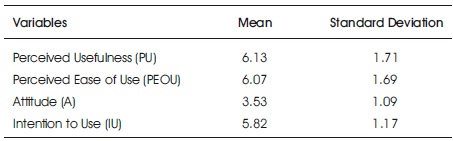

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables

Online learning has changed higher education, emerging as a primary source for delivering courses and programs to students. As online learning has grown, more non-traditional students have entered college, many for the first time. Consequently, many of these non-traditional are experiencing online learning, and the technologies that deliver them, for the first time. This quantitative research study developed and tested technology acceptance of online learning technologies using the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with variables perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, attitude, and intention to use. Findings from 40 valid responses in an online survey at Mountain Empire Community College (2016) USA, showed that perceived ease of use had a significant effect on perceived usefulness, which is consistent with TAM. Findings showed that perceived ease of use did have a significant effect on attitude. Further, perceived usefulness had a significant effect on attitude and attitude had a significant effect on intention to use, which is consistent with TAM.

The advent of online learning technologies has changed the way higher education institutions deliver instruction to students. Colleges, Universities, and Community Colleges are now offering online courses and entire online programs of study. According to Travers (2016), community colleges have been at the forefront of development and delivery of online learning to students. Community colleges provide a way for students that cannot afford to attend a larger college or university to get a quality education, or to get a lower cost start on their way to a four-year institution. A community college provides transferable programs in Arts and Science, Business, Technology, and Health Sciences while also providing programs in trades, such as industrial technology, welding, and electrical engineering. In rural areas, and small communities that many community colleges serve, the credential based programs and workforce programs are essential to many displaced workers. According to Pratt (2017), “to be sure, many students do not enroll with an associate's degree in mind: community colleges offer professional training and credentials, lower-cost academic basics for students who move on to four-year schools, and other opportunities for skill acquisition or intellectual exploration” (p. 36).

Online learning technologies allow colleges and universities to deliver instruction to students that may not be able to attend classes on-campus and students from other geographical locations. A Learning Management System (LMS) is the technology that delivers online courses to students through the Internet. An LMS provides “tools and functions like course management tools, online group chats and discussions, documents (lecture materials, homework, assignments, and more), power points, video clips uploading, grading and course evaluations to support teaching and learning” (Fathema, Shannon, & Ross, 2015). In conjunction with collaboration tools, such as Google Apps, Office 365, and Dropbox, an institution can provide a quality online learning environment. Online learning technologies have broadened and enhanced the learning opportunities colleges and universities can offer students.

It is essential to understand how online learning technologies impact non-traditional learner technology acceptance, as many non-traditional students are going back to school to complete a Bachelor's degree or pursue a Master's degree (Kuo & Belland, 2016). As Kuo and Belland (2016) noted, “Due to the advantages of online learning, such as convenience, flexibility, and financial benefits, many non-traditional students choose to take online courses to complete their Bachelor's or Master's degree” (p. 662). With many schools offering programs or courses online, understanding how technology acceptance differs between traditional and non-traditional students can help to improve student success and student retention, which can enable overall college success. This knowledge can also allow higher education institutions to design applications and programs that meet the needs of all students (Ellis, Pardo, & Han, 2016). The study in the succeeding sections is proposed to determine if there are signification differences between traditional and non-tradition learner technology acceptance with online learning management systems and collaboration tools.

With the opportunities that online learning technologies provide colleges and universities, how students accept these technologies can affect their success with online classes. The acceptance of students with the online learning environment, including online collaborative tools, can lead to overall educational success, and improve student retention (Thompson, Miller, & Franz, 2013). Kuo, Walker, Schroder, and Belland (2014) found that post-secondary students that accept online learning technology are more likely to be successful in their educational journey. The focus of this study was to examine the technology acceptance of online learning technologies of non-traditional students at a rural community college.

The study of technology acceptance of online learning technologies among non-traditional students in comparison to traditional students has remained a gap in research. There are multiple studies of technology acceptance of online learning for faculty; however, technology acceptance of online learning technologies among students has been lacking. For traditional students, the transition to learning online may be more comfortable than the transition for non-traditional students. The non-traditional student, in many cases, does not have the comfort level with online learning technology and therefore may have a harder time transitioning to online learning (Thompson et al., 2013). The purpose of this quantitative study was to gain insight and understanding into the technology acceptance of non-traditional students in comparison to traditional students.

An online learning system consists of computers, networks, storage, and electronic media. The design and implementation of an e-learning system are critical to helping ensure acceptance and student success. Understanding student attitudes toward e-learning systems can help information technology leaders and college administrators when evaluating e-learning systems for use. Dumciene, Saulius, and Capskas (2016) found in a study concerning student attitudes towards elearning that 40% of undergraduates and 42% of postgraduates treated e-learning as a method, of course, content delivery positively. According to Parkes, Stein, and Reading (2015), learning in an e-learning environment can be challenging. The Parkes et al. (2015) study focused on traditional students. The non-traditional student that likely has less exposure to online learning than the traditional student could find the e-learning system a more significant challenge.

The challenge for college and university information technology leaders and administrators is to implement an e-learning system that facilitates learning, acceptance, and success. For non-traditional students, learning online can be a challenge, and the design of the e-learning system can be a critical factor in their success. A critical factor in technology acceptance of e-learning systems is self-efficacy (Liaw, 2008). According to Chyung (2007), younger students have a higher self-efficacy in regards to e-learning. Therefore, students need to feel confident with the technology to have the best learning experience. Thompson et al. (2013) found that those students that were weak in technology self-efficacy where more likely to resist online. Deploying online learning systems that promote ease of use could be critical to the success of those students with low self-efficacy.

One way to deliver e-learning content to students is with the use of an LMS (Stantchev, Colomo-Palacios, Soto- Acosta, & Misra, 2014). The LMS has become very popular among universities as an e-learning system (Islam, 2016). The LMS is the backend application to deliver courses and course materials to students. According to Kasim and Khalid (2016), “An LMS is a web-based software package that is designed to plan, implement and evaluate learning, facilitate student interaction, give performance feedback, and manage student activities” (p. 59). Students can submit assignments directly to the LMS via the web interface and faculty to grade the assignments within the same LMS interface. According to Stantchev et al. (2014), “the use of LMS provides students and lecturers with a set of tools for improving the learning process and its management” (p. 612). The tools provided by an LMS has been a driving force behind online learning and is the reason higher education institutions have integrated LMS with other infrastructure systems (Rhode, Richter, Gowen, Miller, & Wills, 2017).

Several companies develop an LMS that higher education institutions can choose from when evaluating LMS for their institution. LMS providers, such as Moodle, ATutor, Blackboard, and Canvas are among the industry leaders (Kasim & Khalid, 2016). When compared, there are standard features among all the LMS providers, such as flexibility, ease of use, accessibility, and user-friendliness (Kasim & Khalid, 2016). However, the feature that is lacking is the ability to integrate with other systems (Kasim & Khalid, 2016). The higher education institution will need to evaluate each product and deploy the system that best meets the needs of the institution and promotes use (Rhode et al., 2017). According to Rhode et al. (2017), understanding the adoption and growth of LMS is essential for understanding technology acceptance and use of the system by both faculty and students.

A non-traditional student is an adult with student delayed college enrollment, continued education enrollment, did not complete high school, and are over the age of 24 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). According to Pratt (2017), a non-traditional student could have fuzzy academic skills and limited exposure to online learning. While many non-traditional, or adult learners, may have used computer technologies for work or pleasure, many have not used these tools for learning. There has been very little research into the acceptance of adult learners, or non-traditional students when using these technologies (Ke & Kwak, 2013a). Non-traditional students are the most substantial number of student enrolled in community colleges (Pratt, 2017). The average age of community college students is 29, and nearly half of the community college population is 25 or older (Pratt, 2017). Non-traditional students are students that typically have re-joined the education system after taking a break from learning after high school (Deschacht & Goeman, 2015).

Many non-traditional learners may have had little to experience with online learning (Deschacht & Goeman, 2015). Non-traditional students are older students that have not been in a formal educational setting for several years (Travers, 2016). Online learning requires a good grasp on Internet-related actions, and for those not comfortable with these actions, online education could be challenging (Kuo et al., 2014). With this in mind, to successfully plan and develop programs that efficiently use learning management systems and cloud-based collaboration tools, it is essential to understand the acceptance of non-traditional students when using these technologies for online learning.

For non-traditional students, the face-to-face interaction of their earlier academic experiences, and their day-today work lives is very interactive. These experiences create a learning style that is more suited to the interaction. Ke and Kwak (2013b) found non-traditional students favored face-to-face instruction and had lower acceptance with online learning. For online learning to be enhanced in a way that provides the interaction needed by non-traditional students, the design of the courses and technologies should create an environment that promotes, or simulates, this interaction (Ke & Kwak, 2013b). A combination of course design with media richness and communication technologies provided the environment non-traditional students needed to be successful (Ladyshewsky & Pettapiece, 2015).

Providing learning management systems with tools, such as collaboration tools, give the non-traditional student the tools for interaction with the instructor and other students. For example, discussion boards are a tool that nontraditional can utilize for interaction. Chyung (2007) found that when using discussion boards as part of an online course, non-traditional students posted more messages than the traditional students. The non-traditional student learns socially and needs the interaction with the instructor and other students (Capra, 2014). Designing the online learning environment, and courses, with this in mind can allow the non-traditional student to be successful (Xu & Jaggars, 2013).

User acceptance in information systems is vital for understanding how to design and implement those systems to ensure success. Research has linked two crucial outcomes to user technology acceptance: information systems success and continued use of an information system (Islam, 2016). According to Islam (2016), to find out how an end-user feels about a system or service is to analyze his or her acceptance of the system. For colleges and universities where many of their students enrolled in at least one online course, understanding acceptance with the online learning technologies can help guide information technology leaders and administrators to evaluate and design systems that enable technology acceptance among students.

Student technology acceptance is a principal factor to success in online courses (Cole, Shelley, & Swartz, 2014). According to Liaw (2008), understanding student attitudes towards e-learning is critical to improving elearning usage. While there are a large number of studies concerning technology acceptance among traditional students, there is little research on the acceptance of online learning technologies among non-traditional students. Colleges and universities are continually working to attract new students and retain current students. Technology acceptance of students with online learning systems determines their persistence in completing an online course (Tan & Shao, 2015). Therefore, in today's society where more non-traditional students are taking online courses (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016), understanding how to design the online learning technologies to meet the needs of both the traditional and non-traditional students is essential for higher education leaders.

When evaluating technology acceptance, there are critical success factors that can indicate the different levels of acceptance. According to Naveh, Tubin, and Pliskin (2012), critical success factors are content completeness, content accuracy, easy to navigate, easy to access, and course staff responsiveness. Evaluating these critical success factors can show students view the online learning system and can predict student success. According to Kuo et al. (2014), critical success factors are vital to evaluating student technology acceptance. Dalcher and Shine (2003) noted that demographic variables such as age are significant contributors to technology acceptance. Therefore, understanding the technology acceptance among students with online learning technologies is critical for designing online learning systems, as well as developing an institutional strategic plan for online learning.

The technologies that make up an online learning environment such as LMS and its tools, have evolved since their inception and many times change with new enhancements (Rhode et al., 2017). Research has shown that interaction between students and online learning technologies can influence learning outcomes and process (Gao & Wu, 2015). According to Gao and Wu (2015), past research has examined technology on measurable outcomes, such as academic performance, grades, and retention. Online learning has grown to a point where understanding the role of technology acceptance among the student population with online learning technologies is crucial for higher education institutions (Lamar, Samms-Brown, & Brown, 2016). By understanding how student accept the technologies that make up the online learning environment, institutions can develop and implement technologies that drive student academic success.

Technology acceptance is a measure of an individual intention to use technology (Fathema et al., 2015). TAM is a theoretical model created by Davis (1989) and is widely used to study technology acceptance. Researchers studying technology acceptance across various industries and disciplines (Fathema et al., 2015) have validated TAM. TAM has been widely utilized in technology acceptance research because its constructs have been validated and found to be highly reliable (Gao & Wu, 2015). Unlike other models, TAM has explained that individuals will accept technology system if they believe in the technology (Sondakh, 2017). Davis (1989) based TAM upon the theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Lamar et al., 2016). Using TRA as a base, Davis (1989) developed (TAM), which is now one of the most popular theoretical models for measuring technology acceptance (Lamar et al., 2016).

According to Wingo, Ivankova, and Moss (2017), in technology acceptance research, TAM has been found to be a robust and powerful predictive model. TAM has been empirically validated as a theoretical model for explaining end-user willingness to use new technologies (Wingo et al., 2017). Research has shown that TAM is the most influential, highly predictive, and widely used model for technologies adoption (Fathema et al., 2015). The use of TAM for research concerning technology acceptance has been validated by many researchers (Fador, 2014).

The key determinants of TAM are the constructs of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Past research has shown that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are predictors for attitude (Fador, 2014). According to Fador (2014), attitude and perceived usefulness are indicators of behavioral intention. The combined constructs of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, attitude, and behavioral intention can be applied to technology research in order to measure actual use of an information technology system. The application of TAM when examining and information technology system allows the researcher to understand how an end user's perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the systems impacts his/her attitude, which in turn impacts his/her behavioral intention to use the system.

TAM has been used to measure technology acceptance in higher education for many years. The perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the technology systems are contributors to student success (Fathema et al., 2015). However, there is very little research comparing the perceived usefulness and perceived use of technology among traditional and non-traditional students (Swanke & Zeman, 2015). When designing online learning technologies, the knowledge of how each group perceives the technology would be a critical factor in the design. Each group has different life experiences that could impact their perceived usefulness and ease of use of technology. Thus technology acceptance levels with online learning technologies may be different (Swanke & Zeman, 2015).

Technology acceptance in online learning can influence outcomes such as academic performance and retention. The same way technology acceptance findings in the corporate world have crucial significance for the organization and employees, so too does technology acceptance findings for higher education institutions and their faculty and students (Butler-Lamar et al., 2016). Past research has shown that technology acceptance among faculty and traditional students of higher education institutions is high, however there is little research on the technology acceptance of non-traditional students. With online learning being a critical component in higher education, understanding technology acceptance is beneficial for higher education institutions (Gao & Wu, 2015). Studying technology acceptance in higher education is critical for higher education institutions that consider online learning a fundamental part of their strategic plan (Wingo et al., 2017). Higher education institutions can implement better strategies for online learning programs if they better understand student technology acceptance of online learning technologies (Wingo et al., 2017). As the population of non-traditional students on college campuses and online programs continues to grow, understanding the technology acceptance of the non-traditional students with the online learning technologies is increasingly important.

The quantitative research methodology was selected for this research effort. The purpose of the effort was to examine technology acceptance of non-traditional students using online learning technologies. The quantitative methodology is selected for this effort because data analysis using statistical methodologies may prove enlightening and lead to the development of additional strategies to assist non-traditional online students. This research effort used quantitative data collected from students enrolled in online courses at Mountain Empire Community College (MECC) to determine technology acceptance of traditional and non-traditional students.

RQ1: As measured by TAM, does perceived ease of use have a positive effect on the perceived usefulness of online learning technologies in online courses at MECC?

RQ2: As measured by TAM, does perceived ease of use have a positive effect on user attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC?

RQ3: As measured by TAM, does perceived usefulness have a positive effect on attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC?

RQ4: As measured by TAM, does attitude have a positive effect on intention to use online learning technologies in online courses at MECC?

H1o . Perceived ease of use has a positive effect on perceived usefulness of online learning technologies in online courses at MECC.

H2o. Perceived ease of use has a positive effect on user attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC?

H3o. Perceived usefulness has a positive effect on attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC

H4o. Attitude has a positive effect on intention to use online 0 learning technologies in online courses at MECC.

2.3.1 Data Collection

The delivery method is a questionnaire created within the Zoho Survey tool. The students will receive an email providing survey information and a hyperlink to access the survey. The researcher will utilize Zoho survey because the college owns it and all students currently have access to the tool. The Zoho database will allow for a central collection point for all the data. The students will complete an online questionnaire using scales of the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Lamar et al., 2016). TAM scales help to measure satisfaction of technology among endusers (Edmunds, Thorpe, & Conole, 2012). The scales used for the study are perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, technical competencies, attitudes towards using, and intention of use.

2.3.2 Analysis

The results were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), to examine the TAM constructs. The SEM approach was used to develop a model of the relationships between the four factors in the study, Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Attitude (A), and Intention to Use (IU) the online learning technology. A path analysis was completed to measure the effect of each factor on the other factors as described in the hypotheses.

A total of four independent variables based on Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) were measured. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the TAM variables for non-traditional students. The means for the TAM variables of (PU) and (PEOU) for non-traditional students were 6.13 and 6.07 respectively with standard deviations of 1.71 and 1.69 respectively. The means for TAM variables (A) and (IU) for non-traditional students were 3.53 and 5.82 respectively with standard deviations of 1.09 and 1.17 respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables

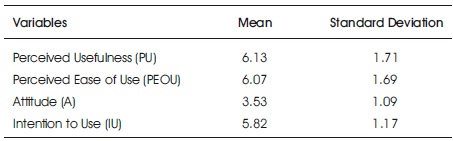

Table 2 shows the Cronbach's alphas for the TAM variables. The Cronbach's alphas for the TAM variables for non-traditional students range from 0.720 for attitude (A) to 0.957 for perceived ease of use (PEOU).

Table 2. Cronbach's Alphas for TAM Variables

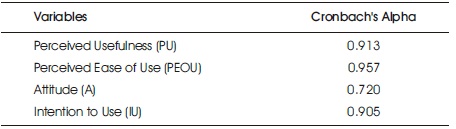

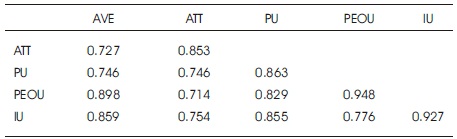

The correlation between the four factors was accessed to determine discriminate validity. Table 3 shows the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each factor and indicates a correlation between the questions for each factor. The (AVE) for each factor was above the minimum of 0.5. Thus, there are no issues with discriminant and convergent validity of the measures.

Table 3. Assessment of Discriminate Validity

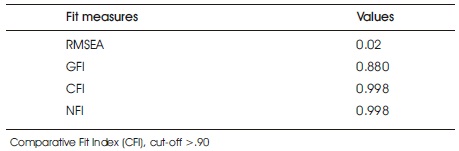

Four indices were used to access the model fit (1) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), (2) Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), (3) Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and (4) Comparative Fit Index (CFI). According to Lamar et al. (2016), due to the sensitivity of the chi-square test, using RMSEA is suggested as the principle goodness-of-fit index and that an RMSEA below 0.05 indicate a close fit. As Table 4 indicated, the RMSEA was 0.02. Thus the model is a close fit.

Table 4. Goodness of Fit Measures

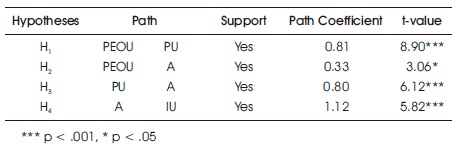

3.3.1 Hypothesis 1: Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness

The null hypothesis (H10) was: perceived ease of use has a positive effect on the perceived usefulness of online learning technologies in online courses at MECC. As Table 5 indicated, Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) demonstrated a significant influence on Perceived Usefulness (PU) (path = 0.81). Thus, based on the path analysis, the null hypothesis (H10) was supported.

3.3.2 Hypothesis 2: Perceived Ease of Use and Attitude

The null hypothesis (H20) was: perceived ease of use has a positive effect on user attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC. As shown in Table 5, Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) did not demonstrate a significant influence on attitude (A) toward online learning technologies (path = 0.33). Thus, based on the path analysis, the null hypothesis (H20) was not supported.

3.3.3 Hypothesis 3: Perceived Usefulness and Attitude

The null hypothesis (H30) was: perceived usefulness has a positive effect on attitude toward online learning technologies in online courses at MECC. As shown in Table 5, perceived usefulness demonstrated a significant influence on Attitude (A) toward online learning technologies (path = 0.80). Thus, based on the path analysis, the null hypothesis (H3o) was supported.

3.3.4 Hypothesis 4: Attitude and Intention to Use

The null hypothesis (H40) was: attitude has a positive effect on intention to use online learning technologies in online courses at MECC. As shown in Table 5, Attitude (A) demonstrated a significant influence on Intention to Use (IU) online learning technologies (path = 1.1). Thus, based on the path analysis, the null hypothesis (H40) was supported.

Table 5. Hypothesis Testing Results

This research study provides evidence for the technology acceptance model (TAM) for examining technology acceptance of online learning technologies. Furthermore, this research study provides evidence that technology acceptance of online learning technologies for non-traditional online students at a rural community college does influence technology use. The research objective, research questions one through four was to investigate the relationship of TAM constructs.

A total of 40 out of 980 invited participants responded to the online the survey hosted by Zoho survey with 100% completed. Demographic variables included age and experience with online learning technologies. The participants were 63.53% female and 36.47% male. Prior experience with online learning technologies indicated experience. Of the respondents, 51% had prior experience with online learning technologies while 49% had no prior experience with online learning technologies.

First, the reliability of the TAM scales determines that the instruments are free from error and are consistent. To measure reliability, the researcher measured the Cronbach's alpha for the independent variables. A Cronbach's alpha ranges from 0.0 to 1.0 with a minimum value of 0.70 for reliability (Gagnon, Stone, & Garst, 2017). As Table 2 indicated, the Cronbach's alphas for the TAM variables for all respondents all exceeded the 0.70 minimum value.

The survey instrument was designed on the four TAM scales; the perceived usefulness scale, perceived ease of use scale, attitude towards using scale, and the intention to use scale developed by Davis (1989) and validated in prior studies (Lamar et al., 2016; Fathema et al., 2015; Wingo et al., 2017). In this study, PEOU was investigated to determine if there was a positive effect on PU and (A), if PU had a positive effect on (A), and if (A) had a positive effect on IU. Findings showed that PEOU has a positive effect on PU and has a positive effect on (A). Findings also showed that PU has a positive effect on (A) and that (A) has a positive effect on IU. Thus, for this study, the construct relationships were significant as the TAM suggested.

Results from the path analysis showed that PEOU had a positive effect on PU (path = 0.81), and also had a positive effect on (A) (path = 0.33). Path analysis also showed the PU had a positive effect on (A) (path = 0.80). Similarly, path analysis showed that (A) had a positive effect on IU (path = 1.1) (Figure 1). Results indicated that attitude (A) is a strong predictor of intention to use (IU), as TAM suggested.

The research study has some limitations. The study was conducted at one of 23 community colleges in the Virginia Community College System (2017). Therefore, the results the study are restricted. To have a better understanding of the impact of TAM on non-traditional students, replication of the study at more institutions would help to understand the impact of TAM on non-traditional students. The study was also limited to one LMS. Future research should consider using external variables (computer self-efficacy, subjected norm, and system quality) on technology acceptances and technology usage on different LMS platforms (Blackboard, Canvas, Moodle, etc.).

As online learning has grown, community colleges have been at the forefront of development and delivery of online learning (Travers, 2016). The growth of online learning has also provided a way for working adults to earn an education. In many cases, online learning may be the only option for non-traditional students. According to Travers (2016), distance education may be the only hope for continuing education for non-traditional students. Providing online learning technologies that help these non-traditional students be successful should be a priority for higher education institutions (Gregory & Lampley, 2016).

Technology acceptance as defined by Davis (1989) explains the one's intention to use technology, which shapes the actual use of the technology. When technology acceptance is high, technology use is high. The technology acceptance model, when applied to community colleges, measure the technology acceptance of students currently enrolled in online courses. Community colleges have a diverse student enrollment with non-traditional students being a significant portion of that enrollment (Travers, 2016). Thus, examining technology acceptance of non-traditional students allows community colleges to deploy technology that increases technology acceptance of all students. The results of this research study effort support the findings of previous studies that TAM is a valid theoretical framework to examine technology acceptance (Lamar et al., 2016; Fathema et al., 2015; Wingo et al., 2017; Mallya & Lakshminarayanan, 2017).

The objective of this quantitative research study was to gain insight and understanding into technology acceptance of online learning technologies for non-traditional students at MECC. Thus, the study examined the TAM constructs based on the responses non-traditional students. TAM constructs results for non-traditional students were then evaluated to determine their significance on technology acceptance. The results of this study imply that further research will need to be conducted and expanded to understand technology acceptance of non-traditional online students. Future research should apply external constructs subject norm, experience, and computer self-efficacy to be measured along with the TAM constructs. By applying the external constructs, the research can gain a more finely-grained representation of TAM for predicting behavior toward using technology (Hubona & Whisenand, 1995).

MECC is like other community colleges where non-traditional enrollment is a large part of their enrollment. Low retention rates for non-traditional students is a primary challenge for MECC that must be explored and resolved. Recommendations for future research are: (a) expanding the study to other colleges in the Virginia Community College System, (b) conducting more research of technology acceptance for non-traditional students, (c) expanding the study to different online learning technologies. Strategies should be implemented to improve technology acceptance and eliminate the retention problem.

The study was conducted at just one small community college in the VCCS. Expanding the study to other community colleges in the VCCS, and larger colleges and universities, would provide more insight into technology acceptance of non-traditional students. While technology acceptance of non-traditional students was the focus of the research study, further research should be conducted to examine the difference in technology acceptance between traditional and non-traditional students. Understanding technology acceptance differences between these two diverse student populations would allow higher education institutions to effectively plan and implement technologies that drive student success and retention for the entire student population.