Table 1. Factor Lodgings, Cronbach's Alpha Internal Consistency, Means and Standard Deviations

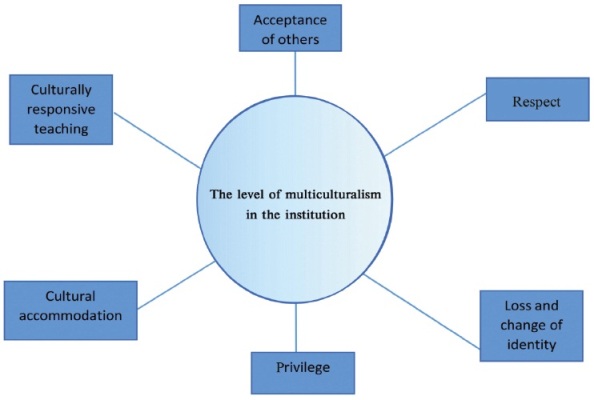

Although there is a great deal of writing about the various aspects of multiculturalism in higher education, especially about how to start implementing it on the campus, there is still a need to develop significant and credible assessment tools to examine the extent in which the goals of multiculturalism are being achieved. The questionnaire used in this study was created with this goal of assessment in mind; it provides schools with a tool that enables them to understand and improve upon the multicultural aspects of their institutions. The questionnaire was built based on the theoretical conceptions of multicultural educational research as well as on focus groups in which students and faculty discussed their experiences. The following six domains were measured: respect, acceptance of others, loss and change of identity, privilege, cultural accommodation, and Culturally Responsive Teaching / Culturally Relevant Education. The sample consisted of 314 students in five campuses on Ono Academic College in Israel and the United States. The assessment tool was found to be accurate and valid, and it thus may be reliably used to evaluate cultural diversity in an academic environment. At the micro level, using this questionnaire will give schools a keen insight into student experience and help to identify where intervention is needed in order to promote cultural diversity. At the macro level, the questionnaire formulated in this study allows institutions to gain a good understanding of the overall multicultural climate of the institution and to formulate clear objectives toward improving multicultural education.

Over the past few decades there has been a shift in higher education from what can be called “multicultural admission” to multicultural education. Schools that had previously thought that multiculturalism began and ended with equal-opportunity admission to all students whatever their social class, gender, racial, ethnic, physical or cultural characteristics, have realized that this often just leads to tokenism. As a result, there has been a growing trend toward multicultural education, which entails both moving beyond mere toleration of other cultures as well as beyond the 'deficit model' in education (whereby the goal is to facilitate the entry of students from minority cultures into “monocultural, traditional and conservative institutions of higher learning"; Pope et al. (2014, p. 5). Multicultural education begins where multicultural admission leaves off, and it involves using a variety of teaching styles, approaches, techniques and content in order to provide equal academic opportunity for students from diverse groups. Multicultural education also involves a dedicated effort toward prejudice reduction (with the help of various teaching methods and materials) and toward an inclusive school culture that empowers all students (Banks & Banks, 2010). A multicultural campus features diversity not just as nondiscrimination but as an opportunity for engagement. Multicultural education provides students “with structured learning opportunities in which they can develop their knowledge of and perspective on a diverse range of people, reflect on and challenge their own biases and stereotypes, and hone their skills for communicating, living and working within an increasingly multicultural and multiracial global community”; courses “have as their main goal the shifting and expanding of students' worldviews, even the attempt to facilitate paradigm shifts from monocultural, eurocentric ways of thinking to more inclusive, culturally aware and socially responsible perspectives” (Pope et al., 2014, pp. 1, 7).

The rise of the multicultural concept in higher education was accompanied by conservative criticism that this is a race to the bottom; i.e., consideration of multicultural aspects will necessarily lead to shallow and poor academic levels. In contrast, the view on which this paper is based is that multicultural learning does not require lowering academic standards (Blummer et al., 2018). Multiculturalism is an opportunity to expand social horizons into broad concepts of knowledge; it does not require privileging the academic norms of the dominant culture, nor does it require that the dominant culture adapts itself to minority cultures. A central goal of multicultural learning is to create a more egalitarian society, while giving space and sensitivity to the voices of different people in the society (Ippolito, 2007). In order to do so, in order not just to admit but to welcome these different voices, it is important to understand what being welcome means to the diverse groups of students who learn at our campuses.

Research on multicultural education seeks to answer certain basic questions which include:

A review of the professional literature shows that although there is a great deal of writing about the various aspects of multiculturalism in higher education, especially about how to start implementing it on campus, there is still a need to develop significant and credible assessment tools to examine the experiences of students on campuses that are devoted to multiculturalism. That is, after a school has taken steps to implement a multicultural campus, there are still not enough methods to examine the extent in which the goals of multiculturalism are being achieved. In this article we hope to contribute to the research and the assessment of multicultural education through the presentation of a quantitative survey: “ME-Q: Multicultural Education Questionnaire.”

It is possible to examine the basic parameters of multiculturalism without, at the same time thinking of multiculturalism as “one-size-fits-all” (Hartman & Zicherman, 2019; Miller & Katz, 2002). The goal of our research is to create a validated instrument that measures the specific, subjective multicultural experience of students.

The aim of the academy has always been to provoke questions concerning received wisdom, whether in the sciences, arts or humanities. Our broad research objective was to see whether (and to what extent) multicultural work caused students to question their received wisdom about the “other.” In particular, we wanted to measure the full experience of students on our multicultural campuses, in their classrooms (in relationship to their teachers and with their peers), as well as in extracurricular on-campus activities, and in their interactions with the administration (Banks & Banks, 2010). Toward this end, we sought to develop a valid measuring instrument. The process of building the instrument, i.e., the questionnaire, was twofold: it was built on theoretical conceptions of multicultural educational research as well as on focus groups in which students and faculty discussed their experiences. We used the process of grounded theory development (Charmaz, 2014; Strauss & Cobrin, 1994, 1998) to hone in on the following domains that we wanted to measure.

Each domain was comprised of a theme that emerged from the focus groups, and each was investigated as it pertained to the student's experiences with peers, teachers and administrators, in the classroom as well as in extracurricular activities.

When speaking about 'respect', the philosophical literature distinguishes between “honor” and “dignity” (Taylor, 1994; Walzer, 1997). “Honor” is intrinsically related to privilege, a kind of benefit derived from a certain position, whereas 'dignity' refers to the inherent value of each human being. The former refers to transcendence and status, and the latter to the equivalent value of each person. There is an additional definition of 'respect', and its focus is on the uniqueness and difference of the individual (Kamir, 2002). It seems that this third definition is what gives deep meaning to multiculturalism; we see value in another person's culture and we respect it. The idea here is that more than the fact that I give rights to others legally, I experience the culture of the other as valuable (Kymlicka, 1995). In terms of the students' experience, their respect depends on the attitudes of lecturers, other students and administrative personnel from different cultures with whom they come into contact.

The promise of multiculturalism is mutual respect (Walzer, 1997). All human beings need to feel that they are respected both as individuals and as members of a cultural group. A person discovers and strengthens his identity through dialogue with others, and a person who will mirror the respect that they feel (Taylor, 1994).

Students in particular crave respect; without it they will be unable to take vital intellectual and emotional risks, nor will they be able to “reflect on themselves and the society in ways that challenge their sensibilities and worldviews”. (Ravitch, 2016, p. 7). The students must be infused with respect, and the campus must provide an environment in which the particular identities of all students and teachers are respected, whatever be the race, gender and ethnicity. Mutual respect is not just allowing the 'other' to survive or allowing the 'other' access to basic human rights such as education; it also means fostering within minorities a sense of being valued.

A teacher's professionalism and skill are judged to a great extent according to the respect that the teacher conveys. In order for the students to develop multicultural capacity (knowledge, abilities and skills), they must feel a sense of respect. Respect is a value attributed to a person by themselves or by those around them and it is the key to multicultural learning.

A sense of respect for students is important in their motivation to study. Students who believe that their voice is heard and contributes to the learning climate have an increased self-esteem (Celkan et al., 2015). The sense of respect affects how students evaluate the effectiveness of learning. Students are willing to invest more in learning and to work harder to fully understand what they learn when they feel a sense of respect from their lecturer. In this way, students' sense of respect is a bridge between teaching and learning (Gay, 2003).

During our focus groups, students spoke very loudly about their experience of being honored or “dishonored” denigrated. We heard this voice consistently in all of the minority focus groups. While students spoke about their professors in terms of whether they were interesting, tough graders, and gave lot of work, more than anything we heard them saying: "he respects me", or "she respects us”, where "me" and "us" refer broadly to the student's cultural, political, national or religious identity group. This strong emphasis on respect reflects the place of honor and dignity in the Israeli context in general and in the academic experience in particular (Kamir, 2002). A focus group of teachers repeatedly noted how many students use the term 'honor' while speaking with them. One teacher mentioned that when she asked a student why he had cheated on his homework, he answered: “you do not respect me [i.e., an Arab]; no one has ever called me a cheater". We thus asked the following questions:

In the literature (Banks & Banks, 2010) it has been emphasized that the investigation of multicultural programs should not be limited to counting the number of intercultural encounters but rather should examine the extent to which a change has occurred in the perception of 'the other'. Thus, in this study, we found it appropriate to examine as an independent domain any change of consciousness of 'the other' because of the multicultural encounter.

Much of multicultural research has pointed to the fact that merely sitting in the same classroom does not change students' attitudes toward each other. Although diversity is often seen as the first step, it is not enough to change attitudes, perceptions and prejudices of the “other.” Unless there is guided interaction between groups, diversity sometimes actually increases prejudices and alienation (Tatum, 2003).

The academic ideal is not only to include the minority students on campus and to enable them to have an education; it is to develop positive attitudes to those who are different. This domain focused on three different campus-life experiences: studying with students from diverse cultures, studying with teachers from other cultures and general interactions with 'others' outside the classroom.

It is common knowledge that stereotypes grow and rankle in ignorance. People hold on to prejudices unless these prejudices are met with counter information. A theory called Dissonance Provoking Stimulus (DPS) suggests that when you meet people from different cultures your inner ground begins to shift. One of the goals of engaging with other people is to develop this DPS. For this domain, we wanted to know if and how learning from and interacting with 'others' shifted one's initial perceptions of those 'others' (Sagi, 2018). We thus asked the following questions:

Building upon the work of Banks and Banks (2010), who argued that change is not necessarily a positive development in the psychological experience of the individual but at times can be experienced as a loss, in this domain we ask: Does cultural change necessarily mean cultural loss? If my understanding of another person requires me to change a certain perspective of my religious outlook, then do I have to change everything? After all, when Adam and Eve ate the fruit of the forbidden tree, their knowledge was increased but they were exiled from the Garden of Eden. When my world view shifts as the result of meeting with others, when things I believed about other peoples and cultures no longer seem true, this change may be experienced as a loss; I may feel that something in my identity has been compromised.

In this domain we consider whether interaction with others who have different identities necessarily effects a positive change in one's own identity. Perhaps a distinction can be made here between boundaries and borders (Cornish et al., 2010). When we perceive the other's distinctiveness in a negative way, we erect a border between us and them; when we do not engage in negative stereotyping but instead observe and are aware of difference, then it becomes pertinent to just speak of boundaries: “Even when cultural difference and group identity are highly politicized in the wider society, by approaching the culture of the students forthrightly in the class room; such differences and identities can be depoliticized to a remarkable extent” (Banks & Banks, 2010, p. 47). We thus asked the following questions:

This domain utilizes the Privilege Identity Exploration (PIE) model (Watt, 2015). At the heart of this model is the understanding that privilege is one of the barriers to multicultural discourse and relationship, as it is inherently linked to a sense of guilt. Privilege is multidimensional; it appears in various configurations and is key to understanding majority-minority relations in the society.

Within this domain, students are asked about privileged groups on campus. Most people feel that if they acknowledge that they are part of a privileged class, then they are bad people. There is thus resistance to acknowledging privilege, and in our focus groups, the majority cultures in the class claimed that they are less privileged than the minority groups because they are not recipients of affirmative-action measures.

Having a privilege does not mean that you always feel that you are privileged. Michael Kimmel likens privilege to having the wind at one's back: it is invisible but nevertheless holds and propels you on course (Kimmel, 2012). Only when you turn your back do you sense the wind, because it is suddenly in your face. Peggy McIntosh also speaks about the invisibility of privilege when she writes: “I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was 'meant' to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless backpack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks” (McIntosh, 1989).

In this part of the questionnaire, therefore, we wanted to determine if and how multicultural work has succeeded in making privilege more visible. Of particular interest is the extent to which students of the majority culture were able to acknowledge their privileged status. We thus asked the following questions:

In the absence of a well-thought-out strategy, encouraging multicultural interaction might lead to a melting-pot ideal, where individuals feel that it is expected of them to give up their identity in favor of some kind of homogenous campus identity. Integrating all students, whatever their backgrounds, into a school's culture is a valid goal, even if this means that some students might need to temporarily forego certain aspects of their culture (which are currently inconsistent with the given school's culture). On the other hand assimilation, i.e., requiring that students give up all of their culture while on campus, is totally at odds with multicultural education. There will of course be gray areas concerning the extent to which a school's culture can accommodate a particular minority culture, and the level of accommodation will be dynamic and may vary from year to year. This domain seeks to determine if and how the difference is preserved and encouraged in the student's experience. We thus asked the following questions:

This domain is derived from the rise of the "Culturally Responsive Pedagogy" (CRP) approach (Vavrus, 2008). CRP is a relatively new term in multicultural education and focuses on curriculum development and teacher-training. CRP is a marked departure from the cultural deficiency model that emerged in the 1960s.

The cultural deficiency perspective assumes that children and youth who are culturally different from the mainstream society need an education that assimilates them into dominant norms and behaviors and away from the cultures of their families and communities. From this point of view, minority students are constructed as culturally disadvantaged by presumed deficits located within their cultural histories, beliefs and conduct. (Vavrus, 2008, p. 523).

Culturally responsive pedagogy is crucial to multicultural education which respects the integrity of every student's culture. Culturally responsive pedagogy “accommodates the dynamic mix of race, ethnicity, class, gender, region, religion and family that contributes to every student's cultural identity” (Wlodkowski & Ginsberg, 1995). CRP enhances the motivation of students to study and to engage with the material. CRP has also been found to help students develop a personal connection with course materials (Guido, 2017). There are four motivational conditions that facilitate CRP (Wlodkowski & Ginsburg, 1995):

A hallmark of CRP is that it includes cultural references and recognizes the importance of the students' cultural backgrounds in all aspects of learning (Ladson-Billings, 1995). The approach is meant to promote engagement, enrichment and achievement of the students by embracing a wealth of diversity, identifying and nurturing students' cultural strengths, and validating students' lived experiences and their place in the world (Villegas & Lucas, 2007). For investigating the extent to which multicultural educational work accorded with the principles of culturally responsive pedagogy, we looked to this domain in the questionnaire for students to answer the following questions:

Twenty focus groups were conducted, as part of crosssectional discussions with students from a variety of degree programs on the different campuses of Ono Academic College. About ten students attended each session. The main topic of conversation was cultural diversity, and the meetings were divided into two main stages: In the first phase of the meetings, students were asked about the significant issues they confronted concerning their multicultural experience on campus. Students were also asked to speak about their general opinion concerning studies on a multicultural campus. The topics addressed by the students in these sessions largely corresponded with the main topics in the research literature dealing with the multicultural campus learning experience.

Based on this correspondence between the theoretical literature and our focus groups, we formulated the domains that would make up the questionnaire at the center of this study. The domains chosen are: respect, privilege, loss and identity change, acceptance of the other, cultural inclusion, and CRT.

After the domains for the questionnaire were formulated, the second phase of the focus groups examined the six areas of cultural diversity. The purpose of the sessions at this stage was to flesh out each domain in the questionnaire. Concerning each domain, students were asked to bring up key experiences and concrete examples, and to discuss their views.

The sample consisted of 314 students in five campuses on Ono Academic College in Israel and the USA. The questionnaires were distributed within the framework of class sessions. Before answering the questionnaire, students were told that its objective was to gather information concerning their experiences on campus. It was also explained to them that the questionnaire is anonymous and that it would not be used beyond the purpose of this study. The average age of respondents was 32 years old (SD=10); 242 (77%) female, 150 (48%) first degree students and 164 (52%) second-degree students.

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS (2011) statistics program for Windows (Version 23.0). Statistical significance was set at p < .05 (two-sided). Descriptive statistics was used to determine the participants' characteristics.

The overall score is derived from the mean values of the six domains (after inversing negative items). Scores of each domain are derived from the means of the relevant items (after inversing negative items). In order to examine content and construct validity of the questionnaire, we conducted Cronbach's alpha internal consistency analysis, Pearson's correlations between the six domains and the overall score and confirmatory factor analysis (Extraction method: Principal Component Analysis Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

The ME-Q consists of 19 items on a Likert scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) representing 6 domains: Respect, Acceptance of others, Loss and change of identity, Privilege, Cultural accommodation and Culturally Responsive Teaching/Culturally Relevant Education. There are 3 questions in each domain, excepting “privilege” with 4 questions.

The ME-Q overall Cronbach's alpha revealed high level of internal consistency α=.752 and the overall variance explained is 69%. Fair to high levels of internal consistency were also found for each of the questionnaire's domains, Privilege α=.847 explaining 21% of the overall variance; Cultural accommodation α=.68 explaining 5% of the overall variance; Acceptance of others α=.779 explaining 8% of the overall variance; Respect α=.800 explaining 20% of the overall variance; Culturally responsive pedagogy α=.691 explaining 7% of the overall variance; Loss and change of identity α=.707 explaining 8% of the overall variance. All 6 domains reached eigen value >1 (Table 1).

Pearson correlational analyses conducted between the six questionnaire domains and the overall score resulted in medium to high associations (.409 ≤r ≤.697) (Table 2).

The questionnaire formulated in this paper provides schools with a tool that enables them to understand the multicultural aspects of their institution at both the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, a significant contribution of the questionnaire is the ability to identify different dimensions of the multicultural experience. Schools that use this questionnaire will be able to obtain information about the student experience, according to the categories (domains) formulated in the questionnaire. The schools will also be able to discern how these categories are influenced by such factors as lecturer attitude, classroom atmosphere, campus atmosphere, etc. Using this questionnaire will give schools a keen insight into the student experience and help to identify where intervention is needed in order to promote cultural diversity. At the macro level, the questionnaire formulated in this study allows institutions to gain a good understanding of the overall multicultural climate of the institution and to formulate clear objectives toward improving multicultural education. The questionnaire makes it possible to create six axes with a common vertex. Each axis reflects a different dimension of multiculturalism, according to the six categories (domains) formulated in this study-each judged on a Likert scale between 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). If we position the scale such that #1 is closest to the vertex and #5 furthest from it, connecting the points will inform us about the state of multicultural education at a given institution. The larger the circle produced from the connected points on the six axes, the better the level of multicultural education; the smaller the circle, the lower the level of multicultural education (Figure 1). Of course, there is no need to graph a perfect circle, since in different institutions different dimensions of multiculturalism will be expressed in different ways. An organization can postulate the geometric form that best reflects its desired goals, and then with the help of this questionnaire, it can both find out its current level of multicultural education and then (given an understanding of the dimensions that influence the level of multiculturalism in each domain) formulate a course of action to achieve its objectives.

Figure 1. Graphic Chart of the Questionnaire

Students in the focus groups referred to three different levels of contact within their institutions: with students, with lecturers and with administrators. The most meaningful connection with the “other” occurs between students, as students are together for long periods of time in the classroom; this connection is liable to be strengthened before or after class as well as during chance meetings on campus. Interactions with “other” lecturers and administrators, on the other hand, were reported as being more prone to students feeling discrimination and experiencing insensitive treatment.

The multicultural meeting creates a confrontation between different narratives. This confrontation can produce a change in the student's personal identity, and it can even lead to the loss of their cultural identity. Some students perceived the very presence of other students from another culture as confrontational, and this affected their participation and integration into their classes.

Students from privileged backgrounds varied in their self perception, with some seeing themselves as privileged and others pointing to affirmative action as discriminatory against themselves. Students are attuned to privilege in many areas; e.g., minority students reported feeling discriminated against when they are asked to study and express themselves in a language that is not their mother tongue and when their own religious and cultural holidays are not marked on their school's academic calendar.

Concerning the relevance of the material being studied, students reported that barriers are created when the discourse in class revolves around narratives that have no affinity and relevance to their own cultural world, and sometimes the student is unable to participate in the lesson optimally and absorb the material being taught. Conversely, many students felt that learning with a lecturer from their own culture contributes to their participation and integration into the lesson; that is, the very cultural identity between them and the lecturer gives them a sense of belonging, gives them confidence, and allows them to express themselves in the class and make their voices heard.

The assessment tool was found to be accurate and valid, and it thus may be reliably used to evaluate cultural diversity in an academic environment. Each of the domains was found to assess a unique aspect of cultural diversity. The findings, therefore, suggest that the questionnaire is a tool that can helpfully focus a school's efforts on the interventions required to enhance cultural diversity in an academic environment.

The impetus that gave rise to our research was the trend toward multicultural education in the academy. We believe, however, that the ME-Q has uses beyond higher education. Our assessment tool could be beneficial to all organizations that are interested in teaching and integrating different populations. Such an organization could be a type of school, such as a language school, but it could also have broader use, for example, in organizations that do job training. Anywhere that job training is offered, whether by high-tech companies seeking to update the skills of their employees, or by municipal agencies seeking to offer older citizens new career opportunities, if an organization wants to integrate a broad spectrum of people into its activities, people from different religious backgrounds; with different physical, mental and emotional needs; of a variety of ages, then it is in the interest of that organization to ask: how successful in fact are we at integrating people of different populations into our culture?

To what extent do the lecturers give preferential treatment to certain groups based on their culture?

To what extent are there privileged groups on campus?

To what extent do you feel that you belong to a group with fewer rights on campus?

To what extent do you feel that there is discrimination on campus based on cultural affiliation?

To what extent do you think that the campus manages to maintain your cultural identity and affiliation?

To what extent does the campus encourage cultural integration?

To what extent is cultural diversity an integral part of the studies on campus?

To what extent did learning in class with students from different cultures lead to a positive change in your attitude toward those different from you?

To what extent did studying with a lecturer from a different culture lead to a positive change in your attitude toward those different from you?

To what extent have studies on campus led to a positive change in your attitude toward those different from you?

To what extent do lecturers respect the culture to which you belong?

On campus, to what extent do you feel that your culture is respected?

To what extent was your learning experience in class accompanied by a sense of respect?

To what extent does learning with a lecturer from your culture contribute to your participation and integration in the class?

To what extent do the examples or stories presented in the lectures relate to your culture?

To what extent are the events or stories presented on tests or assignments related to your culture?

To what extent do the examples or stories presented in the lectures hurt your cultural identity?

To what extent does learning with students from different cultures make it more difficult for you to participate and integrate in class?

To what extent do you feel that the cultural language of the lecturers is distant (foreign) from your cultural language?