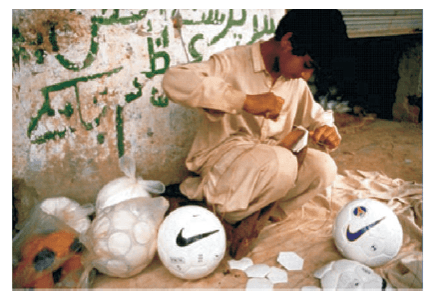

Figure 1. In 1995, Life Magazine Released this Photo of a Child Making a Nike Football in Pakistan. This Image Created a Public Outcry

This study examines the awareness of industrial designers and consumers to ethical issues related to product design. It also explores the impact ethics has on consumer behaviour and the design process. Two separate questionnaires were conducted with consumers and industrial designers from the United Kingdom. An interview was also conducted with Dr. Monika Hestad, an expert in the interaction between branding and product design.

The results of the study indicate that those engaged in the practice of industrial design are more aware of ethical issues than consumers and interpret ethical issues in a more favourable manner. It also highlights that people have biases towards brands and that the biggest criteria to overlooking ethical issues is the product price. It was also found that industrial designers believe that ethics are important consideration in the design process for which they feel a responsibility to uphold and educate others.

This paper discusses ethical responsibility throughout the product lifecycle and suggests methods in which designers can act more ethically and the scope they have to make a positive impact in a world where ethics are becoming increasingly adopted by companies as a core value.

It has become increasingly important for companies to be value driven as the perception of their role in society changes and information on company behaviour is more readily available (Hestad, 2013). In 1970, Economist Milton Friedman stated that a company's only social responsibility was to make a profit and this impacted the mentality of many companies at the time (Friedman, 1970). Today however, companies are increasing value driven, taking into account their social impact alongside the motive to make profit.

Designers have great potential in their role, to influence the future world we live in. It is therefore important that designers are aware of ethical issues in design so that they can act ethically and honestly to drive companies in a meaningful direction. Designers create products that people purchase and experience and one can influence how people view the world and engage in their everyday lives as well as how companies engage in business.

This research is being conducted to provide an overview on the awareness and opinion of consumers and designers towards ethical issues to suggest differences in the mindset of both groups. It aims to provide a better understanding of how ethics influences consumer behaviour as well as how designers view and engage with ethical issues in the design process. Finally, the research aims to suggest practical and realistic ways in which designers can approach design in a more ethical manner.

To access designer and consumer awareness of unethical products; how this affects product design and consumer buying behaviour.

(i) Do consumers and industrial designers share the same level of awareness of these issues?

(ii) How does age and socio-economic status influence awareness?

(i) Do consumers and industrial designers view ethical issues in the same way?

(ii) How important are these issues to consumers and are some ethical issues more important than others?

(iii) Do consumer reactions to unethical behaviour differ depending upon the product and brand?

(iv) What conditions are needed for consumers to overlook unethical behaviour?

(i) Where is the line between ethical and unethical?

(ii) Is unethical behaviour by companies on the rise or in decline?

(i) What level of responsibility do industrial designers have?

(ii) How can industrial designers combat unethical behaviour?

This paper also aimed to look into the correlation between socio-economic grouping and age towards these respective issues. However due to time constraints, this was not possible and therefore this would be an area of further research.

In the pursuit of increasing market share and maximising profits, multinational corporations will sometimes push the boundaries of what could be considered acceptable behaviour. However, to what extent are consumers aware of these unethical tactics, how does their knowledge of unethical behaviour influence their behaviour and what responsibility do industrial designers have in this process? The term ethics is defined as “moral principles that govern a person's behaviour or the conducting of an activity” (Oxford Dictionary, 2016a) and in this context, will refer to the actions of multinational corporations in regards to greenwashing, planned obsolescence and the exploitation of manufacturing labour.

Greenwashing is defined as “ the disinformation disseminated by an organisation so as to present an environmentally responsible public image” (Oxford Dictionary, 2016b). An example of greenwashing that has recently brought the public attention is Volkswagen who admitted to “fitting cars with software designed to give false readings in emission tests” (Bloomberg, 2015).

A 2010 report from the marketing firm ‘TerraChoice’ categorises different aspects of greenwashing into what they call the “seven sins” and highlighted that there is currently limited regulation on such issues. This ranges from the “sin of vagueness” to the “sin of no proof” (TerraChoice, 2010). However, critics like sustainable business author Joel Makower, argue that greenwashing is the teething effect of the new green market rather than the intentional manipulation of consumers, and that these claims show that companies understand the importance of going green (GreenBiz, 2008).

Research conducted into the effects of green advertising on US student consumer attitudes concluded that “consumer perceptions of greenwashing are real and their impact on brand attitudes and purchase intent is significant” and that some industries are more prone to scepticism surrounding green claims than others (Nyilasy, et al., 2014). The focus of this study needs to be broadened to different consumer demographics as it could be that students are more aware of environmental issues.

In an effort to minimise manufacturing costs, it is common for companies to outsource production to low wage countries. In 1996, Nike became infamous for its exploitative manufacturing practices including paying children $0.06 an hour to stitch footballs (Labor Rights, 2016) (Figure 1). Nike's chairman, Philip Knight admitted “The Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime, and arbitrary abuse” (Herbert, 1998). Stock prices and sales fell which Knight claims that it was due to consumer preferences shifts in the Asian market. However from 1994 to 1998 in the midst of the labour exploitation controversy, sales increased from to $3.8bn to $9.6bn (Labor Rights, 2016) showing that it had little impact, despite a study indicating that consumers place a strong dislike on child labour relative to other ethical factors (Auger, et al., 2003).

Figure 1. In 1995, Life Magazine Released this Photo of a Child Making a Nike Football in Pakistan. This Image Created a Public Outcry

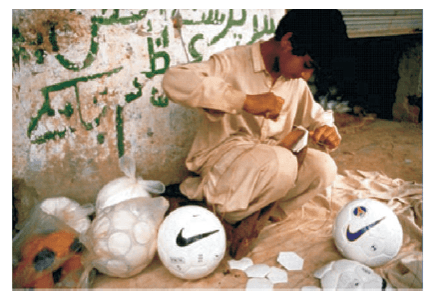

In 2010 it was reported that 14 workers at Apple's largest contractors, Foxconn, had committed suicide due to working conditions (Bloomberg, 2015) (Figure 2). This also had minimal impact over the stock price and sales of the soon to be released iPhone 4, indicating that maybe some products are too compelling to be influenced by negative ethics.

Figure 2. After 14 Workers Committed Suicide at Foxconn, the Company Erected more than 3 Million Square Meters of Mesh ting to Catch Suicide Jumpers

Planned obsolescence is defined as “a policy of producing consumer goods that rapidly become obsolete and so require replacing” (Oxford Dictionary, 2016c), this is to encourage the future purchase of new products and services in the future by consumers to replace outdated ones. In the technology industry, critics like Don Norman argue that companies such as Apple are guilty of planned obsolescence by systematically releasing features in a way to make users feel the need to constantly buy newer versions (Bilton, 2012). One example of this is the omission of a camera on the first iPad although some would say that this was due to performance. The use of tamper-resistant screws and a fixed battery with a $79 cost to replace can be seen as encouraging consumers with older phones to consider buying a newer replacement than seeking repair. This excessive consumption has contributed to the volume of e-waste growing three times faster than regular waste polluting the environment of developing countries with toxic chemicals (Vidal, 2013).

Dieter Rams and his design philosophy has impacted many popular designs and designers in today's world. In the late 1970s, Dieter Rams came up with the 10 principles of good design when he was aware of the contribution to the world through design and he wanted to have criteria for what made a good design for what he felt were the important principles for good design. His principles of the 10 principles of good design include, such things as 'good design is honest', 'good design is long-lasting', and 'good design is environmentally friendly'.

In an interview with Rams (Hustwit, 2015) when asked about his design philosophy said “I always strove for things to be sustainable. By that I mean the development of long-lasting products, products that don't age prematurely, which won't become out of style. Products that will remain neutral, that you can live with longer.”

A study (Echegaray, 2014) seeking to understand how product lifetime affects consumer experience found that “product lifetime is far from a product purchasing decision”. The younger generation is displaying shorter lifespan expectations and less concern over product longevity. Finally, the motive for buying new products is when there is a perceived inability for it to communicate social status to others. This study was conducted in the emerging market of Brazil and due to cultural differences, may not be a representative of the UK.

Some companies use strong positive ethics as their unique selling point like Fairphone who market a smartphone which considers the ethical impact across all stages of the design process (Fairphone, 2014). However, studies show that although consumers are becoming more ethically minded, these shoppers rarely buy ethical products (Carrington, et al., 2010).

Two questionnaire surveys were implemented and distributed online as well as offline in paper format. The inclusion criteria for both questionnaires were that participants were from the United Kingdom and were over the age of 18. Limiting the questionnaire to participants from the United Kingdom accounts for cultural differences towards ethical issues and is more representative of western culture. The questionnaires were also targeted at two separate respective groups, the first group being consumers with no experience of industrial design, and the second being industrial designers, both students and professional. The questions contained within the questionnaire were identical, however additional questions were included in the questionnaire targeted at industrial designers which focused on ethical issues in the design process. Sharing identical questions across questionnaires allowed for responses to be compared across the two groups. The questions gained qualitative data on the awareness people have of ethical issues relating to industrial design and their perspectives on these. Questions also examined how ethics affects their consumerist behaviour. The additional section in the questionnaire for industrial designers examined ethical issues in the design process. Questions were also included that enabled data comparison between age, gender, socio-economic backgrounds, and design experience. Questionnaires were identified as a suitable research method due to the efficiency of questioning a large amount of individuals and the ease of analysing results to generate insights (Technische, H. D., 2013). The results of the questionnaire were analysed and presented in a visual format.

A semi-structured interview with a duration of one hour was conducted with the branding expert Dr. Monika Hestad, who was chosen due to her extensive research and experience into the interaction between branding and product design. Hestad is the author of the book 'Branding and Product Design: An Integrated Perspective' which has been referenced throughout this paper. She has a master’s degree in Industrial Design from the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and a PhD from the same institution in which she investigated the product designer's role in brand building. She has experience of branding and design relating to a range of industries as well as consultancy work, setting up her first consultancy in 2003 and her most recent in 2012. Hestad was a member of the governmental commission that drafted the Norwegian Higher Education Act 2005 and is an Associate Lecturer at Central St. Martins, London and well teaching management in numerous different countries. The topics covered in the interview included consumer psychology, business and consumer trends, brand loyalty, responsibility of ethics, the power of designers, and disruptive innovation among others.

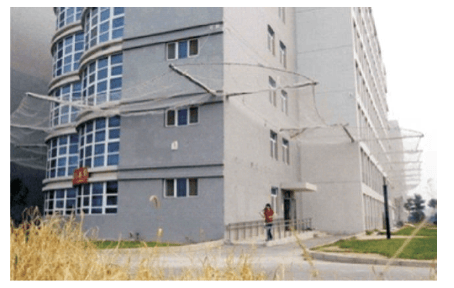

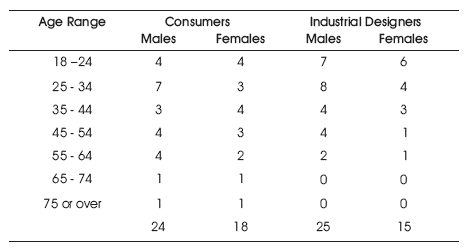

In total, there were 42 individual respondents for the questionnaire targeted at consumers and 40 respondents for the questionnaire targeted at industrial designers. The demographics of the respondents can be seen in Table 1. The representation of respondents over 65 years or older for consumers is minimal and thus the data is not suitable for comparison of this age group to others.

Table 1. Demographics of Respondents across both Questionnaires

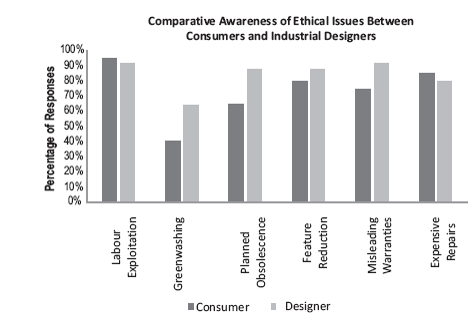

As seen in Figure 3, industrial designers are more aware of 4 of the 6 ethical issues. The ethical issue that industrial designers were aware of is misleading warranties and labour exploitation with 92% of respondents reporting to be aware of this issue. This can be compared to greenwashing which only 64% of respondents were aware of. Consumers in comparison are most aware of labour exploitation at a slightly higher rate than designers at 95%, however only 40% of respondents are aware of greenwashing. The biggest difference in awareness was with greenwashing with a difference of 24%.

Figure 3. Graph Showing the Level of Awareness of Consumers and Industrial Designers towards Ethical Issues

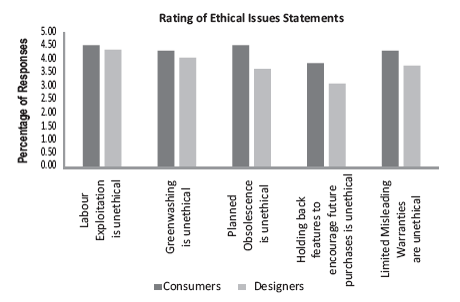

Figure 4 indicates that industrial designers perceive the ethical topics more favourably than consumers. The range of individual responses spans the whole range of strongly disagree (1.00) to strongly agree (5.00). Labour exploitation is unethical which received the highest agreement rating of 4.41 from designers and 4.60 from designers, respectively. The ethical statement with the lowest agreement rating was also shared by both designers and consumers, giving the statement 'holding back on features to encourage future purchases is unethical' an agreement rating of 3.15 for designers and 3.90 consumers, respectively. The biggest disparity in opinions was regarding planned obsolescence with a difference of 0.89.

Figure 4. Graph Showing the Rating of Ethical Topics on a Scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being Strongly Disagree and 5 being Strongly Agree

The survey also asked the respondents to show their level of agreement with certain statements. A scale of 1 to 5 has been used to represent the level of agreement, with 5 representing strong agreement with the statement, 3 representing a neutral agreement and 1 representing a strong disagreement.

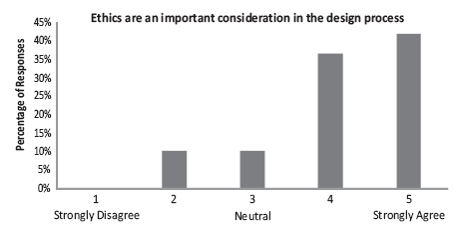

Figure 5 shows how much the respondents agree with the statement of “ethics are an important consideration in the design process”. In total, 0% of the respondents strongly disagreed with the statement, and the majority agreed with the statement, with 42% strongly agreeing and 37% selected ‘agree’. Only 11% selected ‘disagree’, and 11% had a neutral agreement.

Figure 5. Graph Showing How Important Industrial Designers Consider Ethics in the Design Process

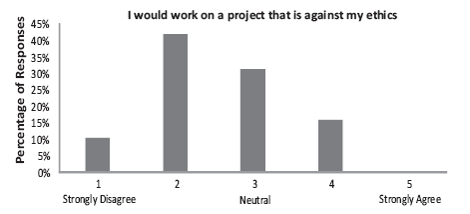

Figure 6 looks at the level of agreement with the statement “I would work on a project that is against my ethics”. None of the respondents strongly agreed with this statement, however only 11% strongly disagreed with the statement and 16% agreed with the statement, selecting agree. The majority of the respondents selected disagree or neutral, with 42% and 32% of the responses, respectively.

Figure 6. Graph Showing the Level of Agreement that Designers have towards Working on a Project that is against their Ethics

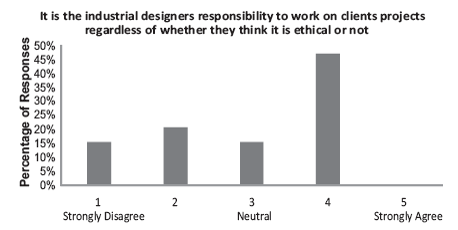

As shown by Figure 7, 47% of the respondents believed that it is the industrial designers’ responsibility to work on a client's project, regardless of whether they thought it was ethical or not. However, none of the respondents strongly agreed with this statement. The majority of the respondents felt neutral or disagreed with this statement, with 53% selecting an agreement level 3 or lower.

Figure 7. Graph Showing the Level of Agreement that Designers have that Clients Should Work on a Project Regardless of their Ethical Stance

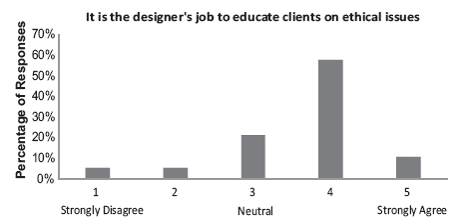

Figure 8 looks at the statement “it is the designer's job to educate clients on ethical issues”. 10% of respondents selected disagree or strongly disagreed. The majority of the respondents agreed with this statement, with 58% selecting agree and 11% selecting strongly agree.

Figure 8. Graph Showing the Agreement of Designers that it is their Responsibility to Educate Clients on Ethical Issues

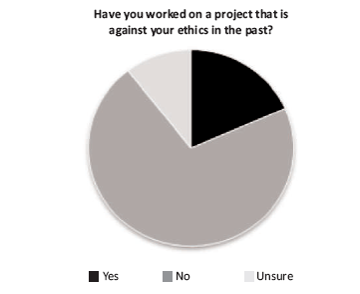

Figure 9 is a pie chart showing the percentage of people who answered yes, no or unsure to the following statement: “Have you worked on a project that is against your ethics in the past?” In total, 71% of the respondents have not worked on such a project, 18% have and 11% are unsure.

Figure 9. A Pie Chart Showing the Percentage of Designers to Work on Projects that have been against their Ethics

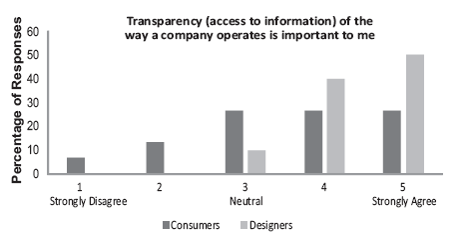

Figure 10 shows how much consumers and designers agree with the statement “transparency of the way a company operates is important to me”. It has been assumed that the responses from the designers can be related to both buying from a company and working for a company, whereas consumers look at just buying from companies. For both groups, the majority of respondents agreed with this statement, and no designers disagreed with the statement. 50% of designers strongly agreed with the statement, whereas 26.67% of consumers selected the same response. 26.67% of consumers also selected agree or neutral, and 13.33% disagreed and 6.67% strongly disagreed (See Figures 11, 12, 13 14, 15, and 16).

Figure 10. Graph Showing the Level of Agreement that Consumers and Designers have that Transparency of a Company is Important

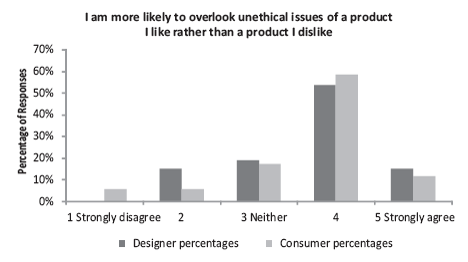

Figure 11. Graph Showing the Agreement Rating of Designers and Consumers to the Statement that they would be more likely to overlook Unethical Issues from a Brand they like Compared to one they disliked

Figure 12. Graph Showing the Agreement Rating of Designers and Consumers to the Statement that they would be more likely to overlook Unethical Issues from a Product they like Compared to one they disliked

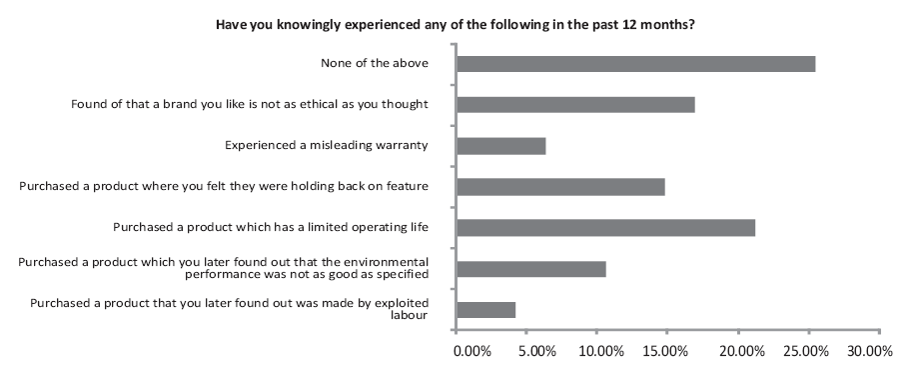

Figure 13. Graph Showing the Percentage of Respondents to have Experienced Unethical Behaviour by a Company in the Last 12 Months

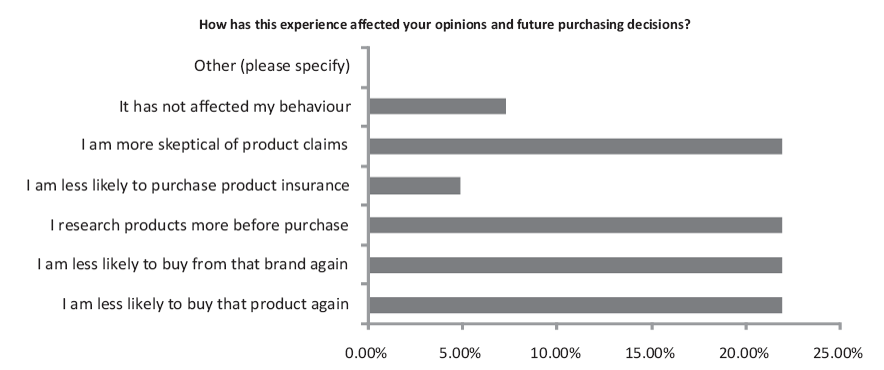

Figure 14. Graph Showing Consumer Reaction of those who Experienced Unethical Behaviour by a Company in the Last 12 Months

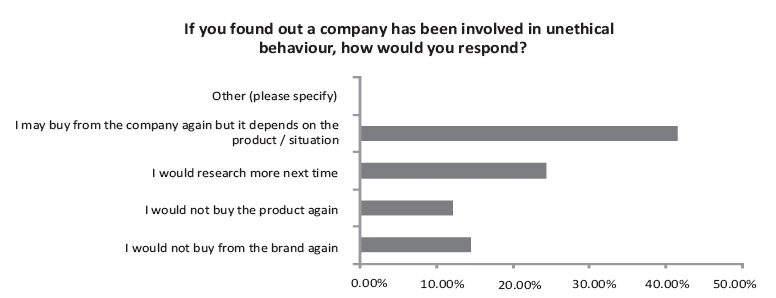

Figure 15. Graph Showing Proposed Consumer Reaction if they were to Find Out a Company had Behaved in an Unethical Manner

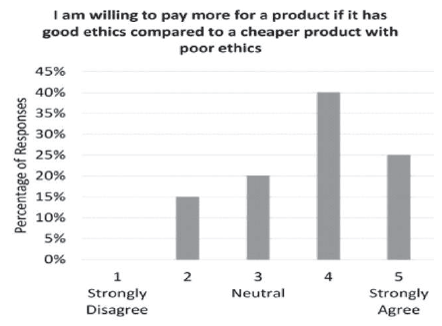

Figure 16. Table Showing the Percentage of Consumers willing to Pay Extra for a Product if it has Good Ethics

It should be considered when interpreting the results that due to the topic of this study, the outcome may be influenced by social desirability bias where respondents have a tendency to answer questions in a more socially acceptable manner compared to their real behaviour. This is most prominent regarding self-reported behaviour such as the extent to which a respondent would pay more for ethical products than non-ethical products. It is also seen that females are more prone to social desirability bias responses than males (Dalton & Ortegren, 2011). The effects of social desirability bias have been minimised though the use of an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire survey

Figure 3 data shows that overall, industrial designers are more aware of ethical issues than consumers. The reason for this being that industrial designers are more educated on topics relating to product design and they will discover and engage in ethical topics while in education or working on professional projects. The high awareness rate of labour exploitation can be explained due to the fact that it is often publicised through news outlets and therefore in general people are more aware of this issue. It could also be considered surprising that both consumers and industrial designers showed the lowest levels of awareness toward greenwashing due to the increased discussion of environmental issues in both the public and the field of industrial design.

Figure 4 indicates that, industrial designers view the ethical topics in a slightly more favourable perspective than consumers, ranking each individual topic as less unethical. When looking at the overall results between both groups there is a clear consensus that the topics raised are unethical in nature. The fact that industrial designers view the topics in a more favourable perspective could be due to their experiences of the product development process and the nuances involved towards the topics with a more open mind to justifications for certain topics like planned obsolescence and thus they take a less extreme viewpoint than consumers. The most unethical issue was rated as labour exploitation, the reason for this could be due to the fact that this is a more humanitarian ethical issue that one can relate to on a more emotional level than the more product related topics of misleading warranties as an example.

The issue which was rated most favourably by both groups was the holding back of features until the next release. This received a mean rating from designers of 3.15 equating to a neutral stance on the issue. This compares to consumers with a mean rating of 3.90 where 4.00 represents an agreement that the issues are unethical. This might be explained by the awareness of industrial designers that there are potential justifications for this strategy, for example by holding back features if you deem the market to not be potentially ready in the case of new products such as the original iPad and the omission of a camera, or that by holding back features you can extend the product lifespan and therefore continue to keep the product relevant. However, it could be argued that this is unethical as they are encouraging consumers to replace over products with a newer one which maybe could have been marketed all at once, thus increasing revenue from customers and contributing to landfill.

It can be seen that more consideration for expensive products with a mean of 5.2 factors chosen for the inexpensive product category compared to 7.3 for the very expensive product category. This as mentioned in the interview with Hestad is because the consumer is more concerned and will do more research when they are dealing with a high priced product compared with a very inexpensive product which might be more of an impulse purchase.

The top factor chosen for overlooking unethical issues from companies was price. This was most prevalent with consumers from lower socio-economic groups who exhibit less concern for ethical issues as they can't afford to those concerns. This also contrasts with Figure 16 where 65% of consumers and designers said they would be willing to pay extra for an ethical product compared to an unethical and cheaper counterpart. The percentage premium that people would be willing to pay was not discovered and thus this could be an area for future research.

People can make decisions based on their own selfinterests, for example overlooking unethical interests if the price is appealing. They also want to give off an impression to those that they find important in their lives like their friends. We wish to give off values to others and we are as we wish to give off values to others and we are inspired by the preference and values of those we find important to use so we can feel a sense of belonging. That is why people identify strongly with certain brands.

The results of the study show that people have a bias towards brands and products they like, with an average rating of 3.75 with 4.00 being agree that people would be more likely to overlook unethical issues of a product if they like rather than one they dislike. Consumers are also more irrational and emotional when dealing with their preferred brands. “You can see that people are more rational and descriptive if you don't have the brand. Consumers are much more descriptive and focused on the functionality and much more rational in how they argument for the products.” People can also make excuses for brands, with them being more forgiving of brands that they perceive to be good or that they connect with some of their values.

Hestad believes that “if you have developed an attitude and profile that you are more moral or ethical than others then it hurts your brand much more”. Therefore authenticity is important when being ethical. “It needs to be authentic but it shouldn't be designed to be authentic which is a very challenging balance for designers”. This is less of a problem for disposable and inexpensive products. Hestad explains this in the interview, “If you have a poor brand or a fragmented brand and the product is bad then of course, it makes sense as there is nothing to buy into then”. With strong brands there will be customers who are strongly in favour of them and will create a community around the brand that may even make excuses for their behaviour, for example the brand loyalty is seen with ‘Apple’ where they are excused by some consumers for changing their charging cables and contributing to landfill.

Hestad believes that she has noticed a bigger change in companies compared to consumers when it comes to ethical issues. Businesses are adopting ethics as a core value and not something of a secondary consideration. More businesses are emerging with an ethical philosophy and finding success because of this. An example of this is Tom's shoes, a fashion company which donates a pair of shoes to a person in the developing world for every shoe sold. These business models are not only profit driven but value driven.

This type of philosophy is starting to be taught as management literature and in management schools across the world with the next generation of business leaders encouraged to become more value centric. Companies are also proactive in delivering what they think consumers would like and they prepare for this for a competitive advantage.

Hestad explains that there has been a noticeable change amongst both consumers and businesses concerning ethical issues. Consumers have become more critical and sceptical of company marketing as they are more aware of marketing techniques. This change can be attributed to the rise of the internet and there is now a much higher demand for transparency from companies because of this. “I think one of the main pressures that the companies have is the much higher demand for transparency”. It is a rising trend which is most seen in the past 5 years, however it can be a problem for consumers to find out this information and thus it can encourage them to not make the effort. Transparency was rated as important by both consumers and industrial designers as seen in Figure 10. Consumers' wishing for more transparency is something Hestad believes presents a challenge to businesses.

The results of the study show that people place more consideration factors on expensive products than inexpensive products. With expensive products, the consumer is more likely to do more research than an inexpensive product that could be more of an impulse purchase.

It can also be seen that consumers can experience a bias towards brands they like. Hestad explains this “If you have a poor brand or a fragmented brand and the product is bad then of course. It makes sense as there is nothing to buy into then.” “You can see that people are more rational and descriptive if you don't have the brand. Consumers are much more descriptive and focused on the functionality and much more rational in how they argument for the products.”

Many designers responded they have not experienced having to work on a project that is against their ethics. Maybe the question could have been reworded to ask if they have had the opportunity to work on a project that they disagree with. When removing those who responded that they have no design experience outside of university then this increase the percentage of respondents as they had real world professional experience where ethical issues are more of an issue than while studying at university.

The idea that everyone shares responsibility of ethical behaviour is an idea which had strong support from the questionnaire survey participants. Hestad believes that the responsibility of acting ethically is a shared one and that “too simple to blame the companies or the consumers”. Customers are responsible for buying ethically sound products however the consumers do not have a responsibility to know everything about the products you purchase, but they have a responsibility to act on their opinions and be more aware of the decisions they make.

Managers are also important as they set the scope and structures that the designers can operate within. Designers should try and push for change within the company. They have choice over where we decide to work and we can choose companies that reflect their own internal values. The manager has more control than the designer but the designer can try and influence the boundaries and can try to assert his influence on the products that are coming out of the company to make them more ethical. Design teams can identify the stages in the customer journey which can provide highest value or the biggest impact and these could be used to make the product more ethical and build an ethical brand (Hestad, 2013).

Consumers can also engage with the internet and use the access to spreading data to large groups of people. People are looking for reviews online and it has been shown that people trust the reviews of other customers more than big corporations so therefore this reviewing of products online can help. This is something which forces the companies to change and gives the consumer more power. Politicians also have power in setting regulations and other institutions which sets criteria that products have to meet and can stimulate the purchase of more ethically sound products through legislation. The media also has a role with journalism and honest portrayal and awareness of these issues. Hestad explains “you cannot change it all but you can change some small parts, so what are the kind of small parts that you can change based on position and where you are. That's how I see it.”

In this study, the author has looked at how designers and consumers react to certain ethical issues, and how their views towards a company would change if unethical practices were carried out. Issues including greenwashing, planned obsolescence and labour exploitation have been raised, and surveys and interviews have been used to discuss how these issues affect product design.

Industrial designers have more awareness of ethical issues than consumers, and they interpret the ethical topics examined in this research more favourably. Perceptions towards ethical issues differed in conviction however labour exploitation was ranked the most unethical across both target groups. Awareness also differs minimally with age and socio-economic status with the younger generation and those of a higher socio economic status exhibiting a greater awareness.

It was found that the biggest reason to overlook ethics was price. Although there was a general consensus of opinion on the ethical issues studied in this paper as being unethical, when looking at the range of results there were a few polarised opinions suggesting that ethics are subjective in nature and not clearly ethical or unethical, it is dependent upon perspective. Through speaking to Dr. Monika Hestad, it was seen that ethics are increasingly becoming a core value, and this is being taught in business schools across the world, however there will be a delay before this becomes common however as it needs time to process through to students and future management. Finally, the industrial designer plays a role among many other stakeholders in the product development and lifecycle process. There are a range of methods they can take to design more ethically and the results show that there is an interest from designer and a sense of responsibility to do so, especially from the emerging generation.