Figure 1. Distribution of Posts in Batsheva's Group Over its Years of Operation (correction to full years in Key)

"Shluvim" is a professional social network (hereinafter: PSN) in Israel. It serves as a space for educational professionals to collaborate and share knowledge, empower their professional development and receive emotional support. The authors aimed to characterize the groups operating in this network and the role played by the groups' leaders over the first four years of its operation, investigating motives for the groups' creation and the extent of group activity and created a model for policymakers and members of PSNs. Qualitative-phenomenological and quantitative data gathered from 16 semi-structured interviews, and a focus group indicated different rates of participation in the groups, distinguishing open and closed groups and identifying motives for their creation. The findings indicate the importance of social networking groups for members' personal and professional development, the importance of the group managers' activity, and reasons for a group's success or failure. Group members' were informed on the recommendations for successful group management.

Online activity has in recent years shifted from forums to Social Networks (hereinafter: SNs) (Sayan, 2016), which capture the largest proportion of Internet users' time throughout the world. From 82% of all user populations on the Internet, approximately 1.2 billion persons use the social networks. Weller (2007) discussed three levels of Internet communities (a) "online friends" - social network of acquaintances, (b) a network contributing to "community conferment", (c) "camaraderie" a network with long-term committed membership distinguished by Brown (2001). In contrast, educators usually work alone and therefore need a frame for constant exchange of knowledge, collaborative construction of knowledge and continuous professionalization and updating, consultation, and support. These supportive functions are essential for their professional development and some are already available in the virtual space. In the education field, social networks allow teachers to meet around a professional interest, to voice their opinions, receive encouragement for their daily tasks and share good advice in a non-threatening environment (Brown, 2001). The Mofe't Institute decided to establish the "Shluvim" PSN for teacher-educators and all other professionals dealing with education in Israel (shluvim, n.d.). The motivation for this move was to provide a platform for teachers, teacher-educators and educational leaders, to expose initiatives on a national and international level in the fields of education and teacher-training and to update educators on educational events relating to teaching and teacher-training. The "Shluvim" network is unique in Israel and connects educators in various education settings: schools, colleges, and universities. A pedagogic manager and technological consultant support the network members.

Online Learning Communities

SNs expand the time and location of learning (Greenhow, Robelia, & Hughes, 2009; Mazman & Usluel, 2010). They constitute a popular platform for discussion, interaction, communication and cooperation between their members (Boyd, 2014; John, 2012). They facilitate regular and egalitarian collaborative creation of knowledge, with the aim of dispersing the amassed knowledge. Characteristics of internet design, especially the ability to support non-centralized strong open communication, encourage collaboration and independent management of information in online communities (Brown, 2001; Weller, 2007). The community allows the user to join a group of experts and colleagues, to share information, to improve members' performances and to construct knowledge for future use (Lave &Wenger, 1991).

In online communities, members undertake a commitment to the group and indicate their willingness to cooperate (Shoop, 2009). There are clear rules with regard to behavior in the community, the quality of leadership and the types of organizations to which the community members are affiliated (Shoop, 2009). The literature indicates that it’s important for the group to define clear goals (Kim, 2000; McDermott, 1999) and that it can fulfill a genuine need by developing the learning of community members, creating links between a knowledge community and organizational processes; (Luan, Rico, Xie, & Zhang, 2016) note that excessive collective group identification actually represses external learning instead of promoting it. However, online knowledge communities usually act in an optimal manner, such that the structural and cultural components contribute to the creation of a rich texture of trust relations between members, with a sense of a common purpose, cooperation and reciprocity (Amin & Roberts, 2008; Hemmasi & Csanda, 2009).

Belonging to an online community and leaving it are usually a matter of free choice, the main reasons for joining being the desire to discuss and to find information on a common issue (Horrigan & Rainie, 2001; Ridings & Gefen, 2004). People share because they perceive themselves as having the ability to pass on materials and have a high sense of self-efficacy. Often people share with others because they believe that the giving and its reward are worthwhile in the present and the future. Thus, people who enjoy helping others will contribute more responses to SNs (Lin & Huang, 2013). In contrast, some members prefer to consume materials relevant to them without actively giving any contribution of their own (Lev- On & Hardin, 2008).

Online Learning

It seems that there are three essential components in an online learning community: a cognitive presence, an instructive presence and a social presence (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). A cognitive presence: This relates to components of the discussion which represent critical thinking including the expression of an opinion, understanding the process in depth by analyzing its different components, and also the ability of the participant to construct knowledge and create new meaning. An instructive presence: There are three dimensions to this concept: planning and organization of the teaching process, management and guidance of learning events and provision of direct instructions during the discussion while applying expertise in the field of knowledge. A social presence: This is defined as the learners' ability to express their personal and emotional experiences. While these three dimensions are easily achievable in face-to-face pedagogy, in an online environment characterized by a lack of non-verbal body language such as facial expressions, voice, and gestures, this is more difficult to achieve and greater effort is needed to attain a social presence (Rennie & Morrison, 2012). Tirado-Morueta, Maraver-Lopez, and Hernando- Gómez (2017) stress that social relationships are an essential component for group learning on the Internet, because they are the means by which the process is managed and controlled.

Another viewpoint was suggested by Salmon (2000, 2002) who listed five essential e- tivities in online courses that necessitate the instruction for the participants: (a) "access and motivation" and a goal for the performance of activities, (b) "socialization" based on interaction between learners/students/participants mainly through written messages, (c) "information exchange", (d) "knowledge construction", a synchronic process of construction and production of knowledge and (e) "development" – the expert stage.

Management of an Online Community

In workplace communities, staff who perceived their leaders as fair, demonstrated stronger group performances in the transition to an online space (Gruda, McCleskey, & Berrios, 2018). The online community manager is responsible for leading the virtual space in order to attain the community's predetermined goals (Collison, Elbaum, Haavind & Tinker, 2000). The manager is the host that enables and organizes the learning community. He is responsible for ensuring that the virtual space will be a meeting point where it is possible to process information, to construct new knowledge and to enable effective collaboration. They should stimulate motivation, create a pleasant atmosphere, allowing and providing assistance for the construction of knowledge, suggesting ways of operation and response, determining criteria for the conduct of discussion and ensuring that these will indeed be achieved.

The manager should affirm messages in line with the determined rules, enabling and strengthening connections between participants and suggesting conclusions. His role was essential for the success of the network, which was expressed by the quality of the online interaction, the level of collaboration and construction of knowledge (Gairín-Sallán, Rodríguez-Gómez, & Armengol-Asparó, 2010). Iriberri and Leroy (2009) noted that the manager is especially important in early stages of the community's development: the stage when the concept is consolidated, the establishment stage and the growth stage.

When the community begins to operate, the manager needs to perform very active management, enlisting members, creating different spaces for discussion and strengthening members' sense of community, safety, and privacy. The manager may also perform the important function of content management – supervising the community's agenda, assisting and encouraging discussions, moderating and preventing "eruption" of discussions, adapting the issue for discussion to suit community members' needs, preventing information overflow and taking care that discussions will be relevant to the subjects on the community's agenda (Kim, 2000; Gray, 2004).

Gattiker (2010) suggests several actions that group managers can take to maintain the survival of a group on the network: (a) provide a structure and focus for the group and clearly classify the posts, (b) provide support for and foster the participants. React to participants when they join the group, to publish and react to posts, (c) divide the management of the group with other participants in order to reduce the manager's burden and improve participants' feelings of involvement, (d) spread the posts over time and prevent crowding of posts in a particular period, so that there will be continuous interest and activity in the group. According to Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986), to acquire skills in all the required activities, the group manager needs to pass through the following five stages: novice, advanced beginner, competence, proficiency and expert. Progress through these stages is conducted hierarchically and at each stage important matters are learned. Online learning will be more meaningful when there is a supportive community with a professional manager/leader.

The research aimed to obtain a broad, more complete picture regarding the groups active on the "Shluvim" network and the contribution of the group managers to the regular and future running of the groups, following four years of the network's activity. The research questions were:

The research employed mixed quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis methods (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Keeves, 1988). This combination enabled the identification of the dynamics of statistical components over the development of the professional-SN, but also permitted deep investigation of the participants' experiences on the network through their communication with colleagues. Data based on one paradigm reinforced findings from the other paradigm and clarified different identified themes. Use of a single quantitative or qualitative paradigm would not have produced such a comprehensive picture.

16 active members including the initiator of the network, the pedagogic manager and the technological consultant, nine group managers and four active group members were selected to participate in the interviews.

Among the members, five members including the pedagogic manager lead 36 groups (between 4-10 groups each) constituting 24% of all the groups. The number of groups in which they are members range from 6 members in 3-5 groups, 3 members in 8-10 groups, 4 members in 14-20 groups to 3 members (all network leaders) in 23-47 groups.

The research was conducted online with ethical research rules. Each informant was asked for their informed consent and could cease their participation at will. They were promised confidentiality in any publication of the research findings.

Various qualitative research tools were employed:

A focus group – including four network members. Results of this pilot group constituted the basis for the research (Wisker, 2008).

Semi-structured in-depth interviews – 16 participants including the initiator of the network, the pedagogic manager and the technological consultant, nine group managers and four active group members (Seidman, 1998; Wisker, 2008; Yin, 2008).

Follow-up interviews - with ten group managers and the network's pedagogic manager.

Researcher's diary – in which the researchers recorded the different research stages, registering experiences from the network activities, interpretations, insights and understandings that emerged (Ely,Vinz, Downing, & Anzul, 2001).

In addition, analyses from Google Analytics data produced over four years of the network's operations was collected to obtain the usage profiles of the different network groups.

Qualitative data underwent content analysis (Atlas.ti 7.1) in order to create a richly detailed (thick) interpretative description (Geertz, 1973). Texts of materials uploaded on the network were read several times by two external judges and divided into repetitive "units of analysis" that were defined as categories (Denzin & Lincoln, 2017).

The findings represent four years' work of the "Shluvim" PSN, relating to (n=152) open or closed groups operating on the network with varying number of members and recorded visits. The groups have been active for different time periods and have different contents and characters. The term "posts" is used in the findings to describe cases in which a network member uploads new information or reacts to a previous message.

The network's (n=152) groups can be divided into open groups: 106 (70%) and closed groups: 46 (30%). Approximately a third (45 = 30%) were established to accompany academic courses, workshops and supplementary courses (especially at the Mofe"t Institute and Ministry of Education) and seven groups (4.6%) were established for particular activities: an event, seminar, conference or online meeting. Approximately half (74 constituting 49%) were set up to support work with technological tools and environments.

Open groups contents are open to all the network members and to lurkers (those who only observe materials and do not contribute their own knowledge) (Honeychurch, Bozkurt, Singh, & Koutropoulos, 2017), who are not members of the network. The decision to open the group's materials to all who are interested is motivated by the desire to receive broader and richer professional knowledge and to market it for the empowerment of members and to increase the number of group members.

I think that people in the group are open-minded regarding their group, they want to market it outside to other SNs or to invite suitable people in to enrich the group (Ran).

Closed groups allow group members to access their materials. This is determined by the desire of group members or the group initiator. Permission to join a closed group is given by the group manager.

The rate of visits in most closed groups is higher in comparison to the rate of visits to most open groups. The network's pedagogic manager regretted that all "this beauty and richness" does not reach all network members and those who are not members of the closed groups miss valuable materials. In practice, the network's members who are not members of a specific group on the network receive a rather modest picture of the scope, depth and quality of the groups' activities as explained by one of the group managers: "in closed groups the frequency [of visits] is far higher. But some of the people don't really want to be exposed to the network, so it is more comfortable for them to act in the closed groups and then they feel freer, no one sees them" (Ami). There are several reasons for choosing a closed group:

Members' Motives for Defining a Group as a Closed Group: The members of a group adhere to keeping a group closed because this framework grants them more intimacy and the ability to ask for personal professional advice. The group members are interested in maintaining information solely for themselves and do not want or feel any need to share it with other "strangers". As one group leader (hereinafter: GL) noted: "the considerations for closing a group are mainly serious. The moment that I said the group would be closed they were more willing to try it" (Batsheva). Sometimes this is due to a fear to open the group due to lack of confidence and lack of desire to deliberate as another GL explained, "Some of the people don't really want it to be open to the network, it is comfortable for them to work in closed groups. Then they feel freer, nobody can see them" (Ilan). Often, especially in learning groups where there is personal acquaintance in learning sessions between group members, the members asked to close the group. Sometimes the demand of one member created a reverberation among a larger audience in the group.

Managers' Motives for Defining a Group as a Closed Group: The GL can define the group as closed out of fear that visitors may not respect copyright and for fear that they may be exposed to legal claims because of the materials that are distributed. One of the closed group managers explained:

There are presentations whose contents haven't really meticulously examined to see if they are protected by rights. I prefer it to remain as closed material in a focused activity and not something that can emerge in a Google search and later I might be sued for that (Ran).

The Group's Logo and Name: The group's description on the network is significant. This is its shop window and may be the test of its attractiveness for new members. The visual representation of the group through its logo and name can create a sense of cohesion and pride for group members.

To summarize: There are various ways in which groups can define materials and the group can choose to be open or closed. There is variation in the times of activity and the duration of the group's activities. A few groups have a large number of members and visits in contrast to many groups with a small number of members.

3.1.1 The Group's Life Span

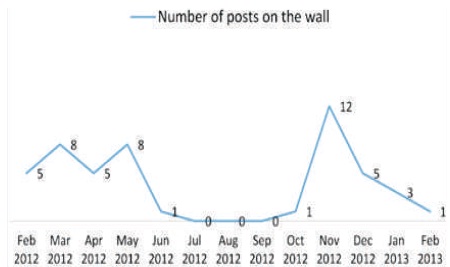

The period during which the group operates depends on the type of activity and the group's goals. Findings revealed three life span categories: (1) groups active over all four years of the network's operation. Intensity of the activities is influenced by school vacation dates and the main activity occurs during term time. (2) Groups active for a limited period, this is especially prevalent among groups accompanying a course/ supplementary studies that operate over the learning period. For example, in Batsheva's group the dates of posts correspond with the period of studies. Figure 1 shows the distribution by date of posts by the group manager and by members.

The data in Figure 1 indicate that most of the posts were published between February 2012 to June 2012 and between October 2012 until January 2013. These are periods when two supplementary courses operated.

Figure 1. Distribution of Posts in Batsheva's Group Over its Years of Operation (correction to full years in Key)

(3) Groups that are active for a short time, were established by an initiator interested to promote a particular subject but new members did not join, the group diminished and did not develop.

3.1.2 Groups that are More or Less "Attractive": Wavering Presence of Members and Changing Number of Visits to the Group

The Number of visits to the Group: indicates the network members' choice to expose themselves to the group and to the informative materials collected there. There were 10 groups (out of the 152 groups on the network) that leads to a range of number of visits (1428- 7188) and a range of number of members (26-127). Of these, seven groups were open groups and only one was closed, with regard to the number of visits, it appears that there is an outstanding number of members in the groups in 6 groups, all of which are open groups: there are thousands of visits and all of them (5 out of 6) apart from the "meaningful learning in education" group – a closed group with 74 members – had more than 100 members.

The Number of Members: 27 groups, constituting 18% of all the groups, are groups with more than 10 members, so that interaction can take place at a higher level. In contrast there are 125 groups, constituting 82% of all the groups, in which there are up to 10 members and the number of visits over the studied period was in total 999. This finding indicates that a large number of groups that were set up but found it difficult to attract many members and as a result the number of visits that they attracted was low and their activities were modest.

Analysis of the Activity in the Groups: It seems that many groups do not develop. In other words, the number of materials posted did not increase or no new members were added or both of these did not occur. One of the reasons for this is that "rich writing" groups require wider writing that deters many network members from joining them or actively participating in them: "I am concerned that groups which require rich and lengthy writing have a delayed take off, because people are afraid that their posts may not be expressed in a sufficiently intelligent and profound manner" (Ilan). Avoidance of writing may be due to different reasons: doubt regarding writing ability, the expression or contents may not be worthy, lack of writing skills, lack of time or lack of mental amenability.

There were 11 leading groups (constituting 7% of all groups) in the "Shluvim" network, which have the largest number of members and visits. Nine of these groups are open groups and just two are closed. The research findings indicate that it is possible to distinguish the groups by their materials and as either open or closed and according to the periods of their activity. It was also found that the logo and name of a group maintain members pride in the group. It was also found that there were few groups in which there were many members and a large number of visits (and there are also leading groups with large number of members but not many visits) compared with a lot of groups with very few members.

A network member who initiates the opening of a group naturally becomes the GL. The initiative to open new groups in the Shluvim network, 94 members (60% of 152 groups) each opened one group. 16 members opened more than one group (40% of all groups). In total, there were 100 of the 2,200 members of the network (5%), who initiated groups. The findings revealed several reasons for the opening of new groups: (1) To accompany a course or supplementary course. (2) To propose a new idea. (3) Leading an area of knowledge. (4) Self-branding. (5) The desire to express their leadership skills.

3.2.1 Group Managers' Five Main Types of Action The lone runner – The prominence of the group manager. The manager is almost the only active person in the group.

A bustle in the hive – The manager and the learning group members are active. The group manager stimulates members to participate, sometimes even in an artificial way and this creates a weave of members' activity intertwined with the manager's activity "continually creating interest, raising dilemmas to create conflicts. It's a lot of work. I succeeded in reducing dropout and determined a proportion of success" (Ami).

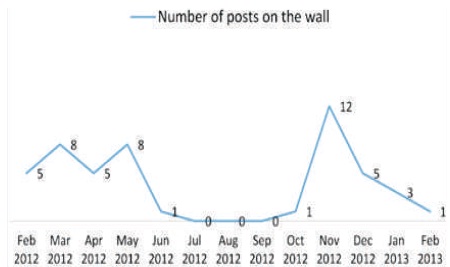

From the data shown in Figure 2 it is interesting to note two focal points when new members joined the group. Additionally, during the periods when there was massive joining of members there were also a larger number of posts by the group manager and the other members.

Figure 2. Profile of Batsheva's Group in which Both Group Manager and Members were Activewall over the Group's Activity Life

One member brings another – manager of an active group "linked" to "consumers who are not group members". In this phenomenon, the group served as the address to which the subordinates were referred in order to receive new information and knowledge. The group served as the channel for transmission of information to a larger audience.

New leader - The group manager is less active and one of the members receives or "takes" the leadership of the group. The group manager initiates and opens the group but its continued leadership is given to another member or one of the members assumes the instructional "presence" and becomes the leader guiding the group. The new leader needs several talents: ability to lead, manage and communicate with group members, defining boundaries and types of reaction. Moreover, they serve as "doorkeeper" to prevent the publication of hurtful reactions, needing personal and interpersonal skills.

Someone with an interest who knows how to manage communication with others, who doesn't reject the opinions of others, who knows how to encourage them and trigger and vitalize the discussion, who knows how to put people in their place when they write something hurtful and it's not always the group manager. These are personal and inter-personal skills and sometimes they are identified in one of the group members and he becomes the GL … I think that the group manager is a formal role but there is also an informal leader in the group (Ran).

The chameleon: An active group manager whose type of activity alters from time to time.

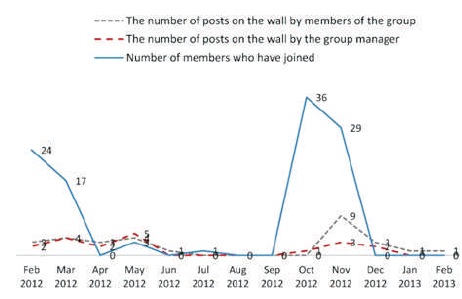

The data presented in Figure 3, shows that the type of manager's activity in the group underwent change as a result of the manager's trial and error. At first, the group's vision was to develop professional discussions and "conversations". However, when this did not occur, the group manager cleverly enlisted to lead the group. She initiated and reacted to discussion, but after a short time, when this effort failed to produce results, she adopted a new work style so that the group became a "platform" on which to share materials.

Figure 3. Comparison Between the Posts of the Group Manager and of the Group Members

But even to maintain the activity of the group in this form, the group manager was the main active person and continually made sure to inject new "oxygen" by uploading new materials in order to stimulate curiosity and interest. This increases members' motivation to share their own materials.

It can be concluded that there are a variety of reasons why people opened groups on the "Shluvim" network. One dominant reason was in order to lead a course, supplementary studies, a field of knowledge, a new idea and the desire to promote it. The research found that the group members can became group managers, and group managers whose role altered according to the circumstances and events.

The data indicate that there are 11 leading groups (7% of all groups) with a large number of members and visits. Nine are open groups and two are closed groups. In addition to the data, it emerged that there were 141 groups on the Shluvim network (93% of all groups) with a small number of members and a few groups had several dozen members. When there are few members, it is difficult to conduct discussion in the group, and the group's development and the formation of connections on the network are hindered. To develop an active group, necessitates regular activity by the group manager and members and when the number of members is small the level of activity is limited and there is less possibility of deepening discussion.

Three characteristics were found necessary for a group's success:

The peak of success and also personal satisfaction for the group manager was described with pride by Miki, who led activity in the group and guided professional use of materials that had been collected in the group in the context of a special initiative.

Beyond the fact that knowledge was created concerning learning contents appropriate for the pupil's age, a lot of professional knowledge was developed … one of the teachers told us how she created a small library for the teachers that they used for teaching and she printed all the collected materials in a book (Miki).

This story indicates the openness of the group manager who did not claim ownership of the materials or express any sense of "exploitation" by those who used the materials, many of which were in a private domain. On the contrary, the group manager continued to give backing to the group and understood her role as leading the group so that it could save time and much work for the teachers in creating teaching-learning materials.

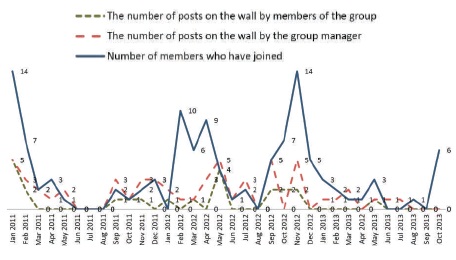

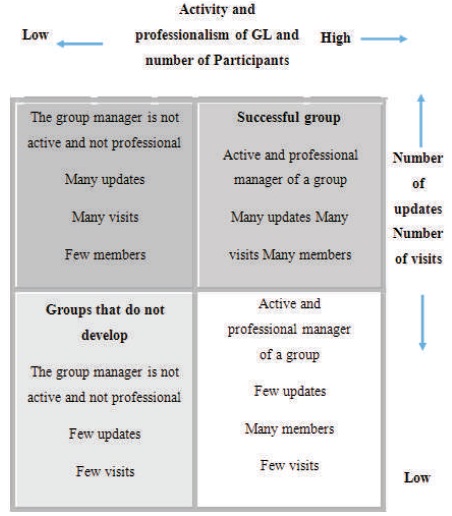

The data displayed in Figure 4 indicate that in a successful group, the group manager is active and professional and there are a large number of updates. In contrast, in groups that do not develop, the group manager is not active and there are few updates. Active, activating and containing– awarded title of successful group manager. The success of a group usually necessitates continuous work and a very high frequency of visits by the group manager. In the interviews with the group managers they stressed the importance of an immediate professional response for each of the members' posts.

Figure 4. A Successful Group Regarding the Activity and Professionalism of the GL and the Number of Updates and their Effect on the Number of Participants and the Number of Visits

I went into the group once every two days and when there was any activity then I would go in several times on the same day so that things would happen (Ran).

In addition to providing a response, it is important to maintain "respect" for members.

This aspect was highlighted in the interviews, when interviewees indicated that the words "we", and "we accept" should be used to increase the sense of a high cohesive social presence.

To summarize, the role of the group manager is very important, the manager determines and influences contents, the number of members and the manner in which they act in the present and the future.

Looking forward to the future, the research examined whether it was appropriate and worthwhile to be a group manager and whether there should be a training process for this role. The answers are not clear, there are skilled people who undertake this role without any prior training: "I did not learn to be a group manager, it came naturally to me" (Miki). But there are some who require prior training or some sort of mentoring and supervision to fill this complex role successfully.

The interviews revealed questions regarding the period of the group manager's tenure, should the manager's functioning in this post be limited in time? Or should they continue with the role over time as people continue with lifelong learning? An additional difficulty is that all the activities are voluntary and not rewarded financially or with academic credits. It was also found that in the groups where the group manager was not able to organize the information or thought that the technological tools of the network were unsuitable for this purpose, the group manager felt a strong sense of anger and disappointment and wanted to find a solution for the categorization of materials.

The "Shluvim" network constitutes the first innovative attempt to establish a PSN for educators in Israel. The contribution of the present study is that it helps to identify the factors that help groups to succeed more or less on the network and it attempts to point out solutions for the difficulties that were revealed, to ensure the future effective operation of the network.

It was found that the groups on a PSN can exist over time and contain a large number of members and also receive many visits, but this is only in cases where the group's activities are based on a robust foundation of an online community. Moreover, this foundation is formed when structural and cultural components contribute to the creation of a rich texture of trust relations between group members, a sense of a common purpose, cooperation and reciprocity as described by Amin and Roberts (2008) and Hemmasi and Csanda (2009).

Joining and leaving an online community are usually voluntary free choice acts, the main reason for joining being the desire to discuss a common issue and to gain access to information on it (Horrigan & Rainie, 2001; Ridings & Gefen, 2004). The unique nature of some of the groups which were tied to courses, was that they were initiated by the GL and people were "obliged" to become members. Here the motivation was not solely that of the participant but also of another entity that determined that this was a compulsory non-elective requirement. Moreover, in line with previous studies the present study revealed a prevalent phenomenon in the online communities: a significant proportion of the members prefer to consume relevant information from the group without contributing anything themselves (Lev-On & Hardin, 2008).

This creates the pattern of a three-level online community described by Brown (2001) that was found in most cases in the "Shluvim" network. Two of Brown's levels were found to exist: a SN of acquaintances, and a network that contributes to the discussion in a community of the original member, however the third level of "camaraderie" membership, was missing. Activity during the interface hours between work and leisure time, lack of financial or academic remuneration and lack of professional management by the group manager often led to members' lack of perseverance in the group's activity over time.

4.1.1 The Group Managers

The lack of a clear perception of the group manager's role in the SN, as a professional role that progresses in stages and perseveres over time, may "kill" the groups. Meaning that there will be no future continued development of the groups as an essential resource for members of the online professional community.

Those who led the groups on the Shluvim PSN were the initiators of the groups. Another possibility was that an active member of the group received the "appointment" of GL from the founding manager or as a result of his prolific activity in the group he undertook the role and received the support of the group, which perceived him as the leader in practice.

Group managers exhibited three types of presence in the group: instructive, cognitive and social (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000), although each group manager expressed these presences in either a consistent or changing manner.

The present study provided new meanings for the fivestage model of skill acquisition proposed by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986), in the transition from the stage of "novice" to the stage of expertise and suggests different stages that the GL undergoes. Most of the GLs acted as "novices", especially those who led the course groups, opened a group and asked everyone to join as a requirement for the course. At the second stage of "advanced beginner", some of the group managers saw that the group did not develop and tried another more flexible strategy. They answered and reacted to materials and information uploaded by members. Only a few GLs reached the third stage of "competence" when they realized the strength and power of the online environment. In the progress through these stages only a few individuals reached the penultimate stage of successful GLs. These were defined as "proficient" leaders with much experience who could understand which factors were most important for a particular situation and took decisions in a flexible manner based on the given situational factors. They were therefore proactive and also enabled and supported the actions of others. Only a very few reached the last stage defined as "expert", able to act intuitively, without relying on the rules and without thinking repeatedly about their actions. The expert "lives" the network and the group and acts intuitively.

It was concluded that the group manager should undergo all the stages of development, gradually identified by Dreyfus and Dreyfus, progressing and developing skills in a hierarchical manner, and at each stage the manager would learn the significance of the preceding and subsequent stages until they manage to master them. In this manner, the group manager would be seen as an acquired and learned professional role.

The Shluvim network group managers exhibited various administrative styles including the promotion of members' interaction, encouraging the creation of collaborative knowledge and constructing professional knowledge (Gairín-Sallán et al., 2010). But the extent of a group's success as measured by number of members and visits, is strongly influenced by the group manager's activity. When this phenomenon is examined in light of the model of Salmon (2000) it can be understood why some of the groups did not "take off" and remained with a small number of members or visits. All the group managers successfully completed the first stage of "access and motivation".

However, cracks began to appear at the second stage of "socialization" when the group managers did not always seem to understand that in their role as leaders and mediators they should tighten relations between members and create a social-learning environment. The GLs did however note that the third stage "information exchange" was the main purpose of their groups and the basis for initiating the group. However, the GLs' overlooking (sometimes out of lack of awareness) of the second stage led some groups to a standstill, lacking ability to progress and grow. "Fixation"- this stage did not allow many of the group managers to ascend to the next stage of "knowledge construction", a synchronic process of creation and construction of knowledge. At this stage activity actually stopped and no channel was created for further activity. Thus, only a very few groups reached the last stage of "development".

The contribution of the present study is that it provides increased understanding of the power and meaning of the network groups and those who lead them on aPSN for educators and this has implications for other PSNs serving different professions in Israel and abroad.

It is informative and valuable to understand the activity of group managers. In accordance with the group goals and aims and with the help of appropriate management, the group's work can be empowered and its contribution to members enlarged.

The role of the network manager and their interaction with group managers is obviously very important to gain optimal benefit from the leadership of groups in this distinctive PSN. Given the findings it would be valuable to develop the existing and similar networks with environmental development, following research on their activities, regarding the types of activities of their members, the position and role of the pedagogic manager and the leadership of the groups to successful operation.

In future planning the properties of the network and its members' desires or those of the group manager for differentiation should be considered in light of the increasing activity of global networks, as should the time of activity on the borderline between professional and private time. It was also found that the group manager, burdened by other matters often has difficulty to find time for group leadership, and the result is that many group have a short "life expectancy", and many groups ceased their activity. The question then remains whether they should continue to be visible or hidden.

Group activity on a PSN should be planned, innovative and professional and the group manager should be professional. The group manager should have a vision and ability to lead the community of learners for the short or long term according to the subjects discussed in the group and the members' needs. The group manager should ignore factors such as personal branding and try to lead the group to become a focus of attraction, learning and interest. Moreover, an essential condition for the continued activity of an enriching and helpful group is that the members should continually add new "oxygen" to the activities. The groups can succeed when they are positioned in a professional practical network and the GLs adapt the technological environment to the group's needs.