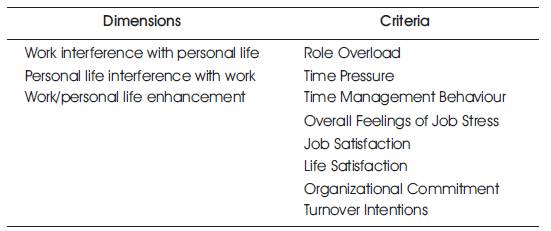

Table 1. The Three Main Dimensions of Work-life Balance and Criteria to Measure them. Source: (Fisher, 2001 p. 35)

Work-life balance continues to be one of the most important issues for employees from all avenues of work and from the majority of countries in the world. The topic has always been of fundamental interest to employees and employers. In this era of an increasingly digital workplace, it continues to be a source of rich and ongoing discussions. Canada has always stood among the leaders of the industrialized world in advocating for a healthy quality of Work-Life Balance (WLB). It is virtually paradoxical that Canada is still at the discussion stage with regard to settling this issue. One would think that the country would have determined the parameters of the concept by this time. There is still much to be learned. It is in this context that the model in Denmark becomes crucially germane. The WLB question seems to have been dealt within that country. It is left to be seen and understood how Canada's outlook compares to that of a world leader such as Denmark. This paper deals with the effect that the implementation of the Denmark workplace model might have in Canada vis-àvis work-life balance. The research revealed that there are differences in perceptions of work and flexibility between Canadians and Danes. Given the data analysis, the Danish Workplace Model may not suit Canada.

Work-life balance is defined as an individual's ability to meet both their work and family commitments, as well as other non-work responsibilities and activities (Parkes and Langford, 2008) . The workplace environment in the United-States and Canada is represented by a business model that focuses on increasing profitability and enhancing efficiency, in which, employees tend to work hard and productively (Gao, 2015). In the recent years, Work-Life Balance (WLB) has been the subject of many discussions in Canada, where criteria such as conflict and time management were discussed as being major variables that affect the work-life balance of Canadian employees. In 2014, Kjerulf reported that there were many Americans who do not enjoy their jobs, while Danish people were happier than American workers(Kjerulf, 2014) due to reasons such as working hours, as well as work and life balance. A pertinent question here is whether the Canadian employee experiences the kind of work-life balance that causes him to be satisfied and consequently contributes the best effort in favour of the organization for which he works?

The motivation for this research originated from the OECD report released in 2014 in which Denmark ranked highest in work-life balance and life satisfaction indices, in factors where Canada lagged behind(OECD, 2014a) (See Appendix A). The report addresses an analysis of the factors affecting work-life balance, its impact on the Denmark and whether its application to Canada would have a positive outcome on the country.

Michael Harrison in his book “Diagnosing Organisations” substituted the term ‘Work-life-balance’ with the term ‘Quality-of-Work-Life (QWL)’ and referred to it in terms of the degree to which work in an organization contributes to material and psychological wellbeing of its members (Harrison, 2005). Other researchers defined the work-lifebalance as the result of a process in the organisation in which managers and leaders involve employees collaboratively in their decision-making (Empyreal Institute of Higher Education, 2015). The term quality of work-life appeared first in the industrial revolution era when legislation was created to protect employees against job injuries (International Science Congress Association ISCA, 2014). However, researchers found it difficult to define the term 'quality-of-work-life' until the early 1970's, when the term was defined as the process by which organizations' management teams enable employees to define and shape organizations' cultures, decisions and futures (Kaila, 2006, p. 429). The term was later expanded to include the extent to which employees are able to satisfy their desires within the organization (Empyreal Institute of Higher Education, 2015, p. 25). They also separated between the sphere of work and the sphere of personal life (pp. 240- 251). A similar approach was used by O'Driscoll who separated job roles and off-job roles, and indicated that the interaction between both types of roles can lead either to enhancements or conflicts(O'Driscoll, 1996, p. 279-306) . Cooper and Rousseau (2000) defined work-life balance as a balanced position that an individual achieves in all aspects of his life. Clark however defined work-life balance as a satisfying personal state with minimum or no conflict between roles at home and roles at work(Clark, 2001, p. 348-365). Sawhney and Khatri summarized employees' expectations with the seven major aspects of good compensation, safety, security of job, autonomy, integration in the organization culture, good social environment, and a potential career path (Empyreal Institute of Higher Education, 2015). Morris and Madsen (2007) concluded that when employees' resources such as allocated personal time, personal financial resources, mindset focus, self-energy, are applied in the work domain, they translate to a decrease of their availability at the personal domain level (Morris & Madsen, 2007, p. 439-454). As a result, the work-life balance could be evaluated by assessing the level of investment of personal resources in the work domain compared to their availability in the employee's non-work domain.

Marshall and Barnett researched the work-family strains and gains among 300 couples and concluded that a spill of stress from work was a major factor that affects workfamily balance gains and increase work-family strains (Marshall & Barnett, 1993, p. 64-78). Sue Campbell Clark identified work-life balance as a satisfying personal state with minimum or no conflict between the roles at home and at work (Clark, 2001, p. 348-365). She concluded that work-life balance depends on the level of engagement of the employees at work to create the environment in which they disposition themselves to get the necessary support and flexibility they need (p. 353).

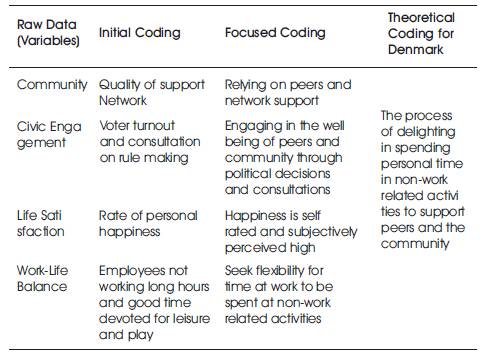

Fisher looked at the dimensions of work-life balance and the criteria to measure them (Fisher, 2001) as shown in Table 1. Fisher stressed that all these factors are evidence that they should be used to assess work-life balance since they give a broader means to assess the subject from different angles. The dimensions used were instructive and provided insight into understanding work-life balance.

Table 1. The Three Main Dimensions of Work-life Balance and Criteria to Measure them. Source: (Fisher, 2001 p. 35)

Another study assessed work-life balance based on four factors: (1) Factor of family conflict which affects work, (2) Factor of work conflict which affects family, (3) Factor of family to work enhancement, and (4) Factor of work to family enhancement(Grzywacz & Carlson, 2007, p. 455- 471). They concluded that work-life balance results from low levels of the first two factors, i.e. both types of conflicts, and high levels of the last two factors, i.e. both types of enhancements.

Tausing and Fenwick (2001) concluded that measuring the level of schedule control among individuals is a better indicator of perceived work-life balance than the availability of schedule alternatives (p. 101-119). However, most of the researchers seem to concur that the measurements of the work-life balance of an employee should assess the level of conflict and stress spilling from work roles to personal roles and vice versa, time allocation and time management, the perceptions about personal control and the ability to balance work and life, and to prepare in the organisation for such flexibility(Zedeck & Mosier, 1990).

Many factors could affect employees' work-life balance and they vary depending on the employees' gender, generation, type of work, seniority and location. Maharshi and Chaturvedi determined four factors: (1) Personal commitment, (2) Job productivity & performance, (3) Work task, and (4) Time management (Maharshi & Chaturvedi, 2015, p. 132).

The University of Georgia determined nine factors to affect work-life balance: (1) Participation, (2) Work-family interference, (3) Management-employee relations, (4) Organizational effectiveness, (5) Safety climate, (6) Job content, (7) Advancement potential, (8) Resource adequacy, and (9) Supervisor support (University of Georgia, 2012, p. 423).

Shobitha Poulose grouped the factors affecting employees' work-life balance into three categories: (1) Individual factors, (2) Organizational factors, and (3) Social factors(Poulose, 2014, p. 5). The individual category included the employee's personality, the employee's well-being, as well as the employee's emotional intelligence (pp. 5-6). She listed in the second category the good work arrangements, the work policies built towards good work-life balance, the management's support and flexibility, as well as the low work stress, and the availability of good work technologies (pp. 6-8). Some of the social factors affecting work-life balance are family influences and support, children responsibilities, spouse support and employment and family conflict (pp. 6-8).

The goal of the paper was to answer the following research question:

Would the application and implementation of the Danish Workplace Model have a positive outcome in the North American context and specifically, in Canada?

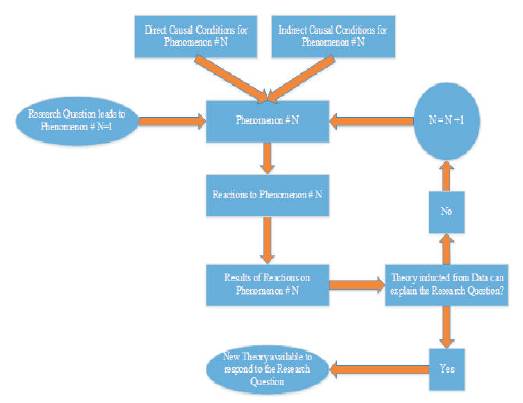

The method of analysis used in this paper was the Grounded Theory (GT) approach with axial coding(Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Grounded theory with axial coding consists of identifying categories and/or properties, then linking these categories and/or properties to each other by inductive and deductive thinking through causal relationships identification (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). The relationship between these five elements is illustrated in Figure 1. The phenomenon triggers certain reactions, which lead to certain results. These new results create the conditions for a new phenomenon and the process chain is triggered again until a theory obtained from the data can explain the research question.

Figure 1. Relationship between the Grounded Theory Five Axial Coding Elements and the Recurrence of the Process. Source: Authors, based on Borgatti, 1996

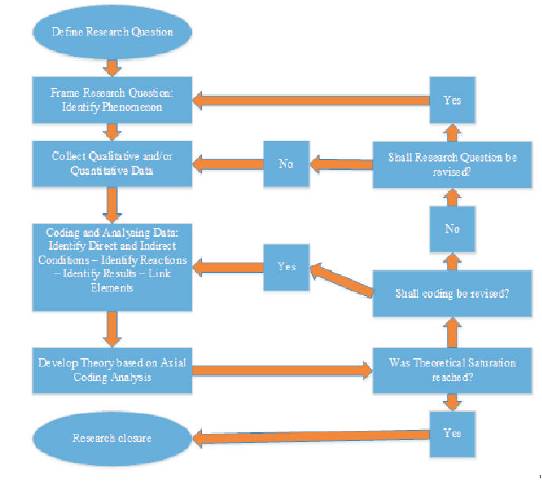

The process followed in this research is illustrated in Figure 2, and it details the steps and conditions to start and close the research. A sequence of iterations were followed until a satisfying theory is reached.

Figure 2. Grounded Theory Research Process Iteration. Source: Authors, based on Bitsch, 2005, p. 78

The research focused first on identifying the theory behind the work-life balance in Denmark. The theory underlying the concepts of establishing a work-life balance in Canada from a Canadian perspective was then examined. The two analyzed theories were then compared for matching elements. A full match would translate to a positive outcome when implementing the, Danish Workplace Model of work-life balance in Canada.

Work-Life balance measured by the OECD consisted of two variables. The first measured the number of employees working an average of 50 hours or more a week, while the second measured the average time devoted for leisure and personal care(OECD, 2014b). The scores of all the variables surveyed by the OECD are listed in Table 2 in which the highest scores between both countries are shown here underlined. Tables 3 and 4 below detailed the codes for the top scores for Denmark and Canada, with the respective theories behind the codes.

Relationships between the variables in Table 3 could be described as the process of delighting in spending personal time in non-work related activities to support peers and the community.

Table 3. Coding Process for Denmark Top Rating Variables over Canada. Source: Authors, based on information from (OECD, 2014a)

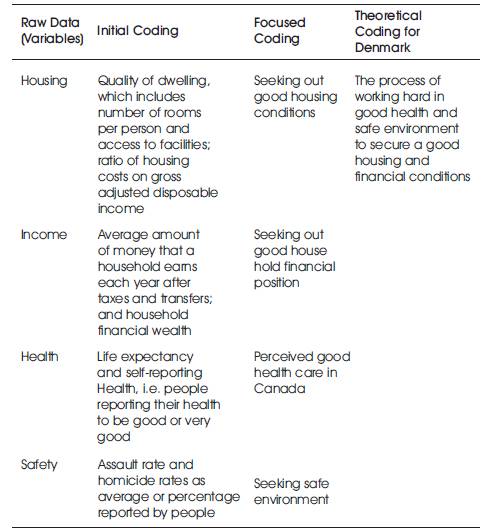

The relationships between the variables in Table 4 could be described as the process of working hard in good health and safe environment to secure good housing and financial conditions.

Table 4. Coding Process for Canada Top Rating Variables over Denmark. Source: Authors based on information from (OECD, 2014b)

As a result, both countries were not on the same page when it comes to the top ranking variables in the OECD report. Hence the importance of axial coding that will be used next as a tool to analyze the reasons (the “why”) and the mechanisms (the “how”) of the implementation of the changes that lead to a good work-life balance in Denmark.

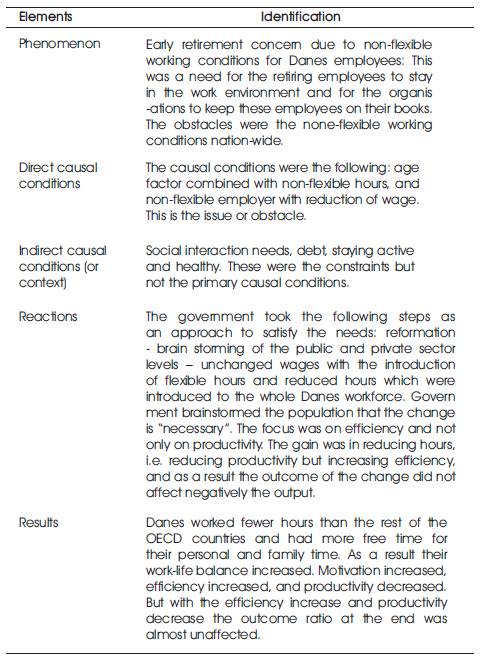

In 2001, in the Nordic Labour Journal, Berit Kvam wrote the following on the theme of flexible working conditions in Denmark:

“It is better to change the workplace than to force people into early retirement. This is the catch phrase of a reform currently taking place in Denmark. New ways of working have been introduced: flexible working arrangements and sheltered employment” (Kvam, 2001)

Flexible working conditions were first introduced in 1994, then updated in 1996 and continued in the early 2000s. The elements of axial coding are listed in Table 5.

Table 5. Axial Coding Elements of the Introduction of Reduced Hours and Flexible Hours in Denmark between 1998 and 2001. Source: Authors based on Kvam, 2001

In summary, four steps were deducted as the base of the theory behind how the implementation of work-life balance took place in Denmark:

(1) A nation-wide need identified first by employee.

(2) Obstacles to satisfy the need were identified by employees.

(3) Organizations were ready with open mind to intervene and apply changes to satisfy employees needs.

(4) Change identified as a necessity through nation-wide intervention and brainstorming.

It is important to mention that the research analysed and confirmed that there were no significant negative effects of the introduction of flexible working conditions because the solution was based on an existing need from the perspectives of both the employee and organizations. Amenable work-life balance led to increased motivation at the workplace (Appendix B).

The four steps extracted from the analysis of Table 5 can also be described as two parallel sequences happening at the same time. The sequence (A) consisted of steps (1), (2) and (3) while the sequence (B) consisted of step (4). If (B) alone happens, the result will be that the employees will take advantage and will not feel any expectation was met due to the absence of need. If (A) alone happens, then organizations will not feel that they are driving the reform and in control, but will rather feel pressure from the employees to accommodate them and as a result may not be buying in the idea of change as a necessity. Hence the theory is as follows:

(A) Consisted of steps (1), (2) and (3).

(B) Consisted of Step (4).

Where both sequences had to coexist and be triggered in parallel (A)// (B).

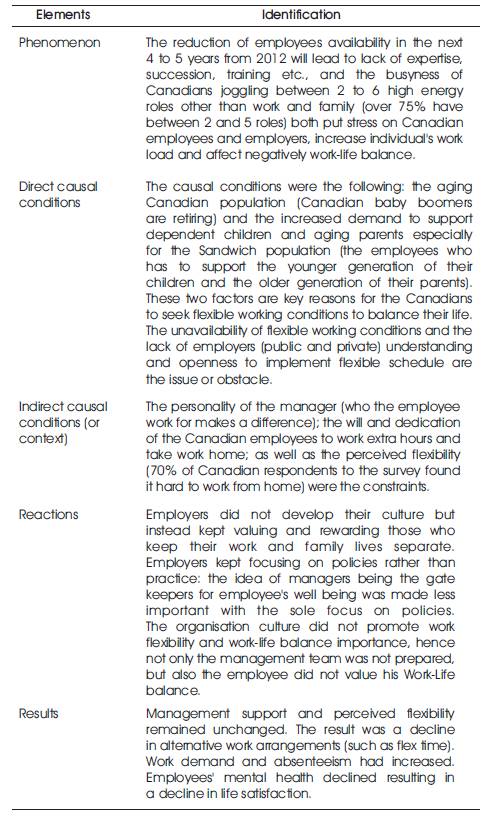

Research done at Carlton University in 2012 revisited the work-life issues in Canadian work environment in comparison with two reports done in 2001 and 1991, and claimed that many Canadians will retire in 4 to 5 years and organisations will have issues in training, succession, etc. (Duxbury & Higgins, 2013, pp. 29 & 49). As a result, these circumstances seem similar to the ones of Denmark in the mid 1990s. However, the report stated that despite these circumstances and the aging of the Canadian population, the use of flex time has surprisingly declined over time, and the perceived flexibility of management support remained relatively unchanged from 1991 and 2001 report(Duxbury & Higgins, 2013, p. 119). An axial coding analyzed the conditions behind these findings in Table 6.

Table 6. Axial Coding Elements of the Reaction of Employers towards the need of employees' flexible hours to balance their work-life activities. Source: Authors based on Duxbury & Higgins, (2013)

As a summary for this analysis, it can be deducted that there is a nation-wide need identified by employees and employers, the employees know the obstacles, but the organisations were not ready to implement flexitime or change their culture. As a result, employees put more hours at work and even take their work home. The following can be deducted in comparison with the theory established previously in the Denmark's analysis:

(1) A nation-wide need was identified first by employees.

(2) Obstacles to satisfy the need were identified by employees.

(3) Organizations were NOT ready with open mind to intervene and apply changes to their culture in order to satisfy employees' needs.

(4) Change was NOT identified as a necessity through nation-wide intervention.

It can be deducted that the first two points (1) and (2) from Canada's analysis correspond with the points (1) and (2) from Denmark' analysis, however the points (3) and (4) do not correspond with (3) and (4) from the Denmark's analysis. The next question that is important to answer is whether the end result will be the same if in Canada points (3) and (4) change in the near future correspond to (3) and (4) in Denmark. Assuming that this condition get satisfied in the near future, will that be enough to have in Canada the same work-life balance Denmark has?

From the report of Duxbury & Higgins, 2013, it is obvious that the perceived flexibility of the Canadian employees regarding working from home as well as their willing to bring work home is outstanding compared to the perception or attitude that Danes had. This condition alone is enough to conclude that the application and implementation of the current Danish Workplace Model would not succeed in Canada because Canadian employees have a different perception of their work and flexibility compared to Danes.

This paper showed that the way individuals consider the concept of work in the countries of Canada and Denmark are quite different. Canadian workers in general are not averse to bringing work to their homes. The work day in Canada does not end upon leaving the office. It is actually seen as a badge of honour to be completing work at home. Employees in Denmark tend to be more demarcated in their view of where the workplace ends and the home begins. The barriers are much more defined. Although the similarities in working conditions were many and fascinating, the culmination and comparison of the work life balance was that the perception of the division between the workplace and the home is more rigid in Denmark. Consequently, it proved to be difficult to show that the Denmark model could be successfully applied in Canada.

The analysis of this report was limited by the historical and statistical information available and obtained within the timeframe allowed for the research. The historical information and the statistical conclusions were bound by the feedback provided respectively by the reporters and individuals.

The report assumed that both Denmark and Canada had similar or the same rates on Education, Jobs and Environment scores because the OECD rate numbers were very close. However, due to the research time constraints such assumption was not investigated and confirmed.

Also due to time constraints, the research did not analyse whether the promotion and implementation of work-life balance approaches and flexibility in Canada could have a positive impact on the employee's perception of his flexibility that affects his work-life balance.

Since the research deducted that there are differences in perceptions of work and flexibility between Canadians and Danes, and that the application and implementation of the current Danish Workplace Model may not have a complete positive outcome in Canada, it will be interesting to research the question of whether the promotion and implementation of work-life balance approaches and flexibility in Canada could have a positive impact on the employee's perception of his flexibility, which affects work-life balance.

Further consideration will be to study and plan the nationwide implementation process of work-life balance in the Canadian culture.