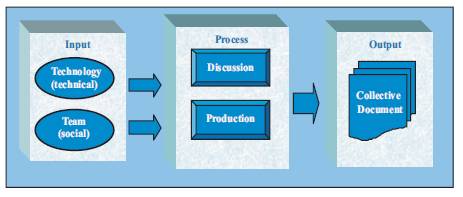

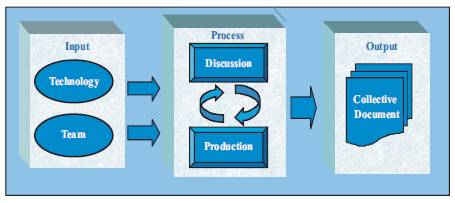

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Virtual Collaboration

The evolution of information technology that transcends time and space has enabled organizations to leverage virtual team collaboration. New collaborative technology, such as Google Apps/Google Docs, has disrupted traditional assumptions about collaboration. This empirical study on virtual teams examines how social and technical influences shape collaboration. It analyzes the performance and process of collaboration to detect changes, if any, brought about by modern collaboration tools, as well as the implications to organizations that deploy virtual teams. The findings show that new tools promote changes in the process of collaboration from a sequential to an iterative cycle of discussion and production. Practitioners can benefit from the insights of this study by evaluating the nature of teams and the support provided for their collaboration. In addition, collaborative technology has differential effects based on the social dynamics that occur within virtual teams.

The evolution of disruptive information technology that transcends time and space has enabled organizations to transition from in-person to virtual team collaboration (Frankforter and Christensen, 2005; Muthusamy et al., 2005; Strubler and York, 2007). Collaborative technology is an umbrella term that includes wikis, blogs, podcasts, chat platforms, video conferencing tools, and messaging/emailing applications (Purvanova, 2014). Some of the traditional challenges in deploying virtual teams include logistics (e.g. deciding on a common time) (Terzakis, 2011), infrastructure (e.g. setting up the means to access the technology), efficient facilitation of members' interaction to ensure equal contribution from all, and accurate scribing of the exchanges among members (Cramton, 2001). Most of these challenges have been mitigated, however, by current collaborative technology through functionality, such as availability (ability to access the technology from any location), asynchronicity (ability for different members to work at different times), electronic facilitation (built-in tools that moderate member interactions), and electronic memory (built-in memory artifact that keeps record of the interactions). Increasingly, organizations have utilized advanced technology to deploy virtual structures for organizational tasks (Kankahalli et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2004).

This study explores virtual team performance and creativity using modern collaborative technologies. It investigates the process of virtual collaboration and the progress brought about by the use of advanced collaborative technology. The study adopts a socio-technical approach in analyzing virtual team performance, creativity, and process by looking at the social composition of the team (focusing on how interactions occurred in the past among members) and the technical utilization of a technology artifact in collaboration.

Virtual collaboration can be conceptualized using an input-process-output model. The technology tool is an input that facilitates the process by which virtual teams collaborate in producing the output. The process of collaborative development includes the phases of discussion and production. In the discussion phase, members discuss and map out a frame for collaborative activity in terms of what to do, how to do it, and who does what. It is a stage in which members chart out or brainstorm the details of the activity and exchange tacit and useful information regarding the tasks at hand (Ghoshal et al. 1994, Hansen, 1999; Levin and Cross, 2004; Szulanski, 1996; Uzzi, 1996, 1997). In the production phase, team members integrate their different contributions and develop one holistic output. This is where the individual contributions of members merge to create a comprehensive output document.

Another input that plays a role in the process and outcome of virtual collaboration is the nature of the team itself. Existing teams, in which members have a history of working together, already have developed a set of ties and strategies for collaboration. These include self-reinforcing rules governing appropriate actions that enable the team to coordinate their activities successfully (Weber, 2006; Yoo and Alavi, 2001) and manage conflict effectively (Kankanhalli et al., 2006). On the other hand, members of newly created teams have yet to learn how best to work with each other. These group dynamics play important roles as input to the collaborative process (Yoo and Alavi, 2001).

Thus, the effectiveness of collaborative development rests on a combination of the social and technical aspects influencing how team members interact with one another when working toward a common goal (the team process) and how well they utilize technology to produce the final output, or document (the team performance) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Virtual Collaboration

The media-dependent aspect of collaboration focuses on the medium of communication (technology) as an important element in collaboration (Yoo and Alavi, 2001). The technology medium can influence and facilitate the collaborative process by offering such features as enhanced speed with which information is exchanged; multiplicity of information to be exchanged; the opportunity to fine tune information before it is exchanged with other members; and reprocessing information that already has been exchanged (Dennis and Valacich, 1999; Dennis et al., 2008). This study looks at the ability of the technology for reprocessability of information in two ways: allowing existing members to revisit prior messages for additional consideration before exchange (Dennis et al., 2008); and allowing late-joining members to get up to speed with past activities by following the communication thread Nunamaker et al., 1991). This capability of communications technology represents a sort of human memory in a group context and is also referred to as group remembering (Sarmiento and Stahl, 2008). There are very few empirical studies on memory in the performance or process of collaboration (Tyran and George, 2002). This study looks at the artifact in terms of memory provided by collaborative technology to facilitate reprocessability. It also addresses the role of memory artifact in the collaborative process and performance of virtual teams.

The social construction perspective of computer mediated collaboration focuses on the social or contextual factors in collaboration (Yoo and Alavi, 2001). This perspective rests on the idea of the team as an entity in the collaborative process. The nature of the team reflects the way in which the team functions and utilizes the technology for collaboration (Chidambaram, 1996; Carlson and Zmud, 1999; Walther, 1995). Teams with members who have worked together in the past may utilize the collaborative technology differently than teams in which members are new to each other. Teams with members who have worked together before are referred to as established teams. Teams with members who have never worked with each other and have no history of interactions are referred to as ad hoc teams. Team history presents differences in the manner of communication and exchange in collaboration. Research on types of teams has not been conclusive in terms of performance and/or creativity of teams (Watson et al., 1993; Jarvenpaa knoll, and Leidner, 1998; Maznevski and Chudoba, 2000). In this study, team history and lack thereof are used as social influences to aid the study of the collaborative performance and process in virtual teams.

In this study, Google Apps (with Google Docs/Google Chat) is the collaborative environment. Within this collaborative environment, the technical dimension is the technological memory artifact that is operationalized by the transcript feature Google Chat offers. The social dimension includes the composition of the teams in terms of history—established versus ad hoc teams.

The process of collaboration is operationalized by, first, a discussion phase, whereby members use Google Chat to discuss and exchange information, and, second, a production phase, whereby they use Google Docs to craft the final output. The output is the collaborative document that is produced by the team using Google Docs.

The objective of the study is to examine the role of novel collaborative technologies, such as Google Apps, on virtual teams in terms of performance (and creativity). By analyzing the role of technological memory artifact and the social dynamics in team composition, we evaluate the process of collaboration.

Specifically, the study addresses the following research questions:

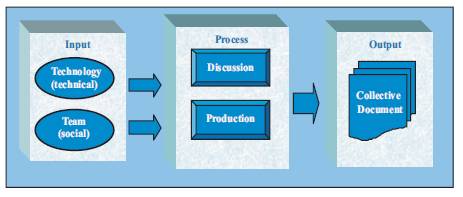

This study is devised to gain insight into virtual team collaboration using a 2 x 2 (with/without technological memory artifact; with/without team history) factorial experimental design. There are four levels of collaboration: two levels operationalized through the presence or absence of technological artifacts and two levels implemented through the composition of the team (established versus ad hoc). The four levels of the factorial design are: established teams with chat transcript, established teams without chat transcript, ad hoc teams with chat transcript, and ad hoc teams without chat transcript.

A total of 357 participants were recruited from the undergraduate student population of a large urban business school. These participants were organized into 19 three-member teams. About 60 teams were comprised of members who had worked together before—the established teams. The remaining 59 teams had members who had never worked together before—the ad hoc teams. For each member of a team, customized Google accounts were set up with the functionality that allows interaction among team members.

All teams were assigned the task of developing a collaborative report containing recommendations for a hypothetical university's new emergency management website. The report had to incorporate recommendations for both the design and the content of the website. The design component was assigned to elicit creativity in recommending features for a graphical user interface. As for content, the teams addressed the different phases in emergency management: emergency planning, emergency notification/alert, and emergency recovery. In the end, each team was to produce an output document that could be measurable both in terms of creativity and overall performance quality. While it is true that specific instructions were given on addressing the different phases of the emergency management function, there was no enforcement of any structure within each phase. Plus, the teams had the discretion to incorporate any material within each phase. In this way, teams could produce heterogeneous reports that allow for assessment of creativity. It is noted later in the discussion section of this paper how the modularity of the task (in addressing the different phases) had ramifications on the overall process and outcome of collaboration.

A synchronous virtual collaborative environment using Google Apps was created by having team members work at the same time from remote and dispersed locations that obviated the possibility of face-to-face interaction. The collaborative development was explicitly divided into the traditional phases of discussion and production. In the beginning of the experiment, the teams were allotted time to discuss the task using the Google chat interface (discussion phase). Google chat features the generation of a chat transcript that captures members' interactions. The transcript can be retrieved at any time. For the purpose of this study, the transcript was operationalized as the technological memory artifact, and members interacted using only the chat interface. At the end of the discussion phase, the teams were assigned time to collaboratively develop the report using Google Docs (production phase). During the production phase, access to the chat transcript generated during the discussion phase was given to 31 established teams and 29 ad hoc teams. The remaining teams (29 established and 30 ad hoc) were not given access; this was implemented by assigning freshly created Google accounts for these team members. This way, the new accounts would not have a transcript from prior discussions. The other teams continued to use the old accounts that contained chat transcripts generated in the discussion phase. The four conditions with the team distributions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Number of Three-member Virtual Teams per Condition

Team performance was assessed by analyzing the reports generated using Google Docs. Instead of self-reported measures of performance, as is done in most cases, this study used a panel of three external evaluators (blind to the experimental conditions) to rate the team reports in terms of creativity and overall quality. The evaluators provided scores on creativity using a 1-to-7 scale, and an overall quality assessment based on 100 points. The inter-rater reliability of the evaluators' scores for creativity was .84, and for overall assessment .89. The average of the evaluators' creativity ratings and the average of the evaluators' overall scores were used to assess a comprehensive measure for team performance.

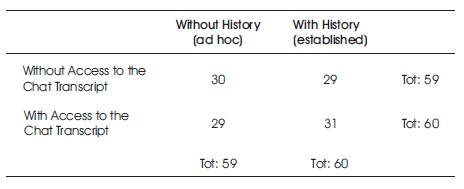

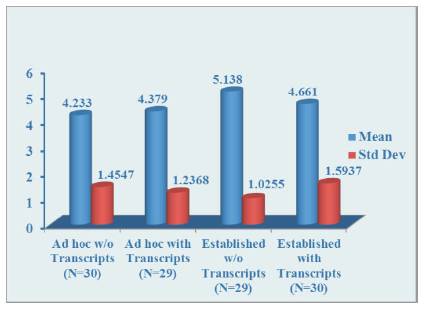

In evaluating performance, overall scores for the teams were very close regardless of their differences. The means are shown in Figure 2. The best performance was by ad hoc teams with no transcripts, followed by established teams with no transcripts, and then by established teams with transcripts. The poorest performance was by ad hoc teams with transcripts. In general, teams with no transcript access performed better.

Figure 2. Team Performance Results by Condition

Our expectation had been that teams with access to the transcript would outperform those without access and that teams with history would outperform those without. As it turned out, teams with no access performed better.

As an additional measure of performance, team creativity was assessed according to the ratings provided by the evaluators. The means for each condition are shown in Figure 3. In this case, the only significant model was a one-factor Analysis of Variance using History. The marginal means show that established teams outperformed ad hoc teams in terms of creativity (Means 4.3 vs. 4.9; F = 5.61; p-value =0.02). This revelation is both interesting and contrary to the traditional perception that ad hoc teams, by virtue of their low history of interaction, will be diverse and thereby more creative in introducing a variety of ideas.

Figure 3. Team Creativity Results by Condition

Interestingly, differing dynamics were observed for performance and creativity in each condition, which are elaborated below.

The ad hoc teams with no access to the transcript performed well, though not creatively. As constituents of newly formed teams, these ad hoc team members had no prior experience of working with their teammates. But the members made a concerted effort to overcome the absence of transcripts and the lack of history in crafting their reports. While they were able to collaborate effectively in terms of the output, they did not fare well in terms of creativity. This is counterintuitive because traditional work on virtual teams and group collaboration suggests that ad hoc teams, by virtue of having diversity and multiplicity of views, would tend to be more creative.

In addition, the absence of memory (transcript) is supposed to have facilitated unbound thinking or creativity, but this turned out not to be the case.

The members of ad hoc teams that had access to the transcript relied wholly on the content of their prior discussions to craft their report. The fact that they had no history of working together made them hesitant to interact and exchange information and caused them to rely on the transcript. Their ad hoc nature coupled with the complete reliance on the transcript reduced the effectiveness and creativity of the output.

The established teams who did not have access to their discussion transcripts due to the experimental condition displayed greater creativity. In this case, the absence of a transcript (memory) of prior discussions encouraged greater creativity and outside-the-box thinking. In terms of overall performance, history of prior interactions facilitated the integration and collaboration of ideas in developing the final report.

The study showed that established teams with access to discussion transcripts underutilized this access in crafting the final report. Since team members had worked together before, they moved directly to preparing the report without even looking at the transcript. This freewheeling may have allowed them to either refine or branch out from their prior discussion and formulate more creative solutions for the task at hand. Still, the underutilization of the transcript, while aiding creativity, did not enhance overall performance.

Looked at as a whole, our results show in terms of the process of collaboration, there is definitely a change brought about by modern tools. In terms of performance, when modern collaboration tools are utilized, we found that technological memory artifacts do not play as significant a role today as they might have in the past, and team composition continues to have differential effects in performance (and creativity) even with modern tools. In other words, while on the one hand, chat Looked at as a whole, our results show in terms of the process of collaboration, there is definitely a change brought about by modern tools. In terms of performance, when modern collaboration tools are utilized, we found that technological memory artifacts do not play as significant a role today as they might have in the past, and team composition continues to have differential effects in performance (and creativity) even with modern tools. In other words, while on the one hand, chat transcripts were overlooked by established teams as redundant, on the other, they are misused by ad hoc teams at the expense of efforts to build rapport and interaction among members. While transcripts as memory artifacts do not seem to play a critical role in terms of creativity, the history of interaction among members does. Established groups were able to leverage their knowledge of each other and their use of the technology to produce more creative solutions.

The study reinforces how new collaborative technology alters some of the traditional perceptions around virtual team collaboration. We see the developments in the role (or lack thereof) played by technological memory artifacts or team history in performance and creativity of virtual teams, and in the collaboration process.

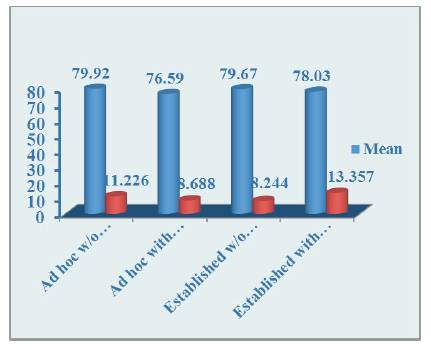

Our findings show a lack of significance of transcripts (memory artifacts) in the collaborative performance of teams. Unlike traditional technology that incorporated a sequential collaborative process of discussion and production, modern collaborative technology, such as Google Apps (Google Docs), allows the same workspace to be used at the same time for both discussion and production. This is evidenced in our study by how teams that were denied access to transcripts (memory) compensated by utilizing the Google docs interface to exchange ideas as they developed the final output in the production phase. These teams therefore customized the process to iterate between the phases of discussion and production. This is a reflection of not only the versatility of the technology, but also of the dexterity of the users in adapting the technology to fit their needs.

In addition, the nature of the task assigned to the teams influences the role of artifacts, such as memory, in team performance. Tasks involving interdependence among members require technological tools that differ from those that have modularity or no interdependence. For example, in the research task described here, the process of emergency management was defined in terms of the phases of planning, notification, and recovery. The members were able to work on the different phases without any co-dependence (e.g. having to wait for each other's input/output). In contrast, had teams been assigned a task that necessitated a linear sequence with an element of co-dependence (such as a programming task), there might have been differential results for the influence of memory artifacts. Practitioners should keep in mind the nature of the task when selecting and allocating collaborative technology and artifacts for virtual collaboration.

Traditional research on virtual collaboration posits that history of interaction between members in established teams adversely impacts the creativity of the team due to the natural tendency for members to seek concurrence (Janis, 1982; Sethi et al., 2002). Research also suggests that the lack of history among members in ad hoc teams necessitates a concerted effort by members to consider more options and perspectives, thus enhancing creativity (Ocker, 2005). However, this study shows how these paradigms are altered, with the introduction of modern collaboration technology. The study showed how ad hoc teams with access to the transcripts, as a memory artifact, focused solely on the artifact, without interacting and exchanging more information, thereby inhibiting creativity. In contrast, established teams relied on their rich legacy of interactions to continue the exchange and collaborate, uninhibited by the structure imposed by a transcript (memory artifact). These members recognized and acknowledged each other's expertise and diversity of ideas. Organizations should evaluate the assignment of a technological artifact for collaboration, but only after considering the nature of the team appropriating it.

The results of the study are bounded twofold, by the nature of the task assigned to the teams and the nature of the subjects who participated in the study. The task assigned in this study was one that allowed for exploration of team creativity. Other tasks may not produce the same result. In addition, drawing subjects from a student population allowed tapping into existing teams as well as creating new teams. The implementation of this design would have been difficult in other populations and settings. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that other types of tasks and subjects may produce different results. The results are also bounded by the nature of the collaborative technology-in this case Google Apps.

A direct implication of the results is that the process of collaborative development using technology has become more integrative. What was originally perceived as a sequential process of discussion and production has transitioned to an iterative discussion-and-production process (Figure 4). With this transition comes the acknowledgment that artifacts in collaborative technology need to be calibrated according to the social dynamics within virtual teams. Also important to recognize is the manner in which team members appropriate the artifacts in collaboration. With this study, the call was made to change the conceptualization of team collaboration from a sequential to an iterative process in which artifacts are freely used and incorporated in the cyclical discussion-and-production phase.

Figure 4. New Model of Virtual Collaboration

Practitioners can benefit from the insights of the study by evaluating the nature and the support provided for virtual teams. Organizations should evaluate the suitability of novel and free web-based tools in addition to the software support currently offered to virtual teams. With the evolution of social media and other means of communication, virtual collaboration will continue to evolve. The traditional facets of collaboration should be evaluated on a regular basis in light of new and yet-to-be created tools that will persist in disrupting the market.