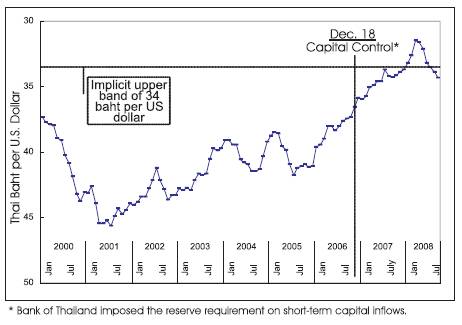

Figure 1. Nominal exchange rates of baht vis-à-vis the US dollar

This empirical study examines the experience of a central bank of a developing country, Bank of Thailand, in operating foreign exchange intervention during the period of persistent appreciation of its currency in 2001-2007. Bank of Thailand has resorted to various tools, specifically foreign exchange intervention of outright spot transactions (buying US dollar/selling Thai baht) and sell/buy swaps (selling US dollar/buying baht spot and buying US dollar/selling baht forward), capital flow management, and sterilization operation to dampen rapid baht appreciation and stabilize its domestic economy. Prolonged foreign exchange intervention results in rapid increases in foreign exchange reserves and forward obligations of US dollar buying, especially during 2006-2007 when the size of intervention is unprecedented. This massive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and net forward position could jeopardize the Bank of Thailand's balance sheet as taking long position in depreciation-prone currency, the US dollar, may incur foreign exchange loss when baht appreciates substantially. In the world of increasing financial integration, mitigating exchange rate volatility at the same time of stabilizing domestic economy has become a great challenge to the monetary authorities of developing countries. The experience of Thailand provides a case study of how a small and open economy manages its exchange rates to contain the risks that come with global capital flows while maintaining internal stability.

Foreign exchange intervention refers to actions undertaken by central bank or monetary authorities of a country in buying and selling foreign currencies with the objective to influence currency movements. The intervention can be conducted in both spot and forward markets with a variety of methods for financing the operation such as foreign exchange reserves, swaps, and borrowing (Baillie, Humpage, & Osterberg, 2000). Even though the frequency of intervention and the number of developed countries that have actively intervened have declined in the last decade, foreign exchange intervention remains an important policy tool in many developing countries for achieving objectives such as influencing the level of exchange rate, dampening exchange rate changes, smoothing exchange rate volatility and accumulating reserves (International Monetary Fund, 2007, p. 32). In the period of increasing exchange rate volatility, particularly those of emerging market economies, in recent decade (Mihaljek, 2005), foreign exchange intervention is frequently employed. As a result, we witness unprecedented increases in foreign exchange reserve accumulation by emerging market economies in recent years. Bank for International Settlements (2005) reports that, between 2001 and 2004, global foreign exchange reserves grow considerably by over US$1,600 billion, mostly by emerging market economies in Asia. Particularly in China, foreign exchange reserves have been accumulated to US$1,530 billion at the end of December 2007 (Goldstein & Lardy, 2008).

Thailand, a small economy in Southeast Asia region, has steadily and increasingly integrated its economy to the global economy both in terms of trade and finance. Since July 2, 1997, the Thai monetary authorities have implemented the managed float foreign exchange system combined with inflation targeting monetary policy framework. As arguing by Eichengreen (2002), “Leaning against the wind in foreign exchange markets is integral to the operation of inflation targeting in open economies and it does not imply benign neglect of the exchange rate”, the Thai monetary authorities do not forgo intervention in foreign exchange markets to influence exchange rate movements. The first objective of this paper is to elucidate the operation of the monetary authorities in managing foreign exchange rate movements during the period of persistent baht appreciation in 2001-2007. The experience of Thailand reveals that the monetary authorities have combined policy actions of foreign exchange intervention, capital flow management and sterilized intervention to dampen the movements of baht/US dollar foreign exchange rates. To lean against the market expectation on baht appreciation, outright spot transaction and sell/buy foreign exchange swap are the monetary instruments used by the Bank of Thailand to intervene in the foreign exchange markets. The supplementary measure of capital flow management such as the stringent measure of Chilean-style capital control in the form of 30% unremunerated reserve requirement is also employed to discourage short-term capital inflows and speculative hot money. In addition, sterilization with a combination of monetary policy instruments: repurchase operations, Bank of Thailand's bonds, and foreign exchange swaps is conducted to mitigate the expansionary effect of the central bank's spot foreign exchange intervention and absorb baht liquidity out of the domestic financial market. The second objective of this paper is to analyze the implications of such foreign exchange intervention for foreign reserve accumulation, forward obligation build-up, and the Bank of Thailand's balance sheet. The experience of Thailand provides a case study of how a small and open economy manages its exchange rate during the period of prolonged baht appreciation. This study provides more understanding on the structure of foreign exchange intervention and gives a basis for future research on intervention by the authorities of developing countries.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 1 examines currency appreciation trend and foreign exchange policy of Thailand, particularly capital flow management on capital inflows and baht speculation. Section 2 analyzes Bank of Thailand's operation on foreign exchange interventions that have occurred in the context of upward pressure on baht. Section 3 discusses the implications of official interventions for foreign exchange reserve accumulation, forward obligations of US dollar buying, and the central bank's balance sheet. Section 4 concludes the paper.

On July 2, 1997, the Thai monetary authorities decided to adopt the managed float foreign exchange system, replacing the exceptionally high US dollar weight basket-of-currencies system that was accused of causing the worst financial crisis in the history of Thailand. Since then, foreign exchange rates of baht vis-à-vis the US dollar are let to be determined by the market forces. Baht is allowed to move in line with changes in country's economic fundamentals and financial development while the central bank intervenes to contain excessive exchange rate volatility. On May 23, 2000, the monetary policy framework of inflation targeting with short-term interest rates as the operating target for keeping core inflation within 0-3.5% was officially announced. With less restriction on capital flows, the monetary authorities employ exchange rate flexibility under the managed float foreign exchange system as external shock absorber while the inflation target is the nominal anchor for domestic monetary policy. Financial Markets Operations Group of the Bank of Thailand (2005) claims that this new policy framework enhances Thailand's monetary policy independence.

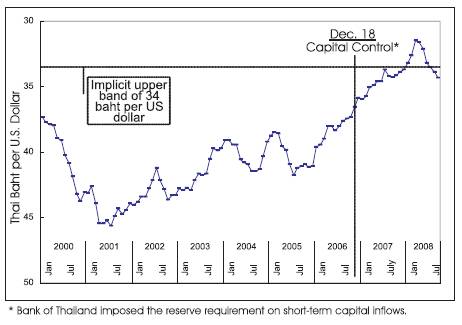

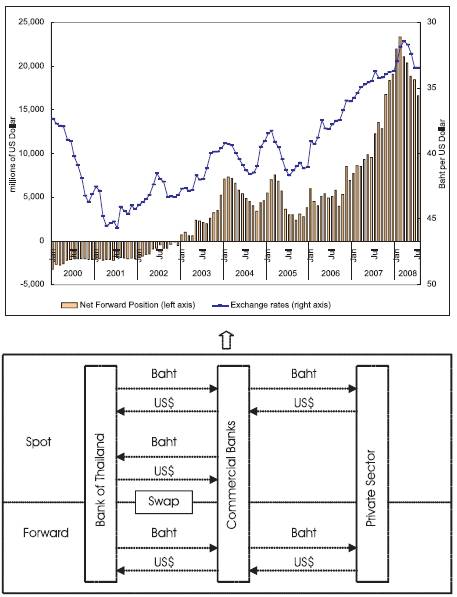

Baht appreciation becomes noticeable in the second half of 2001, as evident in Figure 1. To suppress rapid baht appreciation, Bank of Thailand has largely and actively intervened in the foreign exchange markets. In many occasions, especially during 2006, regulations on capital inflows and baht speculation were strengthened. The central bank made use of capital flow management as a complementary tool to official foreign exchange intervention in order to contain excessive and disorderly movements of baht/US dollar exchange rates. Restrictions on short-term liquidity management were imposed on September 11, 2003 aiming at curbing a surge in speculative capital inflows. Because the measure was not comprehensive with a loophole in nonresident baht accounts (NBRA), stricter measure was announced on October 14, 2003, requiring all domestic financial institutions to limit the total daily outstanding balance of nonresident baht accounts to not exceeding 300 million baht per nonresident. To discourage depositing baht in nonresident baht accounts, financial institutions were prohibited from paying interests on such current and savings accounts. As a result, the outstanding balances of nonresident baht accounts reduced substantially from 63,000 million baht in the first half of October 2003 to 16,000 million baht as of October 16, 2003 (Financial Markets Operations Group, Bank of Thailand, 2005). Nonresidents became less active in the Thai baht foreign exchange markets with a significant decline in the share of nonresident transactions in the markets from 28% during February 1998-August 2003 to 18% during September 2003-October 2004 (Financial Markets Operations Group, Bank of Thailand, 2005).

Baht appreciation moderated in 2004-2005, though excessive exchange rate movements occurred occasionally. Nominal exchange rates of baht vis-à-vis the US dollar fell to 41.50 baht to the US dollar in August 2004 but rose abruptly to 38.48 baht to the US dollar in the first quarter of 2005. Massive foreign capital started flowing into Thailand once again in 2006. It put strong pressures on baht appreciation as evident in a sharp rise of baht/US dollar foreign exchange rates in this period. With the export-led growth development model that Thailand has followed since the 1980s, Thai economy has become highly dependent on exports. Persistent and rapid baht appreciation made Thailand lost its competitiveness in the global market, and consequently had adverse effects on the country's exports and economic growth. Bank of Thailand, therefore, imposed additional measures to moderate capital inflows and safeguard against short-term instability and speculation in the foreign exchange markets. Measures such as controlling baht liquidity to nonresidents without underlying trade and investment in Thailand, and monitoring and seeking cooperation from financial institutions in conducting short-term transactions on foreign exchange, debt securities, and nonresident baht accounts with nonresidents were announced on November 7 and December 4, 2006.

To complement actual interventions in the foreign exchange markets, verbal intervention of the monetary authorities by repeatedly warning the markets that tough measures would be imposed to dampen short-term capital inflows from speculating on Thai baht was used to manipulate market expectation on baht appreciation (The Nation Newspaper, 2006a). Nevertheless, the appreciation trend persisted. There were rumors in the foreign exchange markets that baht would strengthen to 29 to 32 baht to the US dollar (The Nation Newspaper, 2006b), surpassing the implicit upper band of 34 baht to the US dollar (The Nation Newspaper, 2007a, 2007b). As exchange rate on December 15, 2006 stood at 35.09 baht to the US dollar, the rumors intensified. Finally, on December 18, 2006, the stringent measure of a Chilean-style capital control in the form of 30% unremunerated reserve requirement was imposed on all capital inflows that exceed US$20,000 with the exemption of foreign exchange transactions that are related to current accounts and foreign direct investment (FDI) (Bank of Thailand, 2006a). The imposition of capital control provoke negative reaction particularly from the stock market. There is an empirical evidence exhibiting the negative abnormal returns around the announcement of the capital control (Vithessonthi & Tongurai, 2008). The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) fell by 14.84% from 730.55 points to 622.14 points in the first day of capital control implementation (December 19, 2006). To regain investors' confidence and calm down the stock market, the Bank of Thailand issued the announcement No.52/2006 on December 22, 2006 to clarify the scope of capital control implementation (Bank of Thailand, 2006b), stipulating clearly that equity investments in the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET), the Thailand Futures Exchange (TFEX) and the Agriculture Futures Exchange of Thailand (AFET) are not subjected to the measure.

The trend of baht appreciation persisted in 2007. Nominal baht/US dollar exchange rates broke the implicit upper band of 34 baht to the US dollar in April 2007. By December 2007, the value of baht had appreciated to 33.70 baht to the US dollar, an appreciation of 5.94% compared to the exchange rate of December last year. Meanwhile, severe public criticism on the capital control measure announced on December 18, 2006 has shifted the Bank of Thailand's policy stance toward more liberalization, as witnessed in key policy announcements in 2007 (29 January, 1 March, and 17 December) in Figure 1. After six weeks of capital control implementation, the option of foreign exchange hedging is allowed to reduce financial costs and increase flexibility in doing businesses of the private sector. After relaxing capital control gradually throughout 2007, the abolishment of Chilean-style capital control was officially announced on February 29, 2008, ending the episode of control on capital inflows in Thailand (Bank of Thailand, 2008). By the time the capital control was revoked, baht/US dollar exchange rate had reached 31.46 baht to the US dollar, 2.54 baht above the implicit upper band. In summary, the trend of baht appreciation is very prominent. It has persisted throughout July 2001-March 2008. Thai baht has strengthened from 45.62 baht to the US dollar in July 2001 to 31.46 baht to the US dollar in March 2008, an appreciation of over 31%.

Figure 1. Nominal exchange rates of baht vis-à-vis the US dollar

Other Asian emerging economies often combine foreign exchange intervention with capital controls (e.g. Indonesia and Malaysia), prudential regulations (e.g. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Korea) or other rules (e.g. foreign currency surrender requirements) for stabilizing their foreign exchange rates as it is commonly viewed by central bankers that capital controls and foreign exchange regulations enhance the effectiveness of foreign exchange intervention (Mihaljek, 2005). In line with the operation in foreign exchange intervention of other developing countries' central banks, Bank of Thailand has actively and continuously intervened in the foreign exchange markets and in many occasions has implemented stricter regulations on capital inflows to suppress rapid baht appreciation during 2001-2008. The foreign exchange intervention of the Bank of Thailand nevertheless is less transparent as neither intervention strategy nor information on actual intervention is published or disclosed to the public (Moser-Boehm, 2005).

In response to the market expectation on baht appreciation, private sector normally enters into forward contracts with commercial banks, the authorized exchange dealers, to sell their foreign currency receivables so as to manage transaction exposure of their income streams. Meanwhile, their foreign currency payables are usually left unhedged because baht appreciation would lessen the burden of their foreign currency payments. The net position of selling US dollar forward by Thai exporters has increased rapidly from US$4,500 million in January 2006 to US$23,000 million in March 2008 while the net position of buying US dollar forward by Thai importers has increased only slightly from US$4,000 million in January 2006 to US$5,000 million in March 2008 (Waiquamdee, 2008). With high return on investment in Thai financial assets (for example, the average return on investment in 30 days treasury-bill rate in 2006 was 5.62%) and additional profit derived from baht appreciation when funds are repatriated, foreign investors usually hold the net position of selling US dollar spot without hedging their repatriated funds by entering into forward contracts of buying US dollar. Such response would intensify the market pressure on baht appreciation in the spot foreign exchange markets. To gain dear profits, the normal practice of speculators is to take uncovered long position in appreciation-prone currency, in this case is Thai baht. Speculation arises in the forward foreign exchange markets as speculators enter into forward contracts of selling US dollar/buying baht. If baht appreciates at the maturity date of forward contracts, speculators will earn easy profits by delivering US dollar in exchange for Thai baht with their forward contracts and then selling baht in the spot foreign exchange market where the baht/US dollar foreign exchange rate is stronger. Because of this profit making strategy, the net position of speculators in response to baht appreciation would be selling US dollar forward, which is equivalent to buying baht forward.

The aforementioned responses of the private sector to the expectation on baht appreciation create pressures of baht buying in both spot and forward foreign exchange markets. Commercial banks, being the counterparties of private sector in foreign exchange transactions, thus hold the opposite foreign exchange position. They have long position in depreciation-prone currency, the US dollar, and short position in appreciation-prone currency, Thai baht. Such foreign exchange positions would incur loss to commercial banks when baht appreciates. Commercial banks usually cover open position of their foreign exchange transactions to eliminate foreign exchange risk. To cover long position in US dollar of spot foreign exchange transactions, commercial banks sell US dollar in the spot foreign exchange market. As standard practice to balance the long forward position in the depreciation-prone currency, commercial banks cover their exchange risk exposures by selling US dollar spot. Through banks' covering operation, the pressure of baht appreciation in the forward foreign exchange market would intensify the pressure of baht appreciation that is already overwhelming in the spot foreign exchange market. Nevertheless, the maturity mismatch is left to be managed as commercial banks' forward obligations of buying US dollar from the private sector must be fulfilled at the maturity date of forward contracts.

Two means are available to cover both foreign exchange exposure and maturity mismatch of commercial banks' forward foreign exchange contracts. First, commercial banks would resort to interbank market by borrowing US dollar from the interbank market, converting it into Thai baht in the spot foreign exchange market (covering operation for foreign exchange risk), and re-lending baht in the interbank market for the period matching the maturity of forward foreign exchange contracts (covering operation for maturity mismatch). At the maturity date, commercial banks would get baht from their loan contracts, use it to fulfill their forward foreign exchange obligations with the private sector, and receive US dollar in return to repay their US dollar borrowings. This method of covering operation was not cost effective considering interest differentials of 1-month BIBOR (Bangkok Interbank Offered Rate) and 1-month LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) that were negative in almost all periods during June 2004 January 2008, with the exception being April 2006. With negative differentials of BIBOR and LIBOR rates, interest revenues from lending baht would not cover interest payments of US dollar loans. If the monetary authorities did not conduct sterilized intervention, the effect of borrowing US dollar/lending baht of commercial banks would increase the supply of baht in the interbank market, and subsequently reduce interest rates of baht loans relative to US dollar loans even further. Therefore, resorting to interbank market to cover foreign exchange risk and maturity mismatch was not beneficial to commercial banks during the period of prolonged baht appreciation in 2001-2008.

The second mean for covering foreign exchange risk and maturity mismatch of commercial banks' forward obligations is to use foreign exchange swaps. By entering into buy/sell swaps (buying US dollar spot/ selling US dollar forward), the spot transaction of swaps would provide commercial banks US dollar credits to buy baht spot (covering operation for foreign exchange risk) and the forward transaction of swaps would guarantee commercial banks that they would have baht at the time the forward contracts become due. In the absence of official intervention, this banks' covering operation would result in rising forward premium of baht or increasing forward discount of US dollar. Subject to the market mechanism, forward premium of baht would increase until it reaches the level at which sufficient arbitrage funds are available to provide the counterparty for baht buying. Nevertheless, wider forward premium of baht usually has a repercussion in intensifying the market expectation on baht appreciation. The Bank of Thailand has thus intervened and become the counterparty of commercial banks' foreign exchange swaps. To lean against the market expectation on baht appreciation, Bank of Thailand has intervened in the spot foreign exchange market by buying US dollar/selling baht to suppress the rising of spot baht/US dollar exchange rates. It has at the same time intervened through sell/buy swaps (selling US dollar spot/ buying US dollar forward) to sterilize its spot foreign exchange intervention and absorb baht liquidity out of the domestic financial market. The Bank of Thailand's spot transaction of swaps (selling US dollar/ buying baht) offset its spot intervention (buying US dollar/ selling baht). The net effect of official intervention is the Bank of Thailand's forward obligations of buying US dollar, implying that the central bank itself has taken foreign exchange risk by holding uncovered long position in depreciation-prone currency, the US dollar.

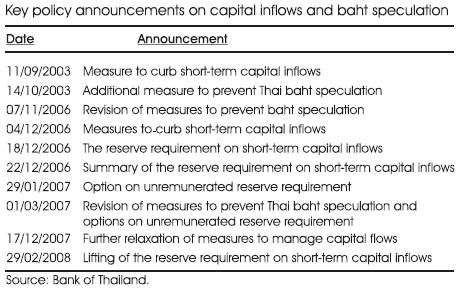

Bank of Thailand's foreign exchange intervention during the period of prolonged appreciation pressures on Thai baht has been conducted through outright spot transactions of selling baht against the US dollar and sell/buy swaps. A survey of IMF (2007) confirms that the Thai monetary authorities have increasingly used forwards and swaps for both outright intervention and sterilization in the period under study (May 2000-June 2007). The use of such intervention tools conforms to other central banks' practices (Neely, 2000; Canales-Kriljenko & Karacadag, 2003; Archer, 2005). Nevertheless, protracted foreign exchange intervention to suppress appreciation pressures on Thai baht has significant implications for foreign exchange reserves, forward obligations, and the Bank of Thailand's balance sheet. With intensified pressures on baht appreciation in the spot foreign exchange market that the Bank of Thailand counteracted by outright spot intervention of US dollar buying/ baht selling, as illustrated in the lower diagram of Figure 2, foreign exchange reserves at the Bank of Thailand have increased sharply from the pre-crisis level of US$38.65 billion to US$107.35 billion as of March 2008. As evident in the chart of Figure 2, foreign exchange reserves of Thailand have increased by US$34.61 billion during 2006-2007 interventions, in which the frequency and volume of foreign exchange intervention occurred at unprecedented level. The Bank of Thailand's spot foreign exchange intervention has repercussions on the domestic economy as baht supply has been injected into the domestic money market. With no sterilized operation, increasing baht liquidity would lower domestic interest rates, reducing incentive for capital inflows and lessening pressure on baht appreciation. Considering the economic situation of rising inflation at that time, falling interest rates would have negative impacts on domestic price stability. The Bank of Thailand therefore sterilized the expansionary impact of its spot foreign exchange intervention.

Figure 2. Foreign exchange reserves at the Bank of Thailand

In addition to the open market operation of selling domestic financial assets (such as Bank of Thailand's bonds and repurchase agreements) to commercial banks to absorb baht supply and make the monetary base remained constant, sell/buy foreign exchange swap has also been a significant tool in conducting sterilization. With spot transaction of foreign exchange swaps, Bank of Thailand could moderate the effects of increasing baht liquidity, as elucidated in the lower diagram of Figure 3. The spot transaction of swaps (selling US dollar/buying baht) offsets the Bank of Thailand's spot foreign exchange intervention (buying US dollar/selling baht), thus baht liquidity has been absorbed from the domestic money market. Forward transaction of swaps (buying US dollar/selling baht) results in a rapid increase in the Bank of Thailand's net forward position of buying US dollar/selling baht, as seen in the above chart of Figure 3. Net forward position has changed from selling US dollar forward to buying US dollar forward since January 2003. It has been accumulated rapidly during 2007 before reaching the highest level of US$23.32 billion in February 2008.

Figure 3. Net Forward Position of the Bank of Thailand

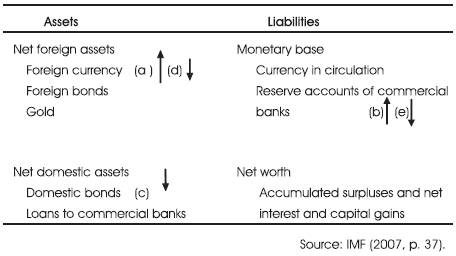

Such sterilized intervention in the foreign exchange markets during the period of baht appreciation has significant implications for balance sheet of the Bank of Thailand. Figure 4 illustrates the effects of foreign exchange intervention on the central bank's balance sheet. Spot foreign exchange intervention of selling baht against the US dollar causes an increase in foreign currency in the central bank's net foreign assets holdings, as indicated by an upward arrow in (a). As intervention is normally conducted through commercial banks, the central bank credits reserve accounts of commercial banks and thus increases the monetary base of domestic money supply (an upward arrow in (b)). Bank of Thailand's spot foreign exchange intervention affects the money supply and interest rates through a change in its holdings of foreign assets. This expansionary impact of spot foreign exchange intervention has been sterilized partly by selling domestic bonds to commercial banks (a downward arrow in (c)) and partly by foreign exchange swaps (a downward arrow in (d) indicates the effect of the spot transaction of foreign exchange swaps of buying baht against the US dollar). The sterilization has absorbed the baht liquidity associated with the spot foreign exchange intervention and made the monetary base unchanged (a downward arrow in (e)). Whereas the sterilization through open market operation changes the composition of the central bank's assets to higher net foreign assets (foreign currency) and lower net domestic assets (domestic bonds), the sterilization through foreign exchange swaps has no immediate impact on the central bank's liabilities as forward transaction of selling baht/ buying US dollar is the off-balance-sheet item that will be settled at a future date. This forward obligation will affect the central bank's balance sheet when it is settled. Settlement of the forward transaction of foreign exchange swaps (selling baht/ buying US dollar) would increase foreign currency in the central bank's net foreign assets holdings and increase the monetary base by increasing reserve accounts of commercial banks (as in the case of unsterilized intervention). Unless there is another offsetting transaction (e.g. the forward contract is rolled over), foreign exchange intervention by swaps can only delay the impact on increasing foreign exchange reserves and rising monetary base. With persistent baht appreciation during 2001-2007, sterilized intervention by foreign exchange swaps has expanded the Bank of Thailand's forward obligations, as evident in Figure 3.

Figure 4. Central bank stylized balance sheet

Prolonged sterilized intervention could jeopardize balance sheet of the Bank of Thailand. Because securities used in sterilization through open market operation are mostly short-term bills (100 percent of Bank of Thailand's bonds as of end 2004 are short-term bonds with maturity of six-months to one-year), it exposes the central bank to rollover risks and rising future costs should domestic interest rates rise (Mohanty & Turner, 2005). The central bank issues short-term obligations to acquire foreign exchange reserves holding. Even though a high level of foreign exchange reserves supports a confidence in the currency and helps reduce external vulnerability and sovereign risk, holding large amount of foreign exchange reserves may incur losses to the Bank of Thailand if baht appreciates substantially. The Bank of Thailand's long position in the depreciation-prone currency, the US dollar, has incurred accounting loss when foreign exchange reserves are valued in Thai baht. As baht appreciates substantially, such loss in 2005 is reported to be as high as 174 billion baht or 2.2% of GDP (Bank of Thailand, 2007).

This empirical study examines the experience of a central bank of a developing country in managing foreign exchange rate movements during the period of currency appreciation. From the case study of Thailand, we identify that the central bank's operation employs a combination of foreign exchange intervention, sterilization, and capital flow management to moderate rapid baht appreciation and sustain domestic interest rates to control inflation. In responses to the market expectation on baht appreciation, the private sector normally holds long position on appreciation-prone currency, Thai baht. The reactions create pressures of baht buying in both spot and forward foreign exchange markets. The Bank of Thailand's intervention in the spot foreign exchange markets by buying US dollar/selling baht creates an expansionary monetary impact as baht supply is injected into the domestic money market. Adhering to the goal of price stability under inflation targeting framework and the domestic economic situation of rising inflation, Bank of Thailand has sterilized monetary impact of its spot foreign exchange intervention. Sell/buy foreign exchange swap (selling US dollar spot/buying US dollar forward) is a significant tool that the central bank employs for conducting sterilization to absorb baht liquidity. Spot transaction of the Bank of Thailand's swaps (selling US dollar/buying baht) offsets its spot foreign exchange intervention (buying US dollar/selling baht). As a result, baht liquidity is absorbed from the domestic money market. Meanwhile, its forward transaction of swaps (buying US dollar/selling baht) is equivalent to the Bank of Thailand's taking uncovered long forward position in the depreciation prone currency, the US dollar. Prolonged foreign exchange intervention to suppress appreciation pressures on Thai baht has significant implications for foreign exchange reserves, forward obligations, and the central bank's balance sheet. The Bank of Thailand's foreign exchange intervention results in rapid increases in foreign exchange reserves and forward obligations of US dollar buying, especially during 2006-2007 when the size of intervention is unprecedented. Such sterilized intervention could jeopardize the Bank of Thailand's balance sheet. As securities used in sterilization through open market operation are mostly short-term bills, Bank of Thailand is exposed to rollover risks and rising future costs should domestic interest rates rise. In addition, holding large amount of foreign exchange reserves may incur losses to the Bank of Thailand if baht appreciates substantially.

With limited literature on the foreign exchange intervention operated by central banks of developing countries, this study adds up empirical research on the issue. In the world of increasing financial integration, mitigating exchange rate volatility at the same time of stabilizing domestic economy has become a great challenge to the monetary authorities of developing countries. The experience of Thailand provides a case study of how a small and open economy manages its exchange rates and internal stability to contain the risks that come with international capital flows.