Table 1. Modified Version of Feng and Karan's Topic/Theme Categories (Topacio, 2020)

Recent studies in gender representation tackle issues that no longer deal with the under representation, invisibility, powerlessness, and silence of women in the media. Hence, it is the aim of this study to analyze women's representation in a new light following the principles of feminism of difference. This study sought to prove that competing gender discourses and the notion of varying femininities are discursive practices that can be observed as strategies in representation in modern magazines. To prove this, multimodal analysis was used to analyze the verbal and non-verbal text of the magazine in question. Moreover, feminist critical analysis was applied to see how the use of diverse and competing discourses in the magazine are intertwined with the text producer's consumerist agenda. The analysis also shows how seemingly neutral or harmless discussions about feminine activities are actually embedded with biased ideologies on gender. A critical discourse analysis is deemed important in raising the awareness of readers regarding this manipulative process. It is through a critical look into language and discourse that one may find how unequal power relations do exist in social discourses.

Herman and Chomsky (2011) effectively illustrated how media uses its power to influence ideology through their propaganda model. This model explains that media's ultimate function is to serve the end of the dominant elite, or to propagandize the interests belonging to those financing them. Therefore, it is expected that the culture and ideology propagated by media works within a capitalist framework in which advertising and commercialism are important themes or goals. The domination of the elite and the powerful in media materialize through the operation of filters that allow them to show that the set of beliefs they propagate are natural and, therefore, unquestionable. While criticisms toward this operations by media have only been observed lately, the role of media in the manufacture of ideologies have been operating for some time. For instance, printed forms or publications like newspapers which seem to produce information in objective ways, but upon close analysis can reveal biases, and magazines which may create friendly dispositions with the readers through a set of helpful advice, but actually predisposes them to embrace consumerist ideas.

This shows how certain ideologies are effectively constructed amongst us, influencing our ways of thinking and behaving, in a way that we are not conscious of. The modes and ways of analyzing persuasion in discourse have taken a new trend. With the advent of new theories in discourse, including Critical Discourse Analysis, studies on persuasion do not only include effective persuasive techniques and strategies, but also the issue of power relations and the propagation of certain biased ideologies in the process of discourse ( Fairclough, 2013; Machin & Mayr, 2012).

Researchers in the field of gender in advertising have often debated on the significant role of media in the interpellation of ideas about gender and it seems that practitioners from advertising, and those coming from the field of socio-linguistics hold different points of view regarding the issue. Advertisers argue, in what is called the ‘Mirror’ point of view, that media advertisements only reflect realities and values already dominating in the society. On the other hand, sociologists using more critical frameworks claim that such realities and ideologies including gender are influenced and shaped by the media. In contrast to the ‘Mirror’ point of view, this so called ‘Mold’ point of view adheres more to the notion of gender ideologies as social constructs ( Grau & Zotos, 2016).

The magazine is considered one of the powerful tools in media by which gender ideologies are propagated ( Kuipers et al., 2017; McLoughlin, 2017; Talbot, 2013). Its glossy and colorful pages are filled with advertisements depicting men and women in certain styles and in specific roles while endorse the use of a particular product or brand. Studies on discourse analysis of magazines often discuss one or more of the following issues: representation of masculinity and femininity and that certain representations are more favored than others (Bradfield, 2019; Yuliang, 2010); the tendency of magazines to influence the formation of gender identities ( Del-Toso-Craviotto, 2006); with consumerism playing an important role in the creation and maintenance of certain representations ( Talbot, 2010), and the significant role of language in the construction of these gender identities ( Del-Toso-Craviotto, 2006; Talbot,2013).

Representations of femininity and masculinity is often a controversial topic in critical discourse analysis. As mentioned, advertisers have repeatedly claimed that representations are only reflections of social realities, and they do nothing more than reflecting men and women in their social roles. However, research in analysis of gender in media, which includes magazines, reveal several issues such as unequal representations between men and women ( Anderson et al. 2011), objectification of the female body in most cases where they are represented ( McLoughlin, 2013), and the favoring of certain standards of beauty; usually the 'white' and 'western' female over the others ( Brown & Knight, 2015; Johnston & Taylor, 2008). Unequal representation goes beyond a mere quantitative analysis of the number of appearances between men and women. Undeniably women have appeared more in magazines as they are the target of readers and consumers of advertisements. Rather unequal representations deal more with the kinds of roles men and women are often portrayed in, and this issue has a lot to do with gender stereo-typing. It has been observed that women are often observed in more traditional, less professional and 'decorative' roles, usually inferior to male roles ( Grau & Zotos, 2016). In a groundbreaking framework, Goffman (1979) semiotically described how women in advertisements are depicted inferior to men through analysis of certain factors such as body movements, positions in space, stereotyped activities, etc.

The issue of gender representation in media is deemed important and crucial in the creation of ideologies on gender and the building of gender identities among men, women and even children. It has been explained how the ‘mold’ point of view asserts that media is very influential in dictating how men and women should be like. For instance, the dominance of the white and western notions concerning beauty in magazines set a standard for even non-white women to attain. Nam et al. (2011) share their concern about how women may “unconsciously” accept these idealized concept of even when they are conscious of the fact that such a standard is hard to attain. Such conflicts may cause distorted identities, and result in societies where physical discrimination occurs.

Grau and Zotos (2016) maintains that gender stereotyping in media and advertisements is an issue that still prevails in many capitalist societies. However, it is important to point out that such categories in gender stereotyping should not also be taken in isolation and should not be seen as universally true for all men and women. Researches in critical discourse analysis are careful to note that socio-political situations in a particular society are different, and gender representations and issues in connection to them may vary from one society to another. Furthermore, one should be wary in claiming that only female representations are controversial and in need of our attention. Studies on masculine portrayal show how male representations also change over time ( Marshall et al., 2014; Temmerman & Van de Voorde, 2015). Lastly, Grau & Zotos (2016) also advises researchers to understand fully the discursive frameworks by which we see these issues. Hence, this present study does not only delve into a content analysis, but also espouses a semiotic analysis which according to Bell and Milic (2002) “has the advantage of enabling a richer analysis of texts by focusing on objective formal relationships.” (p. 203).

The objectification and sexualization of the female body is also prevalent in magazines. This issue is very controversial that Montiel (2014) highlighted the depiction of women’s nudity and commodification of women’s body in media including the magazines as the rise of many forms of sexual violence in the society. Along with this issue, some studies also claim that certain standards of beauty are more favored among others. For instance, McLoughlin (2013) has observed how the British magazine Asiana promulgates the ‘white’, ‘western’, and ‘wealthy’ standards of beauty. This observation is similar to that by Conradie (2013) as she found out how Indwe, an African in-flight magazine, tends to choose white models even in a country where the black race is dominant. In another study by Nam et al., (2011), it was observed how international and often “white” models still dominate Korean teenage girls’ fashion magazines. Although Korean models have become increasingly dominant, they observed a different style in their portrayal compared to the foreign models. Using Goffman’s classic framework, the study claims that Korean models are most often depicted as ‘childlike’ and ‘cute’, while the foreign girls hold a more sexual and independent image. In this article, the ways by which the female body is used and objectified in magazine images is also discussed. Although the objectification or sexualization is much subtler in the magazine in question, it was observed how a multi-modal and semiotic analysis can reveal that such issues are still present in modern magazines.

Grau and Zotos (2016) in their survey of gender stereotypes in advertising discuss how the advent of feminism and its influence and involvement in media issues paved the way to the changing representations of women in advertisements. Together with the changing economic roles of women in society, magazines are increasingly publishing more positive images of women compared to the traditional, stereo-typical and inferior roles in which we see them in the past. Some magazines are even keen on portraying the modern, empowered and independent woman. For instance, Pugsley (2007) described in a surprising and provocative cover of an issue of a Singaporean women's weekly supported by the line: ‘For women who want it all’, with the sensual image of a popular Chinese actress. To further assert his observation, Pugsley quoted Janice Winship’s positive counter claim on women’s portrayal: “the woman is ‘centre stage and powerful’ and that the gaze is not simply a sexual look between woman and man, it is the steady, self- contained, calm look of unruffled temper. She is the woman who can manage her emotions and her life. She is the woman whom ‘you’ as reader can trust as friend; she looks as one woman to another speaking about what women share: the intimate knowledge of being a woman” (1987, p. 12).

Studies such as this suggest that we are no longer just confronted with the under representation, invisibility, powerlessness and silence of women in the media. However, the new visibility and value of women in contemporary media does not signify that longstanding issues on gender representation and power are now less significant. Gallagher (2015) mentioned that issues about power, representation and identity remain at the core of discussions amidst developments in the local and global media, along with the emergence of new theories analyzing them. However, power relations in gender representations are no longer geared towards a discussion of women’s inequality with men: It can be observed from recent studies in gender and media that the concern about power has more to do now with how the more powerful use even the seemingly positive representation of women for achievement of their specific agenda.

According to Talbot (2010), magazines, like any other form of media, still exist to serve the interest of the ruling elite and the capitalist giants. She further argued that gender identities in modern industrial societies “are determined by capitalist social conditions and constructed in capitalist social relations.” (p. 138). Magazines, along with other ideological apparatuses, have played a significant role in the creation of gender ideologies in these societies ( Del-Toso Craviotto, 2006). Profitmaking is essentially what determines the production of magazines, and that its writers are not free to make several decisions regarding its production, but are controlled by “business methods”. This leads to the idea that discourse in magazine does not consist of neutral texts but imbued with ideologies that serve the consumerist agenda.

This may explain the diverse and often contradictory features of magazines, that is the use of multiple voices and genres (letters page, advice columns, recipes, advertisements, human interest stories, etc.) ( Talbot, 2010). The magazine has the tendency to develop the voice of a friend who seem to assist the readers in their real life dilemma and even present to them empowering ideas, but at the same time limits their world views to accommodate only the ideas supported by consumerism. The reader who thinks that she is reading fairly neutral and even friendly texts, not aware of the propagandizing techniques of the magazine to put her in a subject position to embrace certain ideas about femininity. Furthermore, Talbot argues that discourse practices of the magazine places woman in the role of the consumer, and that “this subject position is part of the femininity offered in women’s magazines, since feminizing practices involve the use of commodities.” (p.140).

It has been observed how studies on gender representations in magazines vary in their conclusions as to whether a conservative image or empowered image of the woman is propagated in this media form. While some magazines tend to fall back to traditional domesticated portrayal of women ( Rotman, 2006; Johnston & Swanson, 2003), other magazines are more aggressive in changing this image to a more powerful one. There seems to be the existence of competing discourses regarding the image of women in the magazine. It can be observed here that magazines do not only promote femininity as a singular notion, but rather as multiple or different femininities.

Coates (1998) defines femininity as an “abstract quality of being feminine” (p.295), and that femininity is something that is done, practiced or performed in order “to be” a woman. She further argued that we present our gendered selves in varying ways, in different contexts and performances. For some time, femininity has been regarded as a female characteristic that has something to do with “demureness, deference, and lack of power. ( Holmes & Schnurr, 2006). It is a term that can be associated with other stereotypical characteristics of women such as silence, passiveness, and even shallowness. It used to be a negative characteristic that it has always been regarded that to be feminine is to be shallow and absorbed only with insignificant matters such as beauty and fashion. However, feminists have recently salvaged the word to represent not only the “shallow” kind of femininity, but a term that represents varied ways of being a woman. Eckert and McConell (2003) mentioned that language and gender studies are now greatly considering differences and multiplicity of femininity among various cultures. In the tradition of “difference” feminist theory, feminist researches have abandoned the concern about male dominance, and focuses instead of a cultural approach to gender differences.

The emergence of varying femininities is especially possible in a modern world where the women occupy new roles in the masculine-dominated workplace, but at the same time expected to retain conservative values of femininity ( Coates, 1998). This resulted in varying ways by which women engage themselves in discourse. For instance, it must be noticed how women talk differently or talk about themselves differently as mothers, as wives, as career women or as individuals who play varied roles in the society. It cannot be denied that men are also instilled with characteristics of masculinity. They have their own share of expectations on how to perform their gender. However, changing social and material realities have placed a heavier burden on women who are expected to join labor production in a fast-paced industrial society while still being expected to perform domestic responsibilities within a traditional family.

Coates theory of competing discourses was applied in her analysis of women talk in oral conversations. This particular paper, argues a rather different notion of competing discourses as a discursive practice in femaleoriented magazines. The existence of varying femininities in the portrayal of women in magazines is a conscious choice of the magazine producers to address the present socio-economic conditions that prevail in today’s women’s lives. In theorizing this, Gallagher’s (2015) suggestions that gender studies in media should take into consideration the “socio-economic context of media structures” is taken into consideration (p.25). In this way, critical discourse analysis on gender not only focuses on representation of women’s lives that are biased and false, but also able to understand that the female representation is a product of the socio-political landscape in which it exists.

This research contributes to the existing and prevalent discussion of issues regarding gender, power and ideology in the society. However, instead of a repeated discussion of misrepresentations and unequal representations of the voiceless and powerless women in the media, this paper takes the challenge of discussing the issue of power relations in gender, using a framework that takes into consideration the socio-political and economic realities in which such texts are being produced. The paper considers a theory of difference rather than dominance. In other words, the representations of women in the magazines may vary because of differences in culture in societies and communities of practice. The differences may also be caused by the changing historical, economic and material realities women from different cultures find themselves in.

Furthermore, a definition of femininity that is not constant and universal, but a construct that changes according to history, social, political and economic situations is exposed to this study. Most studies in language and gender have delved into the issues of white western women. The theory of difference explains that the issues of the women of one class or race may not be the same faced by other women from other classes. Hence, this paper gives an opportunity to explore gender representations in the Philippines and how gender ideologies affect other social issues connected to gender.

Lastly, a feminist critical analysis of mass produced texts such as the magazine is significant to reveal how capitalists manipulate texts in order to promote gender ideologies that assist them in achieving their capitalist agenda. The paper intends to show how seemingly neutral or harmless discussions about feminine activities are actually embedded with biased ideologies about gender. A critical discourse analysis is deemed important in raising the awareness of readers regarding this manipulative process. It is through a critical look into language and discourse that one may find how unequal power relations do exist in social discourse.

This study sought to prove that competing gender discourses and the notion of varying femininities are discursive practices used by the magazine Good Housekeeping Philippines. Specifically, the research aims to answer the following questions.

Magazines texts are a combination both verbal and nonverbal symbols. In order to provide a description of its discursive practice, it is important to consider both the linguistic and graphic cues the texts are utilizing in order to create certain representations on gender. This particular paper primarily focuses on the analysis of images of women in the magazines, and also takes into consideration textual clues that support the interpretation of non-verbal ones.

The multi-modal analysis of the paper was guided by Kress’s multi-modal social semiotic framework. On the other hand, Mill’s feminist stylistics was the framework used to analyze how both textual and non-textual features of the text work together to create semiotic meanings that can be sources of gender ideologies.

In analyzing the verbal and non-verbal representations of women in the magazines, the social semiotic and multimodal framework based on the theory of Kress (2010) is used in this study. Coming from a post-structuralist stance, this framework argues that knowledge and meanings in the world are all socially constructed and susceptible to changes. The processes of representation and communication are responsible for the changes with regard to knowledge about the world. Representations, which give “material realization to meanings” (p.52), are constantly changing its resources, and, thereby also changing what is considered as “settled knowledge” in a society. Hence, it can be seen how representations are also socially created and motivated. On the other hand, communication is the process by which representations “are made available to others” (p. 49). As these representations are communicated, the social environment also gets reconstructed as it also changes the “potential of action” of the “participants in the process of communication” (p. 52).

The theory of Kress is multi-modal because it considers the meaning in all its forms. Signs in a communicative process is not only given through linguistic means but also largely through non-verbal cues which include graphic symbols such as pictures, colors and fonts in printed texts, and the supra-segmentals or paralinguistic strategies in oral ones. Apart from being multi-modal Kress’s theory is also social since it recognizes that meanings are not pre-given, universal or stable, but something that is created in a specific historical and social moment. In a social semiotic theory, signs are always made in social interactions and are motivated by the interest of the maker of the sign in a particular interaction. Hence, there is a non-arbitrary relationship between the chosen form or sign and its function in a specific discourse ( Kress, 2010).

The linguistic analysis of presuppositions discussed above aims to reveal the fact that these dominant linguistic features of the magazines are part of the informed decisions of the text producers. Furthermore, a multimodal analysis of the images in the text aims to support the idea that representation of women in magazines are motivated based on the interest of the magazine producer. Both verbal and non-verbal analyses are seen as important in arriving at a fuller description of the magazine’s discursive practices and the ways by which gender ideologies are created by such practices.

Feminist theories and studies in the French literary and linguistics scene have started questioning the role of language in propagating certain gender ideologies by combining psycho-analytic theories to language use. These theories have been highly instrumental in influencing other inquiries in language and gender studies, which according to McConnell-Ginet (1998) can be divided into two major categories: first, women’s language use as differentiated from men’s, and second, the ways women are represented in language.

This particular study focuses on the second category. Therefore, a feminist stylistics framework is very important to yield answers or results for the objectives set. Specifically, this study uses the feminist stylistics of Mills (1995; 1992). Here are reasons why the framework is deemed important: first, it allows for an analysis of language features of the text other than simply relying on content analysis to be able to extract ideologies present in a particular discourse; second, a stylistic analysis emphasizes on the foregrounding of certain features of the text that may seem natural or ordinary, but in reality provides an opportunity for more critical analysis of ideologies propagated by the more powerful entities in the society; and third, it aims to identify the socioeconomic factors that have led the language of the text to “appear” as it is, and the reasons that have made its interpretations possible.

The multi-modal analysis of both the verbal and nonverbal parts of the text support the first objective in doing feminist stylistics. After such analysis, this paper aims to foreground the discursive practices of the magazine such as the use of competing gender discourses and varying femininities as a way to promote consumerism. The discussion aims to reveal that a seemingly normal and ordinary language of the texts have hidden the meanings that can manipulate certain truths about gender roles in the society. Lastly, the study aims to consider the key role of socio-economic realities in which the magazines were produced to explain the function of the discursive practices based on Mills’ notion of Marxist-feminist stylistics ( Mills, 1992). This paper theorizes that the presence of competing gender discourses and varying femininities can be explained by the motivated interest of the magazine producers to also compete with the existing social, religious and moral values among consumers and the economic realities that contradict principles of consumerism.

This paper used a descriptive approach in determining the discursive practices of magazines, and how certain linguistic and non-linguistic forms are used to realize communicative functions. Hence, a qualitative approach was primarily used in the description of the verbal and non-verbal features of the text used in its meaning-making process. Qualitative method revealed whether or not magazines tend to favor more empowered images of the Filipino compared to more traditional or conventional ones.

The qualitative approach to research also served as a means of connecting language use to culture. Instead of relying purely on socio-linguistic variationist technique of counting the features of language in a text, the study also greatly took into consideration the socio-cultural factors that can explain why the texts appear as they are, and what is the connection of these appearances to their function in certain social contexts and communities of practice.

The sample included six (6) issues of Good Housekeeping Magazine Philippine edition published over a period of six months during the middle of the year 2017, namely March, June, July, August, September, and October. The selection was based on the recentness of the issues to effectively provide socio-cultural practices that are presently existing as revealed by the texts.

Good Housekeeping Philippines is a female-oriented magazine distributed by Summit Media. It is an offshoot of Good Housekeeping UK. According to their website, the aim of the magazine is to “help women save time, money and hassle thus allowing for more room, and encouraging them to pursue the things that make them happy and their lives fuller”. Its target readers are women between 35-55 years of age, married, have kids 1-15 years old, and belonging to B and C income levels. The magazine’s circulation in the Philippines is between 45,000 - 50,000 with an estimated readership of 225,000- 300,000.

The magazine was also chosen for its variety of contents that includes discourses on domestic and conventional topics like cooking, housekeeping, parenting, and at the same time also includes topics on economic and social responsibilities like money, career, mental and physical wellness, and advocacies. Because of these features and characteristics of the magazine, a wealth of competing discourses and varying femininities may be found and analyzed.

The procedure included a multi-modal analysis of the images of women in the magazines, and a critical discourse analysis of the images using the principles of CDA and feminist stylistics.

The first part of the analysis focused on the description of the images of women in the form of photos. All pictures that depict women are included in the data. In the analysis, it was identified to which text type the images belonged (i.e., advertisement, feature article, cover, title page etc. what roles do women seem to play in the pictures (i.e., mother, housewife, career woman, model, celebrity endorser, etc.), what topic was being discussed or what theme did the photo portray (i.e., cooking, beauty, fashion, health, money, career, social work, community service, travel, lifestyle, etc.), and how were the images portrayed in the photos (a description of what is seen in the photo itself and how was the photo structured by the text producer).

The multi-modal analysis intends to answer the research objective of describing the popular roles and images of the women in the magazine. Hence, it is important to identify in which roles are women typically ascribed, and whether or not a magazine published in the modern time still tends to depict women in the traditional roles or already in more modern ones. Identifying the themes of the pictures and the articles in which they came from was also important in describing the role the woman is seen to be depicted in the picture. Furthermore, using Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1999) visual grammar framework, the images were identified as to whether they depicted more of a reality or fantasy. Such analysis were able to reveal which images, roles and topics were usually given more realistic representation of the woman, and in which ones were projected in a more fantastical scale.

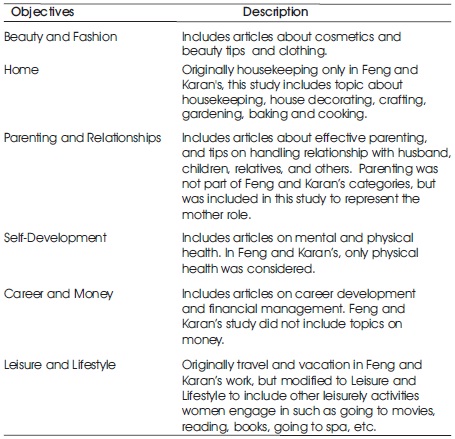

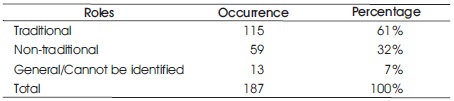

The magazine articles were categorized according to a modified topic category proposed by Feng and Karan (2011) in their study. This was done to establish whether the presuppositions and the content categories matched to portray an image of a woman who is either traditional/conventional or non-traditional/progressive. The articles in this research were categorized according to their content: Beauty and Fashion, Parenting and Relationships, and Home under traditional topics. Nontraditional topic categories include Career and Money, Self-Development (Mental & Physical Health), and Leisure and Lifestyle.

Table 1. Modified Version of Feng and Karan's Topic/Theme Categories (Topacio, 2020)

The following table shows a modified version of Feng and Karan’s topic categories.

The topic categories by Feng and Karan (2011) were modified to fit the themes offered by Good Housekeeping magazine and its target readers. Although used also for female-oriented magazines, the target readers were more of young and single women in China. In the present study, the magazine under analysis has target readers who are married and middle-aged Filipino women. Besides the topic categories were further classified by Feng and Karan as traditional and non-traditional. Traditional themes include fashion, beauty, family relation and housekeeping; non-traditional themes include career development, travel and vacation, social awareness, and human interest stories. The present study also sought to find out whether a traditional or non traditional theme is generally portrayed by the magazine in question.

Table 2. Modality Markers ( Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996)

The multi-modal analysis focused on the analysis of images in the magazines particularly the pictures of women. Guided by the social-semiotic approach of Kress (2010), a multi-modal approach aims to explain the different kinds of representations of women in the magazine. Generally, the paper aims to categorize the representation whether they adhere to a domestic image or a more modern, independent or corporate image of women. However, the study takes into consideration that there may be other images or more specific images that may appear or revealed after the analysis.

Language analysis to foreground features of the text is only the initial stage of feminist stylistics approach. After the multi-modal analysis, the paper aims to determine the instances of contradiction in the texts, in both verbal and non-verbal forms, to prove that competing gender discourses do exist as a discursive practice of the magazine. The analysis at this level also aims to determine the particular images or representations that contradict with each other. For instance, it is important to answer how the magazine strategize to promote the idea of femininity based on consumerism while also promoting an image of women who are smart and wise about money management. Furthermore, the paper discusses how the competing gender discourses and the use of varying femininities are ultimate tactics to promote consumerism among its readers.

Furthermore, if there are observed differences in presuppositions, representations and images, the paper tries to explain the relation of the representations to the socio-cultural background in which the magazine was produced.

One feature of critical discourse analysis is the ability to move beyond linguistic description and analyzing the instances of power relations in the discourse. CDA was used in this study to explain the role of magazine producers in the proliferation of certain gender ideologies in a society. The analysis in this level also included an explanation how competing gender discourses and varying femininities are used to promote feminist consumerism. Moreover, CDA examined how magazines are motivated by users of this particular discourse practice to achieve their capitalist agenda.

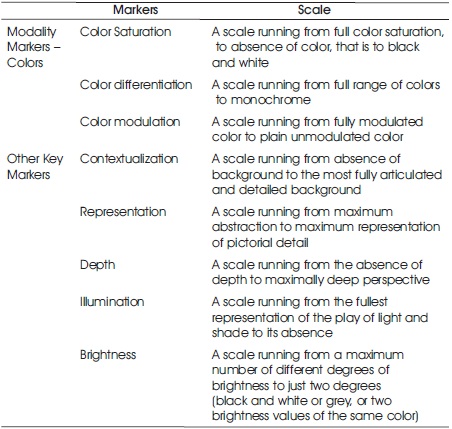

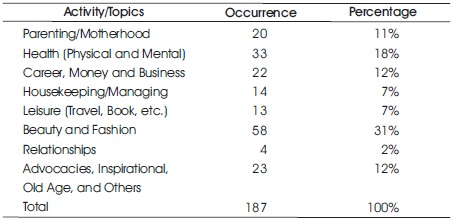

As expected, the images in the magazines are dominated by women in varying roles. There are instances where children are used in supportive roles, while men in the images are rare and, if they do appear, only remain in the background. There were a total of 187 images of women from six issues of Good Housekeeping Philippines analyzed in this study. Of the 187 images, 157 of them were taken from feature articles, 26 from product advertisements, and 4 from other sources such as the cover and the page. The images of women in magazines are represented in both advertisement and nonadvertisement text genres. The advertisements are observed to be usual print ads where the image part occupies the larger portion of the text, while the verbal information are few and only occupies a smaller space. Non-advertisements are usually full blown feature articles on particular topics which also use photographs to supplement the text. While images from advertisements are relatively lower in occurrence (13%) than those found in non-advertisements such as features articles, these images are larger and more vibrant in color in comparison to images from non-advertisement texts.

It was generally observed that women depicted in the images possessed physical and racial attributes of the Filipinos. There was also a tendency to make use of more Filipino women celebrities rather than western ones. The appearance of caucasian models were minimal in the issues analyzed. From this observation, it can be said that there was an effort from the magazine producer to localize the images, and elude from the popular practice of highlighting caucasian beauty in magazines.

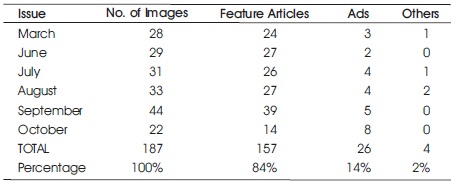

As for the roles, out of the 195 images, 115 tend to show women in their traditional and stereo-typical roles as mothers, homemakers and fashion conscious individuals, while 59 of the images depicted women in more “empowered” and non-traditional roles. The categorizing of women in traditional and non-traditional roles has also been addressed in other studies on gender and media. Feng and Karan (2011) mentioned that topics in magazines about beauty, fashion, parenting and housekeeping can be categorized as traditional, while topics on career, money, advocacies and selfdevelopment (mental and physical health) are nontraditional. These categories were based on analysis of previous practices in the earlier versions of magazines, especially those intended for housewives in western contexts. The images that were categorized as nontraditional are roles that are not considered stereo-typical or did not usually occur in magazines of earlier versions.

Table 3. Sources of Images within Magazines

It can be observed that while there was an effort from the magazine to “modernize” the image of housewives, the traditional image of women still occurred more frequently (61%) than the images of women in more non-traditional roles (32%). The traditional roles of women included those depicting women as housewives, celebrity endorsers of fashion and cosmetic products, fashion models, and party-goers/host. On the other hand, non-traditional roles are those that portray women as travelers, advocates, businesswomen, career women, fitness buff, artists, solo parents, etc.

Table 4. Roles of Women in the Images

The following table shows the activities of women depicted in the pictures and/or the topics of conversation in the articles in which the pictures are a part of.

Table 5. Roles of Women in the Images

Although the magazine is titled as Good Housekeeping, and originally intending to guide housewives in managing the household and purchasing reliable products that can help them in doing so, the newer versions included a variety of topics outside the original ones. According to the company’s website, the magazine was started in 1885 as a tool to guide housekeepers in creating better life within the household. When Phelps Publishing Company bought the company in 1900, its original intention was to “study the problems faced by the homemakers and develop up-to-date, firsthand information on solving them.” (“ The History of Good Housekeeping Seal, 2011). After a hundred years or so, the magazine found its way to other countries, and gave birth to local versions. Good Housekeeping Philippines is an offshoot of the magazine that originally targeted western middle-income housewives helping them in domestic matters. However, the local version was observed to have adopted topics beyond housekeeping and domestic affairs.

When it comes to portrayal of women in the images produced by magazines, only 7% of the activities or topics depict these women doing household/domestic chores. There is a proliferation of many other roles and activities women are seen to be doing. For instance, nonstereo- typical roles such as the career woman or the businesswoman (12%) and the health enthusiast (18%) have consistently been appearing in these magazines. Also, roles and activities that are least expected to appear in glossy magazines such as social advocates, artists, solo parents, travelers, and women who have hobbies originally associated with men are given space in the images and texts. However, it is interesting to note that the biggest percentage of roles or topics depicted in the images still have largely to do with a stereo-typical characteristic; that is 31% are related to topics such as fashion, beauty and cosmetics.

The different types of roles and images of women in the magazine show the varying kinds of femininities propagated by the magazine. Although the magazine originally targets house-makers, with its title Good Housekeeping, it recognizes that some of their readers in today’s society may be playing other roles. This discursive shift could be brought about by the changing social and economic landscape in which an increasing number of middle-class Filipinos are already taking both the roles as house-makers and career women.

The inclusion of other non-stereotypical roles such as social advocates or that of women with hobbies or careers usually associated with men (i.e., cars, backpack travelling, weight-lifting) reflects the magazine’s effort to widen the representation of women. At first thought, the portrayal of varying femininities rather than purely stereotypical representations may appear empowering, but a closer multi-modal analysis of the images would reveal that there are still certain biases as to the selection of which representations are given space in the pages of the magazines. For instance, the qualitative analysis shown above revealed that there is still a tendency to depict women more in stereo-typical roles. Second, there is also bias as to how certain topics, themes or roles are going to be represented. For example, it has been observed that images related to beauty and fashion are portrayed in larger, more colorful pictures, while images related to non-stereotypical roles such as advocates, career women and senior women are represented in smaller and unremarkable photos. The following visual and stylistic analysis of the images revealed more of this contradiction.

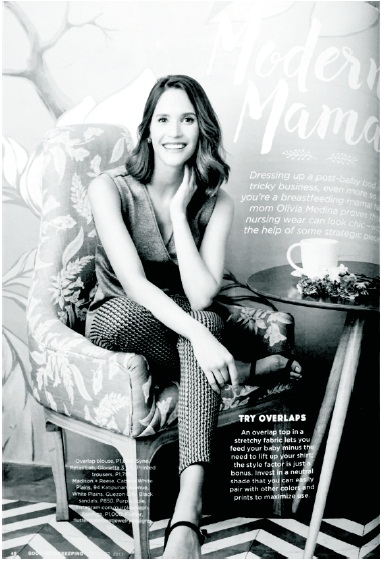

Women using cosmetic products or modeling latest fashion trends occupy a huge part (31%) of the magazine’s texts. Feature articles occur more than advertisements within the pages of the magazines, but several of the feature articles disguise themselves as a friendly guides to solve some problems. Within these feature articles, text producers insert mini advertisements in which they feature a product that can be a solution to a particular problem introduced at the beginning. For instance, Image 1 below shows the image of a model that occupies the same space with a title and introductory paragraph of the feature article.

Feature articles on fashion and even beauty are more visual rather than textual. Image 1 is seen to occupy more space than any other textual information on the page. The introductory statement’s job is to presuppose a problem for the reader. For instance, the example said, “Dressing up a post-baby body is tricky business, even more so if you’re breast feeding mama! New mom XXX proves that nursing wear can look chic – with the help of some strategic piece”. The challenge presupposed in the statement is the dilemma of finding appropriate clothes during post partum stage, where the mother is faced both with the pressure to breast feed around the clock and still looks good in the public. The presupposition in the statement includes both an assumption of the problem of the target reader and the expected ways by which such problems can be solved. In magazines, looking good and dressing up well are tantamount to exuding confidence that can lead a woman to achieve success in whatever she does. The model’s job in the picture is to show the confident-looking mother while wearing the fashion pieces being endorsed by the magazine. Below the image, information about the brands being worn (i.e. name of brand, price, store information) is written in small discreet letters. Feature articles such as this are structured in a way that they seem to appear as a friendly guide for women, but hidden within the structure of the article are subtle ways to advertise products that are key to solving the problems presupposed in the articles.

Women in images related to fashion and beauty occupy the larger and more amount of space in the magazines compared to images of women in other roles. As observed, although there was a move for the text producer to include non-stereotypical roles, the traditional image of the fashion and beauty enthusiast still dominated the pages of the magazine. This practice can be explained by Herman and Chomsky ’s (2011) propaganda model in which they explained that media firms are generally profit-oriented, and advertising is their primary source of income. Hence, it can be argued that there is a form of investment in placing well-curated, beaming and confident-looking Filipino women wearing fashionable clothes and expensive cosmetic brands rather than just showing these women in their ordinary appearance.

Figure 1. Photo from a Feature Article on Fashion and Motherhood. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, August 2017, p. 48.)

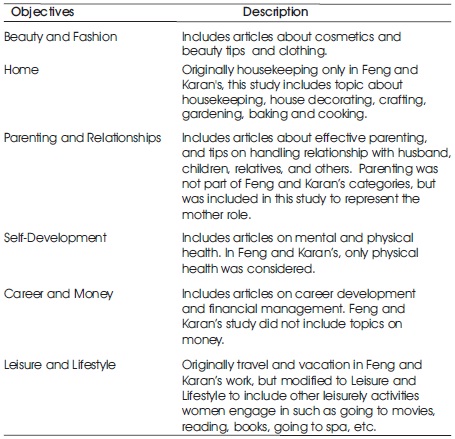

This paper argues that aside from unbalanced representations, the ways by which certain images are represented also contain hidden biases. Based on a theory of Visual Grammar, Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) argue that images can either indicate truth or fantasy, and the form by what the images are produced is already indicative of which is being represented. The truthfulness of photographs used in the magazines were analyzed using modality markers. Like linguistic modality, these markers also indicate the “truth value”, credibility, or potential of images to represent reality. A picture can have high or low modality, depending on the makers of modality such as color saturation, color differentiation, color modulation, contextualization, representation, depth illumination and brightness. A low modality is more distant to the truth compared to a pictures with higher modality, which are closer to the appearance of what is being represented in the real world.

Figure 2. Photo of a Mental Health Advocate. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, August 2017, p.88.)

Using this framework based on modality markers, it was observed that images of women in the magazines that are related to topics such as fashion, beauty, and at times Leisure, are represented in low modality. On the other hand, images of women related to topics such as health, money, career, social advocacies and other images of women in non-stereotypical roles are represented in high modality setting. Figure 3, for example, shows a woman showcasing fashion brands. The full body image of the model occupies a whole page in the magazine. She stands on what is essentially a devoid scene except for the bright hue of the background (peach-pink color) and some handmade cut-out clouds glued on the bright walls. There are two indications that this photograph is a representation of fantasy. First, the brighter and more saturated colors of the photos compared to lower saturation of photos representing women in other roles. Second, the scene is highly decontextualized. The absence of a realistic setting in this picture lowers its modality, hence, showing the woman as if in a “void”. The cut-out clouds (obviously not real clouds) heightens the portrayal of a dreamt-up world. The effect of such is that it shows the model as someone who is generic, which means not necessarily representing anyone in the real world. Hence, she is a fantastical representation of woman who might not really exist in any reality.

Figure 3. Photo of a Model in a Feature Article on Fashion. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, July 2017, p.47. )

In contrast, Figure 4 shows a woman using computer with her husband and daughter. The article in which the image appeared discusses what the readers can do in order to protect her family from online identity theft. The role of the woman in the image is some sort of the family’s guardian from technological hazards. It can be considered as one of the more “modern” and non-stereotypical roles that women can play at present. The photo occupies about ¼ of the page, a small space compared to the images related to fashion. The photo is produced with moderate modality setting which means the colors are not too bright nor soft; it introduces a context which is the living room, and uses a normal perspective that is not in any way too artistic. In other words, the image highly matches reality, and that the woman can be considered as a representation of other mothers and wives in the real world who take time and effort to educate her family members about technological pitfalls. However, it can be argued that the photo is in a way “real” and that the family (whether or not they are really related to each other) was just obviously asked by the magazine producer to pose for the purpose of curating the magazine’s pages. But then, the whole sense of categorizing photos as “fantasy” or “reality” does intend to exactly know which pictures captured and what really happened in real world or not, but more of an analysis of how the image producers chose to represent their message. A visual grammar analysis aims to know the techniques of producing images and also the purpose of communication.

Figure 4. Photo of a Woman With Family. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, July 2017, p. 82).

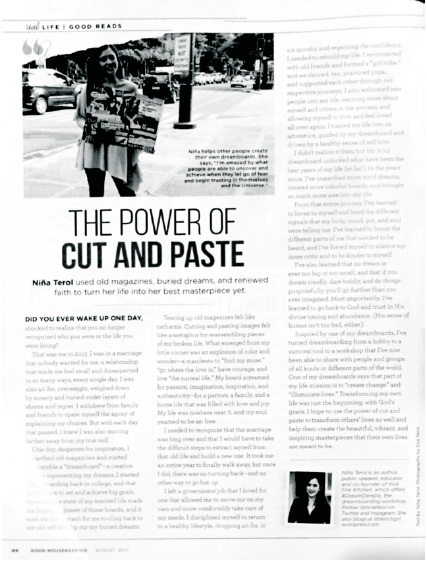

Some photos in the magazines are representation of real people in the real world. For instance, figure 5 is the photo of a woman who is also a subject of the inspirational article in which the photo comes with moderate color features, and is highly contextualized. Like figure 4. It also occupies a smaller portion of the page. In other words, this photo is not as attractive and eye-catching as figure 3.

Figure 5. Photo of a Writer in a Feature Article. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, July 2017, p. 84.)

In can be construed from this analysis that images in relation to topics such as beauty, fashion and leisure have a tendency to be categorized as fantastical representations because of their low modality. The fantastical representation of a woman can lead to an impression of a generic participant – the woman can even be a commoner. Such representations produced in photos of bright hues and artistic fashion does not only intend to catch attention, although this also is a highly possible motive for an article that inserts mini advertisements. A woman who is a product of fantasy can be a commoner but can also be an image that anyone can aspire to achieve. She is the representation of an ideal woman presupposed by the text producer, someone smart, confident and beautiful, and that this image can be achieved if the reader purchases whatever product is being endorsed in the mini advertisements that goes with the image. Hence, it can be said, as Kress and van Leeuwen argued, that the choice of modality markers are highly motivated signs. The text producer’s choices of which to represent and how such images are to be represented always come with a particular agenda. In the case of the images of women in magazines, much of their choices have to do with consumerism.

The use of metaphors are also discursive practices often used in the images of women in the magazines, and at times can also be a source of contradiction within multimodal discourse. In her work about feminist stylistics, Mills (1996) acknowledges metaphors as very influential in the ways we think about “certain scenarios in particularly stereotyped ways” (p. 137). Using Lakoff and Johnson’s model (Lakoff, 2006; Lakoff & Johnson, 1988) of conceptual metaphors, she discussed how men and women are given stereotypical attributes that usually manifest in metaphorical expressions at the sentence level. This paper argues that such metaphors also appeared in images.

Conceptual metaphors used in the images may be nonconventional, with artistic ways to convey a particular message ( Lakoff & Johnson, 1988). For instance, Figure 6 shows an image focusing on an electric plug with a woman in the background. The woman is fragmented and only part of the chest, hands and chin are shown in the picture. The fragmented body diverts the attention to the plug that the woman is holding. Metaphorically, the plug can represent the woman herself who is in need of disconnecting herself from something else. The particular article presupposes a woman who depends a lot on social media and online gadgets, that there is a need for her to consider connecting with real people. Hence, the plug is a representation of the woman who needs to unplug from the online world. The topic or image presented in this picture is non-stereotypical. The inclusion of the woman as gadget and technology savvy is a modern attribute that has its own share of challenges.

Figure 6. Fragmented Photo of a Woman in a Feature Article. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, April 2017, p. p.31.)

However, there are metaphorical representations that are still stereo-typical, and they usually appear in advertisements. Figure 7 shows an advertisement that uses such stereotypical metaphors. In this image, a cosmetic print ad shows the confident looking face of a woman embracing a man in the background. The photo focuses on the woman’s well-curated and made-up face, while the man’s face is fragmented. The cosmetic product being advertised is that of a liquid foundation, and the ad slogan at the bottom of the image says “Choose lasting, choose love”. Using linguistic analysis alone, it can be interpreted that the “lasting” characteristic is attributed to the cosmetic product that can last for hours on the user’s face. The product is being likened to “love” in metaphorical ways, which can also be “lasting”. When the ad said to “choose love”, it really meant to choose purchasing this particular cosmetic brand. However, an analysis of the image that goes with the text will give an impression that the idea of love is extended to the relationship of the woman and the man. It is important to note that the cosmetic product is represented as a catalyst that binds the man and the woman in the relationship. This example shows a form of competing discourse: that while the woman is being given the power to “choose” and take certain decisions about her money (the power to earn money and buy something with it), this power has been limited by a very consumerist framework which tells the woman that she has to purchase something in order to make his life satisfying.

It is also interesting to note that, although the woman is foregrounded in most images while the man is almost absent, some of the images of women are depicted in relation to men. Image 7, for instance, uses a metaphor that does not directly represent the woman like in Image 6, but it represents metaphorically women’s relationship with men, and that is, she has to be the one to exert extra effort (in a very consumerist activity) to make her relationship with him work.

Figure 7. Photo of a Model in a Cosmetic Advertisement. (Good Housekeeping Philippines, April 2017, p.45.)

According to Yule (1996), a presupposition is “something that the speaker assumes to be the case prior to making an utterance” (p. 25). Mills (1995) also argued that there are already certain presuppositions about the gender formed by text producers when they intend to address women as target readers. For instance, Mills further demonstrated how advertisements for female audience consistently presuppose that the woman reader has a problem she is facing. The presuppositions analyzed in the images in this study also revealed that presupposed meanings are present and that they give ideas about a the kinds of readers magazines are dealing with. Presuppositions derived from the analysis of images were able to provide the following image of the woman: 1) that the reader is a woman who is maintaining a career and a homemaker at the same time, 2) that the reader has husband and children whose well-being is her obligation, 3) that the reader maintains the traditional image of the woman who is domestic, in charge of managing the home, and doing home-related chores 4) that the reader maintains the traditional image of the woman who engages in stereotypical activities like shopping, dressing-up, hosting parties and going out with friends, 5) that the reader, although a housewife who does traditional roles, is also modern and keeping up with the latest fashion trends, gadgets and even activities, and makes independent decisions on money and finances 6) that the reader tries to adopt modern non-traditional attributes like being smart and confident, maintaining positive outlook in life, taking care of one’s own mental, emotional and physical wellbeing.

This contradictory nature of female-oriented magazines has also been observed by Talbot (2010) when she emphasized that “magazines are diverse and often contain contradictory elements” (p. 144). There seems to be an amalgamation of different voices in the magazines since it contains different genres and even diverse kinds of discourses. Although it can be said that this could be the effect of different authorship (unlike a book with only a single author), the diverse voices can also be considered as a strategy for the magazine to accommodate modern images of women without fully rejecting the traditional one. The reason for this is to offer the idea of consumerism as acceptable, without negating previously established values in the society.

This observation of contradictory images can also be related to Coates’ (1998) notion of competing discourses. According to this notion, women are able to perform varying ‘selves’ because they have access to varied kinds of discourses as well. Magazines as ideological apparatuses, through its different discourses, can create different ideas and images for women and provide possible roles that they can play interdependently. Hence, it can be said based on the analysis of presuppositions in this study that magazines uphold neither a traditional nor a non-traditional image of woman. On the contrary, discursive practices of magazines reveal that both images are upheld, and that competing discourses are used.

Competing gender discourses as discursive practice within magazines are realized in varied ways as revealed by multi-modal analysis and feminist stylistic analysis of images. One manifestation of such can also be observed in the competing kinds of images propagated by the magazine such as the stereotypical images and nonstereotypical ones. Women are seen in varied roles, some depicting them in traditional ones such as housekeepers, wives, mothers, fashion enthusiasts and party-hosts, and some in non-traditional ones such as health buffs, career women, social advocates, and other roles usually attributed to men. There is already an agglomeration of activities that women can be seen represented in, and there are even times when one image shows a woman in multiple roles. An example of this is the image of a mother who models fashionable clothes while breast feeding her infant in a public space. Second, there seems to be certain nuances in ways by which certain roles or activities are being represented. Images of fashionable women seem to be given more prestige than women in other ordinary or non-stereotypical roles as observed in the amount of spaces they are given in the magazines and the way the images were produced in terms of color and perspective. Third, there seems to be a competing discourse as to what ideologies are actually represented by the magazine.

Aside from the general competing images of the domestic versus the career women, more subtle kinds of competing representations are present. One example is the effort of the magazine to infuse socially-relevant discussion of women’s issues like body shaming. An article in the magazine features a pluz-size model’s struggle and her journey towards being body-positive. This effort is empowering many women whose body image does not conform to body images usually printed in magazines. However, it is to be noted that the instances where this rare “empowering” portrayal are shown are overpowered by the more significant number of images of slim, provocative, and sexy-looking women all over the magazine. In spite of the fact that the target readers are middle-aged mothers, the magazine stills has the tendency to favor, usually in advertisements, the younger and fashion model types of women. Ordinary-looking women with no frills and without high-end fashion brands are usually seen in non-advertisement feature articles. It is also noteworthy that aside from these images being kept in minimum, these photos are smaller, less vibrant, and less appealing compared to the bigger and colorful photographs of the advertisements.

Another instance of competing discourse is observed when the magazines infuse a rather “empowering” idea in traditional discourses about fashion, parenting and housekeeping. It is a discursive practice of the magazine to combine traditional ideas of femininity with nontraditional ones; that is why, an absolute categorizing of stereotypical and non-stereotypical magazine discourse may not already exist. A magazine discourse is characterized by many contradictions happening within it. For instance, there is a tendency for the magazine to infuse the idea of “investment” to shopping discourse. This allows such subject to lose its association with “shallow” femininity. For example, an article on fashion can show tips on how a woman can use the same black dress for different occasions by just mixing and matching accessories. This seems to be a smart tip that allows women to save. Hence, the presupposition that the reader has the tendency to splurge comes into the picture. The article presupposes a woman who is expected to save but still wants to look good. Hence, the magazine poses to be a smart friend that teaches the reader to be smart with money, but what is contradictory here are the other accessories they sell that should come with the black dress in order for it to look different. The same article provides a pair of shoes with the price and the name of the store from which it can be bought.

At first glance, it seems that the inclusion of nonstereotypical roles and topics is a way for the magazine to “modernize” and “empower” the Filipino women. In a country where there still exists a largely conservative culture but at the same time infused with western notions of beauty and femininity, it is empowering to see a diverse set of images of the Filipino women fulfilling various roles. In the images, women are given the power to choose and decide on matters about money, family, relationships, and self-improvement. However, each decision is also coupled with the expectation to purchase something. The text producers also have the good intention to feature varied racial features, especially that of the Filipino women. However, western standards of beauty are still given the highlight in the representations. Moreover, there are still several articles and advertisements, which emphasize the notion of “white” beauty in order to promote skin-lightening products.

In a deconstructive way, it can be said that rather than pursuing women empowerment, the use of competing ideas is observed to be a discursive strategy of the magazine to retain its consumerist agenda while downplaying negative associations with the traditional “shallow” definition of femininity. In highlighting the idea of investing rather than spending, the magazine producer also finds a way to overpower existing ideologies in the society that may contradict the goals of consumerism. For instance, spending and splurging in the Philippine society is not as acceptable as an idea compared to western ways of spending money. With the given social and economic background in which poverty is a reality, it is considered wise for Filipino house-makers to save rather than splurge. It is important to note that the magazine’s target readers are not single women, but middle-aged Filipino women who have their family as their responsibility. To this Filipino reader, any expenditure outside the family budget can be a source of guilt. By promoting certain expenditures as “investment” or a “gift” that they deserve for their hard work, the purchasing guilt is being lessened. In some other instances, like what has been discussed about Figure 7, magazine discourse also tends to show that the purchases women make are essential to building a good relationship with her husband, children, relatives and friends. The meaning projected here is that the effective ways of being feminine is largely based on what one purchases and how she can use it for her welfare and her loved ones as well.

There are several other instances of contradiction of discourses in the six issues of a female-oriented magazine. The analysis only proves to some extent that competing gender discourses and varying femininities are discursive practices the magazine producers use to attain consumerist agenda. First, varying images about being a woman are used to cater to different types of readers or different kinds of women within their target group area which comprises of the middle-class Filipino. The images are used to match the current realities, roles and issues of this group of women. Within discourses about femininity, the text producers infuse discourses about consumerism. Contradiction is observed to exist in three layers of discourse: first, there is a competing discourse as to the kind of image that represent the middle-class Filipino women on whether retaining the traditional image or highlighting the empowering or modern ones; second, there is contradiction and bias in the ways by which certain images should be represented in photos; and third, there is contradiction in the kind of gender ideologies propagated by the magazine.

Yet, competing discourses and the use of varying femininities seem to work well rather than hamper the goal of the magazine producer. According to Talbot (2010), profit making still determines the production of the magazine. The people who write for magazines are hardly free agents, and that they are only controlled by business methods. This is hardly surprising since advertising is a big source of income also for magazine publishers. The magazine firms can only do what corporation giants asks them to do regarding selling their products and services. To do this, magazine publishers and writers face another challenge: how do they present the idea of consumerism as an acceptable thing in the present society? Consumerism is a hard idea to sell in a society where economic instability is a reality, and social and moral values against consumerism are present. Hence, competing gender discourses is also a means to compete with the existing social, religious and moral values among consumers and the economic realities that contradict principles of consumerism. The magazine producer’s strategy is to retain certain traditional images, which support Filipino's social values like thriftiness, smart budgeting, charity, family-orientedness and even spirituality, but also slowly infusing ideas of consumerism within the discourse. This competition is done in very subtle ways playing with ideologies so that what is not acceptable in the present social framework may become acceptable without question.

The magazine text producer occupies a more powerful position in the discourse which recognized the material realities of its present readers. With this recognition, they are able to adapt their discourse to realities of the present times to retain its consumerist purpose. They continue to create myths on what women in society are like and supposed to be like, and present them as “truth”, when in fact they are biased and questionable. This paper reveals its agenda by using linguistic and feminist frameworks that exposes the rhetorical strategies of persuasion and manipulation employed by such consumerist texts.