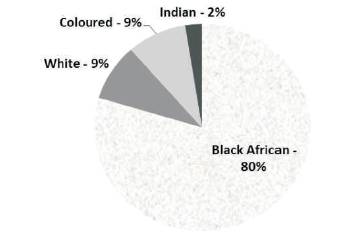

Figure 1. Racial Composition of South Africa

Trying to understand the South African population can be a tricky and time consuming exercise. As a country, South Africa has a significant cultural diversity and the large size of the country leads to considerable variation within the population, which demands inventive and careful analysis when determining key traits. This paper is aimed at developing a better understanding of the South African consumer and their behavior patterns as well as potential methods to use this knowledge to better reach and influence behaviors.

Due to diversity along demographic, geographic and cultural lines, assigning traits and characteristics through traditional segmentation tools proves to be particularly challenging. Through the integration of established marketing tools and innovative segmentation techniques, a better understanding of the motivators and drivers of behavior behind certain segments of the population was attained. Amalgamation of existing research based on value dimensions and industry specific market materials provides a better comprehension of the various divisions specific to the South African market and the South African consumer

While making for an interesting population, diversity can be the cause of many organizational challenges. Baldwin & Huber (2010) concluded that increases in Between Group Inequality (BGI) can lead to poor economic performance in those countries. It was also noted that South Africa is one of the countries in the world with highest BGI which is further confirmed with its current GINI (income distribution) index of 63.1, ranking it currently as number one in the world (World factbook, 2013).

Diversity within the South African population stems from the wide variety of historical ancestry of its citizens. South Africa is comprised of four predominant racial groups namely Caucasian (mostly of French, Dutch and English origin), Black African (including tribal backgrounds of Zulu, Xhosa, Pedi etc.), Coloured (a heterogeneous ethnic group with diverse ancestral links including Caucasian, indigenous Khoisan, Indian and Malaysian to mention a few) and Indian (See Figure1). Along with ethnic differences, South Africa has 11 official languages and has a strong Christian, Islamic and African traditional religions (World factbook, 2013). Sixty-two percent of South Africans live in urban areas (World factbook, 2013) and there is a trend for migration from rural South Africa to these urban areas (Statistics South Africa, 2012) .

As illustrated in Figure 1, South Africa is both economically and culturally divided. This, along with the psychological and infrastructural legacy of its Apartheid past; where certain groups were denied access to specific amenities1 has led to many challenges in understanding the population and the application of optimal marketing strategies. Social sensitivities and cultural ethnocentrism within the country serve as both obstacles and great sources of creative opportunities in the South African market (Shaw-Taylor, 2008).

Figure 1. Racial Composition of South Africa

Personal values play a central role in the behavior patterns in human beings and these values also promote coherence across multi-cultural lines. Values determine needs and perception and can also influence preferences. Therefore, to understand national culture, an analysis of the value orientation of the population is imperative. Schwartz (1992, 2006) identified and classified values which are applicable to various cultures globally. The remainder of this section will use this theory of cultural value orientation to better understand the national culture of South Africa.

Schwartz (2006) identified three conflicting themes which are present in all populations. Firstly, the conflict between autonomy versus embeddedness is a measurement of the boundaries between an individual and the group. A society which is rated as high on the embeddedness index would perceive an individual as one part of a whole, versus an autonomous society, where individuals pursue goals independently of a group. Secondly, critical issues relating to the maintenance of social behavior and control for the assurance of responsible behavior in society is addressed. The polar solutions are labeled as egalitarianism (where individuals recognize each other as individuals and hold similar values and moral expectations) and hierarchy (where a 'top-down' approach is accepted as a solution for maintaining and enforcing responsible behavior). Finally, issues such as how people relate to their environment - natural and social - are met with a response of either harmony or mastery. When a society is ruled by harmony they react through trying to understand, and find a way to form part of the environment as peacefully as possible. Conversely, when a population reacts with mastery, change to the environment ensues with a great focus on attainment of personal goals.

When assessing South Africa in these terms (Schwartz, 2006), the country scores high in embeddedness and low on both intellectual and effective autonomy. Thus it can be deduced that issues where personal orientation is challenged, South Africans prefer to act according to group norms i.e. behave 'properly', follow rules and are less likely to act independently or out of personal interest. A relatively high score is also obtained on the hierarchical segment, therefore, it can be said that the general South African population requires or prefers behavioral direction from an assigned body such as a community or national leader.

Swartz's findings associate well with the South African ideal of Ubuntu. Ubuntu is a spirit of living which is widely accepted within African cultures. The philosophy of Ubuntu is described as having the following characteristics: Socialization of prosperity – where good fortune is redistributed to the community, Redemption where deviant behavior of an individual is perceived as the result of his community and thus that society should always look to redeem him/her (Magolego, 2013). Deference to hierarchy and humanism are two characteristics of Ubuntu which link up directly to the hierarchical and embeddedness values of Schwartz and further confirm the applicability of his findings.

As already noted, South Africa's diversity can pose many problems for segmentation since traditional demographic or geographic segmentation may not provide a segment with significantly similar and useful traits or characteristics. To add to the challenge of diversity, the composition of the South African market is continuously changing (BFAP, 2009) as austerity measures to decrease the inequalities of the Apartheid past are implemented and urban migration increases. This makes it quite evident that the consumer challenges facing first world countries are remarkably different from those in developing countries; where retailers constantly need to adapt to the different and changing needs of their market and less to sophisticated, global, trend-following needs.

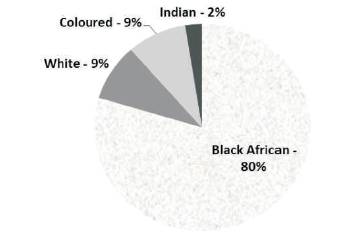

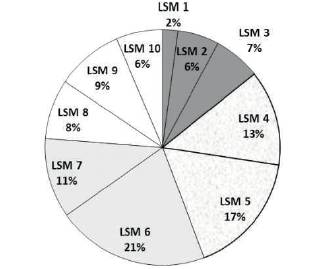

The South African Advertising Research Foundation (2012) has developed a method of segmentation (See Table 1) of the South African population which allows the identification of target markets relatively accurately. The Living Standards Measure (LSM) is based on access to amenities and services as well as geographic indicators as a measure of standard of living.

Table 1. Parameters derived from LSM segmentation

By this method of segmentation, the South African population is divided into 10 segments named LSM 1-10. The scale indicates LSM 1 to be those individuals with the lowest living standards in South Africa and LSM 10 having the highest. Characteristics (Table 1) were then determined for each segment based on demographics, media and general attributes.

Through LSM grouping, the largest proportion of the South African population fall in the LSM 1-5 segments. However, it is good to keep in mind that the segments with the most disposable income fall within the LSM 7-10 group and they make up more than a third of the South African population (SAARF, 2012).

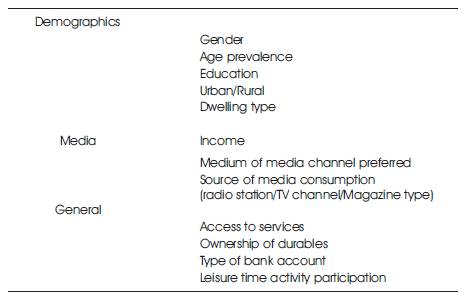

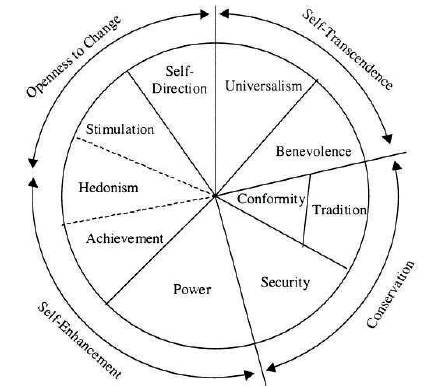

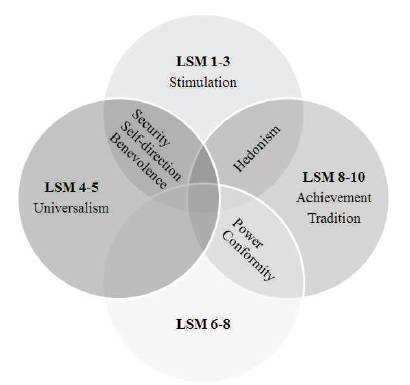

Schwartz (1994) extended his research and applied motivational goals to the values described in his earlier work. These motivators included Self-direction, Stimulation, Hedonism, Achievement, Power, Security, Conformity, Tradition, Benevolence and Universalism. These values were then organized according to motivational similarities which further enhanced the usefulness thereof. Thus, according to Figure 2 (Schwartz, 1994) it is seen that four dimensions arise indicating two societal conflicts between values. The first is the conflict which is the struggle between change (stimulation and self-direction values) versus the preference to preserve traditional behavior and stability (conformity, tradition and security). The second values’ conflict stems from caring for others’ well-being, and perceiving them as equals (universalism and benevolence values) versus a mind-set, which focuses on personal achievement and strive for positions of authority and wealth (achievement and power values).

Figure 2. Conflicts in Value Dimensions (Schwartz, 1994)

In a study conducted by Ungerer and Joubert(2011) , an integration of the Schwartz value dimensions and the LSM segmentation technique was devised. The LSM segments were divided into 'super groups' namely LSM 1-3, LSM 4-5, LSM 8-10 and LSM 6-7 (in descending order of segmented population size) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Population Distribution among LSM Segments

Statistically significant data determined the most important values to decision-makers in the respective segments. Interestingly, the entire South African population measured showed similar trends in the importance of certain values.

Values are also adapted to certain life circumstances so that those which are relatively easy to attain are given higher importance than those which seem to be 'out of reach'. This is evident in that LSM group 8-10 places are of greatest importance (more so than LSM 1-5) on power since it is perceived that those with greater wealth can pursue positions of authority much easier than, perhaps, those at lower income levels. Similarly, this group placed great weight on the achievement value. Following the same rationale, it makes sense that the research indicated that the values of benevolence and security were most important LSM 1-5 (Ungerer & Joubert, 2011).

Ungerer & Joubert (2011) derived statistically significant values for each of the LSM 'super groups'. LSM groups 6-7 and 8-10 place highest importance on both the power and conformity values, where LSM 8-10 additionally indicated greater emphasis on hedonism, achievement and tradition values. The benevolence, self-direction and security values were deemed as most important in the LSM groups 1-5 (See Figure 4). As mentioned earlier, these are evidently values considered attainable by these lower income individuals. The LSM segments 4-5 indicate significant importance on universalism versus the additional values of hedonism and stimulation of LSM segments 1-3. Figure 5 clearly illustrates the relationship between the different super groups. It can thus be deduced that when targeting LSM 8-10 based on value sets, automatically the target market includes LSM 6-7. This is particularly valuable information since this is the group which makes up the majority of the South African population and is constituted of the segments with the greatest income and, is also the most upward mobile division of the population (BFAP, 2009). According to the two conflict dimensions in Schwartz's circular model (Schwarz, 1994),the LSM segment 1-5 is ruled by 'openness to change' and 'self-transcendence' thus reflecting that decision makers in those respective groups are less individualistic and socially aware and place more importance on freedom. The LSM 6-10 segment can be described as being ruled by self-enhancement and conservation values. The results also align with the Swartz circular model where hedonism shows correlation with the progression from a population place predominantly in the top left section clock-wise, to a bottom left section where hedonism is a statistically significant value in LSM groups 1- 3 and 8-10. Thus, it can be deduced that the LSM segmentation technique is a relevant tool which can be used in conjunction with established 'gold standard' models of behavior.

Figure 4. Relation of LSM segments to the rest of the South African Population with regard to Schwartz's Values (Ungerer & Joubrt, 2011)

Figure 5. Characteristic and Shared Values of the four 'super groups'

For the remainder of the paper, the authors refer to the South African market as being composed of two large segments. Group one will be comprised of LSM 1-5 segments and Group two out of LSM 6-10 (see Figure 6). Understanding the key motivators and values of these two groups will help to improve the targeting process for marketing, and product position. Wang et. al (2008) showed that personal values and such other factors including income, indeed had an effect on the purchase habits of individuals.

Group one is governed by the openness to change/selftranscendence values. Karp (1996) identified that those societies are more often than not, 'pro-environmental' are keen activists who would call for social change which would benefit the environment. The Swartz motivators can also be applied to certain consumer behavior patterns. Wang et. al (2008) indicated that the security (2008) value may have an effect on the pattern of savings in these individuals thus they may be more careful and calculating in purchases. Self-direction is a value which will result in predominantly independent decision-making. This is especially valuable, since depending on industry, it can be useful to know how, and if decisions are, being influenced. Wang et al (2008) also found statistically significant results when assessing the stimulation value with the adoption of high-tech products. This is congruent with Schwartz's (1992) conclusion that the needs associated with this value and openness to change dimensions should be satisfied by novelty and excitement. Benevolence and universalism are two values which are associated with socially conscious purchases and are also indicators of frugal purchasing habits (Pepper, Jackson, & Uzzell, 2009).

Group two individuals have adopted the selfenhancement and conservation dimensions of Schwartz (1996). When it comes to environmental issues, these individuals are not necessarily pro-environmental, they will only act environmentally aware, and advocate the movement, if it is the norm. Further values which describe these individuals include achievement and conformity. People who are strong on achievement values place high importance on status and thus purchasing items which build up this image such as cars and cell phones, in the South African context (van der Merwe, 2005) and will be relatively popular. Power values usually go hand-in-hand in individualistic societies and add a dimension of wanting to choose and control an environment, as much as possible. Thus, appealing to this need to choose, and providing many options, may improve involvement of these consumers. Both power and achievement values are negatively associated with socially conscious buying, (Pepper, Jackson, & Uzzell, 2009) therefore, further confirming the individualistic nature of these individuals. Group two individuals also follow traditional values which affect their attitude towards existing products (Wang, Dou, & Zhou, 2008). Societies which follow traditional values will be more loyal to certain brands, thus for this segment fewer market innovations will be accepted. Conformity values indicate that this segment may appreciate personal advice from acquaintances and family and behave according to societal norms (Wang, Dou, & Zhou, 2008). This value has also been associated with frugal purchasing (Pepper, Jackson, & Uzzell, 2009) so, a conformity value society requires specific marketing and product positioning to effectively target this segment.

A number of trends have been identified for the South African market. Many of them are in line with global consumption trends with a few discrepancies.

With regard to LSM segmentation, there has been a significant migration of segments from lower LSM ratings to higher living standards. Over a period of seven years, all segment groups (LSM 4-5, 6-8 and 9-10) except LSM 1-3 have shown an increase in numbers ranging from 14%- 40% (Table 2). Another interesting trend is the increase in the Black African middle class(BFAP, 2009).

Table 2. Summary of Application of Schwartz Motivators and Trends on Consumer Behaviour of LSM Segments

South African food consumption is in line with global food trends. BFAP (Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy) has shown that the three most prominent trends (according to new products adopted) in this industry are indulgence, convenience and health with the focus on children and ethics trailing. It is interesting to note that the trend of convenience was rated much stronger than the global average and competes with health products for second place. A closer analysis of more specific trends indicate that the top three trends are (i) novel or interesting flavors, (ii) variety and (iii) presentation/packaging the fourth positioned is more or less shared between fun, natural, low fat/diet and fortification. Thus, it is evident that the first three trends describe the indulgence dominant trends and the last three mentioned are those pertaining to the dominant trends of health (BFAP, 2009).

Certain trends have been identified as applicable to the South African population (van der Merwe, 2005). Two strong trends for the South African middle class (LSM 6-8) were identified as the Body Beautiful Trend and the Staying up Trend.

The Body Beautiful Trend is fast growing in South Africa with the main motivator being the fear of obesity, acknowledging that image is everything. This relates to a lifestyle which is very image conscious and materialistic and which is very health conscious. The main target market in this segment would include the young emerging market. Most successful products would be those relating to gym memberships, health foods and lifestyle magazines (van der Merwe, 2005).

The Staying Up Trend is a new South African trend which appeals to materialistic and stylish lifestyles. Targeting the new emerging upper class, as mentioned earlier, with upmarket goods such as travel packages, houses, schools, cars and furniture would have the most appeal. This trend is borne out of the 'new' post-Apartheid South Africa where redistribution of jobs and freedom of movement is prevalent. Thus, this trend is especially appealing to the new elite in LSM 7-8 and new arrivals into LSM 6 (van der Merwe, 2005).

Although deciphering the South African population is a challenging task, applying traditional models for guidance and innovative new marketing techniques represent a key to understanding the present and predicting the future consumer behavior.

This paper has identified that the South African population can be segmented into four 'super groups' each with their own set of dominating values and motivators. By assessing these four groups, it is clearly evident that dividing the population according to living standards provides a useful tool for developing marketing strategies. The integration of LSM segments and Schwartz's value models has provided a platform upon which to pre-empt decision-making processes of groups and forecast trends within these clusters.

Understanding preferences and the influence of values on certain aspects of consumer behavior will make the South African market more attractive and viable for international investors and local entrepreneurs alike. Thus, further empirical research into the effect of Schwartz's values on decision making and application onto different industries is encouraged.