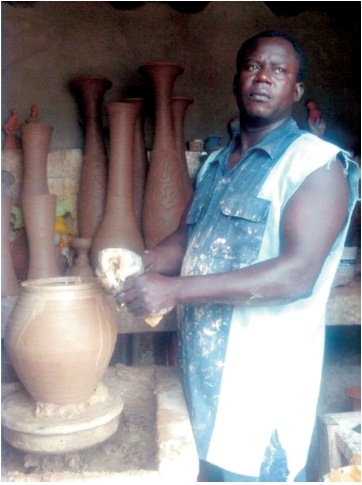

Figure 1. Ceramics Products Formed Using Local Methods, the Coil

This paper studies the technical processes, instruction and production techniques of pottery practices in the south west of Nigeria. It examined how indigenous technologies, norms and values in traditional pottery of South West Nigeria have evolved in giving continuity and socio-cultural experiences to the people, which they, in turn, can reproduce. The starting ground is that the dynamics in the manufacture of pottery itself would show the forms of contemporary technology, cultural, socio-economic, and knowledge relations in South-West Nigeria in particular. This paper has therefore directed us to try to report on technological knowledge inclinations and the social and cultural history of South Western Nigeria and the impact of modern technology.

In the long human evolutionary course “technology” is initially limited only to the forming and shaping of existing natural materials. In human history, amongst all the technological revolution that took place in the last 9000 years in the south-western part of Nigeria, ceramic production is one that has survived till date. Today there are many indigenous and modern pottery centres in South-West Nigeria. Ibadan, Iseyin, Fiditi, Saki, Ilora, Ogbomoso and Aawe in Oyo state, Ile Ife and Ipetumodu in Osun state, Abeokuta and Egbado in Ogun state, Igbara Odo andIjero Ekiti in Ekiti state, Erusu Akoko and Isua Akoko in Ondo state are some among them (Fajuyigbe & Umoru-Oke, 2005; Kalilu et al., 2006). Adeyeye (1979), commenting on African technology, reported that technological development in Africa was undergoing a process characterized by order and planning before it was abruptly interrupted by the Europeans. The th interruption started in the 5 century, first being the Arabs, which was followed by the Atlantic slave trade. Afterward colonialism came with total disorder, victimization and exploitation of Africa. People's ways of life were rendered unwholesome (Oyebola, 1982). Rather than promoting African indigenous technologies the technology and culture of the Europeans were imposed.

The effect of foreign technologies, art and market place practice, along with world-wide education, has had major outpouring effect on the social structure among the people in the south west of Nigeria. Pottery techniques in South West Nigeria have proven to be the most important concept for addressing the issue of cultural boundaries among the people. Pottery technologies in South Western Nigeria like elsewhere in Africa seem to belong to the larger low-technology domain that dominate most communities.

The potters in South Western Nigeria in particular and Nigeria in general offer a ground for a host of new technologies and innovations to researchers, investors and promoters of pottery and ceramics. In analysing the degree and extent of potter y practices and technological evolution in South Western Nigeria, it is however pertinent to understand how ancient pottery and ceramic technology has developed with the advanced use of scientific analysis and techniques. It began with the potters' attempt to produce desired colours and decoration for the clay-body and ended with native handling of materials, kiln temperatures and ambience to produce the high technology glazed wares. Although, formal education and new technologies have continued to shape the direction and nature of indigenous ceramics and pottery production in the South West of Nigeria, while changes in Nigeria's socio-cultural spheres have happened during the twentieth century. Local pottery production and technology largely remain hidden from the educational institutions that are themselves the products of the same historic and sociocultural inceptions. Thus, pottery can function as a positive-intellectual action at the native level and a communicative action at the technological level.

The introduction of modern pottery techniques and technologies into Nigeria's formal education system took an absolute turnaround of intentions in the manufacture and function of pottery. The introduction of modern pottery equipment like potter's wheels, kilns, ball mills and extruders subvert the local methods that were meant to satisfy local demands. The influence of western ceramics production and technology in Nigeria had revealed that formal education is the main basis for upholding cultural re-production (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990), and that there is a link between the kind of educational background of pottery end users and the levels of production and use of pottery, thus, showing the tie among technology, education, pottery production and its use in the region. Basically, the study was to discover the traditional pottery function with specific link to Nigerian pottery society, within the context of its making, alongside the complex symbolic, technological and ideological identity.

Figure 1. Ceramics Products Formed Using Local Methods, the Coil

The throwing wheel was the most wanted equipment by the most educated potters (Figure 2). There are locally fabricated throwing wheel mostly employing the modern technologies.

Figure 2. Ceramics Forms Using Mechanical Method, the Throwing Wheel

Ball mills (Figure 3) reduce wastages and gives fine clay desirable by most educated potters. However, traditional potters seldom use this method since they work on the clay direct from the deposits in wet form.

Figure 3. Ball Mill

Pug mills are used for big ceramic industry where a lot of clay materials are required. The ones available in South West Nigeria are manual and locally fabricated (Figure 4). The alternative to pug milling clay is using manual labour. Not only does the equipment dictate what potters' produce but it also determines the ultimate use of the products.

Figure 4. Pug Milling Using Mechanical Methods

An evaluation of Nigeria's educational pattern indicates that there are tendencies towards handling issues of intervention. Nigeria has either pursued a policy of technology integration by emphasizing the promotion of traditional pottery structures, undermining the local practices, or merely allowed events to take their natural course, usually in a restricted environment. Whatever line it has taken, it has had consequences beyond the scope of the indigenous communities, and has eventually dictated the technological directions of the state.

Nigeria's educational policy makers are fully aware of the linkages that exist among educational aspirations, social class structure, technological and cultural developments and thus, acknowledged the technological evolution in the region at an early stage. However, various tertiary institutions in the south west had shown tremendous progress in deploying qualified graduate trainees in the pottery and ceramic industry.

Kilns for firing ceramics is one of the main challenges of the Nigerian potters. In this part of the world kiln construction is still the preserve of a few technical experts. The most common design is one that uses straw, fire wood or gas as fuel. The traditional bon-fire technology readily comes to mind (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Stacked Pots Covered with Light Wood for Bon-Fire

Several ceramic studies have been carried out in South West Nigeria and neighbouring areas, (e.g. Ajekigbe, 1998; Akinade, 1995; Aleru, 2001; Anifowose, 1984). These researches had focused on sources and preparation of clay, ware forms, ware type, decoration, firing techniques, and marketing. For example, Ilora potters in modern Oyo State of Nigeria, classify clay into the following types: a mo-dudu (black clay), amopupa (reddish clay), amo-ewuyan (used as a temper), and amo-fun fun (white clay) (Ajekigbe, 1998). Fatunsin (1992) reported that there are two distinct types of clay in Saki, Okeho in Oyo State is the white and red; while at Imope in Ogun State, the white, red and black mixtures are the commonly used (Fatunsin, 1992).

In Yorubal and south west of Nigeria, local users of pottery vessels make purchase at the production centres while potters in distant villages carry vessels on their heads to sell at local markets which are within walking distance of the production centre (Fatunsin, 1992). In recent times, vehicles are arranged by potters through combined resources to transport wares to non-local markets. In most of the markets in the south west today, larger pot vessels are uncommon; what is unremarkably common are small vessels such as is asun, oru, amu, kutupu and konjo that are sometimes in demand for domestic and traditional ritual purposes.

Figure 6. Setup of a Locally Made Kerosene Kiln

It is no longer that hand built technique is the sole method of producing indigenous wares in Yoruba land; thus is the method practiced by the potters in South West Nigeria, its end product is often achieved through mould, coil and pinch, or the combination of the three.

Certainly, pottery has many similarities among the numerous societies who practise it. Independently, every society engaged in pottery has a unique approach perhaps influenced by its cultural norms. Even so, it will be needless to assert that a particular process or method is a preserve of any society. Overlooking any practice will also defeat the ideals of indigenous pottery and also the subject in question. Since literature on south western Nigeria pottery is insufficient, this sub-topic will draw from related concepts in a number of pottery traditions within the region under focus. These include clay digging and preparation and pottery in general, moulding pots, finishing and decorating pots, drying and firing pots and its uses in particular.

Figure 7. Mixed Mined Sieved Clay in the Open

Indigenous pottery is simple, functional and hand-built. The first thing to look for is clay. Clay, the main material, has a wide variation of properties used by the potters, and this often produces vessels that are unique in pattern in each locality.

Figure 8. Wedged Clay Left Age for Days Before Use

Female potters may insist digging their own clay because of their dependence on and affection to pottery activities, besides the domestic roles of pots. Traditionally, looking for and preparing clay predominantly goes with certain practices. In accordance with this conception, the spiritual value of traditional art requires certain rituals when preparing the base materials with which the artists work. The spirits that reside in such materials must be pacified. This practice goes with offering prayers and libations to safeguard the artist and the finished item. So the potters offer similar prayers before digging for clay.

Figure 9. Local Kneading Process

In looking for workable clay, its quality must be considerably plastic to assume any shape that it will be subjected to. The indigenous potter may use a simple clay test, for instance, rolling a coil of clay around the finger to determine whether the clay is suitable. Its suitability depends upon whether it cracks or not. If it cracks excessively then the clay is not plastic enough to be used for pottery.

Figure 10. Well Kneaded Clay on Inverted Pot

Since the production involves the use of mould, building of the remaining parts take only a few minutes. Coils of clay are added when the pot is still standing upright on the supporting clay base. Lines made in the process of adding coils, are pulled and smoothened over with broken piece of calabash or corn stock. The area which the potter needs to do serious work is on the rim of the pot.

Figure 11. Spreading Clay on Inverted Pot

At this point, the potter presses much coils of clay on the pot in order to have enough clay for building the rim effectively. After placing enough coils of clay on the edge of the pot, the potter perfects it using a piece of fresh leaf, which has been soaked in water. This action is skilfully repeated until the rim is perfectly shaped and smoothened.

Figure 12. The Half Built Pot removed from the Inverted Pot

Figure 13. Finished Pot

Pot-purit and Heritage Ceramics are located in Lagos, Atamora pottery centre is located in Osun State, and Saubana and Sons' pottery located within the Ibadan metropolis were considered as point of discussion in this paper. The findings reported interprets the technological evolution of these ceramic enterprises, assessment of their production facilities and know-how.

Figure 14. Chief Potter of Pot-Purit Pottery Centre

Mr. D. O. Owolabi established this cottage ceramic industry in 2004 at Ikeja in Lagos, South-western Nigeria where various types of wares ranging from flower vases and planters, to lamp shades were made. He is a graduate of College of Education, Ilorin, Nigeria, where he studied ceramics as an option in applied art. He undertook a four month practical skill apprenticeship in throwing on the potter's wheel, hand building and casting at Sweet Art Ceramics studio, Lagos.

Figure 15. Chief Potter of Pot-Purit Pottery Centre

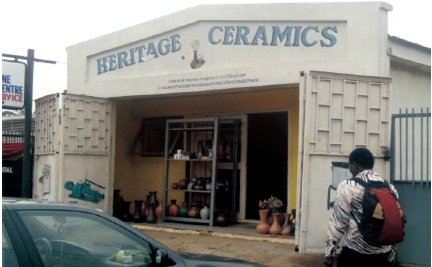

In the year 2002,Heritage Ceramics Nigeria Ltd. started its operation as ceramic equipment sales outlet and servicing centre in Lagos, Western Nigeria. It started its operation in ceramic studio with the name Stack Ceramics in the United Kingdom in 1984. It then changed its name to Heritage Ceramics.

Figure 16. Heritage Ceramics Studio Environment

Heritage Ceramics is currently managed by Mr. Odion Ogogo. The company has an emerging contemporary studio with a production style that synthesizes home grown style with the European pottery techniques using modern ceramic equipment that include electric potters' wheel, gas kiln, pug mill, wad box. etc.

Figure 17. Heritage Sales Outlet

Atamora Pottery Centre started its production operation in 1985 at Ile-Ife, Osun State as Country Crafts Ltd by Mr.Ibukunoluwa Ayoola. In 1998 the studio's location was moved to Anifowose Street, Ikeja-Lagos and later changed the name to Sweet Art Nigerian Limited. A pottery village project was later set up at the Atamora Village in Osun State in September 2006. The centre produces ornamental and aesthetic wares of varied shapes and sizes. The decorative techniques used include incision, appliqué decoration, sprigging and stamping, simulated textures and burnishing. The pottery centre sources her raw materials from the surrounding villages. The villages have advantage of clay heap due to land clearance resulting from road construction.

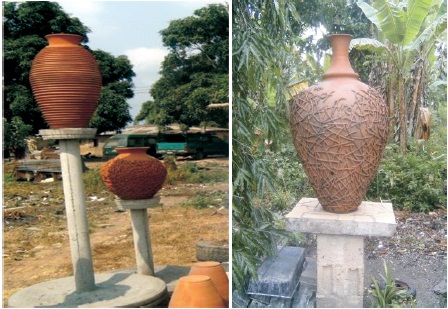

Figure 18. Wheel-Thrown Large Pottery Vases Produced in Atamara Pottery Center (Kashim & Adelabu, 2013)

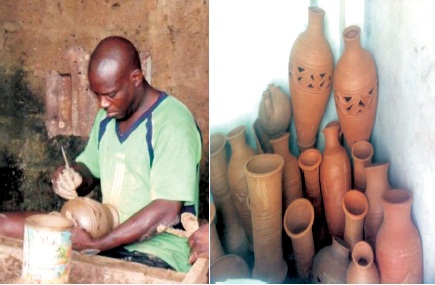

Mr. Ogundele found the centre, he was trained at Ocean 5 Ceramics Industry, at Ogunmakin, Owode local government area of Ogun State in 1985. He set up his ceramic studio in 1993 with full operation the same year. It is located in Ibadan, South West Nigeria. The centre produces ceramic wares that serve as ornamentation and interior decorations such as lamp stands, planters, flower vases and wall handling vases (Figure 19).

Figure 19. The Manager of Saubana and Sons Ceramics Working and Unglazed Pottery Wares Produced at Saubana and Sons Ceramics. (Kashim & Adelabu, 2013)

Without doubt, the people of South Western Nigeria had already acquired the necessary technical competencies in their various industrial activities before the grip of British colonization. They had the basic tools and were proficient in various methods of pottery production which had been transferred from one generation to another. It is clear that the modern western pottery is gradually having a firm entry into the various spaces in the south west of Nigeria. However, this does not suggest that we should worry about the onslaught of Western ceramics technologies on the traditional pottery; but rather, it advocates and questions the need to introduce pottery technology centres in the south west where young people and adults alike can experience the power and use of clay. It is argued that this will advance development, centred on innovation, local initiative and all round understanding of issues in all aspects of life.