number of alternatives available. This scale has also been used by other researchers (e.g., Heide, 1994).

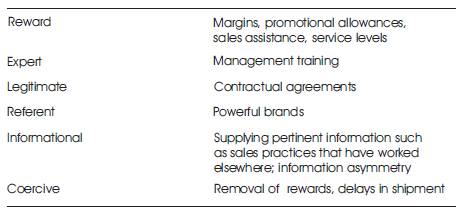

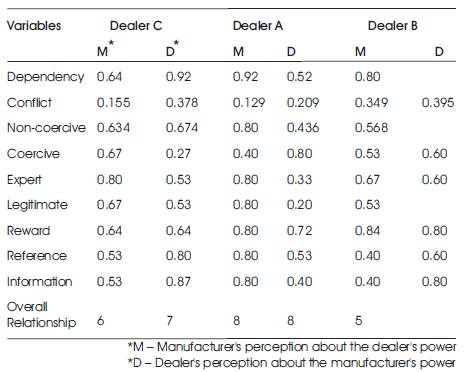

Because of the small sample size, the individual items of each of the power, dependency, and conflict were summated across their total items and an index formed for each construct. For example, if a distributor scored 2500 across total conflict items and the maximum possible score was 5000 then the conflict index would be 2500/5000 = 0.5. The results for each of the sources of power, total non-coercive source of power, dependency, and conflict are shown in Table 2. This table indicates that the manufacturer's perception of conflict is always lesser than the distributor's perception of conflict. As the overall relationship with the distributor declines, the conflict level increases. Moreover, as discussed below, the relationships between the sources of power and conflict, and dependency and conflict move in the opposite direction when observed from the manufacturer rather than distributor's standpoint.

Table 2. Results

Based on the results, predictive validity of the data was addressed by measuring two underlying, acceptable associations. First, as accepted in literature, in this study the sources of power and dependence were positively associated from both the manufacturer and distributor's perspective. The manufacture perceived distributor A, B, and C's coercive power as 0.8, 0.634, and 0,568 and dependence on them as 0.92, 0.64, and 0.80, respectively. Comparing manufacturer's assessment of distributor A and C and distributor A and B indicate dependence and non-coercive power to be positively related. Similar results were obtained from the distributor's perspective. Dependence and coercive power scores are negatively related from both the manufacture and distributor's perspective.

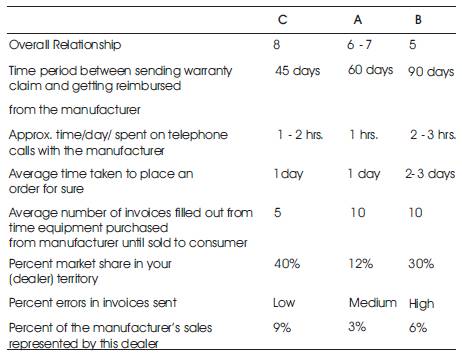

Secondly, in this study performance data were gathered with respect to distributor's task effectiveness (Table 3). Based on this performance metrics, distributor A was the most accomplished, and the manufacturer had the least conflict with this distributor. Distributor B was the least effective, and the manufacturer's perceived conflict with this distributor was the highest thus showing a negative relationship between conflict and performance (e.g., Dickson & Zhang, 2004).

Table 3. Performance

The manufacturer's overall relationship with Distributor A was good (8 on a 10 point scale); the level of conflict perceived by the manufacturer was 0.129, and the level of conflict perceived by distributor A was 0.2086. In the case of distributor B, the overall relationship was five. The level of conflict perceived by the manufacturer was 0.349, and the level of conflict perceived by the distributor was 0.395. The table is self-explanatory. The manufacturer is more dependent on distributor A (0.92) than distributor B (0.80). Thus, from the manufacturer's perspective, one may derive the following proposition:

P1: As manufacturer's dependency increases, its conflict level with the distributor decreases.

From the distributor's perspective, distributor A consider itself to be less dependent (0.52) on the manufacturer than distributor C (0.92), whereas, the level of conflict was more in the case of C (0.378) than in the case of distributor A (0.2086). Thus, from the distributors' standpoint one may postulate:

P2: As distributor's dependency increases, its conflict level with the manufacturer increases.

From the manufacturer's point of view, distributor A has more non-coercive power (0.8) than either distributor B (0.568) or distributor C (0.634). The corresponding manufacturer's conflict scores are 0.129 with A and 0.349 with B, and 0.155 with C, respectively. It is difficult to compare distributor B and C, because the overall relationship rating is quite close, 5 and 6, respectively. Thus, the following proposition may be postulated.

P3: From the manufacturer's perspective, there is a negative association between distributor's non-coercive power and manufacturer's conflict.

On the contrary, distributor A considers the manufacturer to possess less non-coercive power (0.436) than distributor C perceives the manufacturer to possess (0.674). Distributor C at the same time has more conflict with the manufacturer (0.378) than distributor A has with the manufacturer (0.209).

P4: From the distributor's perspective, there is a positive association between the manufacturer's possession of non-coercive power and distributor's conflict.

For the coercive sources of power, the results did not indicate a clear direction except for the distributor A and C case. The manufacture's perceptions of high distributor 's coercive power resulted in high manufacturer's conflict; however, from the distributor's perspective, high manufacturer's coercive power resulted in low distributor's conflict.

Manufacturers are expending more time in learning short hand techniques in becoming powerful player in today's global economy at the expense of relationship endurance or channel performance (Fortune, 2010). However, a manufacture-distributor relationship is not without its interdependency. This dependency sows the seeds for conflict, power, and other behavioral relationships (Stern, El-Ansary, & Coughlan, 1997). Both the manufacture and its distributor need to understand the interplay between these constructs from a functionality perspective, recognizing that these sociopolitical dimensions will always be present in their overt or covert form. Moreover, discontent theorists suggest that both parties have expectations about each other's sociopolitical behavior. The manufacturer expects its distributor to be concerned about the manufacturer's welfare in a territory unfamiliar to the manufacturer (Frazier et al., 1989; Palmatier et al., 2007). Because of this dependence, the manufacturer will be cautious in sustaining conflict at a low level for fear that the distributor may retaliate and hamper the manufacture's sales. The distributor expects the manufacturer to allow it to participate in the same distribution functions over time but may fear being bypassed once it has built a territory for the manufacturer and may engage in hostile behavior against the manufacturer if its dependency increases (Lawler, Ford, & Blegen, 1988).

After surveying a foreign equipment manufacturer and three of its U.S. distributors, a few important behavioral M-D issues emerge. The interrelationship between the construct of dependency and conflict and power and conflict had opposing effects on each other when viewed from the manufacturer and the distributor's perspective, respectively. From the manufacturer's perspective, high dependency resulted in less channel conflict. From the distributor's perspective high dependency induced high conflict. Non-coercive sources of power possessed by the distributor led to low levels of conflict perceived by the manufacturer whereas greater coercive power resulted in higher conflict. From the distributor's perspective, these associations were reversed. One of the reasons may be that the distributor is specifically selected for its expertise, superior market information, and ability to build a territory to reward the manufacturer. The distributor selects the manufacturer for profitability reasons rather than a provider of information and expertise of the market place. Thus, mismanaged non-coercive sources may not always result in compliance. Considering the small sample size, the strength of this study is not in the directions of the individual relationships between the sociopolitical processes as much as it is pertaining to the opposing viewpoints when studied from a dyadic perspective.

The results strengthen Gaski's (1984) suggestion that in a channel dyad, one entity's perception about the other party's power and channel conflict will be inversely related to the other entity's perception. Failure to recognize this phenomenon may create a scenario where a party may perceive that certain sources of power techniques resolve its conflict with a distribution activity but the effect may only be temporary. For example, due to exchange rate fluctuations the manufacture may avail its sources of power to adjust its profit margins. The distributor may offset this loss by overstating its service claims with a customer that may not be traced by the manufacturer due to information asymmetry reasons. This shortsightedness may result in the ultimate demise of the M-D relationship as has been observed by relationship analysts given the recent spate of bankruptcies of large corporations (Automotive News, 2010). Rather than use countervailing power to prevent the other party's power from becoming pervasive or increase the other party's dependence through offsetting techniques, the division of power and dependence should be crafted in the direction of continuous M-D relationship improvement.

This study focused on M-D relations pertaining to a product that required a strong commitment to service after sales; other M-D exchanges may have some other product attributes that may be of prime importance. In addition, environmental issues (uncertainty, competition, etc.), which have not been discussed in this study, may also have a bearing on channel conflict (Achrol & Stern, 1988). A manufacturer may also become dependent on its distributor because of the need to share proprietary information in the exchange, which can create an extreme imbalance of power. Thus, the specific reasons for dependence at the activity level may need to be explored and addressed (Heide & John, 1988; Mangin et al., 2009). For example, if market share versus profitability focus were a conflicting issue then a reasonable solution to this problem would be for the manufacturer to reimburse the distributor portion of its profits for supporting the market share principle.

For each of the following statements, circle whether you strongly disagree (2), don't know (3), somewhat agree (4), or strongly agree (5).

If we do not comply with the dealer, we will not be rewarded.

The only reason for doing as the dealer suggests is to obtain good things in return.

We want to do as the dealer suggests only because of the good things the dealer will give us for complying.

The dealer has the ability to reward us to some manner if we do as they suggest.

If we do not do as the dealer suggests, we will not receive good things from them.

In general, the dealer's opinion and values are all similar to ours.

Being similar to our dealer is good.

We want to be similar to our dealer.

The information provided by the dealer about most situations makes sense.

The information provided to us by our dealer is logical.

We do seriously consider the dealer's requests because it is based on good reasoning.

The dealer will harm us in some manner if we do not do as they suggest.

If we do not do as our dealer suggests, he will punish us.

Something bad will happen to us if we do not do as the dealer requests and if they find out.

We mostly trust the dealer's judgment.

Our dealer's expertise makes them more likely to be right.

The dealer has a lot of experience and usually knows best.

It is our duty to comply with the dealer.

Because of the dealer's position, they have the right to influence our behavior.

We are obligated to do as the dealer suggests.

This dealer will be hard to replace.

Discontinuing the relationship with this dealer will affect our firm's profit negatively.

We are very dependent on the services of this dealer.

There are an extremely few alternative dealers available for the kind of business we are in.c

The cost (money, time, effort) involved to switching to an alternate source will be tremendous.

On a scale of 1 through 5, please rate the following variables/statements on (i) importance of its affecting manufacturer-dealer relationships (5 – very important), (ii) frequency of disagreement (5-very frequent), (iii) intensity of disagreement (5-very intense).

Important Frequency Intense

Please state the facts and figures for this section. All questions pertain to the manufacturer – dealer section of the transaction unless stated otherwise.