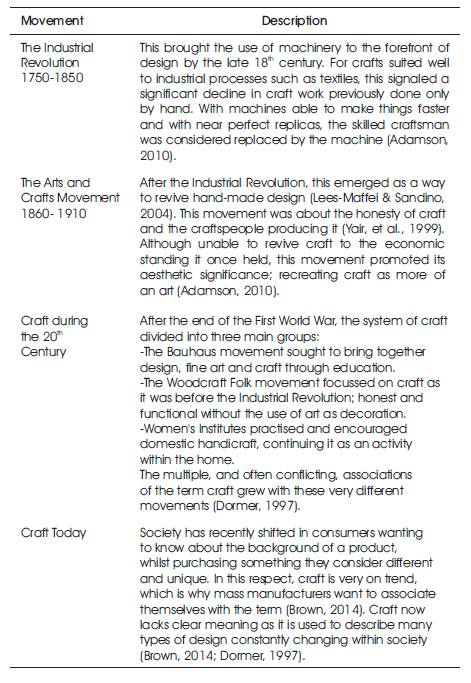

Table 1. Craft Movement

This study investigates how far current perceptions of craft could influence consumer values and purchasing behaviours of products; first, considering the value of craft itself and preconceptions which may be held of it, and second, investigating its viability to improve consumer values when used within mass manufactured products. The article examines what this could mean for the future of craft, and to what extent it could affect the mass manufacture industry. Literature briefly examines the history of craft, before considering its current position within society with reference to how it is defined and its associated preconceptions. Examples of craft used within mass manufacture are explored, with consideration to the extent of its feasibility and what this means for the craft element and resulting mass manufactured product. A consumer survey was carried out to establish current values people associate with craft and mass manufactured products, examining whether any personal emotions or preconceptions are held by the majority. Interviews were additionally carried out with two professionals within the craft and mass manufacture industry, each with over 15 years of experience in their specific field. An interview was also carried out with a consumer, to gain a more indepth perspective of their personal associations of crafted and mass manufactured products. The results from the interviews and survey section both strongly support that craft holds particular value with consumers over mass manufactured products, due to the human connection it creates from the link it holds to the craftsperson.

With current mass manufactured products lacking consumer value, this can lead to a high-turnover of products and a throw-away society.

The current study aims to consider how far the inclusion of craft within a product can have an influence on consumers. This will analyze if craft holds emotional value, whilst exploring if consumers have preconceptions of what craft means to a design. This aims to provide an understanding of how far including elements of craft within mass manufactured products could be viable, in order to improve user perceptions of them. In turn this could address the issue of creating valued consumer products.

The study achieves this through analysis of existing literature, followed by conducting primary research with both consumers and industry professionals.

From this, the study also aims to consider what this means for the future of craft, and how the role of craft may affect designers and mass manufacture in the future.

To understand how craft may impact future design, it is important to briefly understand how craft has influenced society in the past up to the present time, see Table 1.

Table 1. Craft Movement

The aim of this study is to explore the perception of craft and how far it is valued by consumers within products, whilst considering if within mass manufacture there is a place for craft which could influence its future use.

The objectives are as follows:

The Research Questions taken for the study are as follows:

The literature review aims to provide a background into what is meant by craft, whilst analysing its perception within society. The role of craft within mass manufacture and whether it has a place here will be examined, before considering what this means for the future of craft. The literature review will achieve this through research into journals, internet articles and books to help answer the research questions.

Craft is a process of products being designed and made through the hands of the same individual (Campbell, 2005; Crafts Council, 2011). Frayling (2011) defines this as highly valued skilled labour. Additionally, knowing and understanding a material through the senses makes the definition of craft more than just made by hand, but rather as truly understood on a deeper level by the craftsman (Nimkulrat, 2012).

Until the end of the 19th century, 'handicraft' instead described the craft of this era (Dormer, 1997). Handicraft, shortened to craft, at one time would have referred to products made entirely by hand, or by machines very much powered by the person; such as a potter's wheel (Campbell, 2005).

However, commonly craft is seen to have no straightforward meaning, as it spans over time and nations to mean different things to different people, with many referring to it as they deem fit for their purposes (Dormer, 1997;V & A, 2015). Craft can be seen from traditional hand-powered processes through to contemporary craft; where products are made by designers creating new processes with new materials (Campbell, 2005; V & A, 2015).

Between the 19th and early 20th century, a crafted product was traditionally perceived by consumers as one which humanised products due to the labour involved. The mass-manufacture movement automated previously valued processes requiring human skill, which in turn dehumanized products (Campbell, 2005). Bonanni, et al. (2008) supports this, stating that mass manufactured products are generic, caused by designers now often being so distanced from the making process.

Craft can create a sense of humanity within consumers when interacting with crafted products. People relate to imperfections or differences between every design as a natural human trait; providing them with a sense of validation as a human being (Needleman, 1993). The Design Council (n.d.) supports this, suggesting crafted products provide consumers with a sense of identity, the saturated market of commercialised products cannot.

Additionally, the term craft holds an ideology. People perceive objects created in industry as separate from objects created by the skill of human hands. This creates feelings of detachment and a loss of something human when consumers consider industrialised products. It is considered craft will always distinguish itself from industry, as it has care and time within its making unachievable within mass manufacture. For a product to be made by one person, for another, holds emotional significance with consumers (Crafts Council, 2011).

Emotional significance is also increased as a crafted product can fit the ideals of the consumer; either through aesthetics, values or the human connection associated with the product. This “human-product relationship” allows the consumer to build and attach emotions more easily to crafted products, making the object personal to them (Kalviainen, 2000, p. 5).

Consumers also have the predetermined view that the skill and emotion of the designer resides behind the physical object produced; which in turn gives it value. Deeper social values are suggested to define craft from other design trends, such as personalised or customisable products (Campbell, 2005). Duray, et al. (2000), however, argues the addition of craft to mass manufacture can be considered mass customisation.

Similarly, consumers also associate craft with quality, with the suggestion that brands use it to suggest a product of value (Crafts Council, n.d.). It is suggested consumers also perceive craft to be expensive in relation to this high quality. Crafted products have not only preconceived emotional value, but also financial and cultural values. A particular group of consumers, generally wealthy with “cultural capital”, are suggested to seek out and purchase crafted products (Campbell, 2005).

Craft can have many different meanings associated with it. However, many people may only know the traditional view, as suggested by Campbell and Frayling, of craft as a representation of handmade products, not one industry can implement on a larger scale (Frayling, 2011; Woolley, 2011).

The Crafts Council (n.d.) argues that an approach must be taken to add value to mass-manufactured products, as inexpensive and high turnover products lack consumer value. Woolley (2011) supports this, suggesting presentday crafting methods are the best way to achieve mass manufactured product value, as opposed to just seeing craft as a separate traditional skill, see Table 2.

Table 1 suggests some hand-craft elements have the possibility of being realistically introduced within mass manufactured products where they most closely align; for example through the craft element of hand machining (Woolley, 2011).

Oakley (2009) suggests craft will, however, always aim to distinguish itself from mass manufacturing, as it adds a personal element not achievable through mass manufactured products. The product created is less important than what the craftsperson behind the product means to a consumer. Through purchasing crafted products, consumers can convey themselves and their own values to society.

Craft is argued to hold social value from the ideals of it having a cultural background as something made by a person. To consumers, this is something which cannot link to industry, as it lacks the authenticity of a design created by a person (Dormer, 1997).

The need for distinction between craft and industry is argued for, as craft once encompassed people making high quality objects skillfully by hand, yet today describes products within industry which though may be highquality, are actually machine-made (Risatti, 2007). This contradicts Woolley (2011), who determined handmachining within the realm of craft, and thus perceived it allowing hand-craft to be introduced into mass manufacture.

Within mass manufacturing garments, meeting consumer demand for high-end crafted garment qualities is hard, as it is difficult to quickly provide changes in design without moving away from mass manufacture processes (Collins, 2001). Table 1 clarifies, craft inherently relates to low amount of goods produced with lots of variety, compared to mass manufacture, where high amount of goods are produced with little variety (Brown & Bessant, 2003; Woolley, 2011).

However, some mass manufacturers can include elements of craft through skilled and independent workers. Additional craft elements applied to mass manufactured products allow garment industries to successfully produce the craft quality desired by the consumer, without losing their mass-manufacture methods. Within fashion, using “craft-like production regimens” makes craft additions possible for the product to have the craft value associated with it; previously only known by small specialist designers (Collins, 2001, p. 166).

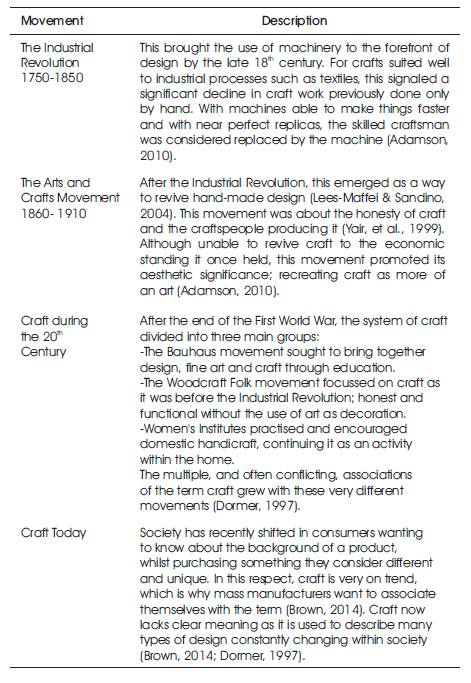

Figure 1 compares the characteristics of craft to mass production processes, showing as processes become more suitable for manufacture, they gradually lose physical human involvement (Woolley, 2011).

Figure 1. An Expanded View of Craft-related Activities (Woolley, 2011)

Woolley (2011) argues adding craft elements to handfinish mass manufactured products should now be considered part of crafts terminology, as craft has developed far past when either craft alone was the method of manufacture, or to the time when the Industrial Revolution created the divide between craft and mass manufacture.

Elements of craft, some mass manufacturer's state their products have; however, are argued to be only the image of craft. Phrases such as “'hand-made', 'hand-finished', 'made by our craftsmen', 'uniquely for you'...” appeal to consumers, but do not always truly make products crafted (Frayling, 2011, p. 2).

Industry case insights suggest including craft elements does not always reflect their true values. Figure 2 shows American clothing company Levi, whose global 'Craft work' campaign included a team of craftsmen and women who formed the face of the brand to reiterate its history of craftsmanship. This campaign reflected past values of the company more than current ones, showing an advertising scheme to attract attention from consumers instead of concerning the real craft of their product (Frayling, 2011).

Figure 2. Levi Craftwork Campaign (What a Royal Idea, 2010)

However, Woolley (2011) argues crafted elements within luxury product production, such as this, are one of the most successful current ways which craft is influencing in mass manufacture.

Current debates exist within the garment industry over whether craft principles are a great enough influence on the success of a mass-manufactured product (Collins, 2001).

However, it is argued that craft represents such value to society and culture that it will only develop further in its future use within mass manufacturing. This could develop past methods such as hand-finishing mass manufactured products with craft elements, as new materials worked with through advances in technology develop more feasible methods for using craft within mass manufacture (Woolley, 2011).

The availability of information over the internet allows craft skills to be easily accessed, shared and developed within "new kinds of digital craft communities" (Bonanni & Parkes, 2010, p. 180). Craft skills and knowledge shared freely through this worldwide source will be the future of how craft continues socially; in some cases helping regenerate crafts otherwise forgotten (Bonanni & Parkes, 2010).

Adamson (2013) opposes all areas of craft which would suit being introduced within mass manufacture. When considering wood carving, even modern machinery is unable to create the intricate designs a craftsman is able to within solid wood.

On the one hand, craft directly opposes modern design (Adamson, 2013). There is concern that digital design is replacing the practical craft of making products by hand (Brown, 2014). However, Adamson (2010) supports that new technology, in forms such as the internet and rapid prototyping, are influencing how craft fits within current society. Processes such as 3D scanning can work alongside craft; with laser scanners in Italian cobblers allowing craftspeople to create bespoke shoe designs for individual customers (Bonanni, et al., 2008).

Modern digital technologies could be a craft in themselves, as craft is defined as the manual activity of skillfully creating something. Therefore, the complexities of 3D printing could be seen as craft. It is argued that crafts’ definition does not oppose it advancing with current society to link with new technologies and processes (Brown, 2014).

Craft is associated throughout the literature as a design process involving human skill. The articles, however, do not agree to what extent human skill must be involved for a process to be classed as craft. Although the literature cannot agree on a clear definition for craft, it demonstrates how far the term craft is used to describe very different processes.

It can be concluded that craft is associated as personal and sympathetically human; with emotional value created from the connection it has to the skilled craftsperson that made it. The preconception of crafts’ expense relates to the perception of it being of highquality. The articles suggest these preconceptions make craft more desired by consumers.

The preconceptions associated with mass manufacture, however, completely contrast to those held of craft. Consumer detachment to inexpensive and high-turnover products suggests mass manufacture which requires more consumer value associating with it, which could be achieved through the addition of craft elements.

To some, applying processes such as hand-finishing and hand-machining to a mass manufactured product can allow crafted to be used in its description (Woolley, 2011). However, others argue craft is fully making a product by hand without the use of machinery (Risatti, 2007). The literature suggests the definitions of craft conflict as they come from many different eras of design, each with their own take on what craft was and should become.

The information gained from the literature review provides an understanding of the varied opinions associated with craft and mass manufacture design.

Primary research was gathered through the use of interviews and a survey to provide a current realistic view, from both consumers who purchase craft and professionals who make products, on what this could mean for the future of craft. The results can also be compared to see if consumer and professional perceptions surrounding craft and mass manufacture align.

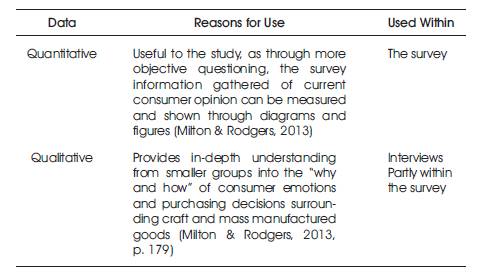

Qualitative and quantitative data provide different ways to collect and analyse information gathered from different research methods, see Table 3.

Table 3. Data Types

Both types of data collection methods are important to provide detailed primary research, addressing the most current perceptions of craft not covered by the secondary research (Robson, 1993).

This study concerns any consumer who purchases products, not limited by factors such as age or gender. Therefore, gathering data quantitatively through the survey was a simple yet easy way to target a large proportion of consumers. Although surveys can have the issue of limited responses, making it available to a larger group of people than needed through social media addressed this, allowing a suitable amount of responses to be collected (Milton & Rodgers, 2013).

The main disadvantage of surveys is the inability to ask further questions in response to answers given. However, this time-consuming level of in-depth analysis was instead achieved through conducting interviews (Milton & Rodgers, 2013).

Mainly using fixed-response answers made the survey easier and quicker for consumers to complete. Two openended written response questions provided additional indepth understanding the researcher had not expected, on why consumers felt about crafted products as they did, without the survey taking too long to complete. Links could also be drawn between correlating answers to provide qualitative data (Milton & Rodgers, 2013).

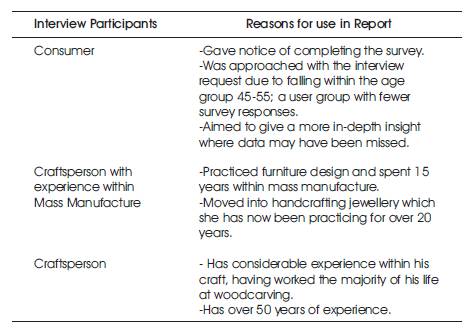

The pros and cons of interviews are given in Table 4. Interviews were conducted with a consumer and two professionals within craft and mass manufacture, providing in-depth qualitative data through the simple, but effective process of asking (Milton & Rodgers, 2013).

Table 4. Pros and Cons of Interviews

Focus groups were considered to gather a larger range of qualitative data more quickly from consumers. However, a group environment can be hard to share emotions in, sometimes resulting in dominant participants whose views others may not want to contradict (Evalued, 2006).

A semi-structured individual interview provided the best method to gain in-depth information into participant emotions and opinions surrounding a products design. This ensured the main questions requiring answers were covered, whilst allowing for some unstructured input to provide opportunities for unexpected insights to be found from both the consumer and professionals. Visual of the participants also revealed further emotions in response to the questions (Milton & Rodgers, 2013).

The survey was piloted with a test user to ensure information gained would best inform the study. Initial questions, included a comparison of crafted and noncrafted product images, which did not provide enough usable information to inform the study. Therefore, this was replaced with a likert scale style question, from which results could be more easily and usefully analysed.

The main disadvantages to interviews can be their running and set up time. Therefore, piloting the final questions, was essential to avoid wasting the interviewer, and interviewees, time (Evalued, 2006).

The survey aimed to understand current values consumers associate with products, to see if a majority view of terms such as personal emotions or preconceptions, surround craft.

35 participants answered the survey, ranging within different age groups and income brackets. A near even split of approximately 57% men to 43% women answered, however, a far higher proportion of 18-24 year olds responded compared to anyone above this age. This linked to the income question, where the majority of people answered 'N/A (Student etc.)'. The survey being mostly answered on social media, generally used by a younger population, could have influenced this.

The results showed all participants had purchased handcrafted products, or products with craft elements in, for themselves or someone else.

When asked whether including craft elements or handcraft increased people's desires to purchase crafted products, 94% of people answered it did. The majority of views associated crafted products as being more personal, which in turn makes them more special. The time, effort and skill of craftspeople were on the whole valued, with some answering that this gives the product a human connection to consumers which mass manufactured products do not.

Though the question did not ask participants to compare craft to mass manufactured objects, a third of comments stated they would rather purchase craft over mass manufactured or machined products. One user answered that even though they knew a machine could produce objects far better than a person, they would still rather buy handmade products.

Only 6% of consumers argued against craft increasing their desire to purchase a product. One argument was that if a products’ price or quality was impacted from it being crafted, then it could persuade them to purchase mass manufactured products.

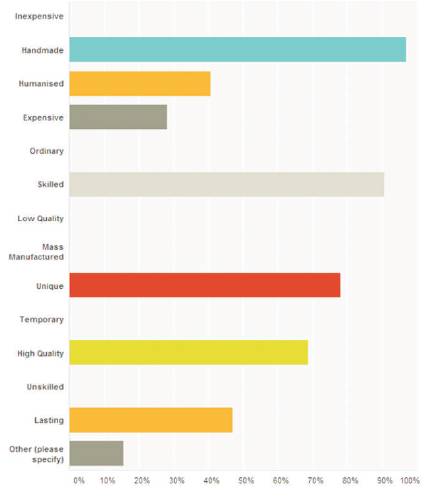

As Figure 3 shows, when participants were asked what they are associated with craft; handmade, skilled and unique overall were the most chosen options.

Figure 3. Survey Question 6

Terms associated with design normally in a negative way, such as ordinary, low quality, temporary, and unskilled were chosen by no participants to describe crafted products. The general view showed craft as associated with a positive image; such as being a skilled or unique design. Although of the options chosen it was chosen least, nearly a third of participants associated craft as being expensive.

Although a survey note prompted consumers to consider craft elements included within mass manufactured goods when considering products, no participant associated mass manufacture with craft in this question.

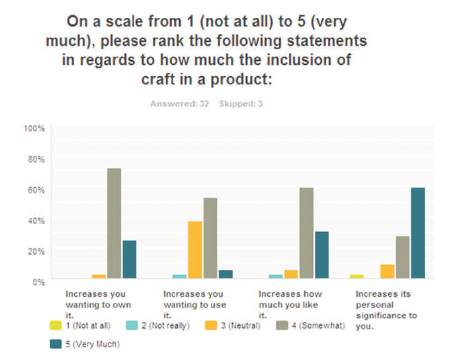

A likert scale question, Figure 4, aimed to see if there were correlations between consumer views of how the inclusion of craft affected product perceptions.

Figure 4. Survey Question 7

The first question asked participants how far the addition of craft increased them wanting to own a product. The majority of people stated 'Somewhat', followed by 'Very Much'; showing craft to quite significantly increase consumers wanting to own a product.

The second question asked participants if craft within a product increased their wish to use it. Although the majority stated 'Somewhat', this was closely followed by a nearly 40% 'Neutral' view. Usability was thus least associated with consumers increasingly wanting to purchase craft.

The third question asked how far the inclusion of craft increased a consumer liking a product. Craft quite significantly increased like ability, with 60% answering 'Somewhat' and 30% 'Very Much'; with only 10% having a view of 'Neutral' or 'Not Really'.

The last question, however, gained the most positive responses, with 60% of consumers stating the inclusion of craft 'Very Much' increased a products’ personal significance to them. Nearly 90% of consumers stated 'Very much' or 'Somewhat' to this question, showing personal significance as the greatest association consumers have with crafted products.

When consumers were asked if they owned a product with craft elements which they particularly valued, the majority of people at 75% said yes, and gave the example of what this was or why this was the case. The view most commonly held by consumers of why they valued a particular crafted product was because they had met, or knew something of, the designer behind the product. In some cases, this was also accompanied by the consumer knowing about the process the product was made by, such as through a traditional crafting technique. Other mixed views such as craft making the product unique to the person, or of it holding personal emotions of a time and a place, were also mentioned more than once. One consumer in particular explicitly stated that the imperfections of the handmade object they owned gave the product a human connection.

The interviews aimed to gain background information from professionals within craft and mass manufacture about the subject they practice, their perception of craft, and their opinions on craft within mass manufacture. This helps show what professionals within relevant industries believe the future of craft will be.

The designers interviewed both agreed their craft held value to them as the designer maker. The designer experienced in both fields left mass manufacturing furniture as she wanted to be more creative and passionate with her designing; which was not possible within a workplace of "production lines and deadlines".

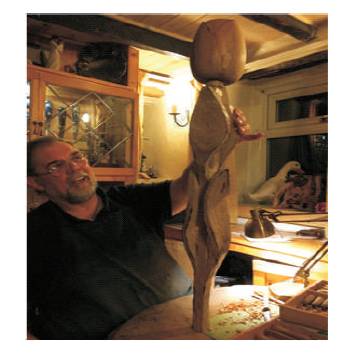

Similarly, the woodcarver gets extreme pleasure and excitement from his craft. Only if someone is happy with commissioned work will he allow payment, as he gets as much enjoyment from giving the finished product to a pleased customer, as he does from making it; shown through Figure 5.

Figure 5. Craftsman Woodcarving (Vaines, 2015a)

The craft and mass manufacture designer explained that within industry, using the term crafted to describe a mass manufactured product gives it a selling point. She suggests mass manufacture often has bad media associated with it, which means even when a product is mass manufactured; companies do not want to label it so. Crafted products are perceived by consumers to be of a higher quality and more special than mass manufactured products; which she suggests makes the consumer feel special to own them. Both designers agreed that associating a mass manufactured product with hand-craft, even if the hand-craft element is only nominal, helps companies sell a product.

However, when considering whether craft can realistically be included within mass manufacture, both designers did not believe this could truly be achieved. Although the craft and mass manufacture designer explained the technique used by the company she had worked for, she did not necessarily agree with it. She identified the only craft element of the bespoke factory furniture production she had worked within was hand-forming the upholstery and springs onto the sofa. The frame, material, and all other components were externally mass produced and bought in. In her opinion, this product could not mostly be promoted as crafted, as too many mass production elements were used within its design.

Additionally, the woodcarver suggests mass manufactured goods are often referred to as handcrafted in order for companies to increase their prices and sales. He argues that consumers not experienced within a subject area can be misled into what they believe is handcrafted in a product.

With the designers interviewed, the agreed issue was not hand-craft elements being included within mass manufacture, but that they are not explicitly explained as to how much they are part of a mass manufactured design; often being far less than the high price tag implies.

Although the woodcarver believed to some extent, no machinery should be used in anything referred to as hand-crafted, there was a consensus between both designers that the majority of the work within a product referred to as being crafted, should actually be handcrafted.

However, the woodcarver argues what hand-craft is, can be up for interpretation. In his opinion, someone handling a machine is not a hand-craft process. On the other hand, the craft and mass manufacturer considers the elements mass produced to matter more, such as a hand-crafted earring being acceptable as handcraft if attached to a mass produced ear-wire.

The craft and mass manufacture designer also suggests in reality, having experienced the significance cost plays within mass manufacture, the two cannot overlap. She argues that for the majority of elements to be handcrafted within mass manufacture would be completely unfeasible.

This is supported by the woodcarving craftsman, who states that to make what he does into a business would spoil it. It requires time to get his work to the detailed standard he does. If people were to pay per hour for what he creates they would not be able to afford it; half of what he does is for the love of his craft.

Both designers believe computers will play an important role in crafts future, however, in different ways. The craft and mass manufacture designer suggests socially the internet will provide a way for information to be shared and continued even when it is no longer being passed down through families. Commercially she argues that normally all design will start as handcraft, before it is modified to meet demand through mass manufacture.

The woodcarver argues that although crafts like his own may be fading due to less people learning them, current processes requiring skill could be seen as types of craft in themselves. He considers that although it may be someone working through a computer, such as a film animator, if it requires skill not just anyone has, this could be seen as a type of craft.

The interview aimed to gather a more in-depth consumer perspective of craft and mass manufactured design than could be achieved through the survey.

The interview highlighted that to the consumer, a crafted product holds far more personal significance. The consumer connects the finished product with presumed emotions and a story of the craftsperson behind it. They associate the product with the idea that the craftsperson must love their craft for them to have practiced and become an expert in it. To them, that is what makes craft special.

There was also the preconception that mass manufactured products have perfection within their design unachievable within crafted products. However, this was seen negatively. The consumer associated a product being faultless every time as lacking human qualities. There was also the idea that imperfection can become a marker on a crafted product, signifying it as the users own.

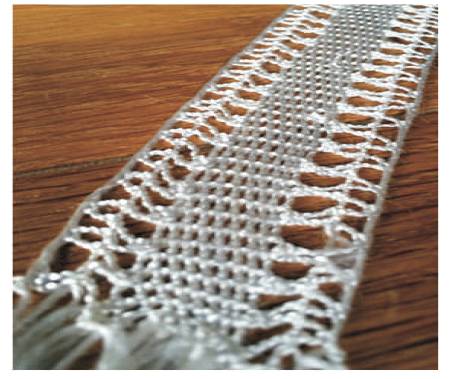

The consumer owns several crafted products and for each she knows something about the process through which they were made. For the lace bookmark in particular, seen in Figure 6, there is the image in the consumer's mind of it being made by a process dating back hundreds of years. It also links to a place which holds memories for herself and her family. However, the consumer did not believe the product just held significance due to who had bought it for her and memories associated with the place it came from. Instead, she associates craft as being something you both take time choosing when you are the gift giver, and take special pleasure from when receiving. In her opinion, a crafted product is not one that is required as a need, but rather as something which is emotionally meant to signify more in its choosing.

Figure 6. Lace Close-up (Vaines, 2015b)

This concept is clarified when the consumer discusses preconceptions she associates with both crafted and mass manufactured products. When describing whether handcraft itself holds value, the consumer referred to mass manufactured products as being designed for maximum quantity, at the smallest cost possible, in the least amount of time. This was held negatively by the consumer, who considers mass manufacture to be just about financial gain. However, she does not associate financial gain with handcrafted products. In describing a handmade necklace she owns, the consumer elicits as to why this may be. The consumer got to know something about the craftsperson behind the necklace, describing how jewelry making helped him overcome insecurities he felt over a disability he suffers with. This gives an example of an emotional gain for the crafter behind the design, which holds more value with the consumer.

To the consumer, a crafted product is something made with care, which separates it from being just another product of many in existence. When the consumer argues it is harder to throw away a handcrafted product, she suggests this is because people cannot detach the human maker from the product.

The consumer associated craft as being unfortunately expensive. However, she also suggested if she was able to afford craft to the point that she could buy it all the time, she did not believe she would appreciate it as much.

The results of the empirical data clearly show, from views held by both consumers and professionals, that craft holds value within current society.

The human connection a crafted product has to its maker holds particular value with consumers; who see the skill, time and passion of the craftsperson reflected in the product. The consumer survey and interview results both agree craft is more personal to consumers when they know the person or process behind its creation, as it signals a product made with care by someone who truly loves their craft. Emotionally, these perceptions hold a lot of value, as when a product can create personal significance as craft does this suggests it cannot be easily discarded.

Consumer perceptions of there being value behind a crafted product from the maker are well-founded. The industry professionals interviewed showed passion, excitement and a love for their craft not based around financial gain. The woodcarver not charging accurately for his time to enable people to afford it, and refusing payment unless the customer was happy shows his work is personal to him.

With the highest proportion of consumers at 95% choosing 'handmade' to describe craft, and both professionals stating that anything referred to as hand-crafted should be predominantly made by hand, this suggests people expect something referred to as craft as being predominantly made by a person.

No consumer surveyed associated the term mass manufacture with craft, even when prompted to consider products which may be mass-manufactured and finished with craft elements. Consumers associate mass manufacturing as products designed for maximum quantity at the smallest cost, in as little time as possible for the highest financial gain. Consumers, when just questioned on craft, used mass manufactured products to describe why they value a crafted product so much more; with a third surveyed stating they would always rather buy craft over mass manufacture. This showed mass manufacture to be perceived as the complete opposite to what defines craft.

Even when consumers knew products could be made better by a machine, craft was valued more. The consumer survey and interview stated perfectly replicated designs, associated with mass manufactured products, lacked human qualities.

The results showed that to consumers, the inclusion of craft greatly increases a products’ personal significance to them over it increasing their desire to use the product; showing craft is bought mainly for personal reasons, over practicality.

Craft is understandably associated as being expensive, both from the consumer and professional point of view, due to a person making something by hand with skill built over many years of learning and practicing. However, that it was not the most chosen thing to describe craft; shows craft holds associations of greater value with consumers.

The results show there is no straightforward meaning for craft, as it often means different things to different people (V & A, 2015).

If the wood crafters view is taken that to refer to craft, the majority of the product must be handmade without machinery, then the type of craft he creates would not work within mass manufacture. However, he also suggests craft is about skills held by people, and so it could span over many types of human-powered design. He again links to ideas from the V & A (2015), in considering craft in the future could involve new technologies and materials.

Craft is often defined as falling within or outside the term handicraft, where products are made through what is seen as traditional hand-made processes; such as would describe the woodcarver's craft (Campbell, 2005). However, other types of craft, involving machinery or more modern processes, are often referred to as crafted or having craft elements (Woolley, 2011).

This suggests handicraft separates itself from other craft styles, however, does similarly not prevent them being types of craft in themselves. As craft means to skillfully make things by hand, this does not oppose design progressing and areas such as 3D printing, requiring people skilled in using the machinery, from being seen as a type of craft (Brown, 2014). However, the valued products described by consumers only appearing handicraft made, suggests this to be the most valued and known style of craft currently.

Craft not being associated with mass manufacture in the surveys or interviews shows even in this current era, when craft is meant to be influencing mass manufactured products, consumers still see it as a very separate process. Considering the high proportion of design students likely to have answered the survey, who should be aware of design movements and current trends, it was still not chosen. This suggests even if craft is being included within mass manufacture, it has not yet made significant consumer impact.

Mass manufacture is constrained by deadlines and the constant aim of increasing product sales; as described by the professional experienced within industry. The upholstery forming within the bespoke sofa making shows craft existing within mass manufacture. However, although forming involves a skilled craftsperson, it remains a very small part of a far larger manufacturing process, and in some respect, sales technique. Mass manufactured products are often associated with bad media, as shown by negative consumer views of them, which they want to separate themselves from. Primary research indicates mass manufacturers knowingly include craft as an angle to sell something, as they know consumers consider craft to be more special (Crafts Council, n.d.). As consumers most negatively associate mass manufacturing as being about financial gain, if consumers knew a product included craft solely for profit, it would appeal far less on an emotional or personal level.

Mass manufacturers can mislead consumers, as suggested by Frayling (2011), when referring to the extent craft is used within a product; including far less craft than consumers expect based on its price, with far less human input. Misleading consumers through craft elements to increase manufacturer profits could risk creating negative associations with any elements of craft included within mass manufacture in the future.

Mass manufacturing will always lack the person and deeper emotion behind a design which consumers relate to (Nimkulrat, 2012). Craft is about the passion of the crafts person shown through a skilled design which has taken time to create; something which cannot feasibly be achieved within mass manufacture. If craft is allowed, the association of being hand-machined, as suggested by Woolley (2011), it can be more practically included within mass manufacture to create simpler designs with variety at quicker speeds. However, with actual hands-on intricate making such as the woodcarver practices, and such as most consumers describe their valued products to be, this cannot work within mass manufacture. There is a limit to what is achievable, and because of this the crafted element within mass manufacture may not be as highly valued within a product.

The very human trait shown by the woodcarver of being paid less to ensure people could afford his products would never be shown in mass manufacture, as its main aim is to produce profit, and cannot emotionally sympathise with people. However, if people feel connections to their objects, they value them more with imperfection seen as a very relatable human trait often valued about craft.

With anything corporate, such as mass manufacturing, value and significance is lost through associations of it being widespread and common, as opposed to unique and special as craft is normally associated with (Oakley, 2009). Therefore, this could influence the effectiveness of trying to include craft within a mass produced design to increase its consumer appeal.

The results show craft is less desired for its function, as it is not bought for practicality or need, but rather for personal reasons. Consumers see both giving and receiving a crafted product have far more significance and emotional meaning than just another mass manufactured product (Crafts Council, 2011). There is a sense of moving away from the practicality of modern life when considering buying craft just for its emotional significance, not for a practical purpose (Oakley, 2009).

Craft is known for being understandably expensive due to a person making something by hand with skill built over many years of learning and practicing. This is shown by the woodcarver not truly reflecting the hours or skill in his prices so people can afford his products, which in current society only those of wealth, as suggested by Campbell (2005) , would be able to afford. However, the negative associations of mass manufacture, such as maximum product quantity at the lowest cost, have created affordable products allowing people the necessities for a good living standard. Craft is not the necessity it once was and so is now deemed a luxury product. This implies that for consumers, the cost and fact it is not something normally or casually bought, gives it more value when it is.

Including craft within mass manufacture could make it more accessible in part to consumers, as realistically a product not entirely handmade should be more affordable. However, the mass manufacture professional stated even when a bespoke piece was mostly mass manufactured but was hand-assembled, it was far more expensive than a completely mass manufactured piece. Craft within mass manufactured goods, as suggested by Frayling (2011), is often only a small element of the design, but can add significant cost to a product. As suggested by the woodcarver, expense is something consumers associate crafted as being, which can mislead them into believing a product is worth a price for the level of craft within it, which is not often a fair representation.

If mass manufacture made craft more affordable, it may hold less value with consumers, as this expense is now linked with the luxur y of craft. Therefore, mass manufactured products with craft elements may always hold less value than a fully crafted product, if the price to craft amount is truly reflected.

Craft is defined as objects skilfully created by hand, meaning its definition can cover craft created with the use of no machinery from before the Industrial Revolution, through to modern crafts created using new technologies such as 3D printing today.

However, there remains a distinction in how products created purely by hand are most valued by consumers. The essence of handicraft will always define it from other styles of craft in the future. The emotional link to a person practicing a skill centuries old holds a consumer ideal, with products seen as unique and special within a society of predominantly mass manufactured objects.

Crafted products hold the most value with consumers as they can achieve a human connection. Preconceptions of skill, passion and a product sympathetically human in its lack of perfection create an emotionally valued product. Its associated expense prevents purchase often; however, when purchased this means it holds even more significance, preventing it being easily discarded.

Currently, craft is more commonly being implemented within the mass manufacture of garments and furniture. However, only small elements of craft can realistically exist within a mostly mass manufactured product, as this industry is required to function with fast and inexpensive processes.

Craft within mass manufactured products has shown to increase product value, however, indications are this is due to consumers not realizing, or being purposefully misled, in how much craft is within a product. With its main use being to increase financial gain, over trying to create consumer products with longevity, emotional values consumers hold surrounding craft could be less within mass manufacture.