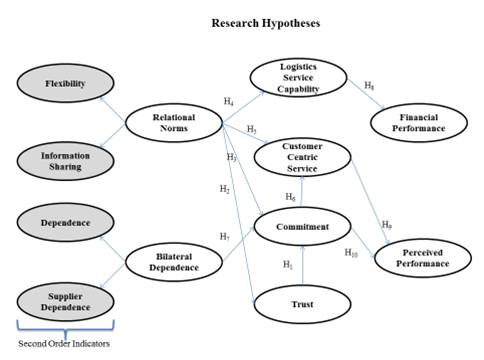

Figure 1. Research Hypothesis

Because an organization's visibility and decision-making abilities in a supply network is limited by its embeddedness, managing the embedded activities may be affected by non-contractual forms of governance and capability. Whatever the organization cannot see, it can't efficiently control. In this paper, the authors have studied non-contractual governance, dependence, and reliance in a manufacturer-vendor dyad in light of logistics, spill-over customer-centric service, and performance. Relational norms (information sharing and flexibility), trust, commitment, and bilateral dependence were hypothesized to explain manufacturers' logistics capability and customer-centric services. Using SEM-PLS (Structural Equation Modeling using Partial Least Squares) approach, all the hypothesized paths were proven with adequate R2 explained for each construct; R2 for financial performance was low.

It is common knowledge among procurement professionals that the percentage quantity of material purchased by manufacturers1 over making them in-house is high enough to deserve consistent managerial attention (Supply Chain Quarterly, 2015 & 2016). Although several research studies have focused on material management issues (e.g., Jap, 2001), limited attention has been paid on manufacturers' logistics that is embedded in this material transfer, which has performance implications for material exchange. Since supply-chain organizations are complex adaptive systems (Mena, Humphries, & Choi, 2013), in this empirical study, the authors have explained manufacturers' adaptiveness through the embeddedness and resource based view (RBV) lens. How improving a manufacturer's overall logistics capability and its customer-centric services with its downstream customers may improve supply-chain performance?

The logistics transaction that is embedded in this material transfer from the vendor to the manufacturer deserve special attention because logistics and customer-centric services may be used as strategic differentiating tools (Skjøtt-Larsen, 2000). To that extent, RBV proponents suggest that the more such resources are valuable, rare, immobile, and non-substitutable, the more an organization's strategic competitive advantage and performance value. These resources include knowledge and capability and organization processes that give it an identity in the market place (Barney, 1991; Sachdev and Merx, 2012). Since a supply-chain solution for each customer's needs is generally situation-specific, complex, and difficult to imitate, any transaction convolution should be identified and understood to avoid loss of sales, profitability, and dissatisfied customers (Tuli, Kohli, & Bharadwaj, 2007).

However, logistics efficiency studies have focused on cost reductions and customer delivery improvements over inept control practices and tension that may lead to the demise of a business (Chen et al., 2015). One of the reasons maybe that such studies are being understood from logistics service providers or their customers’ (shippers) perspective rather than the material buyer's perspective. Furthermore, researchers have pointed out that logistics providers primarily focus their managerial efforts on interpreting contracts, leveraging pricing, and discussing service failures instead of improving the logistic transactions (Halldo’rsson & Skjøtt- Larsen, 2006). Since such material and logistics transactions are on the rise, manufacturers and vendors will need to learn how to improve and sustain themselves in this embeddedness, or face inefficiencies that will defeat the purpose of material exchange.

Embeddedness refers to an organization's dependence and reliance on its supplier and customer in its supply network (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990; Gulati, 1998). However, dependence may only sow the seeds for non-contractual attributes to exist (e.g., relational norms, trust, commitment) rather than having a direct impact on them (Sachdev, Bello, & Verhage, 1995). Hence, it may be interesting to know how dependence and non-contractual governance play out in improving logistics and customer-centric services for this form of embeddedness. Organizations may then reduce committing to wasteful energy in overanalyzing contractual agreements. Had Mattel Toys, Inc. practiced non-contractual governance in improving logistics and customer-centric services, would they have experienced such fallacies (e.g., Wisner, 2011)?

“…Whenever one addresses the supply chain for a particular agent (i.e., a company), one would have to rd specify the referent (e.g., Apple iPod touch, Intel 3 Generation Xeon processor) for that agent as the unit of analysis” (Carter, Rogers, & Choi, 2015, p.91). Marketing channel theorists suggest that clarifying a business exchange from a channel captain's viewpoint (the party that has the expertise and creates the channel) may be an initial step in improving its performance (e.g., Mehta, Dubinsky, & Anderson, 2003). Based on these arguments, the authors study this embeddedness from the manufacturer's perspective (initiators and receivers of the material transaction).

Because an organization's visibility and decision-making abilities in a supply network is limited by its embeddedness (the way the embeddedness under analysis is configured), managing the embedded activities may be affected by non-contractual forms of governance (Mena et al., 2013). Whatever an organization cannot see, it can't efficiently control. Empirical studies or meta-analysis are still needed to explain embeddedness for the different sets of supply-chain configurations and their performance contributions (Choi & Kim, 2008; Carter et al., 2015). If differences in the sets of buyer-seller exchanges are expected, studies should be conducted to determine the necessary managerial adaptations (Kumar, Scheer, & Steenkamp, 1995; Lusch & Brown 1996). Through empirical research, the authors illustrate why interdependency differences exist in a manufacturer-vendor logistics and material transaction, and ways of managing it towards improved performance.

Since the role and position predetermines a manufacturer's structure (power, control, and information flow) in its supply network (e.g., Zafeiropoulou & Koufopoulos, 2013), the authors study non-contractual governance, dependence, and reliance for this embeddedness in light of logistics and customer-centric services (Figure 1). Because of the high frequency of adjustments made to logistics transactions, which are time-based, information sharing and flexibility are two major non-contractual governance discussed in isolated ways in purchasing and logistics (Vickery, Calantone, & Dröge, 1999; Sohail, Bhatnagar, & Sohal, 2006; Fawcett, Calantone, & Smith, 1997). Trust and commitment are the typical forms of reliance among trading partners (Halldo´ rsson & Skjøtt-Larsen, 2006; Zafeiropoulou & Koufopoulos, 2013). In addition, since capability and customer-centric services are necessary contributors to this embeddedness, the authors study these constructs.

Figure 1. Research Hypothesis

The contributions of this research are the following: First, since an organization allocates its resource and capabilities based on its embeddedness, drawing from several research literature, this research flushes the importance of dependence, trust, commitment, and non-contractual governance by integrating these concepts through the eyes of a manufacturer in material and its accompanying logistics transaction. Second, researchers generally sum, subtract, or multiply the individual items of dependence from each side of the dyad to form a composite dependence scale. Based on the objectives of this study, bilateral dependence is measured as a second order construct comprising separate buyer and seller's dependence scores. This second-order approach may better portray the importance of dependence in logistics and material convolution. Third, the authors extend marketing channel literature (Sachdev & Merz, 2012) to material transactions by composing flexibility and information sharing as a second order construct. These actions may reduce the probability of such buyer-seller exchanges to be ineffective or terminated.

To explain these contributions, the theoretical aspects of embeddedness (logistics convolution with material transaction) and RBV are first explored. Next, the hypotheses are developed linking the constructs contained within this embeddedness. Then, the methodology for this study is unfolded. Subsequently, using SEM-PLS, the hypotheses are tested and the results are presented. Finally, the findings and managerial implications are addressed.

The conceptual framework was developed using supply chain literature in line with organization structure behavior- performance, where behavior emanates from an organization's structural embeddedness (e.g., Gulati, 1998). Drawing from the above research studies, the authors treat the manufacturer as the fundamental driver of its network. The network is controlled by adding manufacturing content to the purchased material while considering its spill-over effect with the next set of buyers in the supply network (Jap, 2001). The manufacturer buys the material and implements its logistics activities (e.g. order processing; MRP, DRP) using its upstream vendor.

“Logistics is not merely a primary driver of time and place utilities, but also a core enabler of form and possession utilities” (Fawcett, Waller, & Closs, 2011, p.116).

To explain embeddedness, Granovetter (1985) states that “… the behavior and institutions to be analyzed are so constrained by ongoing social relations that to construe them as independent is a grievous misunderstanding” (p. 482). Extrapolating this comment, researchers visualize supply-chains as configurations comprising sets of organizations (Mena et al., 2013). Each organization is positioned as playing a physical and/or supportive role while contributing to its supply-chain network. Moreover, the visibility and perceptions of reality of each organization depends on its position and role, necessitating understanding the governance and capabilities of these organizations in enhancing performance (Carter et al., 2015).

The principal difference between material transaction and its accompanying logistics activity is that the bundle of goods, services, and resources transferred are unique to their situations. First, the manufacturer buys the material to achieve its target growth and implements logistics while contemplating customer-centric services with its downstream customer. The logistical activities may include MRP, DRP, packaging, transportation, storage, handling returns, and the work-in-process inventory. The change of material possession between the vendor and manufacturer may require activities, such as gathering market intelligence, providing market coverage, and changing the form of a material by the manufacturer.

Second, the accounting practices for the logistics and material buying may be different. For example, the inbound logistics cost are rolled into the purchase price for the manufacturer, but its outbound logistics cost is considered a delivery expense. Third, the reasons for bilateral dependence for material and logistics transactions may be different because of the dissimilarity in the division of labor and activities to achieve economies of scale and scope for adequate performance. For logistics consummation, dependency arises because of service issues (e.g., timely loading and unloading of cargo; inventory count); in the material buying, dependency arises because the purchased material gets integrated into the manufacturer's product. Thus, the manufacturer needs to determine whether this change in the form of the product performs functionally well. Therefore, from a complex adaptiveness perspective, how logistics capability and customer-centric service interact within this material transaction may need to be understood.

Whereas the material sales process may be isolated and understood, the logistics transactions get submerged during the interaction (since multiple logistics tasks are performed using several organizations and government agencies). These tasks may need trucking, warehousing, packaging, homeland security, and infrastructure, and the logistics inefficiencies (e.g., receiving wrong parts and documentation) may easily get diffused. Thus, understanding logistics capability may be necessary.

RBV proponents suggest that organizations conduct business through the bundle of resources they control. The more a resource is valuable, rare, immobile, and non-substitutable, the greater the chances for an organization to obtain a strategic competitive advantage, which has performance-bearing implications. These resources may be classified into physical, human, and organization capital. Physical capital is an organization's control over items, such as technology, plant, location, and raw materials. Examples of human capital are knowledge, training, experience, and skills of the employees. Organization capital encompasses the organization structure and assets for running the organization (Barney, 1991; Dyer & Singh, 1998).

The RBV proponents use capabilities and resources interchangeably (Ray et al., 2004). In this research, the following authors' suggestions are followed. Capabilities are an organization's skills, knowledge, and processes that are used to conduct business in the supply chain (Makadok, 2001). Moreover, these capabilities are entrenched in an organization's routines and practices and act as a glue to integrate and advantageously utilize organizational assets (Day, 1994). These capabilities have causal ambiguities that are complex and situation-specific, and therefore are not only difficult to replicate, but are also time-based that make their transferability difficult to other exchanges (Barney, 1991). Logistics is a capability for order fulfillment filling and service delivery, which includes placing and receiving an order (Day, 1994).

In summary, logistics may be an unnecessary, but required capability to fulfill the needs of the material transfer, and, therefore, it should have its own identity in material buying selling studies. The manufacturer is passing on the levels of relational norms, trust, and commitment built with its upstream supplier to its downstream customer. In this context, the manufacturer needs to coordinate its upstream buying and logistics capabilities with its downstream customer-centric activities to manage the vendor-manufacturer dyad.

Mena et al. (2013) compared three different supply-chain configurations (one set each from the pork, beer, and bread industry) in suppliers' suppliers, suppliers, and buyers' embeddedness. Using a case study and examples, they illustrate that relationship stability (trust, commitment, and communication) and inter dependence grow from less to more as these sets of supply-chains move from an open (one way link to form the chain) to closed (the three organizations linked through a closed loop) system. Since embeddedness was only discussed for the goods exchanged, they suggested to conduct relational embeddedness studies across other sets of supply-chain activities.

Wu, Choi, and Rungtusanatham (2010) surveyed an aerospace-related manufacturer to understand collaborative synergies and market efficiencies of co-opetition (two suppliers of goods simultaneously collaborating and competing). The authors concluded that as supply managers promoted the use of business social interaction, supplier co-opetition (information exchange and joint participation) improved. However, supplier co-opetition negatively affected overall performance, leaving the authors to conclude the need for other forms of embeddedness empirical studies in order to reinforce their study.

Surveying forty-two logisticians, Large, Kramer, and Hartmann (2011) concluded that customer-specific adaptations (behavior and asset specific) improved their client's loyalty and relationship performance; however, adaptations reduced satisfaction although loyalty and relationship performance improved it. The focus of the study, however, was only on logistics service providers rather than the logistics synergies needed in material transaction. The authors recommended conducting additional studies in the purchasing area to demonstrate the importance of logistics and customer-centric service.

Wang et al. (2006) demonstrated the importance of focusing on strategic logistics issues that improve long-term contracts between parties over short-term, cost cutting approaches. “It is interesting to note again that all companies believe improving service quality and customer service are very important for the future, with ranks of 1 and 3” (Wang et al., 2006, p.809).

The recommendations from these embeddedness supply chain studies along with Carter et al.'s (2015) call for launching logistics studies that support physical supply chains corroborate the purpose of this research. An organization's role and position sets its visibility within its supply-chain network. Embeddedness sets an organization's dependence on other organizations in the network; organizations need to rely on each other to managing their capabilities within their configuration.

Thus, it is important that the manufacturer needs to recognize, understand, and admit its perceptions of reality of visibility; a manufacturer and its vendor should realize how each one of them is fulfilling its prophecies without overpushing its agendas. How should they grow material and logistics transactions in this embeddedness while improving performance? Reliance, non-contractual governance, dependence, and their ties with logistics and customer service provide an answer.

Although an organization's supply-chain network establishes the way it participates, reliance through trust and commitment makes the exchange open and fair (Zafeiropoulou & Koufopoulos, 2013). Since superior benefits are highly desired from an exchange, organizations in the supply chain are inclined to commit themselves to maintain the relationships. Gundlach, Achrol, and Mentzer (1995) argue that commitment is an energizing force that motivates organizations to make relatively long-term focused decisions, which strengthen their involvement in future transactions. It defines the closeness of a relationship and the willingness of partners to make short-term sacrifices for long-term, stable relationship (Morgan & Hunt 1994). Manufacturers need both pre and post-sales service over the duration of the warranty period, which are long-term.

Trust is a state rather than something fluid, which is tied with the conditions emanating from trustful over mistrustful forms of governance (Nooteboom, 1996). The presence of trust acts as an informal form of control, which demotivates parties from overanalyzing contracts in inter-organizational transactions (Lui & Ngo, 2004). In addition, trust makes parties keep their business secrets intact, be overly cautious about competitive interference, and thickens their bonds (Katsikeas, Skarmeas, & Bello, 2009). High trust minimizes vulnerability, increases cooperation, and long-term orientation of a relationship (Zhao & Cavusgil, 2006). Trust is defined as a manufacturer's belief that its vendor/shipper is honest, fair, and reliable in its dealings (Bloemer, Pluymaekers, & Odekerken,2013) .

Trust is a condition that directly and indirectly affects an exchange through commitment. “The strength of this belief may lead the firm to make a trusting response or action, whereby the firm commits itself to a possible loss, depending upon the subsequent actions of the other company” (Anderson & Narus 1986, p. 326). Moreover, when trust and commitment partake in the same transaction, they contribute to productive over tension behaviors as well as to the confidence and belief that the parties will not callously destroy an exchange (Lui & Ngo, 2004).

By committing to utilize the material properly while changing its form, the manufacturer trusts that the vendor will release the material in the agreed-upon form. The vendor needs to provide reliable information about the material's properties, availability, future design, or price change. The manufacturer is committed to track the material, worker productivity, safety practices, actual versus documented reasons for delays, type of pilferage, and type of cargo and packaging in close contact with the material.

Hypothesis 1: The greater the vendor's trust, the greater the manufacturer's commitment.

The term governance “is a shorthand expression for the institutional framework in which contracts are initiated, negotiated, adapted, enforced, and monitored” (Palay, 1984, p. 265). Inter-organizational governance may be envisioned as occurring along a hierarchical continuum. The polar ends of this continuum are arms-length transaction and hierarchical governance. Operating within this continuum are different forms of non-contractual governance. Interpreting contracts in inter-organizational relations, Macneil (1980) suggests that the sole purpose of contracts is to implement a set of norms which guide the exchange. From a governance perspective, these norms envelope contracts (Macneil, 1978), simulate hierarchical governance (Grossman & Hart, 1986), and provide governance value for implementing strategies that have competitive advantages (Ghosh & John, 1999).

When the focus is relationships, the reference point for disagreements is not the original contract, but “the entire relation as it had developed to the time of the change in question” (Macneil, 1978, p. 840). Moreover, even though contracts contain written clauses for performing exchanges, certain normative behaviors operate within the relationship to control for the unforeseen not specified in the contracts. Adjustments are made to preserve the longevity of the relationship. Relational norms help the manufacturer manage a non-integrated channel as its own subsidiary. Higher levels of relational norms imply higher levels of governance (Noordewier, John, & Nevin, 1990) .

However, norms have their attached motivation and coordination costs for inter-organizational transactions (Castaldi et al., 2015). Motivation costs refer to imperfect information sharing and commitment between parties. Coordination costs arise from operational difficulties, such as the final delivery (e.g., the last mile), change of possession, and final price (Baudry & Chassagnon, 2012). Unlike corporate governance where the management styles are preserved even if an employee exits (Castaldi et al., 2015), the time and resources for inter-organizational relationship is lost if the exchange is terminated (Palmatier, Dant, & Grewal, 2007; Hartmann & Grahl, 2011).

Timely information sharing or flexibility towards consumer response, continuous replenishment, and delivery are crucial supply-chain practices (Vickery et al., 1999; Bello, Lohtia, & Sangtani, 2004; Fawcett et al., 1997). These norms are communicative, non-evaluative, and promote the shared interest in the exchange that prevent intruders from interfering using genuine or malicious competitive intent (Sachdev & Merz, 2012).

How much should organizations trust each other in order to be comfortable with the visible and invisible portion of the material buying and logistics tasks that occur along its chronological, cost calculus journey? Meaningful communication between organizations is a prerequisite for trust (Anderson & Narus 1990). Moreover, trust is enhanced if interactions between partners are influenced by non-evaluative means (Klimoski & Karol, 1976) .

Manufacturers build a vendor's trust by sharing information and flexible manufacturing to improve forecast accuracy. Vendors and manufacturers may need to plan safety stock at their respective locations to meet uncertainties, which require flexibility and information sharing. One of the reasons for their alliance is that the motivation and coordinating cost to build trust is less than the in-house monitoring cost. Petersen et al. (2008) found manufacturers' supplier integration (buyer's information exchange and degree of strategic partnership) to positively affect relational capital (trust, mutual respect, and interaction).

Hypothesis 2: The higher the relational norms (information sharing and flexibility) between the manufacturer and its vendor, the greater the vendor's trust.

A committed organization espouses its willingness to pursue self-disciplined shared governance and interests (Anderson & Weitz, 1992). A manufacturer primarily commits to change the form and possession of the material by providing the time and place utility functions to complete the logistics movements. The manufacturers' buying and logistics role make them strongly tied to material management at the vendors and manufacturers' site. Based on a sample of U.S. export manufacturers and their distributors, Sachdev and Merz (2012) concluded that manufacturers' relational norms (information sharing and flexibility) increased commitment. Relationship practices enhance mutual understanding and commitment to plan and implement logistics activities (Wong & Karia, 2010).

Hypothesis 3: The higher the relational norms (information sharing and flexibility) between the manufacturer and its vendor, the greater the commitment.

In material transactions, logistics service is a capability since it is crucial, strategic, and reflects the vendor and manufacturer's brand value. Its consistent presence is a primary reminder to the manufacturer of material sales between procurement cycles. By being present up to the last point in a material's journey, a capable logistics service resolves the time and place utilities for a customer and may be viewed as a resource (Sohail et al., 2006; Adams et al., 2014). In addition, it is an enabler for form and possession of the material transfer. It is not easy to mimic logistics processes to create similar brand value. For example, Fawcett et al., (2011) cite companies, such as UPS, Toyota, Wal-Mart, Frito-Lay, Zara, and IKEA to illustrate the power of logistics capability as a sustainable competitive advantage. In particular, they emphasize that it is not tangible resource in itself, but the skill-based (intangible) resource that provides the logistics value. Furthermore, logistics skills are developed through learning-by-doing and cannot be identified, imitated, or transferred across industries (Adams et al., 2014) .

Manufacturers expect flexibility from their vendors to support order releases, emergency orders, after-sales service, and unforeseen supply-chain risks. “A firm's logistical competency is directly related to how well it is able to accommodate such unexpected circumstances” (Bowersox et al. 2013, p. 62). To financially manage its material/logistics convolution, the manufacturer rolls its logistics cost into its material cost to make it part of its asset management. Purchasing cost may need to be adjusted to improve each other's balance sheet and /or income statement, which brings information sharing and flexibility in the forefront. Flexibility may be regarded as a potential driver of competitive advantage for a logistics strategy (Fawcett et al., 1997).

Hypothesis 4: Greater relational norms (information sharing and flexibility) between the manufacturer and its vendor lead to greater logistics capability.

Customers do not buy products and services, but the utilities derived from them. The service-dominant logic (SD-L) literature also suggests that organizations should collaboratively identify and cultivate value-added activities, gauge market feedback, and evaluate performance (Lusch, Vargo, & Malter, 2006). Therefore, customer-centric service needs to be incorporated as part of the value-creation activity in any line of business. Moreover, customer-centric service affects the brand image of the organization and/or its product.

Logistics service tied with customer service reflects how well an organization utilizes logistics activities in retaining its customer (Oflaç, Sullivan, & Baltacioğlu, 2012). Studying one without the other may not capture the overall serviceability of the organization. In addition, in order to understand the spill-over effect, customer service is important to manufacturers. Furthermore, if logistics is not partitioned from material transaction, “…failure situation can create considerable shifts in the responses of consumers, especially in the attribution behavior for cause of failure” Oflac et al. (2012, p. 51). Therefore, the authors treat logistics service capability and customer-centric as two related, but separate issues.

Collaborative efforts in relationship development enhances the chances of differentiating one’s services (Adams, et al., 2014). However, more research is needed to determine which types of relationship improve customer-centric service relative to competitors in different relationship context (Daugherty, 2011). For supply-chains, continuous acquisition and integration of information is needed to be customer-centric (Homburg, Wieseke, & Hoyer, 2009; Kumar, Heide, & Wathne, 2011).

Manufacturers develop relational norms after taking the sales and after sales services requirements into consideration. The more the manufacturer can socially identify with its upstream vendor, the higher the probability of transferring this social identity to its downstream customers (Homburg et al., 2009).

Hypothesis 5: The greater the relational norms (information sharing and flexibility) between the manufacturer and its vendor, the greater the manufacturer's customer-centric behavior.

The manufacturer contracts and co-creates material value with its vendor to enhancing its downstream customer-centric experience. This customer-centric experience is transferred through the manufacturer to the downstream customer (Kumar et al., 2011). Hence, the manufacturer needs to commit to its material transactions with the vendor before it can provide the customer-centric experience. A customer-centric organization focuses on collecting customer feedback and resolving conflict while playing a strong commitment role (Bradford & Weitz, 2009). An optimistic post-sales customer service may be positively affected by commitment (Challagalla, Venkatesh, & Kohli, 2009) .

Hypothesis 6: The greater the manufacturer's commitment towards its vendor, the greater its customer-centric service.

Dependence sows the seed for distribution and logistics management (Sachdev et al., 1995). “The dependence of actor P upon actor O is (1) directly proportional to P's motivational investment in goals mediated by O, and (2) inversely proportional to the availability of those goals to P out-side of the O-P relation” (Emerson, 1962, p. 32-33). This dependence definition focuses on two factors: commitment and alternatives available to the parties being influenced (Beier & Stern, 1969). Dependence is tied with goal accomplishment, replaceability issues, and longevity of the relationships to recover the motivational investment and not a principal driver of trust between parties (Katsikeas et al., 2009).

A manufacturer becomes dependent on his vendor to complete the buying process. The dependence to commitment path arises because the vendor needs to accept the purchase order and may provide financial incentives. The vendor's dependence lies on how well the manufacturer transforms the purchased material before shipping it to the next set of customers.

When bilateral dependence between organizations is low, there may be little reason to build commitment. The interests of such parties are divergent and the motivation to conduct business is pure arms-length. The manufacturer may shop around for emergency orders to meet its short-term goals of storing and moving inventory and may delay or cut back on vendor material purchase. In the case of high bilateral dependence, each party has an economic stake in the outcome, and convergence of self-interest to pursue opportunities prevails. In addition, if partners value the benefits from each other's resources, they are less likely to replace each other and instead be motivated to increase the on-going partnership. Commitment will replace reasons for generating vulnerability. High levels of bilateral dependence between partners result in less likelihood for negative sentiments (Kumar et al., 1995). It also encourages the formation of normative compliance and extendedness to a relationship (Lusch & Brown, 1996).

Hypothesis 7: The higher the bilateral dependence between the manufacturer and its vendor, the higher the manufacturer's commitment.

Through performance one distinguishes successful from unsuccessful B-S relationships. Moreover, positive outcomes ensure that valuable resources flow appropriately through one's supply chain for extended periods (Chen, Daugherty, & Landry, 2009). Performance should be measured from both the buyer and seller's side (Kumar, Stern, & Achrol, 1992). In addition, performance may be measured through hard, contribution to profit measures or soft, perceptual measures such as the degree of success with a partner. Hard measures of performance are more closely linked with the product and the attached services sold than soft measures (Large, et al., 2011). The manufacturer is interested in improving its financial statements through appropriate B2B pricing strategies, adjusted for logistics cost.

Although resources and capabilities strengthen an organization's competitive advantage, they become a relational rent for the giver (Dyer & Singh, 1998) . The manufacturer aligns its order processing and inventory to match its DRP with its MRP. Efficient logistical interactions and activities reduce costs and enable the participating organizations to better utilize their assets and improve performance (Lynch, Keller, & Ozment, 2000) .

Hypothesis 8: As a manufacturer's logistics service capability improves, its financial performance improves.

How well an organization attracts new customers or retains existing ones is determined by its service-quality (Oflaç et al., 2012). “Value is not produced in the supplier's factory, but in the buyer's use of the goods, services, information, and other inputs the seller provides. Customer relationship marketing involves getting close to customers, understanding their agendas, determining how to profitably facilitate those agendas, then working collaboratively with customers to accomplish their goals” (Fung, Chen, & Yup, 2007, p.167).

The manufacturer needs to coagulate its downstream customer experience as well as its own, learn from it, and share the knowledge with its vendor. It is through gauging market feedback that one improves performance (Vargo & Lusch, 2004).

Hypothesis 9: As a manufacturer's customer-centric service improves, perceived performance with its vendor improves.

It is through commitment, exchange partners simulate the benefits, avoid the bureaucratic inefficiencies, and realize the economies of scale of vertical integration (Gilliland & Bello, 2002). Bloemer et al. (2013) state that commitment motivates an entire organization to develop the skills and competencies, which are necessary for its success.

If a manufacturer foresees a committed relationship with its vendor, it may hedge its business activities over a longer duration. The manufacturer may better contemplate its spill-over effect through the continued availability of its vendor's brand, and plan strategies and generate potential sales without the fear of losing future business.

A committed relationship may integrate each organization's expertise in creating and delivering value and enhancing supply-chain performance. Organizations are less fearful of being exploited and are more willing to share their capabilities and resources (Wallenburg et al., 2011). Moreover, committed buyers and sellers may readily access market information needed for creating and delivering value. It also encourages a partner to allocate more time to the relationship and increases performance (Anderson & Weitz, 1992). In addition, commitment signals by one party motivates the other to efficiently engage in the role requirements for the exchange (Kim & Frazier, 1997). Commitment increases the chances of a party to be less short-run focused, knowing that the overall performance balances in the end (Bello, Chelariu, & Zhang 2003).

Hypothesis 10: As a manufacturer's commitment improves, its perceived performance with its vendor improves.

A survey was distributed via email to pre-identified manufacturers using the services of a market research firm (an Internet-based provider that had access to a panel comprising a variety of U.S. manufacturers). To qualify for the final sample, the key informant needed to be a decision-maker for a manufacturer purchasing processed materials and or/component parts from vendors. Based on the resources set aside for data collection, a list of 200 randomly selected purchasing managers, who worked for a manufacturer, were contacted by the marketing research firm. The first 150 manufacturers who respond to this survey were included in the sample. Considering the time, effort, and complexity in gathering data from supply-chain professionals, several research studies have used the assistance of a data collecting agency with the involvement of the principal researcher (e.g., Zacharia, Nix, & Lusch, 2009).

All questionnaire items were borrowed from supply-chain literature: Commitment from Palmatier et al. (2007); information sharing from Zhao, Dröge, and Stank (2001); flexibility from Noordewier et al., (1990); logistics service and financial performance from Lynch et al. (2000); customer-centric service from Khong (2005); dependence and perceptual performance from Jap and Ganesan (2000); and trust from Judge and Dooley (2006). Wordings were adjusted to ensure that the manufacturer was focusing on its primary vendor. Each questionnaire item was measured on a 7 point Likert agree/disagree scale.

In supply-chain literature, dependence has been measured as the sum or difference between each partner's dependence. However, Peter, Churchill, Jr., and Brown (1993) exhibit caution when a single respondent provides his/her perception on attitudinal items pertaining to both sides of a dyad and the difference computed as the final measure. They instead offer two suggestions: use direct comparison (e.g. agree/disagree scale – the organizations are highly dependent on each other), or frame the question as a difference in perception. In this study, the authors have offered a third suggestion: bilateral dependence is a second-order construct consisting of the perceptions of each side's dependence from a single respondent. In addition, since information sharing and flexibility are general forms of collaboration for purchase and logistics (Bowersox et al., 2013), the authors integrate them into a second order construct (Sachdev and Merz, 2012).

To test the hypotheses, Structural Equation Model (SEM) using the partial least squares (LV-PLS) algorithm (Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005) and Smart PLS was used. A path weighting scheme with initial weights of 1.0, 300 iteration maximum, and an abort criterion of 1.0E-5 were used to estimate the model reported here (Hair et al. 2012) . In addition, t-statistics for all the paths, weights, and loadings were generated by a bootstrapping routine using 5000 re-samples of the cases available for modeling (Hair et al., 2012).

The path model that consisted of ten first-order latent variables with a total of 48 items (reflective) were subject to an exploratory factor and reliability analysis. Evaluation criteria of Eigenvalue greater than one, minimal cross-loadings, and reliability (coefficient alpha) greater than 0.7 were used (Hair et al., 2010). Of the four perceptual performance items, two were dropped as they were not contributing to the success of supply chains. The 10 customer-centric items were loaded on three separate factors. Two factors, comprised marketing research and information gathering/analysis, respectively; consequently, they were dropped. Four items related to the delivery and management of customer-centric service were retained. The resulting four-item, customer-centric and two-item performance scales had coefficient alphas of greater than 0.7 for the sample (Nunnally, 1978).

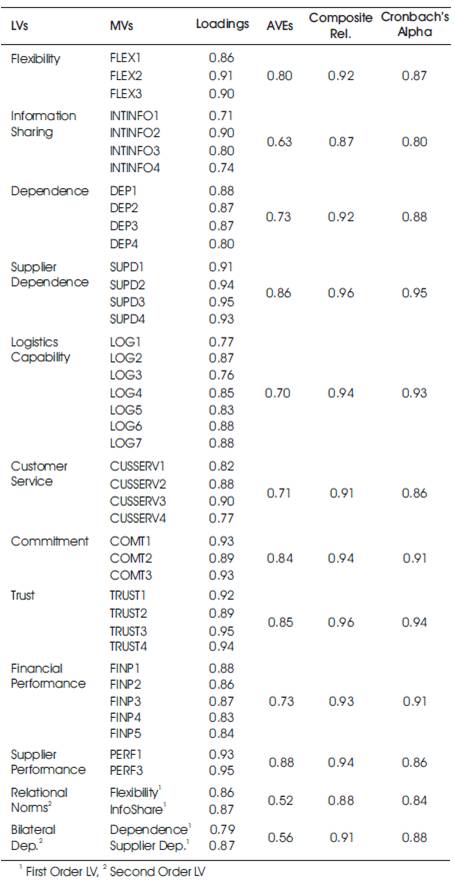

Table 1 displays the measurement model (LV-latent variables; MV-manifest variables; item loadings, average variance explained, composite and Cronbach alpha reliability). Based on Fornell and Larker (1981) guidelines, manifest items meet greater than 0.7 loading criteria. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeded the 0.5 criteria except the composite reliabilities and alpha coefficients which exceeded their suggested greater than 0.7 criteria.

Table 1. Measurement Model Summary

In addition, for convergent validity, the manifest measures should load greater than 0.6 on their single latent construct and exhibit minimal cross-loadings. An examination of the cross-loadings did not reveal any severe levels of cross correlations among the predictor constructs, so, overall, the construct validity of the models is satisfactory. Furthermore, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) measures the variance captured by the indicators relative to the measurement error and should be greater than 0.5 to justify using a construct (Barclay, Thompson, & Higgins, 1995).

Discriminate validity is assessed by comparing the square root of the AVEs for the latent variables against the correlations of the other latent variables in the model. The self-explained Table 2 shows the results of this assessment. The AVEs are larger than the off diagonal correlations with the other latent variables in the model, demonstrating acceptable discriminant validity.

The structural model was assessed by examining the coefficients of determination (R2) as indicators of overall predictive strength along with the significance levels of the coefficients for the hypothesized paths. The coefficients of determination (R2) (see Table 2) show that the model explains a substantial part of the variance in logistics capability (0.351), customer service (0.352), commitment (0.612), trust (0.234), and vendor/client performance (0.517). Financial performance is only weakly explained with an R2 of 0.095.

The significance of the path coefficients was evaluated by t-statistics generated from a bootstrapping routine that produced sample parameter estimates and its standard errors (S.E.- Initial estimates - I). The results of this procedure including the Initial path coefficients (I), bootstrap path coefficient standard errors (S.E. of initial path - I), t-statistics (using the initial S.E.), and p values are displayed in Table 3. All hypotheses are supported (see Table 3).

Most organizations in the supply chain focus their efforts on pricing their respective transactions, reasons for service failure, and complaints of the parties involved rather than understanding the relational embeddedness and ways of improving it (Halldo´ rsson & Skjøtt- Larsen, 2006). Since embeddedness may vary according to the nature of the transaction, an organization needs to analyze its transacting embeddedness to better manage its exchange (Choi & Kim 2008). The authors explore material and logistics embeddedness from manufacturers' perspective. These manufacturers purchased processed materials or components from their vendors. Information sharing, flexibility, dependence, trust, commitment, logistics service, customer-centric service reflected embeddedness. All the 10 hypothesized paths were supported.

The proven hypotheses indicate that it is important to study the type and degree of embeddedness. A manufacturer and his vendor have a choice between short-term buying and long-term relationship. If the overall goal of these organizations is disintermediation, a participant may gradually assume more supply-chain activities over its trading partners as its business grows. “The supply chain as a network operates as a complex adaptive system, where every agent grapples with the tension between control and emergence” (Carter et al., 2015, p. 91). For instance, Mena et al. (2013) traced food industries to exemplify open, transition, and closed systems as a means of an organization to garnish control within one's immediate set of supply chains.

However, several researchers argue that inter-organizational transactions may benefit from relationship techniques to sustain an open over a closed system through continuous learning to resolve tension and overly controlling issues (e.g., Macneil, 1980; Noordewier et al., 1990). Our results attest that by using the relational embeddedness to one's advantage, supply chains may co-exist as open systems. Organizations may learn to be dependent and use non-contractual forms of governance that fits with one's structural embeddedness (role and position). In the case of material and logistics embeddedness in a vendor-manufacturer interaction, information sharing, flexibility, trust and commitment may generate the same effect as of a closed system.

Bilateral dependence, construed as second-order, directly affected commitment. As discussed, dependence may set the stage for collaboration. Sachdev and Merz (2012) found manufacturers' dependence to increase commitment with export distributors although trust was not a part of the model. Zacharia et al. (2009) found manufacturers and their collaborative partners' interdependence to positively affect collaboration (information sharing and joint effort); collaboration, in turn, affected relational outcome (trust, commitment, credibility, and relationship effectiveness). Utilizing a sample of import distributors, Katiskeas et al. (2009) found overseas manufacturer-importer interdependence to moderate the effect of trust on performance.

Therefore, the reasons and degree of each organization's dependence should be delineated before resources are developed and deployed in an exchange. These reasons help to understand the interplay between dependence and other constructs within a framework. Dependence may affect exchanges based on how it is measured and the type of embeddedness (role, position, and relationship degree between the exchange parties).

Since relational norms may not be equally applicable to every buyer-seller exchange, the results indicate that an organization should select the norms that will be helpful in deploying capabilities according to the organization's position and role. Relational norm (information sharing and flexibility) affected trust and commitment. Manufacturers and vendors should empower their employees to jointly utilize flexibility and information sharing to improve trust and commitment. Myriad logistics sub-tasks may need to be performed in order to fulfill each material transaction. On occasions, more visionary thinking may be needed. Flexibility and its corresponding information sharing (second-order) reminds the manufacturer-vendor of the trustworthiness and commitment in this line of business.

Morgan and Hunt (1994) found communication (information sharing and exchange expectations) to affect tire dealers' trust with their vendors; however, communication's path to commitment was not hypothesized in their study. Using sample buyers from different manufacturing industries, Zacharia et al. (2009) found higher degrees of collaboration (information sharing and joint effort) between manufacturers and their collaborative partners (sellers) to result in higher relational outcome (an additive scale comprising trust, commitment, credibility, and relationship effectiveness items). The authors illustrate that information sharing and flexibility jointly affect commitment and corroborate the reason for contextual-based embeddedness research. Organizations need to recognize their role in their respective supply-chains, and establish policies for their employees to provide the proper category and combination of relational norms.

“A positive influence of trust on commitment is at the core of the commitment-trust theory” Wallenburg et al., 2011, p. 85). Although trust-commitment are important parameters and essential for long-term relationships, few researchers incorporate both constructs in a study and directly interrelate them (e.g. Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Wallenburg et al., 2011). Moreover, hardly any study measures commitment's impact on performance in the presence of trust. For instance, Katsikeas et al. (2009) found trust to strengthen the density and thickness of overseas' manufacturer-importers. Skarmeas, Katsikeas, and Schlegelmilch (2002) found commitment to be positively related to performance in their manufacturer overseas' distributor study. Lages, Lancastre, and Lages (2008) demonstrated relationship performance to be a higher-order concept comprising commitment, trust, mutual cooperation, and satisfaction for B2B emarketplace transactions.

Flexibility and information sharing, in unison, positively affected logistics services capability. However, in their B2B study, Palmatier et al. (2007) found manufacturers and distributor capabilities to be affected by different sets of governance parameters: Distributors' relationship specific investment (e.g., knowledge and special procedures) was affected by communication, but manufacturers' relationship-specific investment (e.g., training and customized support) was affected by both communication (timely and accurate) and relational norms (flexibility, solidarity, and mutuality).

Service provided as a result of logistics operations is often considered an appropriate yard stick for competitive advantage and an intermediate outcome to performance (Adams et al., 2014). Because not all resources or capabilities have a sustainable competitive advantage and some may be neutral or negatively affect performance, this study extends RBV by illustrating why each type of buyer-seller embeddedness may need different type of capabilities for its sustenance. In addition, different non-contractual governance may be needed to guide the different capabilities.

Generally, vendors and manufacturers encounter dynamic conditions that need accommodative strategies. Being flexible and disclosing detailed proprietary and non-proprietary information guide logistics service capability. Although manufacturers' logistics service capability was positively affected by relational norms, they may need to pay close attention to their tactical logistics ser vice (MRP, inner-plant transportation systems, etc.) to reap the benefits of time, place, form, and possession utilities.

Service Dominant-Logic (SD-L) proponents proclaim that buyers are more interested in the benefits from an exchange than the physical assets that contribute to it. In addition, the co-created value is derived from customer's perception of these values and the organization's application of its resources in delivering the value (Vargo & Lusch, 2004; Adams et al., 2014). The findings of this study attest that irrespective of the type of transaction, the SD-L approach holds true. From the material buyers' (manufacturers) perspective, relational norms (information sharing and flexibility), positively affected customer-centric services. Hartmann and Grahl, (2011) research findings reveal that, from logistics buyers' perspective, flexibility positively related customer loyalty across German-based industries.

Since performance has been related to several traits in business literature, researchers generally select the closet trait within a framework that affects it. As discussed earlier, financial performance closely relates with the material and logistics tied with it, and perceptual, global measures more closely relate with the customer services received as a result of the material sales transaction. Based on these performance-related ideologies, manufacturers increased their financial performance that emanated from their logistics capabilities. Being customer-centric also enhanced their perceptive-performance assessment of vendors. Commitment had its individual impact on perceived performance as hypothesized.

Hardly any B2B empirical study has examined commitment's effect on performance. For instance, Skarmeas et al. (2002) found importer commitment to improve performance with its overseas manufacturers. A few researchers prefer splitting commitment into attitudinal categories (affective and calculative) to show each category's direct and indirect effect on perceptual performance. Bloemer et al. (2013) found calculative commitment to affect export performance for general Netherlands exporters. However, these studies do not include both trust and commitment as part of the model. The authors found trust to have a direct impact on commitment and the global measure of commitment to directly affect perceived performance.

If supply chains are envisioned as configurations of their larger supply network, then, the organization that initiates its configuration (e.g. a manufacturer with its upstream vendor and spill-over effect with its downstream customer) is accountable to rest of its supply network for the continued existence of its configuration. An organization's financial performance relative to its competitor is one way of demonstrating the popularity of its configuration. Perceptual performance is also one of the ways of guaranteeing that an organization in the configuration will not lose its position (Mena et al., 2013). Through positive perceptual performance, the authors of this study illustrated why and how the vendor will not by-pass the manufacturer or vice-versa (disintermediation).

This study is not without its limitations. First, the data was gathered using the service of an Internet-based marketing research organization, who had a preselected set of purchasing managers in their database. Second, a key informant was identified in each case and selfreported measures were gathered of the questionnaire items. Hence, self-reported bias may not be ruled out since some questionnaire items captured the selfinformant's perceptions of his/her own organization, whereas others captured his/her perceptions about the vendor's attributes. Nevertheless, this exploratory study does contribute to a gap in literature that supply-chain organization's role and position and transaction embeddedness should be taken into consideration before allocating resources.

Although tangible resources were not discussed in this study, their impact should not be ignored. Future research should identify tangible resources and study them in conjunction with the intangible capabilities. For example, tangible information technological resources may interact with intangible human resource (skills of using technology) to explain performance. It is common knowledge that different employees using the same machine tools and materials may create different degrees of quality. In addition, this study focused on a material buyer's perspective with respect to its exchange (manufacturer-vendor) and a downstream customer with whom it would presumably conduct business. This study did not gather any information about this downstream customer. Future studies may benefit by gathering information from the three supply-chain organizations.

Lastly, in this research, supply chain was defined as any manufacturer (OEM (Original Equipment Manufacture), component part, processed material) purchasing material from any type of supplier/vendor (OEM, raw material, component part). Future research may benefit from measuring compatible sets of supply chain. For example, a compatible chain may be processed from material manufacturers purchasing raw materials from a mining industry.

The purpose of this study was to elaborate how embedded organizations should strive for continuity by simulating a hierarchical structure of governance. The authors explored embeddedness efficiency resulting from the material and logistics transactions in a manufacturer and vendor dyad. The social adaptive tools of relational norms (information sharing and flexibility), trust, commitment, and dependence were hypothesized to explain the manufacturers' logistics capability and customer-centric services that are embedded in material buying between a vendor and a manufacturer. Practicing such behaviors may prevent supply-chain failures such as those experienced by Mattel Toys, Inc.