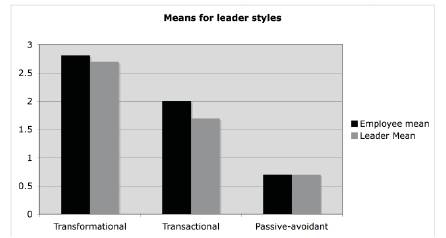

Figure 1. Histogram of Means of Styles As Reported by Leaders and Employees

Leaders may lack an understanding of what leader behaviors enhance job satisfaction and organizational culture. The purpose of the quantitative correlational survey study examined the relationships between leadership styles, job satisfaction, and organizational culture in small animal veterinary hospitals. Data from The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, the Organizational Description Questionnaire, the Job in General and Job Descriptive Index, revealed that leader transformational behaviors are positively correlated with the work, promotion, and supervisor facets of job satisfaction. Transactional culture is positively correlated with all facets. Training leaders to improve aspects of transactional culture and to enhance transformational behaviors may improve overall job satisfaction, satisfaction with pay, and satisfaction with opportunities for promotion.

Current research has suggested that employee development practices are the most important business practice that leads to high incomes for veterinarians (Volk, et al., 2005). The focus of this research was to examine leadership styles that affect job satisfaction and organizational culture, thus leading to better employee development practices in small service businesses, specifically veterinary hospitals.

An indication of job satisfaction is employee turnover (Harris & Brannick, 1999). Approximately 36% of employees are actively seeking another job, with slightly fewer not satisfied with their current positions but not actively seeking reemployment (Hilpen, 2006) . High employee turnover increases a business' expenses (Amburgy, 2005) , and when expenses are increased, less money is available to increase the pay of the remaining employees. Pay rates, a good employer, and recognition are all factors that encourage employees to remain (Hilpen). These factors may correlate with the employee development practices mentioned as one of the important business skills identified by an American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) study (Brakke Consulting, 2005) . Understanding the relationship between leadership and employee development practices, as related to job satisfaction and culture , may be a critical element in maintaining a healthy veterinary practice.

The economic health of veterinary practices is important for viability of the business, but is also critical for the staff members. In May of 2004, veterinary technologists and technicians earned a median income of $11.90 an hour (U.S. Department of Labor, 2006) . Other animal-care service workers earned a median income of $8.39 an hour. The average salary for lay and paraprofessional workers in veterinary hospitals is $20,290, which was $1440 over poverty level in 2004. If the owners of the hospitals are not able to increase the efficiency of their hospitals through increased business acumen or improved behavior, hospital staff will continue to experience a high rate of turnover as employees seek better wages elsewhere.

The AVMA-Pfizer study (Brakke Consulting, 2005) indicated that the personal income of veterinarians was $34,470 higher for veterinarians who employed practices to promote their employees' longevity. Given that veterinarians rank among the lowest paid of nine measured professionals (Brown & Silverman, 1999) , the added income from promoting longevity may improve the economics of veterinary practice. Nonveterinary staff-member compensation typically accounts for 23% of the total revenues of a veterinary hospital (Wutchiett, Tumblin, Flemming, & Lawson, 2005) . Because such a large portion of the hospital's revenues are spent on lay and paraprofessional salaries, the staff's general satisfaction and intention to remain in the practice can have a significant financial and cultural impact on the practice.

The purpose of this quantitative survey study was to determine if there is a relationship between transformational, transactional, and passive avoidant leadership styles and job satisfaction and organizational culture for leaders and employees. Veterinary hospital leaders and other small service businesses would benefit from knowing what styles could be associated with high levels of job satisfaction and optimal organizational culture within their organizations.

Intention to leave a job, turnover, absenteeism, withdrawal, and reduced commitment are all signs of employee burnout and have a significant negative effect on the overall morale of a company as well as on productivity (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001) . Maslach et al. further noted that a number of job characteristics contribute to burnout, among which are lack of social support from supervisors and coworkers, lack of ability to participate in decision making, and lack of feedback. The responsibility of the leaders in organizations is to assure the culture is conducive to employee satisfaction and to modify the culture if necessary (Schein, 2004) . Linking specific leadership styles to cultural issues and to job satisfaction may help veterinary practices reduce turnover and increase productivity and morale.

Specifically, the data resulting from this research helped to answer two questions. Research Question 1 was, what is the relationship between transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership styles, as defined in the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), and employee satisfaction, as defined in the Job in General (JIG) and the Job Description Index (JDI)? Research question two was, what is the relationship between transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership styles, as defined in the MLQ, and organizational culture, as defined in the Organization Description Questionnaire (ODQ)? For a definition of leadership and organizational terms, please refer to Appendix A.

The MLQ survey instrument was used to determine transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant styles of the leader as measured by his or her followers and by self-assessment. Job satisfaction of followers was measured using the JDI and JIG, and organizational culture was measured using the ODQ survey instrument.

H01: No relationship exists between transformational, transactional, or passive-avoidant leadership styles, as measured by the MLQ, and employee satisfaction, as measured by the JIG and JDI in small animal veterinary hospitals.

H02: No relationship exists between transformational, transactional, or passive-avoidant leadership styles, as measured by the MLQ, and organizational culture, as measured by the ODQ in small animal veterinary hospitals.

The (MLQ) was completed by the owners or administrators of participating veterinary practices who were actively involved in the daily functions of the hospital. The MLQ was completed by all the participating employees of participating hospitals.

The owners and/or administrators also completed the Organizational Description Questionnaire (ODQ). The employees completed the job satisfaction instruments (JIG and JDI) as well as the ODQ.

The (JDI) measured work on present job, present pay, opportunities for promotion, supervision, and attitude towards coworkers. Each of these facets uses nine to eighteen questions in a yes/no/? format to determine workers' satisfaction in each of these areas.

The Job in General (JIG) scale measured global job satisfaction in a yes/no/? format. Together with the JDI, the tests gave an excellent overview of an employee's job satisfaction, performance outcomes, and intentions about staying or leaving (Bowling Green State University, 2006).

The population for this quantitative, correlational analysis included 340 veterinarians representing approximately 84 hospitals in the four-county region of Florida consisting of Pinellas, Manatee, Sarasota, and Hillsborough counties. Approximately 221 of the 350 veterinarians who were mailed requests were qualified to participate. Because there is only one leader per hospital, the 30 responding leaders represented 36% of qualified leaders. There were approximately 254 qualified employees of which 137 participated for response rate of 54%.

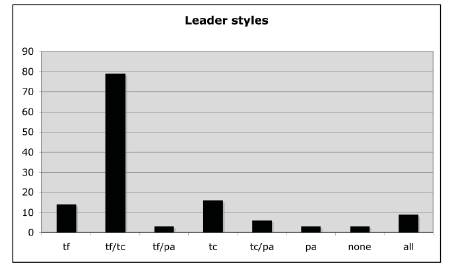

The 136 employees and the 30 leaders who responded to the leader rater survey that is part of the MLQ reported mean values for transformational leadership at 2.8 and 2.7 respectively. The mean values for transactional leadership were 2.0 and 1.7 respectively. The mean values for passive-avoidant leadership were 0.7 and 0.7 respectively (Figure 1). The means, standard deviations, and skewness of each leader style as reported by leaders and employees are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1. Histogram of Means of Styles As Reported by Leaders and Employees

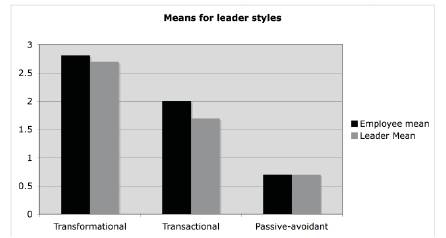

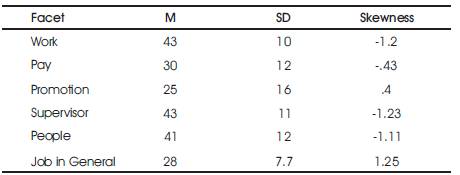

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Leadership Styles

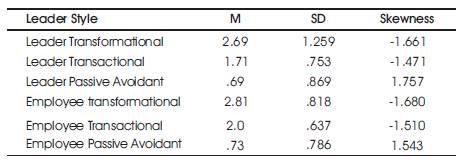

Avolio and Bass (2004) report that population means for the transformational style at 2.85, the transactional style at 2.27, and the passive avoidant style at 0.84. Typically, the leaders' ratings of themselves are lower than the raters' (Avolio & Bass) . Values of over three constitute transformational behavior, over two indicate transactional behavior, and over one indicates passive avoidant (http://www.mindgarden.com/products/ mlqr.htm). Using these standards, leaders often fell into one or more behavior categories, and they are labeled here as transformational (TF), transformational/ transactional (TF/TC), transformational / passive-avoidant (TF/PA), transactional (TC), transactional/passive-avoidant (TC/PA), passive-avoidant (PA), leaders who display no solid leadership behavior (NONE), and those who display all of them (ALL). Based on this identification scheme, the most common style was transformational / transactional Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pareto Chart Representing Reported Leader Styles by Employees n=133

As detailed in the instrument section outlining the JDI and JIG scales, 18 questions, which are posed using adjectives, are asked that help the respondent to evaluate his or her feelings regarding the job. For each scale, the maximum score is 54, so the neutral point is 27, which is exactly in the middle. Scores well above 27 indicate high satisfaction, and those under 27 indicate high dissatisfaction (Balzer et al. 1997) .

One hundred thirty four employees responded to the JDI and JIG instruments. Employees rated above neutral their satisfaction with their work, supervisors, and co-workers (Table 2).

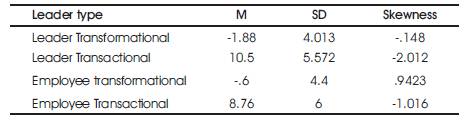

Table 2. JDI and JIG descriptive statistics

While not related to the research questions or hypotheses, several outcomes arising from the analysis of the data can be noted. First is the relative satisfaction employees reported, keeping in mind that a score of 27 represents neutral, 54 perfectly satisfied, and 0 as not at all satisfied. The facets with which employees appeared most satisfied were supervisors with a mean of 43, the work they do at 43, and their co-workers at 41. The mean scores for employees' satisfaction with their pay were 30, with their opportunities for promotion at 25, and their jobs in general at 28 (Table 2). Low pay and a job with no upward mobility appear to decrease employees' abilities to be completely satisfied with their work. Tumblin (2006) and Veterinary Economics (2006) supported the findings that employees' pay, opportunities for promotion, job satisfaction, and intention to leave were related.

Thirty leaders and 136 employees answered the questions on the Organizational Description Questionnaire. All were asked to complete the ODQ. Please see table below for the results. (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for Organizational Culture Scores

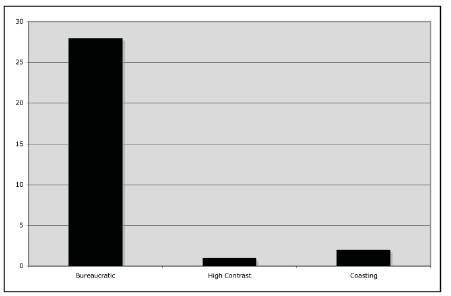

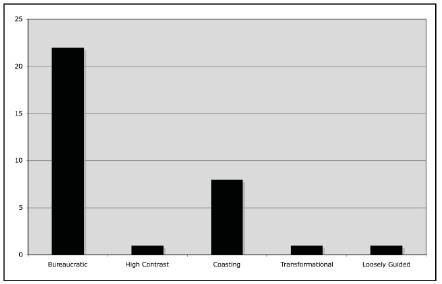

Employees identified five organizational culture types and the leaders reported three. Employees identified transformational, high contrast, bureaucratic, coasting, and loosely guided while leaders reported bureaucratic, high contrast, and coasting (Figures 3 and 4). Both groups reported bureaucratic organizations more often than any other.

Figure 3. Histogram Of Leader Reported Culture Types

Figure 4. Histogram of Employee Reported Culture Types

Correlations Between Leadership Styles and Job Satisfaction

What is the relationship between transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership styles, as defined in the MLQ, and employee satisfaction, as defined in the JIG and JDI?

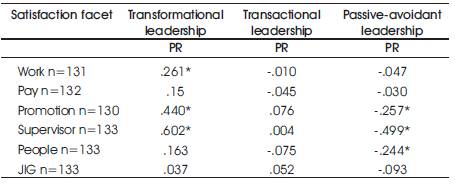

Transformational leadership as reported by the employees positively correlated with three of the six facets of job satisfaction, which included their work, opportunities for promotion, and their supervisors.

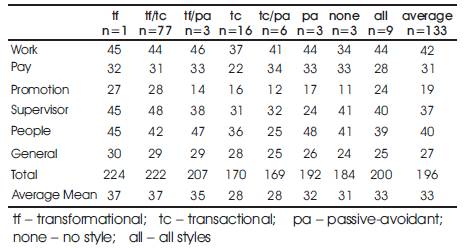

Transactional leadership did not correlate with any of the facets of job satisfaction. Passive avoidant leadership negatively correlated with three facets, employees' opportunities for promotion, satisfaction with their supervisor, and satisfaction with their co-workers (Table 4). Scores for transformational, transactional, and passive avoidant leadership are considered together to determine the overall leadership style. If the transformational score was over 3, the leader was labeled transformational. If the transactional score was over 2, the leader was labeled transactional. If the passive-avoidant score exceeded 1, the leader was labeled passive avoidant. Many leaders fell into more than one category, and some did not fall into any. Each leadership style is compared to the means for each facet of job satisfaction in Table 5.

Table 4. Correlations between Leadership Styles and Satisfaction Facets According to Leaders

Table 5. Leader Styles And Job Satisfaction Means

Any leadership style that included transformational behaviors rated highest. The highest average means were associated with the transformational style, and transformational / transactional style. These means were followed closely by the transformational / passive avoidant style and when all leadership styles were used. The only two types of leader styles that exceeded the average mean in all job satisfaction categories were transformational, and transformational/transactional.

The correlations between leadership styles and job satisfaction resulted in supporting the directional hypothesis, H11: A relationship exists between transformational, transactional, or passive-avoidant leadership styles, as measured by the MLQ, and employee satisfaction, as measured by the JIG and JDI in small animal veterinary hospitals . Specifically, there is moderate support for H11 where satisfaction with supervisor and opportunities for promotion are correlated with transformational leadership. Using Creswell's (2002) definitions of strength of correlations, there is slight support for the positive correlation between satisfaction with the work and transformational leadership, and a slight negative correlation between satisfaction with co-workers and passive avoidant leadership (Table 4).

While employees reported being generally satisfied with their work, it appears that they are happier when a leader exhibits a transformational style (Table 4). If leaders attempt to be more transformational in their behaviors, satisfaction may increase in veterinary hospitals. Because more satisfied employees will generally result in lower turnover (Gallup, 2006; Tumblin, 2006) , there may be financial and stability benefits to veterinary hospitals if a leader can train to become more transformational in his or her behavior. Bass (1999) stated that when leaders have made the effort and have received training regarding how to improve transformational leadership abilities, the leaders have experienced generally positive results.

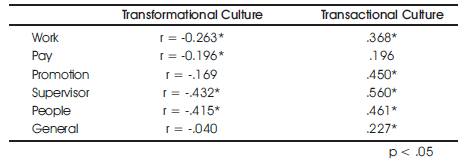

While not associated with the research questions or hypotheses, correlations were found between job satisfaction scores as reported by employees and organizational culture scores. Using Creswell's (2002) and Leedy and Ormrod's (2005) definitions of strength of correlations, there was a negative correlation between transformational culture scores and all six facets of job satisfaction, and two of those correlations were moderate; satisfaction with employees' supervisors and co-workers. A slight negative correlation existed between transformational culture and satisfaction with pay. Positive correlations were shown between transactional culture scores and all job satisfaction scores, and the correlation was moderate with the employees' work at present job, employee's opportunities for promotion, satisfaction with employees' supervisors and co-workers. The correlation between transactional culture was slight positive when compared to the employees' work on the present job and their jobs in general (Table 6).

Table 6. Correlations Between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Culture Scores

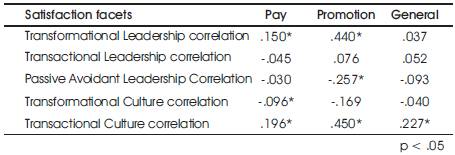

Upon comparison, it appears that leadership styles that result in transformational leadership behaviors net the highest overall job satisfaction (Table 4) Likewise, organizational cultures that are more transactional net higher job satisfaction (Table 6). Because job satisfaction facets for supervisor, work on present job, and co-workers are already high in veterinary hospitals, a focus on behaviors and cultures that cause an increase in satisfaction in pay, opportunities for promotion, and job in general might be beneficial. An analysis of the data suggests that a transactional culture is correlated with slightly higher satisfaction with pay, and opportunities for promotion than is transformational leadership (Table 7). Transactional culture is more highly correlated with the job in general than transformational behaviors.

Table 7. Correlations Between Certain Job Satisfaction Facets and Leader Styles and Organizational Culture

The Organizational Description Questionnaire (ODQ) nets several outcomes. There is an overall transformational score and an overall transactional one. These scores indicate the general nature of the culture and can vary from -14, which represents that the culture being tested is not at all present, to 14, which represents that the culture being tested is pervasive. Bass and Avolio (1992) combine the scores for nine organizational types (Appendix A), which can be helpful to understand how the culture feels. Both the independent scores and the combined ones are important. Because most of the leaders and employees described their cultures as bureaucratic, which is represented by scores on the transactional scale of 7-14, and the transformational scale of -14 to 6, it seems that increasing the transformational component could help increase the satisfaction with their jobs in general. The transformational component, according to Bass (1998) will be affected by exhibiting more transformational behaviors. Considering the means of the job satisfaction scales overall, the only two facets that might benefit from a cultural change are pay and promotion. Bass and Avolio asserted that the moderately transformational culture is the most ideal. Its scores are represented by -14 to 6 on the transformational scale, and 7-14 on the transactional. The mean reported for transformational culture in the current research was near -1 and the mean for transactional was near 9. The scores indicate that the transformational component is very low while the transactional component is slightly high, so the cultures as reported in the current study might be more effective if the transactionals core were reduced and the transformational scores were increased.

What is the relationship between transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership styles, as defined in the MLQ, and organizational culture, as defined in the ODQ?

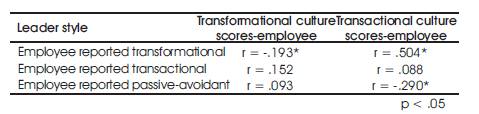

Scores on transformational leadership correlated negatively with transformational culture, and positively with transactional culture (Table 8). This finding is contrary to Bass' (1998) assertion that transformational leaders engender transformational cultures. No correlations existed between the identified leader styles as reported by employees and any of the nine culture styles that were calculated from the combined transformational and transactional scores.

Table 8. Leadership Styles and Culture

Because transformational leadership styles correlated with both culture styles, the analysis supports the directional hypothesis, H 2: A relationship exists between 1 transformational, transactional, or passive-avoidant leadership styles, as measured by the MLQ, and organizational culture, as measured by the ODQ in small animal veterinary hospitals. Using Creswell's (2002) definitions for strength of correlations, the correlation is slight negative between transformational leadership and transformational culture, and moderately positive between transformational leadership and transactional culture.

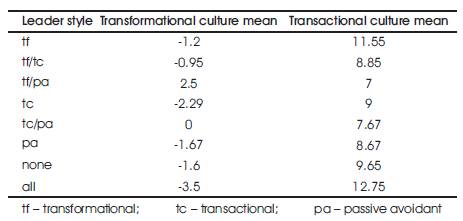

Considering the eight leadership behaviors that include transformational (TF), transformational and transactional (TF/TC), transformational/passive-avoidant (TF/PA), transactional (TC), transactional and passive avoidant (TC/PA), passive-avoidant (PA), no leadership behaviors (none), and all leadership styles (all), the TF/TC style most closely matches the population mean for culture scores of -.60, 8.76 (Table 9).

Table 9. Means of Culture Types for Each Leadership Combination

Most of the leaders in the current research demonstrate the transactional style of leadership according to the raw scores from the MLQ as reported by employees, (Figure 1 and Table 1) but displayed transformational and transactional behaviors (Figure 2). No demographic characteristics correlated with any leadership style. Most of the cultures were bureaucratic (Figures 3 and 4). Employees were more satisfied with transformational leaders than transactional ones when the raw scores were analyzed (Table 4), and the means for job satisfaction were higher for all leadership styles that included transformational (Table 5). No correlations existed between the cumulative culture scores that result in the nine culture styles identified by Bass and Avolio (1992) and leadership styles reported by leaders and employees. However, transformational leadership positively correlated with transactional culture as reported by employees when the raw scores for each type of culture were analyzed (Table 8). Though not specifically identified as a research question, it is important to note that transactional culture positively correlated with all six job satisfaction facets (Table 6). The data analysis, based on a 54% response rate, resulted in the rejection of the null hypotheses H01 and H02. Rather, there is a moderate (Leedy & Ormrod, 2005) correlation between satisfaction with opportunities for promotion and supervisor and transformational leadership. There is slight (Leedy & Ormrod) support for the positive correlation between satisfaction with the work and transformational leadership. There is a moderate (Leedy & Ormrod) negative correlation between passive-avoidant leadership and satisfaction with supervisor, and a slight negative correlation with opportunities for promotion and satisfaction with co-workers. There is a moderate (Leedy & Ormrod,2005) positive correlation between transformational leadership and transactional culture, and a slight (Leedy & Ormrod) negative correlation with transformational culture. There is also a slight negative correlation between passive-avoidant leadership and transactional culture.

The implications of the current research study of leadership and job satisfaction and organizational culture in small animal veterinary hospitals are that most leaders in the study are transactional/transformational (Figure 2), and most employees are satisfied with their supervisors, co-workers and work on the present job, but would like more pay, and more or better opportunities for promotion (Table 2). The employee satisfaction measure for the job in general was 28, which is slightly above neutral (Table 2), suggesting that pay and opportunities for promotion may drive overall satisfaction lower. The analysis of the data also suggests that leadership behaviors that include transformational leadership net the highest overall job satisfaction for employees (Table 5), so leaders' ability and willingness to train to become more transformational could benefit job satisfaction. The cultures of the hospitals as reported by employees were mostly bureaucratic (Figure 4), and could be improved upon with more transformational leadership behaviors and better leader articulation of what is necessary to secure higher pay and meaningful promotions, which are related to particular transactional characteristics. Because no leadership type correlates to satisfaction with pay, and a transactional culture correlated with pay and opportunities for promotion (Table 7), a focus on cultural characteristics that may increase opportunities for promotion and satisfaction with pay may be required. The analysis of the data found that the means for organizational culture as reported by employees were too high on the transactional scale (8.76) and too low on the transformational scale (-.6) (Table 3) compared to what Bass and Avolio (1992) found was ideal. It may be beneficial for leaders to understand better what aspects of transactional culture are beneficial, and how leaders can behave more in a more transformational manner to better balance the transactional culture within their practices.

As in any business, the quality of services a veterinary hospital provides is, at least in part, a result of a financially robust business. It has been established that veterinary hospitals have probably maximized the financial gains that are available through price increases, so continued financial health will be possible mostly through increases in efficiency (Cron et al., 1998) . Efficiency, in part, is accomplished through controlling costs. A balance between the cost of losing an employee and providing satisfactory pay and promotions should be considered to help increase efficiency.

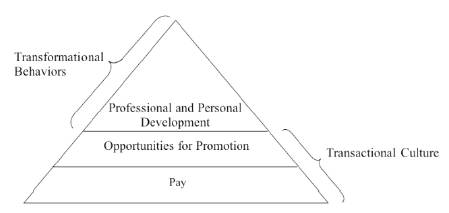

Maslow's Hierarchy (Maslow, 1943) established that individuals have basic needs. The need for food, water, and shelter are most fundamental, and then the need for security comes next. The pay a person receives satisfies these two levels. Maslow's Hierarchy then identifies love, belonging and esteem as the next most important needs.

Opportunities for promotion help satisfy the security, belonging, and esteem needs of an individual, so between pay and promotion, the first four levels of needs that the Hierarchy identifies are met. A transactional culture, which institutionalizes pay through a distinct scale that applies to everyone, and outlines positions and requirements to fill them, will establish the foundation for a satisfied individual as outlined in Maslow's Hierarchy. Leaders who behave in a transformational manner will help employees experience the last two levels of Maslow's Hierarchy through experiencing meaning and purpose in their jobs, and reaching a level of self-actualization where employees feel they are reaching their full potential.

As determined by the means of the job satisfaction scores, promotional opportunities and perception of fair pay appear to be the single most important job satisfaction facets that can be improved in small animal veterinary hospitals by modifications on leadership styles and organizational culture (Table 6). Increasing satisfaction in these areas might help to improve employee's satisfaction with their jobs in general (Balzer, et al., 1997) . The nature of a small animal veterinary hospital concerning opportunities for promotion may be somewhat limited because they are small businesses with little ability to provide upward mobility through the typical hierarchy. Veterinarians must have a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) degree and credentialed technicians undergo some combination of college level schooling and certification. Most others in the hospital have no specific veterinary medical training, nor is it required. Even with this limitation, leaders should think creatively about how tasks and responsibilities may be distributed to allow employees more diversity in their jobs, and attempt to reward them fairly for their work.

A transactional culture positively correlates with employees' satisfaction with their work on the present job, pay, opportunities for promotion, satisfaction with the supervisor, satisfaction with co-workers, and satisfaction with the job in general (Tables 6 and 7). Transformational leadership styles yield the highest satisfaction levels in all facets as well. Both transactional culture and transformational behaviors help satisfaction levels, and transactional culture helps more than transformational behavior in the problem areas of pay and opportunities for promotion as well as satisfaction with the job in general (Table 7). Because outcomes demonstrating satisfaction with pay and opportunities for promotion are low, a focus on improving these facets is important. The means for transactional cultures in the veterinary hospitals studied are higher than the ideal (Bass & Avolio, 1992) , so it is recommended that the leaders improve the institutionalized aspects of a veterinary hospital such as pay and opportunities for promotion, but discourage the negative aspects of transactional culture like focus on short term goals, limitations on employee discretion, and self-interest (Bass & Avolio, 1992) . To moderate the negative aspects of transactional culture, the leader should become more transformational which will help to engender longer-range goals, more employee discretion, and less self-interest. Through training, a leader 's understanding of leader styles and organizational culture aspects will help map the behaviors and focus required to maximize employee satisfaction.

Because the transformational leadership style correlated positively with transactional culture, and negatively with transformational culture, it may be that effective transformational leaders have solidified the important transactional aspects of their culture (Table 8). Transformational leaders exhibit specific characteristics including charisma, stimulation for employees, consideration for employees' needs and wants, and the ability to motivate, however, to be more effective, the leader may need to enhance some of the transactional aspects of the practice's culture.

An important aspect of maximizing employee satisfaction as measured by the Job Descriptive Index (JDI) is institutionalizing pay in veterinary hospitals. A pay scale that is well understood by employees and fairly applied can help in the attempt to institutionalize the pay facet. For instance, the tenure of an employee at the hospital, his or her education level, and previous experience can be rewarded in a point system. Additional points may be earned through assuming new responsibilities, learning new skills, willingness to work full rather than part time, and accessing more continuing education. When the pay system is communicated and adhered to, employees may feel more fairly compensated. It is assumed that they will also understand what is necessary to increase their compensation and promotional opportunities. Once a fair pay scale is implemented along with the requisite promotional opportunities implicit in it, a leader has established a firmer foundation for a satisfied employee as measured by the pay, opportunities for promotion, and job in general facets of the JDI and JIG. The leader's transformational behaviors will add to an employee's satisfaction by helping him or her to develop both personally and professionally.

A conceptualization of these findings is presented (Figure 5). Similar to Maslow's Hierarchy, there is a hierarchy of needs in a veterinary hospital. The transactional culture characteristics that institutionalize pay and opportunities for promotion are fundamental to an employee's satisfaction. When these needs are met, the leader's transformational behavior will enhance an employee's satisfaction by helping him or her to develop professionally and personally.

Figure 5. Model For Leadership Behaviors and Cultural Characteristics Leading to Increased Job Satisfaction

The following leadership terms were derived from the MLQ instrument.

Charismatic/inspirational leadership provides employees with a role model for a vision and ethical standards to live by. The charismatic leader provides a clear sense of purpose (Avolio & Bass, 2004) .

Individualized consideration in leaders is recognized by a development orientation toward followers that encourages them to grow to the followers' fullest potential (Avolio & Bass, 2004) . The last transformational leadership factor is intellectual stimulation, which causes followers to use their imaginations and insights in creative ways, generate new thoughts, and question paradigms (Avolio & Bass) .

A laissez-faire approach is similar, except that the leader does not care what happens in the organizational setting and therefore, does not take responsibility for followers' actions or behaviors (Avolio & Bass, 2004) .

Passive-avoidant leaders may avoid any decisions or, at the very most, take corrective action only after problems have become serious (Avolio & Bass, 2004) .

Transactional leadership is based on reinforcements that are contingent on per formance of followers. Transactional leadership manifests itself in contingent reward, which defines expectations from employees and what will be received in return for performance. Transactional leadership also manifests in active or passive management by exception, which monitors performance and corrects problems when they arise, or does nothing about them at all if the manager is passive (Avolio & Bass, 2004) .

Transformational leadership includes idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Northouse, 2004). Leaders display idealized influence when showing determination, taking risks, engendering a sense of empowerment, displaying a faith in others, and applying creative solutions (Avolio & Bass, 2004).

Organizational culture refers to the shared history of a group that manifests itself through stability, intangibility, and pervasivenes (Schein, 2004) . The ODQ instrument measured two factors, the transformational leadership culture and the transactional leadership culture. The questionnaire contained 24 questions, 12 for each culture type, with the option of a true, false, or undecided response (Parry & Proctor-Thomson, 2001) . Learning about the assumptions that frame employees' views of the culture in which the employee work helped the researcher place the organization in one of nine categories that reflected the level of transactional and transformational behavior within that organization. There is an optimal organizational approach called “ moderately transformational” (Bass, 1998, p. 69) , in which companies tend to operate most effectively.

Nine types of organizational cultures can be defined, according to Bass and Avolio (1992) , and are derived from the ODQ. The coasting organization is balanced between transformational and transactional culture where external and self-controls are equally identified. In a garbage can culture, little leadership exists so there is little consensus or vision. The high-contrast organization is marked by a visionary approach, but also has transactional characteristics. The loosely guided organization has few formal agreements, and the employees are highly independent of each other. External and internal controls are balanced in the loosely guided organization. In a pedestrian culture, the employee will not accomplish tasks without specific instructions to do so, thus avoiding risk. The predominately and moderately bureaucratic organization are two culture types that are internally competitive. Employees work for their own self-interests and rules predominate. The predominately transformational and moderately transformational organizations are two culture types marked by visionary approaches. The culture is not highly dependent on contracts and is not highly dependent on rewards (Bass & Avolio) .