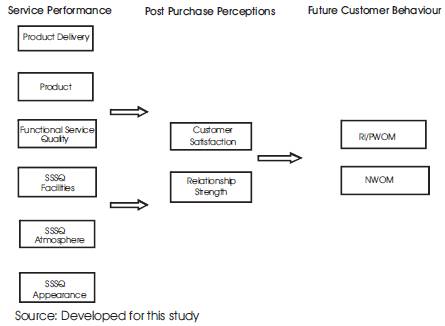

Figure 1. Original theoretical illustrated model (Model 1)

There has been extensive research conducted in the area of service quality and the factors that encourage customers to repurchase a product. In some service settings the servicescape can have a significant effect on what a customer experiences and the subsequent perceptions and behaviour of that customer. The material presented in this document has been extracted from a larger doctoral thesis research study of five hundred coffee shop patrons, which was undertaken to measure the effect of servicescape on consumer's perceptions of service quality, and further investigated the potential significance of the inclusion of the 'servicescape' in a model relating customer service quality with customer behavioural outcomes in a service setting.

The results contribute to marketing theory by empirically showing that the addition of the servicescape construct with other service quality constructs improves the prediction of customer post-purchase perceptions and behaviours with a parsimonious model identified.

However, and of greater significance in contributing to marketing theory, a more complete general service quality model relating customer service quality with post-purchase customer behaviours, the PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour, was developed combining a specific set of service quality constructs, which may be of value to researchers and practitioners alike in studying various service sector organisations.

The aim of this paper is to review how the service environment or 'servicescape' affects customer post purchase behaviour. Specifically, the research addressed the impact of servicescapes on customer perceptions of service quality. The research developed and tested a new theoretical framework, PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour. Therefore, PAWs model should provide service providers with a means of evaluating the relationship between the retail establishment and their consumers.

The service sector has grown to become one of the dominant drivers of economic growth (Bigné, Moliner & Sanchz 2003 and Brady, Cronin & Brand 2002). In countries such as Australia, India and the United States of America, the service industry is the fastest growing industry and the largest sectors. The Australian economy has 8.8 million (85 percent) of employed Australians in service industries and accounting for about three-quarters of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007 and Veldre 2007).

In India the services sector contributes significantly to the countries Gross Domestic Product (GDP), accounting for 56 percent during 2008-09 and according to Ranjeet S. Mudholkar, principal advisor of the Financial Planning Standards Board India (2009), 'with innumerable surveys revealing the immense growth prospects in India and the country being projected as one of the high-growth economies in the world, there is an increasing realisation for the need of more professionals and experts in financial planning' (Mudholkar 2009).

In 1993 the services sector in the United States of America accounted for 66 percent of the Gross National Product (GNP), while 75 percent of all jobs resided in service industries, and 85 percent of all new jobs were created from service providers (Henkoff 1994; Rust & Oliver 1994; Shugan 1994 and Daniels 1993). Since that time the services sector continues to be the fastest growing sector in the USA accounting for 83 percent of the Gross National Product in 2006 (Howells & Barefoot 2007).

The importance of the services sector has resulted in intense competition between service providers (Brady, Cronin & Brand 2002). From an economic perspective, a service providers understanding of consumers evaluative processes contributes to their profitability and market performance from future customer behaviour (Zeithaml 2000; Rust & Zahorik 1993 and Koska 1990). From a social viewpoint, however, service providers have the opportunity to contribute to a consumer's well being as their service is likely to impact on a customer's quality of life (Sirgy 1996 and Sirgy & Lee 1996).

Service Quality (SQ) has become an increasingly indispensable aspect for service providers in managing a successful business operation in today's competitive service market (Blose, Tankersley & Flynn 2005 and Schneider, Holcombe & White 1997) with consumer's perceptions of the actual quality of the customer service delivered and received in relation to the product often influencing a service provider's service quality (Perrone 2009). Consumer reactions to SQ can result in a number of positive benefits, such as:

(Duncan & Elliot 2004; Ranaweera & Neely 2003; Jamal & Naser 2003; Alexander, Dimitriadis & Markata 2002; Yavas, Bilgin & Shemwell 1997; Buttle 1996; Kim & Kleiner 1996 and Zahorik & Rust 1992).

Since the 1970's service quality in the retail environment has provided marketers with a vast field of research. Kotler (1973) emphasised the importance of retail marketing strategies by focusing on the relevance of atmospherics in influencing consumer behaviour. Marketers have been subsequently exploring ways and means of producing a coherent framework for analysing retail environments (Gilboa & Rafaeli 2003).

'Servicescape', which refers to the physical surroundings in a service environment, was a term first introduced by Mary Jo Bitner (1992). The physical surroundings are important in service settings because customers are affected by these surroundings (Bitner 1992). This study addressed how the servicescape can influence the way consumers react to a product or service provider, and contributes to our understanding of consumer behaviour (d'Astous 2000). This study describes the theoretical foundation and the methodology proposed on the service environment and how that environment relates to subsequent customer perceptions and behaviours.

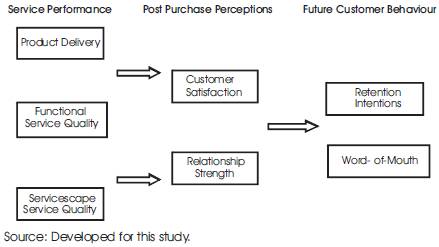

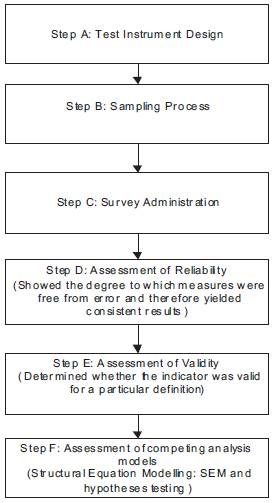

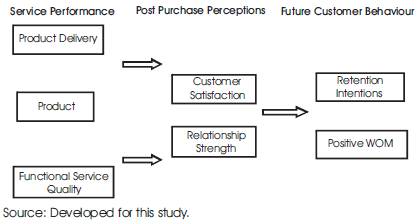

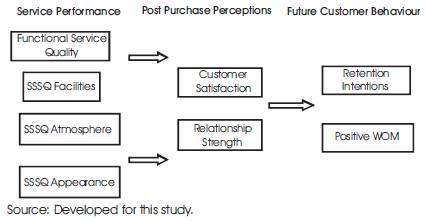

In order to measure how the environment relates to subsequent customer perceptions and behaviours, the proposed model has three types of variables: service performance, post purchase perceptions and future customer behaviour. The concepts of each variable are provided as follows:

Hence, this study investigated the retail service environment, which was empirically tested in coffee shops and provides for a wider understanding of consumers responses to environmental cues in the retail servicescape. There are numerous research papers on servicescapes however this study supports a model of service quality in which the servicescape is a fundamental part. The outcome of a review of the 'servicescape' literature and its possible impact on service quality, as perceived by customers, has identified a gap in existing service quality models.

The study addressed this gap by, developing and testing a new theoretical framework and, adding the construct servicescape service quality, to other service quality constructs, product delivery and functional service quality and their prediction of customer satisfaction, relationship strength, retention intentions and word-of-mouth. The origin of this theoretical framework can be traced to the seminal conceptualisation of service quality advanced by Grönroos (1990, 1982). Specifically, Grönroos' (1990, 1982) conceptualisation put forward that service quality is the result of customer perceptions of the interaction that takes place during customer service delivery (functional service quality) and product delivery (technical service quality), which is the outcome result of the production process.

When technical and functional service qualities are combined, as the literature suggests, the addition of other constructs such as the physical environment (servicescapes) plays a key factor in the development of service quality perceptions (Dann & Dann 2004; Schiffman & Kankuk 2000; Schiffman, Bednall, Watson, & Kanuk 1997; Zeithaml, Parasuraman, & Berry 1990; Grönroos 1988; Parasuraman, Zeithaml & Berry 1985; Zeithaml, Parasuraman, & Berry 1985; Lovelock 1983; Normann 1983 and Grönroos 1982).

This study therefore developed a framework detailing the relationship between service quality constructs and the servicescape in determining the predictive powers of future customer behaviour by;

The review of the literature revealed that there has been considerable debate associated with service quality due to the conflicting results reported in the literature with many adaptations to the gap based SERVQUAL (Parasuraman, Zeithaml & Berry 1988, 1985) model (Cui, Lewis & Park 2003; Aldlaigan & Buttle 2002; Newman 2001; Bahia & Nantel 2000; Harmen & Vriens 2000; Lee, Lee & Yoo 2000; Van Dyke, Prybutok & Kappelman 1997; Buttle 1996; Lam 1995; Gagliano & Hathcote 1994; Cronin & Taylor 1994; McAlexander, Kaldenberg, & Koenig 1994; Brown, Churchill, & Peter 1993; Cronin & Taylor 1992; Saleh & Ryan 1992; Bitner 1990; Carman 1990 and Babakus & Mangold 1989). The apparent result of the complexity surrounding service quality is that some researchers and academics appear compelled to develop alternative conceptualisations of the construct and to continue to study service quality (Al-Hawari & Ward 2006; Aldlaigan & Buttle 2002; Broderick & Vachirapornpuk 2002; Soteriou & Stavrinides 2000; Frost & Kumar 2000; Dabholkar, Shepherd & Thorpe 2000; Oh 1999; Sweeney, Soutar & Johnson 1997; Philip & Hazlett 1997; Spreng & Mackoy 1996; Dabholkar 1996; Dabholkar, Thorpe & Rentz 1996; Berkley & Gupta 1994; Bowers, Swan & Koehler 1994; Cronin & Taylor 1994; McAlexander, Kaldenberg & Koenig 1994; O'Connor, Shewchuk & Carney 1994; Headley & Miller 1993; Babakus & Mangold 1992; Lytle & Mokwa 1992; Mattsson 1992; Brogowicz, Delene & Lyth 1990; Carman 1990; and Haywood-Farmer 1988).

The purpose of this study was to develop and define such an alternative model. The proposed conceptualisation therefore draws on existing literature to develop a theory, which represents a fusion of the current literatures. One reoccurring theme that continued to emerge from the literature was the conceptualisation of service quality from a consumer's perception of product delivery and customer service outcome. This interaction is a critical part of the overall service product delivery and essential to customers' perception of service quality (Perrone & Ward 2006).

This study drew on a seminal and empirically tested model, the Grönroos (1984, 1982) Model of Perceived Service Quality that divided service quality into two dimensions, technical service quality and functional service quality. The combining of those two constructs and the addition of servicescape service quality provided an informed measure of service quality in developing a new proposed service quality model, PAWs Model of Future Customer Behaviour, to include the servicescape construct and customers post purchase perceptions and behaviours.

In one of the earlier research studies, the importance of managing the atmospherics of the retail environment was recommended to retailers as a means of targeting a customer's experience in this way (Kotler 1973). Further physical environmental research associated with retail providers established that a significant impact on the physical environment could be separated into specific categories; ambient factors, design factors and social factors (Wagner 2000; Bitner 1992 and Baker 1987). As a result of these servicescape models, perceived service quality encompassed all the physical elements influencing the service outcome, delivery and environment and the affects they have on the consumer.

Research has identified and supported numerous studies relating to the impact of consumer behavioural responses to environmental cues resulting in varying positions to marketing variables concerning the interior retail servicescape (Turley & Milliman 2000). Research further indicated that no previous empirical studies have examined the servicescape service quality aspect of the interior retail service setting using the constructs of the proposed theoretical framework with-in this study. The creation of a 'new model' therefore focuses on service based around customers' requirements of the internal retail environment thereby providing retailers with a clearer representation of consumer behaviour.

Based on this foundation, this study presents a framework beginning with the models of three independent constructs, product delivery, functional service quality and servicescape service quality. The two mediating constructs, customer satisfaction and relationship strength. These two dependent post purchase perception constructs indicated how customers reflect a service performance in terms of customer satisfaction and their perceived relationship with a retail service provider. Retention intentions and word-of-mouth communications made up the two dependent future customer behavioural constructs reviewed.

As is evident from the preceding literature review, there is considerable research examining the conceptualisation and operationalisation of perceived service quality. The following sub sections provide a review of the theoretical framework constructs identified.

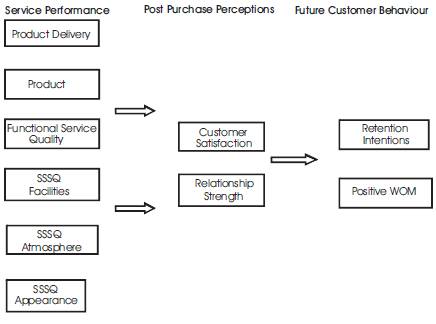

In developing the theoretical frameworks there were seven key constructs identified in the literature (product delivery, functional service quality, servicescape service quality, customer satisfaction, relationship strength, retention intentions and word-of-mouth). The theoretical framework distinguishes these constructs into three categories, Service Performance (product delivery, functional service quality, servicescape service quality), Post Purchase Perceptions (customer satisfaction, relationship strength), and Future Customer Behaviour (retention intentions and word-of-mouth). The aim of this study was to develop a new conceptual model, which empirically tested service quality relating to future customer behaviour.

The three service performance independent constructs measure consumer's expectations of service quality.

The two post purchase perception mediating variables measure consumer's perceptions of service quality as manifested in two perception variables:

Customer satisfaction relates to the overall satisfaction a consumer has with an organisation. The literature reviewed was analysed to provide an indicative representation of research studies resulting in customer satisfaction outcomes as they relate to retail industries because of its potential influence on consumer behavioural intentions and customer retention (Anderson & Fornell 1994; Bitner & Hubbert, 1994; Bolton & Drew 1994; Rust & Oliver 1994; Anderson & Sullivan 1993; Cronin & Taylor 1992; Fornell 1992; Oliver & Swan 1989; Oliver 1981, 1980, 1977, and Olson & Dover 1979). Customer satisfaction was perceived as being evaluative and an emotion based response to a retail encounter. Research then suggested customer satisfaction reflected the degree to which a consumer believes that the possession and/or use of a product evoked positive feelings (Jamal & Naser 2003). Some typical statements consumers may ask of an organisation would be, “has staff met my expectations, were services I received adequate, and did I enjoy the product(s)?”

Relationship strength the second post purchase perception construct measures the level of relationship between the consumer, an organisation and its staff (Bove & Johnson 2001; Naude & Buttle 2000; Ward & Smith 1998; Storbacka, Strandvik & Grönroos 1994; Crosby, Evans & Cowles 1990 and Gummesson 1987), by asking the questions as consumers, “Do I have a good rapport with staff? Do I trust the staff? Are staff approachable? Do they make me feel good about my purchases?”. In building relationships with customers, the literature reviewed suggested retail providers have focused on customer satisfaction as one measure in that process with other noteworthy predicting constructs of trust and commitment (Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner & Gremler 2002; Bove & Johnson 2001; Hennig-Thurau & Hansen 2000; Dorsch, Swanson & Kelly 1998; Ward & Smith 1998; Hennig-Thurau & Klee 1997; Hunt & Morgan 1994; Crosby, Evans & Cowles 1990 and Swan & Nolan 1985).

Researchers indicated that those retail service providers, through customer interactions, might be able to add value to their products by promoting a strengthening of those consumer relationships, which in turn may increase retention rates (Beerli, Martin & Quintana 2004). Relationship strength is believed to act as a mediating variable, as it is represented in this study, having an effect on behavioural intentions (Forrester & Maute 2001).

The two future customer behaviour dependent constructs of the theoretical framework measure subsequent consumer behaviour.

Retention intentions concerns a customers future purchase intention being a cognitive component of attitude. “Do I plan on returning to this retailer? When I purchase again will I make that purchase from the same organisation?”. Therefore, retention intentions is a behavioural intention with a subjective probability that consumers will perform some form of behaviour. Consequently, a customer's behavioural intention to continue to patronise an organisation may therefore be based upon their evaluation of the retail provider with a subjective probability the customer will repurchase the product in the future (Fishbein & Ajzen 1975).

Retention intentions may be influenced by a customer's intention to remain with a firm, knowing their product quality, which is based upon the customer's perceptions of the firm's technical (Grönroos 1990), functional (Grönroos 1990) and servicescape, (Bitner 1992) service quality as mediated by customer satisfaction and relationship strength.

Word-of-mouth, the second dependent construct measures a consumer's future referral intention. “Will I refer others? If asked to recommend an organisation would I tell them about the one I went to?” Word-of-mouth theory in the literature suggested that it is a result of consumer responses to the use of products or services associated with cognitive processes, such as perceptions of value and equity evaluations, which consumers experience and is shared as meaningful information with others (Westbrook 1987). Therefore, given this reasoning word-of-mouth is an activity that is likely to influence positive influences of a particular shopping experience (Babin, Darden & Griffin 1994). In this study, word-of-mouth communication is a future customer behavioural variable in the theoretical framework and may take into account the actual quality of the delivery of products provided by the retailer.

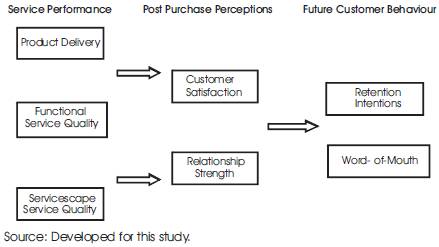

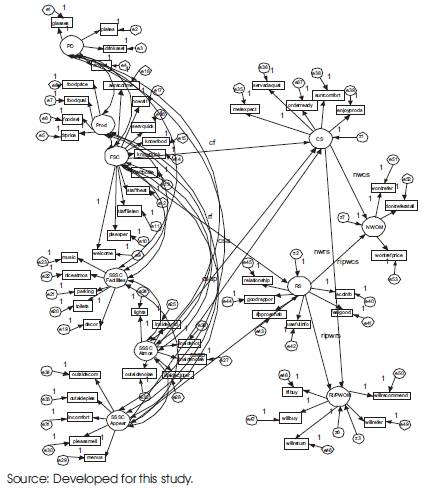

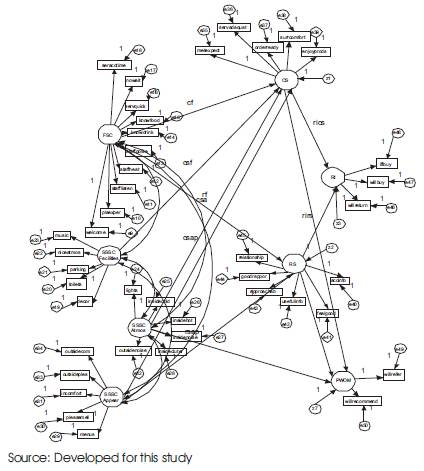

The proposed theoretical model contains seven constructs, three independent variables, two mediating variables and two dependent variables, as shown in Figure 1, illustrated model and Figure 2 structural model. The model postulates that the relationships between the constructs provides measures of service performance as evidenced through the service performance of the three independent constructs, Product Delivery, Functional Service Quality and Servicescape Service Quality. These three variables when combined with post purchase perceptions two mediating variables, Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Strength is proposed to predict customer post purchase behaviour.

Figure 1. Original theoretical illustrated model (Model 1)

Figure 2. Original theoretical structural model (Model 1)

Future customer behaviour is assessed, as noted, using two dependent constructs, Retention Intentions and Word-of-Mouth. In the coffee shop scenario used to test the model, the relationship between a customer and the retailer should be statistically related to: Service Performance as assessed by the three independent variables Product Delivery, Functional Service Quality and Servicescape Service Quality leading to Post Purchase Perceptions, as assessed by the two mediating variables Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Strength and then the outcome, Future Customer Behaviour as assessed by the two dependent variables Retention Intentions and Word–of- Mouth.

As there have been numerous research papers on servicescapes as well as the other service quality variables, this study provides for a wider understanding of consumers post purchase behaviour through the development of a new service quality model that combines servicescapes with those specific service quality variables. Therefore, this study addressed this gap to empirically support a service quality model on future customer behaviour and by testing a new theoretical framework.

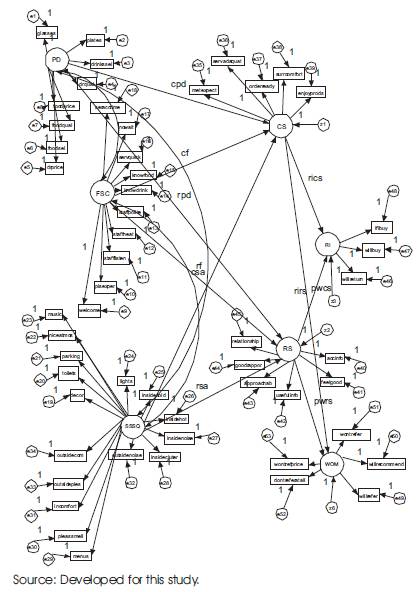

This section provides a brief description to the method used in the collection and analysis of the data for this study. This study employed exploratory and descriptive research design methods in a two stage process with Stage 1 (exploratory), utilising focus groups and personal interviews, and Stage 2 (descriptive), using quantitative methods for the main data gathering by administering a structured self administered survey. The purpose of Stage 1 was to inform the construction of the test instrument for Stage 2 (Kvale, 1996; Thompson, Locander & Pollio 1989 and Hudson & Ozanne, 1988).

In Stage 1 qualitative methods were used to initially explore consumer's behavioural responses to coffee shop patronage. During the process of conducting interviews and focus groups, insights and perspectives were obtained to provide initial contextual information that enhanced the researcher's knowledge about the research being conducted. The Stage 1 process also assisted the researcher in clarifying the phenomenon being investigated and to identify with the research issues (Hair, Bush & Ortinau 2003; Zikmund 2003; Churchill & Iacobucci 2002 and Cooper & Emory 1995). For this exploratory phase there were a total of 43 participants representing service providers and customers. Two traditional focus group formats were conducted with 17 participants.

During the Stage 1 process an initial survey was constructed arising from a progression of interview and focus group data, consultation with other academics, researchers, consumers, retailers and colleagues thereby developing an understanding of customer attitudes and behaviours when using a product and their criteria in selecting a retail service provider (Edvardsson 1998 and Hayes 1997). The interview process had five primary goals:

The expression of free flowing discussion of the focus groups, coupled with the flexible format, allowed the participants to discuss the research topic with conviction, limited anxiety and inner personal beliefs and feelings as a spontaneous and mutual expression (Sarantakos 2005; Zikmund 2003; Greenbaum 2000 and Blankenship, Breen & Dutka 1998). The focus group format was also advantageous to the pilot study as it provided critical comments and perspectives required in the development and administration of the data to be captured by the test instrument (Aaker, Kumar & Day 2001; Kinnear & Taylor 1996 and Churchill 1995).

In Stage 2, the quantitative data gathering phase, the test instrument was developed to measure the seven main variables of the study with the information obtained from the findings of Stage 1 and the literature reviewed for the study. The data gathering process entailed surveying members of the public who were a random sample from patrons of coffee shops in the greater Melbourne, Victoria Australia area. The data sample consisted of 500 usable test instruments that were stratified by obtaining 50 responses from participants in each of ten different coffee shop locations.

During data analysis descriptive statistics, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), were conducted, which was a first step prior to analysing the research data using structural equation modelling. Descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS 15.0, which prepared the data providing details describing a set of factors for this study (Sekaran 2003). This process was followed by EFA and then assessment of the measurement model using CFA. Finally, hypotheses testing of the relationships using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) were conducted with AMOS 7.0 software. As noted Structural Equation Modelling was used to analyse the data and as this research was grounded in a positivism theoretical design, SEM was considered appropriate as the relevance of positivism is complementary to SEM analysis (Guba & Lincoln 1994 and Hunt 1991).

The data gathered during Stage 2 was used to test the competing models developed for this study with the data analysis process described in the next section. During the analysis four models were evaluated to determine best fit indices and by testing the various models to see which set of variables were most significant. This included eliminating all non significant variables and pathways resulting in the most parsimonious model for this study. The process of testing the different models included assessing the original theoretical model with subsequent assessing of the structured models to find the most parsimonious fit model (Kline 1998 and Hulland, Chow & Lam 1996). Figure 3 provides a summary of the design process undertaken in Stage 2 to develop optimum measurement of the variables.

Figure 3. The overall method

The pre-analytical process of the data preparation process ensured that the data were complete and accurate by coding, transcribing or the entering of the data into a computer database and accounting for missing responses to further ensure the results could be meaningfully interpreted from the data (Trochim 2003 and Malhotra 1999). This process included conducting tests for outliners, descriptive statistics of demographic variables, undertaking data transformation and ensuring scale validity and reliability were additionally explored to ascertain a better representation of the data (Sekaran 2003).

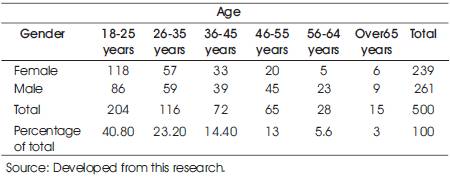

The demographic profile of the respondents from the coffee shop samples are shown in Table 1. The table provides the age/gender breakdown for all 500 surveys that were administered. Of the 700 consumers asked to participate in answering the survey, 500 usable test instruments were completed resulting in a response rate of 71.4 percent, which was quite high for business research (Neuman 2003 and Malhotra 1999).

Table 1. Age /Gender Crosstabulation

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was utilised to examine the factor structure and its fit with the data thus ensuring the items of the survey actually measured the variables they were designed to measure. EFA measured the factorisability of each group of items providing an overview of the factor structure. To control for possible confounding of the data sample, the initial sample of 500 participants was divided into 200 (EFA) and 300 (CFA) data sets respectively. This process controlled the effect of the confounding of participant data in relating the findings of the EFA to the CFA.

Components analysis was then utilised for initial extraction of factors followed by an oblique rotation. The EFA test was conducted to identify items that did not significantly load on factors (Keen 2007; De Vaus 2002; Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum & Strahan 1999 and Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black 1995).

EFA was conducted to verify that the indicator variables of this study aligned with the constructs, which were theoretically proposed including the scale reliability of each of those factors, EFA confirmed that most of the indicator variables did align with the theoretically proposed constructs. Of the seven main constructs, Product Delivery split into two factors, Products Delivery and factors, SSS Facilities, SSS Appearance and SSS Atmosphere. For the variable Word-of-Mouth two positive indicator items aligned with the construct, Retention intentions forming a re-labelled construct Positive Word-of-Mouth (PWOM), while the three negative indicator items remained together thereby being labelled Negative Word-of-Mouth (NWOM).

As the three negative indicator items resulted in a lack of negative correlation with PWOM factor, it was determined that they would be subsequently removed from the study. As theoretically proposed the dependent constructs of Retention Intentions and Word-of-Mouth, through the literature reviewed, are two distinct behaviours therefore in keeping with the theory, the constructs were subsequently split into two distinct variables thereby creating a ten factor model with two dependent constructs, RI and PWOM, as was theoretically proposed. Those items that did not load on a factor were subsequently deleted thereby producing a more than adequate pool of items for each of the factors for further analysis to be performed through CFA.

Following EFA analysis the original theoretical model was developed into four models for comparison using confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modelling. Following is a brief description of each model:

Figure 4. Revised theoretical illustrated model (Model 2)

Figure 5. Revised theoretical structural model with RI/PWOM & NWOM

Figure 6. PAWs illustrated model of Future Customer Behaviour (Model 3)

Figure 7. PAWs structural model of Future Customer Behaviour (Model 3)

Figure 8. Illustrated model without the servicescape variable (Model 4)

Figure 9. Structural model minus SSSQ with RI and PWOM split (Model 4)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to demonstrate empirically that the hypothesised model fits the data and CFA confirmed the factor structure and the identification of the underlying factors as produced by the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) (Bollen 1989 and Anderson & Gerbing 1988). The distinction between EFA and CFA is not always clear cut therefore CFA results were used to incrementally re-define the measurement models (Gerbing & Hamilton 1996; Bollen 1989 and Anderson & Gerbing 1988). To confirm that the measurement items were adequate using CFA, the proposed model for this research was estimated by conducting evaluations of its overall statistical fit, goodness-of-fit criteria and the subsequent assessment of fit of the model.

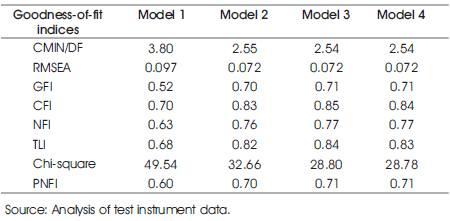

The conceptual model developed puts forward service quality as comprising seven primary constructs, product delivery, functional service quality, servicescape service quality, customer satisfaction, relationship strength, retention intentions and word–of-mouth. A CFA test was then conducted on the four models with the results tabulated at Table 2 for comparison.

Table 2. CFA summary of model fit statistics for the four proposed models

In summary, during the CFA process all factor loadings were estimated (freed), so that items were allowed to load only on one construct with no cross loadings. The research also met some basic criteria for CFA testing; 1) sample size, 300 test instruments, sixty percent, of the original sample of 500 surveys were used, which was more than adequate (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black 1995 and Anderson & Gerbing 1988), and, 2) as there was normal distribution of the variables, the maximum likelihood discrepancy function was appropriate for the complexion of the data collection process (Bentler & Dudgeon 1996).

Other assessment factors evaluated were Cronbach alpha, the significance of Barlett's Test of Spherity and the KMO, variance extracted and goodness of fit indices for the models satisfying the acceptable requirements based on these tests for good model fit. The fit indices (Table 2) for the four models all fitted well with the survey data with Model 3, PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour, proving to fit the data best.

The next step in the evaluation process involved comparing models (Kline 2005and Anderson & Gerbing 1988) using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) as an analytical tool, which has been a successful approach for marketing research (Baumgartner & Homburg 1996). In order to decide which SEM model was the most parsimonious, the process of eliminating non-significant pathways and subsequently variables did yield the most significant and parsimonious model as presented in Figures 10 & 11. Those variables and items that were removed were in relation to Product and Product Delivery as the data indicated those two constructs and relating items had little effect on the overall outcome.

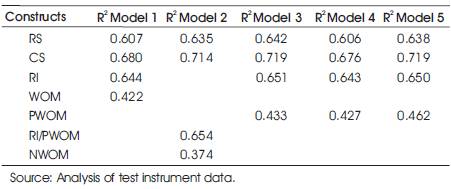

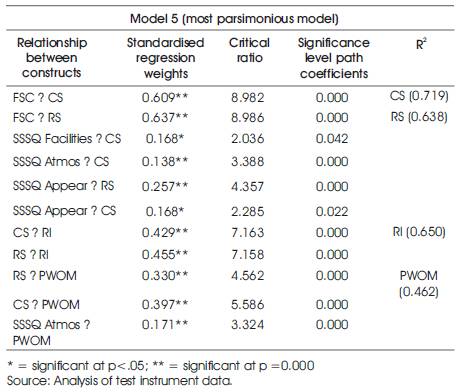

The most parsimonious model is the simplest that gives a high R2 but not necessarily the highest R2 thereby providing a trade off between complexity and power as the R2 shows the best predictor model. Table 3 presents and compares the five models R2 with all five indicating they had significant results. Model 5, the most parsimonious model, is highlighted.

Table 3. Summary of R2 for the five proposed models presented

Figure 10. Most Parsimonious illustrated model (Model 5)

Figure 11. Most Parsimonious structural model (Model 5)

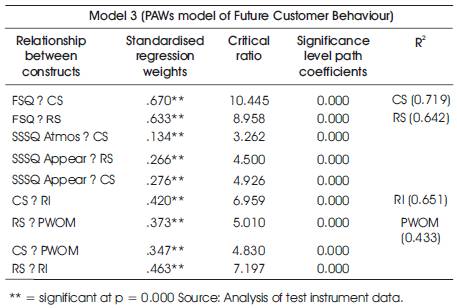

The testing indicated that Model 3, the PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour, presented fundamentally sound with the theoretical framework including having acceptable fit indices. The results indicated that the PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour was an acceptable model and would therefore be a reliable model to use in the testing of other service settings. The PAWs model also revealed that the servicescape construct did have a marginally better result than Model 4, which was tested without the servicescape construct for this particular study.

Having determined and established the final structural equation model, Model 3, examination of the path coefficients and the significance levels between the constructs of the model was conducted. A critical ratio, an index used to determine the significance or non-significance of a structured path, were deemed significant if they were greater than a conventional threshold of ±1.96 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black 1995). The critical ratios of all paths were significant. The standard regression weights and path significance for Model 3 PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour and Model 5, most parsimonious model are presented in Tables 4 & 5.

Table 4. Standardised regression weights and path significance levels

Table 5. Standardised regression weights and path significance levels

Finding 1 - As a first step approach in the evaluation process, the theoretical model was analysed to establish data fit with relative changes taking place in factor loadings of the theoretical model. A revised theoretical model presented a modification to the original theoretical framework with a resulting ten factor model, Model 3, with the construct product delivery splitting into two distinct factors as per the factor analysis and with the servicescape construct splitting into three factors. The analysis showed an increase in the number, from three to six, of service performance variables as a result of the splitting of product delivery into product and product delivery and servicescape service quality into servicescape service quality facilities, atmosphere and appearance.

The analysis also showed that the future customer behaviour constructs, word-of-mouth partially combined with retention intentions with two positive indicator items moving to the retention intention construct while the three negative word-of-mouth items remained as a separate construct. However, retention intentions and word-of-mouth are two distinct behaviours and therefore were subsequently split into their respective constructs. The three negative word-of-mouth items represented negative response factors, which were contrary to the construct they were conceived therefore they were subsequently removed from the scale and from further analysis.

Most importantly the complete theoretical model, the PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour (Model 3) resulted in significant R2 for the constructs, RS (R2 =0.642), CS (R2 =0.719), RI (R2 =0.651) and PWOM (R2 =0.433) indicating empirical support, including having acceptable fit indices thereby being an appropriate model to use in the testing of other service settings.

Finding 2- Having arrived at the complete theoretical model through EFA and CFA, in order to decide which SEM model was going to be the most parsimonious, the process of eliminating those non significant paths and subsequently constructs delivered producing the most parsimonious model. Through the removal of all non significant elements of the SEM model, one of the original conceptual constructs, product delivery, which had been split into two distinct constructs through factor analysis, was removed from the model.

Finding 3- The initial theoretical framework outlined that the services cape service quality construct was represented as a single variable. However, as indicated by the literature reviewed, some researchers (Wagner 2000; Bitner 1992 and Baker 1987) made reference that the services cape environment was comprised of more than one element in its configuration. The factor tests conducted revealed that the services cape construct did split into three distinct components, appearance, atmosphere and facilities, and are presented as such in the model. Therefore, in order to test if the services cape did in fact play a significant role in the predictive powers of the model a comparison test took place. The test conducted was on the model without the services cape construct to determine if the exclusion of the services cape construct significantly affects the relationship between service quality as measured by the other constructs of the model and the impact on customer perceptions and future behaviours.

The results of the revised model without the services cape construct indicated that the model was significant with high R2 and acceptable model (Model 4) fit statistics for the χ2 value, level of significance of χ2/df and relative goodness of fit indices statistics. The results of the data obtained for this study, from a coffee shop setting, also revealed that the exclusion of the servicescape service quality construct had similar fit indices outcomes, as the complete ten factor model (PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour Model 3) did with the servicescape inclusion. However, PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour Model 3 with the servicescape produced a higher yielding R2 , RS (0.638), CS (0.719), RI (0.650) and PWOM (0.462),than the Model 4 tested without the servicescape construct, RS (0.606), CS (0.676), RI (0.643), PWOM (0.427), concluding that the model with the inclusion of the servicescape was more parsimonious than the model tested without the servicescape construct thereby providing a predictive model with high predictive powers.

The research contributes to marketing theory in several ways with a major contribution being that the conceptual and subsequent accepted model, PAWs model of Future Customer Behaviour (Model 3) being the first known research concerning the interaction and grouping of the service quality various constructs presented in this fashion.

These additions provided for, 1) a better understanding of how services are evaluated by users, which indicated greater understanding of how to influence and manage these customers' evaluations; and, 2) stronger relationships between customer service quality and future customer perceptions and behaviours. Therefore, the research makes four contributions to the literature by:

Competing models were tested by goodness of fit indices tests and the strength of the models R2 values. Through this process a modified model, of the generalised theoretical model resulted, which produced acceptable fit and strong R2 values for the mediating and dependent variables. The model testing resulted in a more parsimonious model being produced relative to this research on coffee shops. This parsimonious model resulted in eight constructs, with the original product delivery construct having been split into two distinct construct, being removed as not being a significant factor through analysis. These results indicated that through the data collected customer service quality was indeed affected by the retail services cape.

The combination of the original seven constructs indicated that when they are combined and tested in a retail environment it can be concluded, relative to the theory provided in the literature reviewed and confirmed through data analysis, they are affective tools in measuring the contribution that the retail services cape makes to customer service quality. The complete theoretical model also splits the servicescape construct into three components, appearance, atmosphere and facilities thereby strengthening the models testing ability of customer service quality in a service setting.

Although the tests indicated strong results the impact of the servicescape construct overall was small thereby opening up the possibility that the servicescape construct could produce much stronger results in other service setting situations. The literature also revealed service quality played an important role in a service provider's success or failure by acknowledging the behavioural relevance the retail servicescape has on customer service quality in one retail setting, coffee shops.

This research is of much importance for the service industry as the significance on customer perceptions of the servicescape on customer satisfaction has had little empirical testing and from this study clearly has a significant affect on a consumers overall perception of satisfaction. As indicated the predicative powers of the model with the inclusion of the servicescape construct produced stronger R2 values than the model without the servicescape construct. The result gives a strong indication that the addition of the servicescape in the retail setting of a coffee shop provides a better result than without the servicescape, therefore demonstrating the servicescape is necessary due to its influence on consumer perceptions of satisfaction.

This research empirically identified and measured the relationship between servicescape and the two future customer behaviour dependent variables, retention intentions and positive word-of-mouth. The predictive powers of the model identified the interrelationships between the constructs as indicated, with the inclusion of the servicescape construct, by producing a stronger R2 value than the model without the servicescape. It was also found that there was a significant positive correlation to those two customer post purchase behavioural variables and those consumers are impacted by service performance as mediated by post purchase perceptions.

Through the literature reviewed, there were several service quality models presented that used a combination of constructs to measure customer's perceptions, relationships, satisfaction and behaviours. However, no models were identified that used the service performance independent variables of this study to measure service quality as they are presented in this research. As a result, these generalised variables were grouped into a theoretical framework, to be tested. Construct inclusion in the conceptual model was based on other researchers studies such as seminal research conducted by Grönroos (1990, 1982). The Grönroos Model of Perceived Service Quality included in its model the technical (product delivery) and functional service quality variables. The combination of those two constructs and the addition of the other service quality constructs formed part of the model with the most significant addition being the servicescape construct. It was the inclusion of the servicescape and the particular grouping of the other service quality variables that has distinguished this researches model from those presented in studies previously thereby ultimately playing, as a collective, a significant role in the development of service quality perceptions. This research also provides future researchers with an empirically tested generalised proposed model to be used for other research in various service settings.

In summary, the major contributions to theory are:

Owners and marketing professionals in the service industry should fully understand that the delivery of high quality service, an accommodating environment, instilling feelings of trust and satisfaction with their customers will more likely lead to the long term relationship commitments, of customer retention and positive referrals. This research has identified customer retention as a significant element of the customers post purchase behaviour and as mediated by relationship strength and customer satisfaction. Positive referrals have also been identified as having an affect on that commitment due to its importance on customer's perceptions of the servicescape and its significant impact on consumer satisfaction and relationship strength.

Relationship strength was positively related to the customer service provided and the overall appearance of the services outlet. Satisfaction was positively related to the customer service provided, the facilities, atmosphere and appearance of the environment. Positive referrals of customers perceptions of the servicescape were positively related to the atmosphere provided. Therefore service provider's and marketing professionals need to ensure that service quality is provided to their patrons in such a way as to distinguish and instil a level of confidence in the set of competencies that are valued by their clients as meeting their required level of needs.

This subject would imply that the service provider would fully understand what those consumer needs are in the first instance, which would be consistent with the underlying transactional marketing relationship between a customers post purchase behaviour and the retail servicescape.

Service providers and marketing professionals therefore need to fully understand the requirements relating to relationship strength and the affective recruitment of staff are aligned to the important outcome in its relationship building with their patrons. Staffs need to be able to instil not only trust but satisfaction as well and to demonstrate an understanding of their customers needs. Consequently, as a result internal training programs should reflect the requirements for optimum development of customer relationships, which will garner retention and in turn generate positive referrals.

Specifically, coffee shops could link Key Performance Indicators (KPI) to training programs to these requirements'. Those KPI's would measure the customers post purchase behavioural patterns and the inputs that affect that behaviour such as those identified in this study. For example, KPI's could be established to measure inputs such as retention rates, satisfaction, relationship strength, referrals, customer service and the overall servicescape, facilities, appearance and atmosphere, together with an overall measure of post purchase behaviour. This approach would answer the question as to whether the retail coffee shop, for this studies purposes, was truly committed to sustaining and building a relationship with their customers, or why they were not. The onus and emphasis would be on those coffee shops in ensuring that the correct operationalisations of measures are established to obtain the correct results.

Coffee shops would also need a monitoring system capable of measuring their clients repeat business. This is a logical path as retention was identified in this study as being highly significant in its relationships with other antecedents. Repeat customers are an important financial benefit for coffee shops, as most are relatively small retail establishments, revenues and profits would therefore be instrumental to the coffee shops success and in turn potential market share growth. It would also allow the coffee shops to monitor repeat business intentions and identify and take the necessary steps for those customers who may be at risk of not returning and going to a competitor. Having this knowledge and the factors that would lead up to repeat business, coffee shops could use these insights to implement strategies that would encourage customer continuity and build stronger relationships.

Coffee shops could also seek to instil customer advocacy, positive referrals, from loyal patrons especially if those customers are of an influential nature with friends, family and acquaintances in the wider community. By doing so retail coffee shops are more than likely to benefit from repeat and referral business, both constructs that yielded high significance in this study. Referrals are normally associated with share market growth thereby reducing the capacity for competitors to benefit from shared relationships with same customers. Although repurchase intentions and word-of-mouth were identified as being highly significant factors leading to customer post purchase behaviour, other factors such as customer satisfaction and relationship strength also contribute, albeit indirectly.

Although two of the six independent constructs were not significant predictors of retention intentions and positive word-of-mouth in this study (product and product delivery), they should be included in future research. Individual studies will then either empirically support or reject their inclusion.

Although this study provides significant insights into customers post purchase behaviours, there were five limitations identified.

This study has provided some recommendations for future research. Research is needed to validate and generalise the findings to broader settings examining similar study objectives in various service sectors such as; hospitality, banking, and apparel retailers. Each sector should have large samples representing consumers from a variety of service organisations paying close attention to the research design.

This research is of much importance for the service industry as the significance and size of effect on customer perceptions of customer satisfaction of the servicescape has had little empirical testing and from this study clearly has a significant effect on the customers overall perception of satisfaction. As this study explored relationships between customer perceptions of the servicescape in a coffee shop setting, further research may explore those relationships from the perspective of management or staff. This would certainly advance understandings of the topic.

When testing the theoretical framework in other service settings future research could examine whether consumers are influenced by varying concepts such as brand imaging and its applicability in various service settings like retail environments. Further research could integrate a third mediating variable 'brand image' in the theoretical framework providing additional insights into the relationship between customers brand imaging awareness levels and their subsequent behavioural response to the surrounding servicescape.