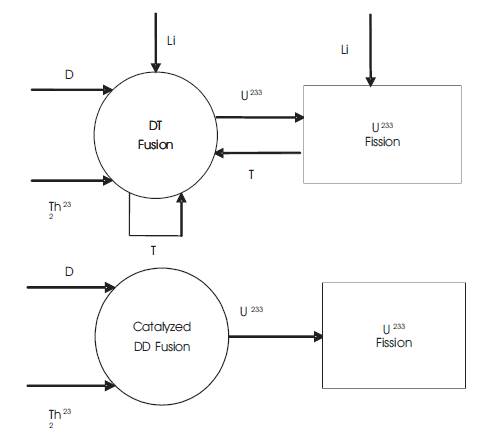

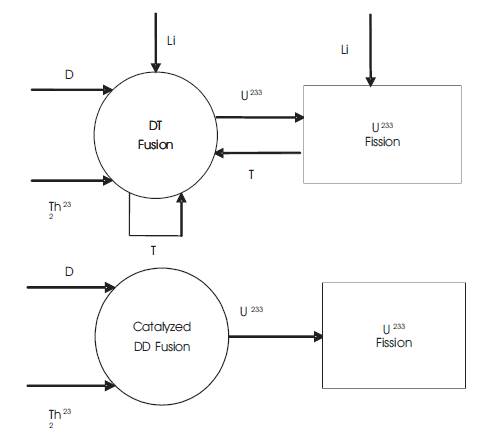

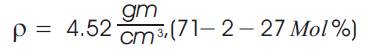

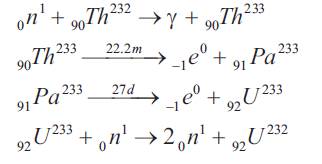

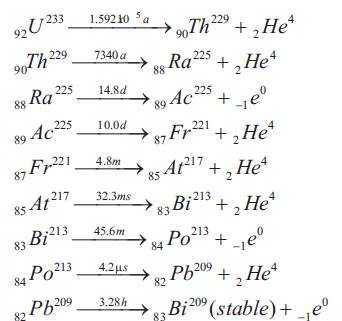

Figure 1. Material flows in the DT (top) and Catalyzed DD fusion- fission hybrid (bottom) alternatives with U233 breeding from Th232 .

The thorium fusion fission hybrid is discussed as a sustainable longer term larger resource base to the fast breeder fission reactor concept. In addition, it offers a manageable waste disposal process, burning of the produced actinides and serious nonproliferation characteristics. With the present day availability of fissile U235 and Pu239 , and available fusion and accelerator neutron sources, a new look at the thorium-U233 fuel cycle is warranted. The use of the thorium cycle in a fusion fission hybrid could bypass the stage of fourth generation breeder reactors in that the energy multiplication in the fission part allows the satisfaction of energy breakeven and the Lawson condition in magnetic and inertial fusion reactor designs. This allows for the incremental development of the technology for the eventual introduction of a pure fusion technology.The nuclear performance of a fusion-fission hybrid reactor having a molten salt composed of Na-Th-F-Be as the blanket fertile material and operating with a catalyzed Deuterium-Deuterium (DD) plasma is compared to a system with a Li-Th-F-Be salt operating with a Deuterium-Tritium (DT) plasma. In a reactor with a 42-cm thick salt blanket followed by a 40-cm thick graphite reflector, the catalyzed DD system exhibits a fissile nuclide production rate of 0.88 Th(n,γ) reactions per fusion source neutron. The DT system, in addition to breeding tritium from lithium for the DT reaction yields 0.74 Th(n,γ) breeding reactions per fusion source neutron. Both approaches provide substantial energy amplification through the fusion-fission coupling process. Such an alternative sustainable paradigm or architecture would provide the possibility of a well optimized fusion-fission thorium hybrid using a molten salt coolant for sustainable long term fuel availability with the added advantages of higher temperatures thermal efficiency for process heat production, proliferation resistance and minimized waste disposal characteristics.

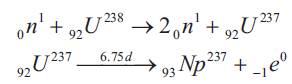

The thorium fission fusion hybrid is discussed as a sustainable longer term and larger resource base to the fast breeder fission reactor concept and as an early introduction of fusion energy. In addition, it offers a manageable waste disposal process, burning of the produced actinides and serious nonproliferation characteristics. A first generation thorium hybrid would use the DT fusion reaction as a neutron source instead of the fissile isotopes U235 and/or Pu239 as external seed material feeds, breeding tritium from lithium. A second generation would use the catalyzed or the semi-catalyzed DD fusion reaction eliminating the need for tritium breeding and providing a practically unlimited supply of the deuterium at 150 ppm in water from the world oceans. Either system could use the U233 bred from Th232 for power generation onsite or for export to satellite smaller-size fission reactors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Material flows in the DT (top) and Catalyzed DD fusion- fission hybrid (bottom) alternatives with U233 breeding from Th232 .

The nuclear performance of a fusion-fission hybrid reactor having a molten salt composed of Na-Th-F-Be as the blanket fertile material and operating with a catalyzed Deuterium-Deuterium (DD) plasma is compared to a system with a Li-Th-F-Be salt operating with a Deuterium- Tritium (DT) plasma. In a reactor with a 42-cm thick salt blanket followed by a 40-cm thick graphite reflector, the catalyzed DD system exhibits a fissile nuclide production rate of 0.88 Th(n, γ) reactions per fusion source neutron. The DT system, in addition to breeding tritium from lithium for the DT reaction yields 0.74 Th(n, γ) breeding reactions per fusion source neutron. Both approaches provide substantial energy amplification through the fusion-fission coupling process [1].

The catalyzed DD fusion approach to U233 breeding from Th232 offers distinct advantages. It eliminates the need for breeding tritium from lithium in the blanket. The requirement of tritium storage and its environmental leakage hazard are eliminated. Any tritium produced in the plasma of the catalyzed DD cycle can be directly injected into the plasma, so the active tritium inventory in the plasma loop is reduced by a factor of 3 compared with the DT fusion cycle. In addition, the competition for the available neutrons to compete for fusile and fissile breeding as occurs in the DT system is eliminated, leading to higher fissile breeding in the catalyzed DD cycle. Continuous extraction of the bred U233 and its Pa233 precursor from a molten salt would lead to a blanket relatively clean from fission products contamination, neutron poisoning and power swings caused by fissioning of the produced U233 as would occur in a solid blanket[2].

The thorium fission fuel cycle was investigated over the period 1950-1976 in the Molten Salt Breeder Reactor (MSBR) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) as well as in the pilot Shippingport fission reactor plant, which was a replica of a naval reactor design, and operated for 5 years on a single load of fuel and ended the run with more bred fissile fuel U233 fuel than the fissile U235 feed that it was started with.

The existing U238 -U235 fuel cycle has been favored to the Th232 -U233 for historical reasons. The early reactors needed to be powered using the U235 isotope that occurs in natural uranium to produce Pu239 from U238 . Thorium could not have been used since it is fissionable but not fissile to build a self sustained chain reaction.

In a natural-uranium fuelled reactor using heavy water D2 O as a coolant/moderator, about 1 gram per day of Pu239 is produced by neutron capture in U238 per MW of thermal power at low U235 burnup. Production of the fissile U233 isotope requires the irradiation of the fertile Th232 isotope in a neutron spectrum. The thermal neutron absorption cross section of Th232 is 3 times that of U238 , and at the maximum 7 percent ThO2 needed to maintain criticality in a Heavy Water Reactor (HWR), only 0.2 gm/day per MW of U233 can be produced at low fuel burnup rates below 1,000 thermal megawatts per ton of heavy U metal (MWd / tU). Thus most of the fissile breeding in a HWR would be as Pu239 and not as U233.

With the availability of uranium enrichment capabilities, the fissile production can be shifted towards U233 production with highly enriched U235 fuel. In fact, the USA produced most of its fissile Pu239 as well as fusile tritium in its heavy water reactors at Savannah River using highly enriched naval reactors fuel as a driver neutron source and depleted uranium metal and a LiAl alloy as target elements.

With the present day availability of fissile U235 and Pu239 , and available fusion and accelerator neutron sources, a new look at the thorium cycle is warranted. Since no more than 7 percent of ThO2 fuel can be added to a HWR before criticality would not be achievable, this suggests that fusion and accelerator sources are the appropriate alternative for the implementation of the Th fuel cycle.

India, considering its large thorium resources but limited uranium resources has adopted a three stages plan to implement the thorium fuel cycle. The first stage involves the use of HWRs fueled by natural uranium and Light Water Reactors, LWRs fueled by Low Enriched Uranium (LEU). In the second stage, the plutonium extracted from the spent fuel of these reactors would be used as a startup fuel for liquid sodium cooled fast reactors. In the third stage, the U233 produced by neutron capture in Th232 blankets in the fast breeder reactors would be mixed with thorium and used to start up HWRs and High temperature Gas Cooled Reactors (HTGRs) using a closed U233 -Th232 fuel cycle for the long term.

Whereas the U233 -Th232 fuel cycle is undergoing a grassroots scientists and engineers as well as members of the public revival as a replacement of the existing LWRs system, there exists a highly promising approach in its use in fusion-fission hybrid reactors as an eventual bridge and technology development for future pure fusion reactors, bypassing the intermediate stage of the fast fission breeder reactors.

It may be a suitable time to leap to the proposed approach to take advantage of the Th cycle benefits in the form of a well optimized fission-fusion thorium hybrid. Such an alternative sustainable paradigm or architecture would provide the possibility of long term fuel availability with the added advantages of higher temperatures thermal efficiency for process heat production, the possibility of dry cooling in arid areas of the world, proliferation resistance and minimal waste disposal characteristics.

High Temperature graphite moderated reactor designs have historically used thermal breeding within the Th232 -U233 fuel cycle. The smaller modular designs of HTGRs have been under development beginning with a design originating in Germany in 1979. The supporting HTGR technology has been under development with major programs in the UK, the USA and Germany from the 1950's through the early 1990's. Important milestones have been achieved in the design and successful operation of three steel vessel HTGRs during the 1960's and 1970's, and in the production and demonstration of robust, high quality fuel and other key elements of the technology.

The technology has developed along two distinct paths: pebble bed fuel consisting of ceramic spheres 6 cm in diameter with continuous refueling, and prismatic fuel consisting of hexagonal blocks approximately 35 cm across the flats and 75 cm in height with periodic batch refueling. Both fuel systems utilize ceramic coated microparticles of less than 1 millimeter in diameter.

The pebble Bed Modular Reactor conceptual design, PBMR was pursued jointly by the Exelon Corporation in the USA and South Africa's state owned utility Eskom. This concept is a high temperature helium cooled reactor with unit sizes of 110 MWe. These small sizes can be factory built before assembly at a site.

This design depends on fuel in the form of pebbles 6 cm in diameter. About 400,000 of these pebbles lie within a graphite lined vessel that is 20 m high and 20 m in diameter. Each pebble contains about 15,000 fuel particles where the fuel is enclosed in layers of pyrolitic graphite and silicon carbide.

The use of graphite as fuel element cladding, moderator, core structural material, and reflector, provides the reactor with a high degree of thermal inertia. A core melt situation would be practically unlikely, since a large difference exists between the normal average operating temperature of 1,095 degrees C, and the maximum tolerable fuel temperature of 2,800 degrees C.

Helium at a temperature of about 500 degrees C is pumped in at the top of the reactor, and withdrawn after sufficient burnup from the bottom of the reactor. The coolant gas extracts heat from the fuel pebbles at a temperature of 900 degrees C. The gas is diverted to three turbines. The first two turbines drive compressors, and the third drives an electrical generator from which electrical power is produced.

Upon exit from the compressors or generator, the gas is at 530 degrees C. It passes through recuperators where it loses excess energy and leaves at 140 degrees C. A water cooler takes it further to about 30 degrees C. The gas is then repressurized in a turbo-compressor. It then moves back to the regenerator heat-exchanger, where it picks up the residual energy before being fed to the reactor.

Refueling is done online, eliminating refueling outages. The PBMR would shut down every few years for maintenance of other mechanical parts of the plant. The staff would be constantly taking pebbles out of the bottom, checking their burnup, eliminating any leakers, and then reloading them back from the top, or adding fresh pebbles to replace the discarded ones..

The spent fuel pebbles are passed pneumatically to large storage tanks at the base of the plant. This storage space can hold all spent fuel throughout the plant's life. These tanks can hold the fuel for 40 to 50 years after shutdown. About 2.5 million walls are normally used over the 40 years design life of a typical reactor. The silicon carbide coating on the fuel particles can isolate the fission products, at least in theory for a million years. For permanent storage, these pebbles are easier to store than fuel rods from PWRs.

The PBMR is expected to have an overall thermal efficiency of bout 40-42 percent. It operates at a low power density of less than 4.5 MW/m3 , compared with a value of 100 for a PWR.

The economic advantage of the PBMR is that it can allow a utility to make a decision on investing about 120 million dollars rather than the 2-3 billion dollars for other power plants. In addition, the construction time can be reduced to the 18-36 months level as opposed to the 5 or more years for light water reactors. The operating costs of the concept because of the staffing characteristics and the lower fuel costs. It can satisfy the information technology needs which are increasing the load demand in the USA at 4-4 1/2 percent rate per year, for instance around Chicago.

It possesses a high degree of inherent safety. The worst case scenario would produce temperatures below fuel damage temperatures.

The design provides a containment structure provide for regulatory needs only the reason is that the type of accidents envisioned would take hours to days to develop, as compared to minutes in PWRs. In the USA a Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) policy statement designated as SECY 93-092, provides guidance in this regard. It concludes that conventional containment is not needed for such a design. Nevertheless, the PBMR design allows for the release of the helium coolant in the case of a loss of coolant accident. The containment structure is there to intercept any fission products release within days of the initiation of any accident.

The design would require a smaller Emergency Planning Zone (EPZ). The control rods are used only for compensating for the initial heat up and for achieving full cold shutdown. For temperature control, the helium pressure is lowered or raised. To decrease the power level, the temperature is decreased by increasing the helium pressure and vice versa.

In a bridging to a helium economy in the future, high temperature systems can be used to dissociate water into oxygen and hydrogen on a global scale. This would satisfy in a nonpolluting manner the needs of both industrialized and developed nations. Expectations are for the doubling of electricity demand worldwide by 2020.

In solid fuel reactors the fission product Xenon135 acts as a neutron poison and remains confined in the fuel. In the fluid fuelled thorium cycle it can be readily removed.

The use of a molten salt offers the possibility of developing a sophisticated reprocessing approach eliminating the Np, Am and Cm actinides from the cycle without criticality constraints. One can think about feeding them back into the reactor for eventual fissioning. Their fissioning would be more prominent in a fast neutron spectrum in the case of the hybrid than it would be in a thermal neutron spectrum in the case of a fission system. The current molten salt reprocessing involves:

a) The chemical separation of the bred U233 by fluorination to the uranium hexafluoride gas U233 F6 , and later its reduction into the U233 F4 powder for reincorporation into the liquid fuel stream.

b) The strong neutron absorber bred Pa233 is stripped using metallic bismuth, and allowing it enough time to decay into U233 to be returned to the fuel stream again.

c) The remaining salt is distilled to remove the lighter fission products, with the transuranics remaining in the stream to be burned in the reactor.

As one of six Fourth Generation reactors concepts under consideration, the Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) system produces fission power in a circulating molten salt fuel mixture with an epithermal neutron spectrum reactor with graphite core channels, and a full actinide recycle fuel cycle. The MSR can be designed to be a thermal breeder using the Th232 to U233 fuel cycle.

In the MSR system, the fuel is a circulating liquid mixture of sodium, zirconium, and uranium fluorides. The molten salt fuel flows through graphite core channels, producing an epithermal spectrum. The heat generated in the molten salt is transferred to a secondary coolant system through an intermediate heat exchanger, and then through a tertiary heat exchanger to the power conversion system. The reference plant has a power level of 1,000 MWe. The system has a coolant outlet temperature of 700 oC, possibly ranging up to 800o C, affording improved thermal efficiency.

The closed fuel cycle can be tailored to the efficient burnup of plutonium and the minor actinides. The MSR's liquid fuel allows addition of actinides such as plutonium and avoids the need for fuel fabrication. The actinides and most fission products form fluorinides in the liquid coolant. Molten fluoride salts have excellent heat transfer characteristics and a very low vapor pressure, which reduce stresses on the vessel and piping.

An Engineered Safety Feature, ESF involves a Freeze Plug where the coolant is cooled into a frozen state. Upon an unforeseen increase in temperature, this plug would melt leading to the dumping of the coolant into emergency dump tanks. In the absence of moderation by the graphite, the coolant would reside there in a subcritical safe state until pumped back into the core.

Research and development on that concept addresses the selection of a fuel salt with small neutron cross section of the fuel solvent, radiation stability, and a negative temperature coefficient of reactivity. It needs a low melting point good thermal stability, low vapor pressure and adequate heat transfer and viscosity coolant. The secondary salt must be corrosion resistant to the primary salt. Graphite as a moderator would have to be replaced every four years due to radiation damage to its matrix.

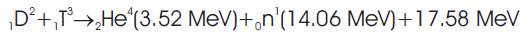

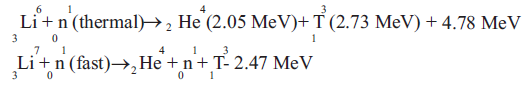

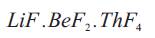

For an immediate application of the fusion hybrid using the Th cycle, the DT fusion fuel cycle can be used:

The tritium would have to be bred from the abundant supplies of lithium using the reactions

In this case a molten salt containing Li for tritium breeding as well as Th for U233 breeding can be envisioned

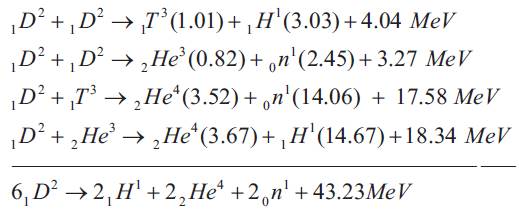

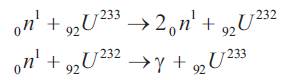

For a practically unlimited supply of deuterium from water at a deuterium to hydrogen ratio of D/H = 150 ppm in the world oceans, one can envision the use of the catalyzed DD reaction in the fusion island:

with each of the five deuterons contributing an energy release of 43.23/6 = 7.205 MeV.

For plasma kinetic reactions temperatures below 50 keV, the DHe3 reaction is not significant and the energy release would be 43.23 - 18.34 = 24.89 with each of the five deuterons contributing an energy release of 24.89/5 = 4.978 MeV

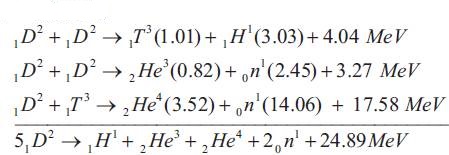

In this case, there would be no need to breed tritium, and the lithium can be replaced by Na in a molten salt with the following composition:

NaF .BeF2 .ThF4

With a density and percentage molecular composition of:

A one dimensional computational model considers a plasma cavity with a 150 cm radius. The plasma neutron source is uniformly distributed in the central 100 cm radial zone and is isolated from the first structural wall by a 50 cm vacuum zone.

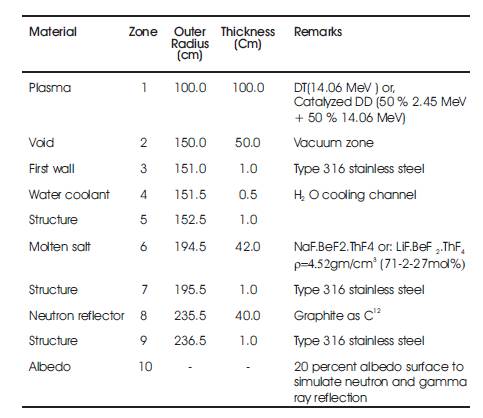

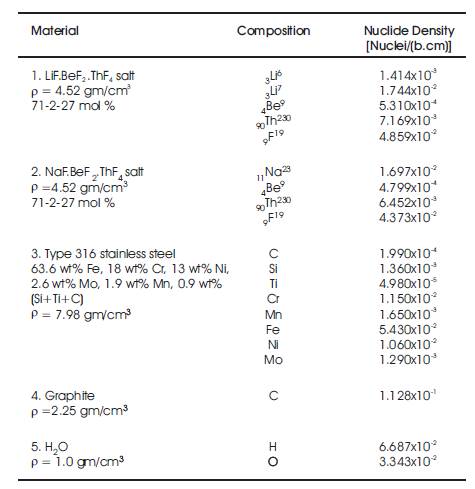

The blanket module consists of a 1 cm thick Type 316 stanless steel first structural wall that is cooled by a 0.5 cm thick water channel, a 42 cm thick molten salt filled energy absorbing and breeding compartment, and a 40 cm thick graphite neutron reflector(Table 1).

Table 1. Fusion-Fission Reactor Geometrical Model.

The molten salt and graphite are contained within 1 cm thick Type 316 stainless steel structural shells(Table 2).

Table 2. Fusion-Fission Material Compositions.

Computations were conducted using the one dimensional discrete ordinates transport ANISN code with a P3 Legendre expansion and an S12 angular quadrature.

The catalyzed DD system exhibits a fissile nuclide production rate of 0.880 Th(n, γ) reactions per fusion source neutron. The DT system, in addition to breeding tritium from lithium for the DT reaction yields 0.737 Th(n, γ) breeding reactions per fusion source neutron. Both approaches provide substantial energy amplification through the fusion-fission coupling process(Table 3).

Table 3. Fissile and Fusile Breeding for Sodium and Lithium Salts in DT and DD Symbiotic Fusion-Fission Fuel Factories. Blanket thickness = 42 cm, reflector thickness =40 cm; no structure in the salt region.

The largest Th(n,γ) reaction rate (0.966) occurs when the sodium salt is used in conjunction with the DT reaction. For this case, however, the tritium required to fuel the plasma must be supplied to the system, since that produced in the blanket would be negligible (3.18x10-3 ). A system of such kind has been proposed and studied by Blinken and Novikov.

For the catalyzed DD plasma, the Th(n,γ) reaction rate is 0.880 in the sodium salt compared with 0.737 obtained in the DT system using the lithium salt. For the DT system the tritium production rate is 0.467 tritium nuclei per source neutron. The tritium production rate is too low to sustain the DT plasma, and an extra supply of the isotope is required to supplement the plasma. This could be internal by allowing some fissions to occur in the blanket supplying extra neutrons, or this could be external in the external satellite fission reactors producing the needed difference as a byproduct and feeding it back to the DT plasma.

The fissile fuel production rate is higher in the DD system because of the absence of lithium in the salt that would introduce a competition between the Th(n,γ) and the Li6 (n,T) reactions.

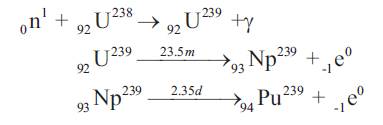

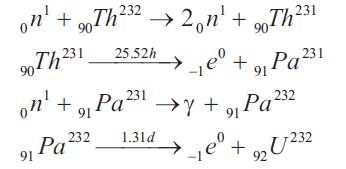

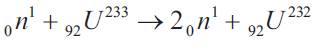

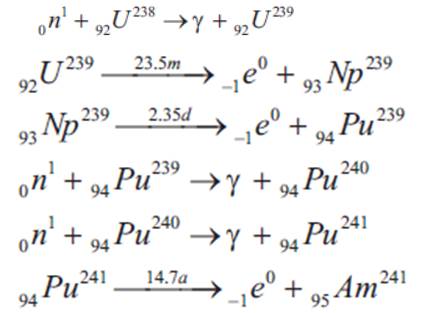

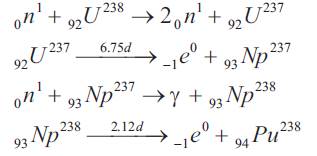

There has been a new interest in the Th cycle in Europe and the USA since it can be used to increase the achievable fuel burnup in LWRs in a once through fuel cycle while significantly reducing the transuranic elements in the spent fuel. A nonproliferation as well as transuranics waste disposal consideration is that just a single neutron capture reaction in U238 is needed to produce Pu239 from U238 :

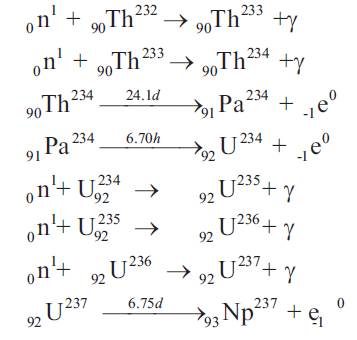

whereas a more difficult process of fully 5 successive neutron captures are needed to produce the transuranic Np237 from Th232 :

This implies a low yield of Np237 however, as an odd numbered mass number isotope posing a possible proliferation concern; whatever small quantities of it are produced, provisions must be provided in the design to have it promptly recycled back for burning in the fast neutron spectrum of the fusion part of the hybrid.

In fact, it is more prominently produced in thermal fission light water reactors using the uranium cycle and would be produced; and burned, in fast fission reactors through the (n, 2n) reaction channel with U238 according to the much simpler path:

A typical 1,000 MWe Light Water Reactor (LWR) operating at an 80 percent capacity factor produces about 13 kgs of Np237 per year.

This has led to suggested designs where Th232 replaces U238 in LWRs fuel and accelerator driven fast neutron subcritical reactors that would breed U233 from Th232 .

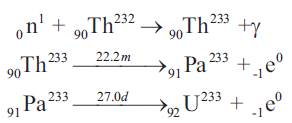

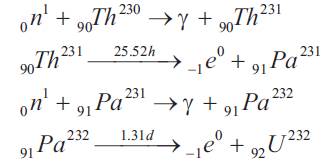

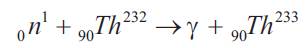

Thorium (Th) is named after Thor, the Scandinavian god of war. It occurs in nature in the form of a single isotope: Th232 . Twelve radioactive isotopes are known for Th. It occurs in Thorite (ThSiO4) and Thorianite (ThO2 + UO2 ). It is 3 times as abundant as uranium in the earth's crust and as abundant as lead and molybdenum. It is commercially obtained from the monazite mineral containing 3-9 percent ThO2 with other rare-earths minerals. Its large abundance will make it in the future valuable for electrical energy generation, sea water desalination and hydrogen production with supplies exceeding both coal and uranium combined. This would depend on breeding of the fissile isotope U233 from the fertile isotope Th232 according to the breeding reactions:

Together with uranium, the thorium's radioactive decay chain leads to stable lead isotopes with a half-life of 1.4 x 1010 years for Th232 . It contributes to the internal heat generation in the Earth.

As Th232 decays into the stable Pb208 isotope, Radon220 , initially designated as Thoron, forms in the chain. Rn220 has a low boiling point and exists in gaseous form at room temperature. It poses a radiation hazard through its own daughter nuclei. Radon from uranium and thoron from thorium tests are needed to check for their presence in new homes that are possibly built on rocks like granite or sediments like shale or phosphate rock containing significant amounts of uranium and thorium and their decay daughter nuclei. Adequate ventilation of homes that are over-insulated becomes a design consideration in this case.

Thorium, in the metallic form, can be produced by reduction of ThO2 using calcium or magnesium in crucibles. Also by electrolysis of anhydrous thorium chloride in a fused mixture of Na and K chlorides, by calcium reduction of Th tetrachloride mixed with anhydrous zinc chloride, and by reduction with an alkali metal of Th tetrachloride.

Thorium is the second member of the actinides series in the periodic table of the elements. When pure, it is soft and ductile, can be cold rolled and drawn and it is a silvery white metal retaining its luster in air for several months. If contaminated by the oxide, it tarnishes in air into a gray then black color.

Thorium oxide has the highest melting temperature of all the oxides at 3,300 degrees C. Just a few other elements and compounds have a higher melting point such as tungsten and tantalum carbide. Water attacks it slowly, and acids do not attack it except for hydrochloric acid.

Thorium in the powder form is pyrophyric and can burn in air with a bright white light. In portable gas lights, the Welsbach mantle is prepared with ThO2 with an added 1 percent cerium oxide and other ingredients. As an alloying element in magnesium, it gives high strength and creep resistance at high temperatures. Tungsten wire and electrodes used in electrical and electronic equipment such as electron guns in x-ray tubes or video screens are coated with Th due to its low work function and associated high electron emission. Its oxide is used to control the grain size of tungsten used in light bulbs and in high temperature laboratory crucibles. Glasses for lenses in cameras and scientific instruments are doped with Th to give them a high refractive index and low light dispersion. In the petroleum industry, it is used as a catalyst in the conversion of ammonia to nitric acid, in oil cracking, and in the production of sulfuric acid.

Thorium is more abundant than uranium and provides a fertile isotope for breeding of the fissile uranium isotope U233 in a thermal or fast neutron spectrum. In the Shippingport reactor it was used in the oxide form. In the HTGR it was used in metallic form embedded in graphite. The MSBR used graphite as a moderator and hence was a thermal breeder and a chemically stable fluoride salt, eliminating the need to process or to dispose of fabricated solid fuel elements. The fluid fuel allows the separation of the stable and radioactive fission products for disposal. It also offers the possibility of burning existing actinides elements and does need an enrichment process like the U235 -Pu239 fuel cycle.

Thorium is abundant in the Earth's crust, estimated at 120 trillion tons. The monazite black sand deposits are composed of 12 percent of thorium. It can be extracted from granite rocks and from phosphate rocks, rare earths, tin ores, coal ash and uranium mines tailings. It could also be extracted from the ash of coal power plants.

A 1,000 MWe coal power plant generates about 13 tons of thorium per year in its ash. Each ton of thorium can in turn generate 1,000 MWe of power in a well optimized thorium reactor. Thus a coal power plant can conceptually fuel 13 thorium plants of its own power. From a different perspective, 1 pound of Th has the energy equivalent of 5,000 tons of coal. There are 31 pounds of Th in 5,000 tons of coal. If the Th were extracted from the coal, it would thus yield 31 times the energy equivalent of the coal.

The calcium sulfate or phospho-gypsum resulting as a waste from phosphate rocks processing into phosphate fertilizer contains substantial amounts of unextracted thorium and uranium.

Uranium mines with brannerite ores generated millions of tons of surface tailings containing thoria and rare earths.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), as of 2008, estimated that the USA has reserves of 915,000 tons of thorium ore existing on properties held by Thorium Energy Inc. in Montana and Idaho. This compares to a previously estimated 160,000 tons for the entire USA.

The next highest global thorium ores estimates are for Australia at 300,000 tons and India with 290,000 tons.

The need for U235 enrichment for nuclear naval propulsion and for nuclear devices using both U235 and Pu239 were factors in favoring the adoption of the U235 fuel cycle. Historically, among the nuclear energy pioneer scientists, Enrico Fermi advocated the use of the U235 -Pu239 fuel cycle, whereas Eugene Wigner favored the longer term Th232 -U233 fuel cycle. Pu239 is considered a better fuel for fast reactors using liquid metals such as sodium or lead as coolants. The thorium cycle technology was tested in the Shippingport pilot plant during the 1970-1980 period.

The MSBR operates at low pressures implying a higher level of safety than existing Light Water Reactors (LWRs) where depressurization can lead to the water coolant flashing into steam leading to a Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA). It can operate at high temperatures, implying a higher thermal efficiency reaching 50 percent compared with 33 percent in the LWR system. It offers the possibility of high temperature process heat production for hydrogen production as a fission energy carrier for use as a transportation fuel in a fuel cells based infrastructure.

The MSBR was 100-300 times more fuel efficient than the LWR, reducing the volume of the disposed fission products waste and using for centuries the existing stockpiles of thorium and uranium. Over the last 40 years, $25 million have been collected into a trust fund from the electrical utilities to fund waste disposal facilities. A part of these could be used for the development of the thorium fuel cycle preventing the creation of new long-lived nuclear waste.

The following advantages of the thorium fuel cycle over the U235 -Pu239 fuel cycle can be enumerated:

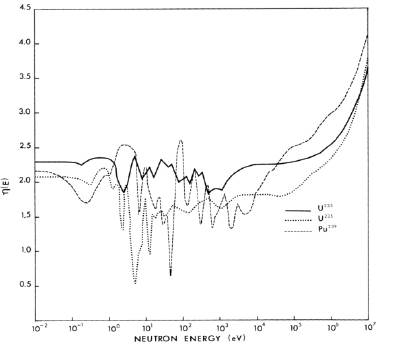

1. Breeding is possible in both the thermal and fast parts of the neutron spectrum with a regeneration factor of η > 2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regeneration Factor as a Function of Neutron Energy for the different Fissile Isotopes

2. Expanded nuclear fuel resources due to the higher abundance of the fertile Th232 than U238. The USA proven resources in the state of Idaho amount to 600,000 tons of 30 percent of Th oxides. The probable reserves amount to 1.5 million tons. There exists about 3,000 tons of already milled thorium in a USA strategic stockpile stored in Nevada.

3. Lower nuclear proliferation concerns due to the reduced limited needs for enrichment of the U235 isotope that is needed for starting up the fission cycle and can then be later replaced by the bred U233 . The fusion fission fusion hybrid totally eliminates that need.

4. A superior system of handling fission products wastes than other nuclear technologies and a much lower production of the long lived transuranic elements as waste. One ton of natural Th232 , not requiring enrichment, is needed to power a 1,000 MWe reactor per year compared with about 33 tons of uranium solid fuel to produce the same amount of power. The thorium just needs to be purified then converted into a fluoride. The same initial fuel loading of one ton per year is discharged primarily as fission products to be disposed of for the fission thorium cycle.

5. Ease of separation of the lower volume and short lived

6. Higher fuel burnup and fuel utilization than the U235 -Pu239 cycle.

7. Enhanced nuclear safety associated with better temperature and void reactivity coefficients and lower excess reactivity in the core.

8. With a tailored breeding ratio of unity, a fission thorium fuelled reactor can generate its own fuel, after a small amount of fissile fuel is used as an initial loading.

9. The operation at high temperature implies higher thermal efficiency with a Brayton gas turbine cycle instead of a Joule or Rankine steam cycle, and lower waste heat that can be used for desalination or space heating. If thermal efficiency can be sacrified, an open air cooled cycle can be contemplated eliminating the need for cooling water and the associated heat exchange equipment.

10. A thorium cycle for base-load electrical operation would a perfect match to peak-load cycle wind turbines generation. The produced wind energy can be stored as compressed air which can be used to cool a thorium open cycle reactor, substantially increasing its thermal efficiency, yet not requiring a water supply for cooling.

11. The unit powers are scalable over a wide range for different applications such as process heat or electrical production. Units of 100 MWe each can be designed, built and combined for larger power needs. 12. Operation at atmospheric pressure without pressurization implies the use of standard equipment with a lower cost than the equipment operated at high pressure in the LWRs cycle.

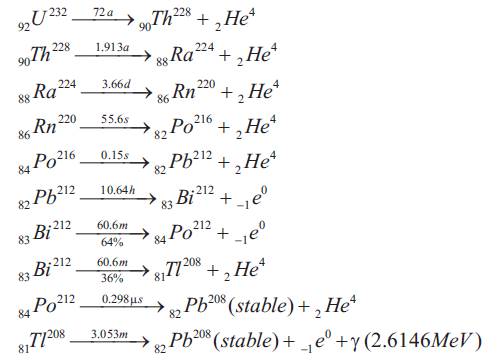

The hard gamma rays associated with the decay chain of the formed isotope U232 with a half life of 72 years and its spontaneous fission makes the U233 in the thorium cycle with high fuel burnup a higher radiation hazard from the perspective of proliferation than Pu239 [3].

The U232 is formed from the fertile Th232 from two paths involving an (n, 2n) reaction, which incidentally makes Th232 a good neutron multiplier in a fast neutron spectrum:

and another involving an (n,γ) capture reaction:

The isotope U232 is also formed from a reversible (n, 2n) and (n, γ) path acting on the bred U233 :

The isotope Th230 occurs in trace quantities in thorium ores that are mixtures of uranium and thorium. U234 is a decay product of U238 and it decays into Th230 that becomes mixed with the naturally abundant Th232 . It occurs in secular equilibrium in the decay chain of natural uranium at a concentration of 17 ppm. The isotope U232 can thus also be produced from two successive neutron captures TH230

The hard 2.6 MeV gamma rays originate from Tl208 isotope in the decay chain of aged U232 which eventually decays into the stable Pb208 isotope

For comparison, the U233 decay chain eventually decays into the stable Bi209 isotope

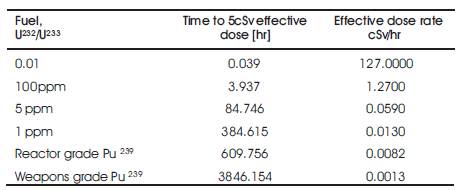

A 5-10 proportion of U232 in the U232 -U233 mixture has a radiation equivalent dose rate of about 1,000 cSv (rem)/hr at a 1 meter distance for decades making it a highly proliferation resistant cycle if the Pa233 is not separately extracted and allowed to decay into pure U233 .

The Pa233 cannot be chemically separated from the U232 if the design forces the fuel to be exposed to the neutron flux without a separate blanket region, making the design failsafe with respect to proliferation and if a breeding ratio of unity is incorporated in the design.

Such high radiation exposures would lead to incapacitation within 1-2 hours and death within 1-2 days of any potential proliferators.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) criterion for fuel self protection is a lower dose equivalent rate of 100 cSv(rem)/hr at a 1 meter distance. Its denaturing requirement for U235 is 20 percent, for U233 with U238 it is 12 percent, and for U233 denaturing with U232 it is 1 percent.

The Indian Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) had plans on cleaning U233 down to a few ppm of U232 using Laser Isotopic Separation (LIS) to reduce the dose to occupational workers.

The contamination of U233 by the U232 isotope is mirrored by another introduced problem from the generation of U232 in the recycling of Th232 due to the presence of the highly radioactive Th228 from the decay chain of U232 .

The Th232 -U233 fuel cycle in fission reactors can have a conversion ratio of larger than unity and become a net breeder of fissile material in thermal spectra if the use of burnable neutron poisons to control long term reactivity is minimized by the use of continuous fueling in a liquid salt or a slurry or the use a geometrical control of the reactivity by the control rods(Table 4).

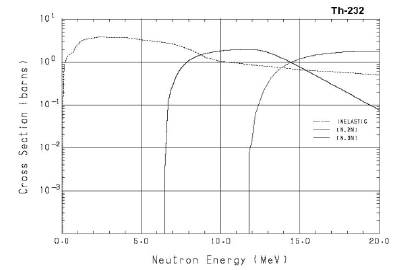

The threshold for the (n, 2n) reaction at 6 MeV and the (n, 3n) reaction would be more significant in the high energy neutron spectrum of the fusion-fission hybrid than in the case of a thermal neutron spectrum and needs to be quantified(Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Cross Section Distribution for the (n, 2n) and n( 3n) Neutron Multiplication Reactions in Th232 showing Energy Thresholds at 6.465 and 11.61 MeV. Source: JENDL.

In addition, in the hard neutron spectrum, fissions will also occur in Th232 adding more neutrons to be available for fusile as well as fissile breeding(Figure 2)

The fission spectrum average cross section is 14.46 mb, and is a much larger value of 1.181 b for a fusion 14 Mev spectrum for the (n, 2n) reaction:

and it is 4.08 mb for the (n, γ) reaction:

The U232 /U233 ratio will depend on the fraction of neutrons above the 6.465 MeV neutron energy threshold. In a fusion spectrum this fraction would be large enough to produce fuel that is unusable for weapons manufacture.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) criterion for occupational protection is an effective dose of 100 cSv (rem)/hr at a 1 meter distance from the radiation source.

It is the decay product Tl208 in the decay chain of U232 and not U232 itself that generates hard gamma rays. The Tl208 would appear in aged U233 over time after separation emitting a hard 2.6416 MeV gamma ray photon. It accounts for 85 percent of the total effective dose 2 years after separation. This implies that manufacturing of U233 should be undertaken in freshly purified U233 . Aged U233 would require heavy shielding against gamma radiation.

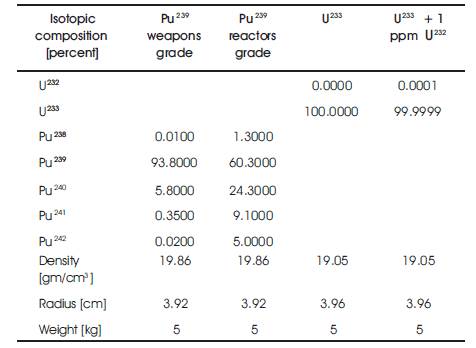

In comparison, Pu239 containing Pu241 with a half life of 14.4 years, the most important source of gamma ray radiation is from the Am241 isotope with a years half life that emits low energy gamma rays of less than 0.1 MeV in energy. For weapons grade Pu239 with about 0.36 percent Pu241 this does not present a major hazard but the radiological hazard becomes significant for reactor grade Pu239 containing about 9-10 percent Pu241 .

The generation of Pu241 as well as Pu240 and Am241 from U238 follows the following path:

Plutonium containing less than 6 percent Pu240 is considered as weapons-grade(Table 4).

The gamma rays from Am241 are easily shielded against with Pb shielding. Shielding against the neutrons from the spontaneous fissions in the even numbered Pu238 and Pu240 isotopes accumulated in reactor grade plutonium requires the additional use of a thick layer of a neutron moderator containing hydrogen such as paraffin or plastic, followed by a layer of neutron absorbing material and then additional shielding against the gamma rays generated from the neutron captures(Table 5).

Table 5. Typical Compositions of Fuels in the Uranium and Thorium Fuel Cycles [9].

Table 6. Glove Box Operation dose rate required to accumulate a limiting occupational 5 cSv (rem) dose equivalent from a 5 kg metal sphere, one year after separation at a 1/2 meter distance[8].

The generation of Pu238 and Np237 by way of (n, 2n) rather than (n,γ) reactions follows the path:

The production of Pu238 for radioisotopic sources for space applications follows the path of chemically separating Np237 from spent LWR fuel and then neutron irradiating it to produce Pu238 .

Both reactor-grade plutonium and U233 with U232 would pose a significant radiation dose equivalent hazard for manufacturing personnel as well as military personnel, which precludes their use in weapons manufacture in favor of U235 and weapons-grade Pu239 .

The molten salt has a substantial negative temperature coefficient of reactivity. As the temperature increases, the coolant's density decreases, and the power level subsequently decreases, leading to a decrease in temperature.

A freeze plug in a drain at the reactor vessel would be continuously cooled. If the cooling were stopped; caused for instance by a power failure, the plug would melt draining the entire molten salt through gravity to storage tanks shutting down the chain reaction.

The use of the thorium cycle in a fusion fission hybrid could bypass the stage of fourth generation breeder reactors in that the energy multiplication in the fission part allows the satisfaction of energy breakeven and the Lawson condition in magnetic and inertial fusion reactor designs. This allows for the incremental development of the technology for the eventual introduction of a pure fusion technology.

There is a need to start the research on vessels, piping and pumps made of ceramics or carbon aiming at operation at 900oC or higher. A 5-10 MWth test reactor would be built to test the materials to be later scaled to commercial size. Within the current state of knowledge, plants can be readily built for operation at around 650oC.

Such an alternative sustainable paradigm or architecture would provide the possibility of a well optimized fusionfission thorium hybrid for sustainable long term fuel availability with the added advantages of higher temperatures thermal efficiency for process heat production, proliferation resistance and minimized waste disposal characteristics.