Figure 1. A Group is Dining at a SL Restaurant

This mixed-method study explored the changes in Turkish EFL learners' reported willingness to communicate and communication anxiety after conducting ten real-life tasks in a virtual world. Sixty-five university EFL learners (experimental = 30; control = 35) participated in this study. The participants were the first-year students of a foreign language teacher education program in Turkey. The intervention involved ten real-life tasks, one task each week. Data were collected via questionnaires, introspective interviews, weekly evaluation forms, observation, and focus-group and semi-structured interviews. Questionnaire data were analyzed through ANCOVA tests, and the qualitative data were subjected to content analysis. Overall results suggested that using a virtual world had a positive effect on the reported WTC and communication anxiety of participants who participated in the experiment compared to those who did not. Furthermore, the study suggests a model (NATURAL vs MATURAL) that explains the nature of communication in traditional classrooms and in a virtual world. These results suggest that incorporating virtual worlds in EFL context is worth the investment. Moreover, virtual worlds can become useful tools for learning and teaching of English because the interactions within the environment and learners' positive views on it are promising authentic and effective communication.

Foreign language learners are unable to use the target language in real life outside the classroom due to the fact that there is always a very limited opportunity for them to do this. Learners only practice the target language mainly in foreign language classrooms at a limited level. However, out-of-class activities are important as they afford real language use and play significant roles in sustaining language learners' motivation (Richards, 2015). At this point, computer-mediated communication is very significant because it helps to conduct real-class activities online (Garrison, 2009). Recently, Web 2.0 tools have been used to promote online discussion via computer-mediated communication (Solomon & Schrum, 2007). In addition, these tools have been used for various purposes, such as conducting real-life tasks (Richardson, 2006; Rosen & Nelson, 2008), teaching of the 21st century skills (Discipio, 2008; Goh & Kale, 2016; Greenhow & Askari, 2017) and cooperative and constructivist learning (Notari & Honegger, 2010).

Virtual Worlds (VWs) have recently aroused interest among educators as they provide constructivist and experiential educational tools (Wang, Song, Xia, & Yan, 2009). Online, publicly accessible VWs have been around since1995 and gained popularity in the mid-2000s. There are numerous VWs including Active Worlds, Croquet, Open Sim, Second Life, Quest Atlantis, and World of Warcraft. These various VWs were designed for different purposes, and different classifications have been suggested to describe them (de Freitas, 2008; Warburton, 2009). Warburton (2009) believes that “[t]he boundaries between these categories are soft and reflect the flexibility of some virtual worlds to provide more than one form of use” (p. 416). de Freitas (2008) considers Second Life and Active Worlds (AWs) to be social worlds that have public and general purposes.

In recent years, educational researchers have become interested in VWs and language development (e.g., Blasing, 2010; Dickey, 2005; Hislope, 2009). VWs have a great potential to promote language education as they allow users to practice a target language. Some earlier research conducted on VWs investigated the attitudes and perceptions of language learners (Balçıkanlı, 2012; Blasing, 2010; Cheong, 2010; Hislope, 2009; Huang, Rauch, & Liaw, 2010; Kruk, 2014; Liou, 2012; Wang et al., 2009; Wehner, Gump, & Downey, 2011), communication anxiety and shyness (Pfeil, Ang, & Zaphiris, 2009), interaction, online identity development and discourse patterns (Axelsson, Abelin, & Schroeder, 2003; Cooke- Plagwitz, 2008; Deutschmann, Panichi, & Molka- Danielsen, 2009; İstifçi, Lomidazde, & Demiray, 2011; Jamaludin, Chee, & Ho, 2009; Peterson, 2006; Shih & Yang, 2008; Stoerger, 2010), communication and avatar customization (e.g., Lee, Ahn, Kim, & Lim, 2006; Warburton, 2009), motivation creation and real life tasks (e.g., Sweeney et al., 2011), and social interaction in education (de Lucia, Francese, Passero, Tortora, 2009; Jamaludin et al., 2009).

Nunan (1999) believes that in traditional language classrooms, learners do not have positive views on speaking English because active communication in the curriculum/classroom is rare. It is found in the literature that many English teachers often do not teach their classes in English due to their low language proficiency. Lee (2002), for instance, showed that language teachers with self-perceived low proficiency avoid teaching communicative skills to their students. In conclusion, engaging language learners in real-life task is challenging in traditional classrooms. Utilising VWs may allow active communication in simulated environments.

Web 2.0 tools have been recently used to promote online discussion via computer-mediated communication (Solomon & Schrum, 2007). These tools also allow for “collaborative content building, dissemination, and categorization” of information (Sykes, Oskoz, & Thorne, 2008, p. 529), and have become the main communication tools among “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001). VWs, one of the frequently used Web 2.0 tools, offer a computer-simulated environment that simulates real or imaginary places. People can participate in learning communities and interact socially with others from around the world in VWs. Wagner and Ip (2009, p. 250) categorize VWs by considering their nature and purposes, and describe VWs as “immersive, three-dimensional (3D), multimedia, multi-person simulation environments, where each participant adopts an alter ego and interacts with the world in real time”. Residents of these environments can move throughout the world with ease by teleporting. All these features of VWs allow their users to conduct real-life tasks.

The communicative dimension of a language is at the center in a virtual world (Johnson, 2006). Using VWs with learners of English can be explored from the perspectives of constructivism, experiential and situated learning, and flow theory. Constructivism, a learning theory that contributes to the philosophy of knowledge with a new point of view, assumes that learning is constructed by interpreting new knowledge using prior knowledge (Kuiper & Volman, 2008). Experiential learning theory views experience at the center of learning, which allows learners to become involved in learning actively and take responsibility of their own learning. Learning by experience and in context also shows that learning takes place in the real environment. There are some implications of this theory for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) settings. Also, there is an inextricable link between constructivism and situated learning. According to Duffy and Jonassen (1992), “each experience with an idea-and the environment of which that idea is a part-becomes part of the meaning of that idea. The experience in which an idea is embedded is critical to the individual's understanding of and ability to use that idea” (p. 4). In situated learning, the key element is “participation”, which is described as “both the product and the process of learning” (Zuengler & Miller, 2006, p. 38). Flow theory asserts that learning environments need to be engaging in order to capture and keep learners' attention and to arouse their curiosity (Barab, Thomas, Dodge, Cartleaux, & Tuzun, 2005; Egbert, 2003). VWs can provide the opportunity for participants to interact with items including information, tools, and materials, as well as the opportunity to collaborate with others- both peers and instructors- by conducting real-life tasks. There are numerous researchers who found that VWs potentially afford experiential learning benefits (e.g., Chittaro & Ranon, 2007; Dalgarno & Lee, 2010; Jarmon, Traphagan, Mayrath, & Trivedi, 2009). A VW environment is also appropriate for situated learning as it enhances the learning efficacy and students can feel the sense of place (Bellotti, Berta, de Gloria, & Primavera, 2010). As far as the flow theory is concerned, a VW has the capability to encourage improvement in a variety of tasks at a rate favourable to users. For instance, users can choose, whether or not to partake in building exercises, depending on their skill level. Determining flow in a classroom setting is difficult because the difficulty and interactive nature of each task varies considerably per individual. However, it is reasonable to postulate that playfulness, a component of flow, can and does occur in the environment as users interact with one another and build. In short, VWs offer the potential to create a flow to help learners acquire foreign language learning.

A real-life task aligns well with the ultimate aim of foreign language instruction: to enable learners to use the target language in real-life successfully. Pedagogical tasks, on the other hand, form the basis of the classroom activity. Task-based Language Teaching (TBLT) has always attracted the attention of educators, SLA researchers, language teachers, and teacher trainers (van den Branden, 2006). Some of these studies investigated the effects of TBLT conducted in VWs on oral performance and interactions (Lan, Kan, Hsiao, Yang, & Chang, 2013); intercultural communicative competence and willingness to communicate (Jauregi & Canto, 2012); learner participation and engagement (Deutschmann et al., 2009); motivation, perceptions of anxiety, and self-confidence (Arslantas, 2012). Previous studies have found a close relationship between motivation and WTC of language learners (Bektas-Çetinkaya, 2007; Léger & Storch, 2009; MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei, & Noels, 1998; Peng, 2007; Wen & Clément, 2003).

When WTC is studied in second or foreign language communication, it can be seen that there exist some individual and situational variables, which influence a speaker's tendency to take part in the communication (MacIntyre et al., 1998). The WTC in these contexts was conceptualized both as a trait and a state level, which shows discrepancies in different situations. Some variables that act as a predictor of L2 WTC are motivation, perceived competence of L2, anxiety, teacher support, attitudes towards the international community, and their perceived linguistic self-confidence, online chat, integrative motivation, learners' perception of speaking activities in the EFL classroom, international posture, and students' attitudes toward the language (BektaşÇetinkaya, 2007; Freiermuth & Jarrell, 2006; Léger & Storch, 2009; MacIntyre, Baker, Clément, & Donovan, 2003; Peng, 2007; Wen & Clément, 2003; Yashima, Zenuk- Nishid, & Shimuzu, 2004). In this study, WTC is considered as “a readiness to enter into the discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using a L2” (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p. 547). In the literature, a close link was found between WTC and foreign language anxiety (e.g., Bektaş-Çetinkaya, 2007).

MacIntyre and Gardner (1991) point out that the foreign language learning process includes certain developmental stages in which learners experience different levels of foreign language learning anxiety. Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) is defined as “a distinct set of beliefs, perceptions, and feelings in response to foreign language learning in the classroom” (Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986, p. 130). MacIntyre (1999) regards FLA as the worry and negative emotional reaction provoked during learning or using a foreign language. MacIntyre and Gardner (1994) explain FLA as “the feeling of tension and apprehension specifically associated with second language learning contexts, including speaking, listening, and learning” (p. 284). Language anxiety is primarily based on foreign language speaking and conversation, and researchers regard communication anxiety as one of the most important anxiety types. Horwitz et al. (1986) claim that learners have negative reactions to foreign language learning because they feel anxious and insufficient in their foreign language communicative abilities. Besides FLA, speaking has its own specific characteristics that make EFL learners feel anxious (Horwitz et al., 1986). This type of anxiety may cause negative physical outcomes, such as dry mouth, sweating, weak knees, and nausea (Boyce, Alber- Morgan, & Riley, 2007).

Even though many studies have explored the factors that affect the WTC of foreign language learners both in different contexts (McCroskey & Baer, 1985; MacIntyre & Charos, 1996) and in Turkish context (Bektaş-Çetinkaya, 2005; Öz, 2014; Öz, Demirezen, & Pourfeiz, 2015), there is an empirical research gap in the literature on the tools to increase WTC. Considering that VWs offer venues and resources for foreign language learning outside of the classrooms (Chen, 2016; Arslantas, 2012), this study focused specifically on understanding the nature of communicating in a VW and its effects on the WTC and communication anxiety of EFL learners. Furthermore, their views on using SL were investigated. Hence, this study seeks answers to the following research questions:

The present study was conducted in the English Language Teaching (ELT) program of a state university in Turkey during the 2016-2017 academic year's spring semester. The program offers a four-year undergraduate study in English Language Teacher Education. Following the concurrent teacher education model, learners in this program learn basic language skills, such as lexicology, contextual grammar, reading, listening, speaking, and writing in the first year. They also take pedagogical courses such as introduction to education and educational psychology. From the third semester on, they begin to take field-specific content courses and pedagogical content courses, such as second language acquisition, linguistics, teaching language skills, teaching English to young learners, language testing, classroom management, material evaluation and preparation, and testing and evaluation. In the last year of the program, the students are required to take practicum.

The study was carried out with the first-year EFL students studying in the program mentioned above. The participants enrolled in a face-to-face Oral Communication II course in the second semester of the first year at the university. There were 118 EFL learners enrolled in this course. After a random selection of classes as control and experimental groups, the experimental group was introduced with SL. Then, the learners were asked to take part in this study voluntarily. After some withdrawals and excluding some others, the study was conducted with 65 of the enrolled students (Control group=35 and Experimental group=30). Some of the participants were excluded because they could not meet all the requirements of the course and the study. The general language proficiency levels of the participants were considered similar as they entered to the program with close scores of a national test. The computer skills of the participants were also explored via a background questionnaire and introspective interviews. It was found that the participants had no previous experience in VWs.

This study utilized both qualitative and quantitative data collection tools. The quantitative data were collected through questionnaires on WTC, motivation, and communication anxiety. Furthermore, a background survey was conducted to explore participants' demographic information. As for the qualitative part, introspective interviews, focus-group interviews, semi-structured interviews, weekly evaluation forms, and observation technique were utilized.

The WTC questionnaire, developed by McCroskey (1992), includes the communication contexts like public speaking, talking in meetings, group discussions, and interpersonal conversations, and receiver types like strangers, acquaintances, and friends. The participants were asked to choose frequencies ranging from 0% (I never communicate) to 100% (I always communicate). Communication anxiety was measured via a questionnaire that was used in several studies (e.g. Yashima, 2002) and includes the same contexts of WTC scale. This questionnaire requires participants to choose the percentage of anxiety in the communication contexts like public speaking, talking in meetings, group discussions, and interpersonal conversations, and receiver types like strangers, acquaintances, and friends. The participants were asked to choose a number between 0 (I never fell anxious while communicating) and 100 (I always feel anxious while communicating). The questionnaires were implemented to second and third year EFL learners before the study, and the reliability coefficients of the questionnaire were found as .89 and .86 respectively.

In addition to the questionnaires, this study utilized introspective, focus-group, and semi-structured interviews conducted in Turkish. Introspective interviews allowed the researchers to gather rich and detailed information about the participants as well. Focus-group interviews helped to improve the quality of the tasks, and semi-structured interviews helped to explore the opinions of the participants regarding their experiences in the VW.

The participants in the experimental group were trained for two weeks in which they were guided to edit profile, to move, to teleport, to offer teleport, and to change view angle of their avatars. All the sessions were carried out collaboratively, and the participants were to write weekly evaluation forms throughout the ten tasks. Some overall information was given about how they would conduct tasks and write in weekly evaluation forms. Tasks were conducted with groups of four to five participants undertaking their role-play in the virtual environment. Virtlantis, a virtual island in SL, was one of the islands selected as the research site (http://www.virtlantis.com/). In this island, the users could conduct real-life activities (i.e., a shopping mall, a music instrument shop, a cinema, a theatre). Screenshot software programs Bandicam and OBS were used to record task procedures. Each task was piloted before the real sessions, and accordingly, some notes were taken to improve the quality of the tasks. Another goal of the piloting was to test the suitability of SL to the participants by testing some samples of the real-life tasks. Figure 1 shows a screenshot from the 'Foods & Drinks' task.

Figure 1. A Group is Dining at a SL Restaurant

The tasks were adopted from some previous studies (Blake, 2000; Chen, 2016; Jee, 2010; Arslantas, 2012; Peterson, 2006; Smith, 2003), and participants and experts' opinions were gathered to finalize the tasks. At first 30 tasks were chosen. After asking opinions of the participants and four EFL teacher trainers, some tasks were merged or omitted. In the end, ten real-life tasks were chosen to be used in the study. The tasks were:

1) Orientation & Greetings,

2) Adventure & Travelling,

3) Foods,

4) Jobs,

5) Shopping & Clothing,

6) Art & Culture,

7) Sports-Games,

8) Music,

9) Health, and

10) Cinema & Theatre.

The tasks were generally conducted as role-plays as they would increase participation actively in learning activities, such as expressing their feelings, ideas, and arguments. Role-playing enhances learner participation and helps creating a dialogue between the learner and teacher and also between learner and learner (Bender, 2005), and it also fosters experiential learning (Wertsch, 1985).

The quantitative data were analyzed via ANCOVA. Shapiro-Wilk normality tests were conducted for all data sets, and it was found that all the data showed normal distribution, and thus parametric tests were conducted. Hence, in order to compare control and experimental groups, the study run ANCOVA tests. The assumptions of linearity, the normality of sampling distributions, homogeneity of variance and regression, and reliability of covariates were found satisfactory. Consequently, between subjects effects were calculated.

Qualitative data were analyzed via content analysis. According to Gass and Mackey (2000), qualitative data analysis steps, include transcription, coding, and description of data as well as data analysis. Similarly, Mackey and Gass (2012) emphasize that discovering patterns and developing well-grounded interpretations requires a systematic coding of the data. Patton (2014, p. 432) claims that the researcher is aware that there is no one “recipe” but there are “unique” ways of interpreting the data for each researcher. For anonymity purposes, SL usernames of the participants were used in the study. Anonymity was achieved because the participants were asked to register to SL with their usernames, but not with their real names before the study. After the interviews, their answers to the questions were member checked. Overall, the following stages summarize the data analysis of the study offered by Patton (2014) and Creswell (2009). For the analysis of the qualitative data, the researchers;

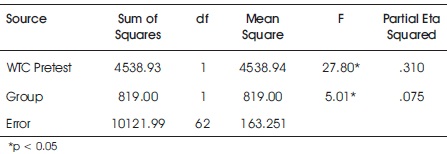

A one-way ANCOVA was conducted to answer the first research question that aimed at tracking the difference between control and the experimental groups regarding their WTC after the experiment. The post-test mean scores of WTC questionnaire were calculated as 51.84 for the control group and 59.32 for the experiment group. It can be seen from these mean scores that there is a difference and the mean score of the experimental group is higher than the control group. Table 1 shows the results of the ANCOVA on whether the difference between groups' WTC post-test mean scores is statistically significant or not.

Table 1. Analysis of Covariance Findings regarding WTC

As Table 1 shows, the findings revealed that using a VW had a statistically significant effect on adjusted WTC mean scores (F (1,62)=5.017, p<.05). In other words, controlling for the pre-test mean scores of WTC, there was a statistically significant difference between control and experimental groups in terms of adjusted WTC mean scores of the groups. As the difference was statistically significant, the effect size was also calculated. According to Cohen (1962), the effect size correlation means are as follows: <.10: trivial, 10 - .30: small to medium, .30 - .50, medium to large, >.50: large to very large. Hence, the analysis revealed a medium to large effect size (r=.417, adjusted r= .398).

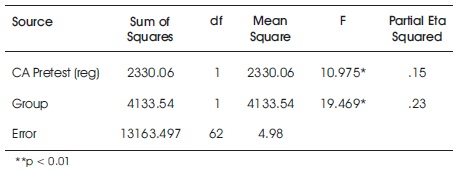

As for the second research question, the post-test communication anxiety questionnaire scores adjusted according to the pre-test results of the WTC scores showed that the final test mean scores of communication anxiety were calculated as 55.39 for the control group and 39.38 for the experiment group. The findings from ANCOVA (see Table 2) revealed that SL had a statistically significant effect on adjusted communication anxiety mean scores (F (1,62)=19.469, p<. 001). In other words, controlling for the participants' pre-test communication anxiety mean scores, there was a statistically significant difference between the post-test mean scores of control (M= 55.39, SD= 1.35) and experimental (M=39.38, SD=1.62) groups. The calculation of the effect size (r= .338, adjusted r= .316) was found to be medium to large (Cohen, 1962).

Table 2. Analysis of Covariance Findings on Communication Anxiety

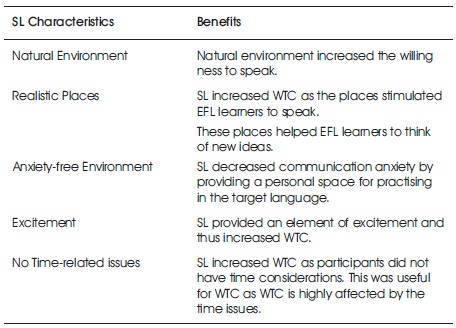

A detailed comparison of the WTC levels of participants before and after the experiment displays that the experiment led to increasing their WTC. As for the characteristics of SL that participants mention influencing their WTC, the themes in Table 3 emerged.

Table 3. SL Characteristics and Its Benefits for Increasing WTC

Most of the participants stated that they communicated in a natural environment, which, they believe, contributed to their WTC in English. The participants frequently stated that the islands and places in the SL were very realistic. They believe that communicating in such environments provided a sense of real-life purpose and thus increased their WTC in English. The students in the study also stated that they had the chance of communicating in an anxiety-free environment. As expressed in the extracts below, most of the participants feel peer and teacher-pressure, especially in face-to-face and crowded language classrooms. They said that communicating in this environment reduced their communication anxiety and thus they became more willing to communicate. Some representative quotes are as follows:

“It is nice to be in the original place where you can see objects around. It is more than being in a place where the real-life communication occurs. Also, as you see the objects, it helps you to find a topic to discuss” (Semi-structured interview, Adelina35).

“Interesting. Especially the environment is just like in real-life. The places are very realistic that you feel like you are in a real-world place. There used to be My-net chat, in which I was sitting in a café or at a bank to talk to other people, but here it is nice that the Avatar is communicating in a real world” (Semi-structured interview, Blackjacks).

“When I see a person, I cannot speak in the face. I am stuck. I think SL is much more comfortable because I talked through an avatar there and did not see the other people. At first, it was vague for me, but I got used to it later. I could speak in a relaxed atmosphere without being tense. Because nobody saw me while I was talking” (Semi-structured interview, Presedence life).

The anxiety-free environment also contributed to WTC as the participants took more risks and favoured spontaneous speaking instead of memorization. They believe that memorization results in mannered speech. In general, most of the participants viewed the SL experience as rewarding and interesting learning. They said that communicating in this environment aroused interest and stated that the tasks in which they were more interested in made them more willing to speak in English. In addition, this interesting and rewarding experience aroused some kind of excitement. As participants conducted the tasks whenever they wanted, they faced no time-related problems such as time limitation and feeling bad at some times. This feature of SL increased their WTC in English. More specifically, they stated that WTC is not stable for them, but changes in different situations and different times.

“This (SL) provides a more comfortable environment. As it is in the class, there is no need to worry about the professor and friends' reactions. I am a bit hesitant about taking the risk in the class. For instance, I speak with ready-made sentences that I memorized or thought before. This is because I cannot talk comfortably in front of everyone. Classroom talk is somehow mannered. However, I tried to take risks here without fear of making mistakes. This increased my WTC” (Semi-structured interview, Overdose07).

“Music task was fun for me. We went to a music instrument shop and conducted shopper shopkeeper role-play. There was a modern guitar around, and I could play it. I liked the place. It was good to go there, play the drums, play the guitar, and it was fun” (Semi-structured interview, Dippy42).

“It is nice to have the opportunity to talk whenever you want in a week and talking while sitting at home. Sometimes I am not in the mood for speaking, and sometimes I do not want to see any one. If I had to go to class every Monday, I would be less willing to speak. I may not feel well on Monday, for instance. Or I may not want to talk, but I can talk more when I want to talk” (Semi-structured interview, Shr96).

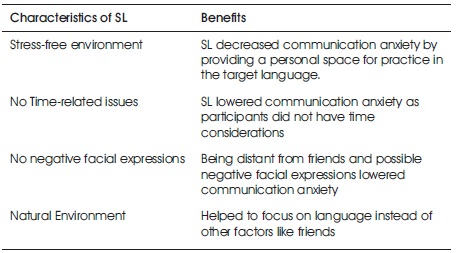

The analysis yielded significant themes that echoed throughout the content analysis of the characteristics of SL that participants mention influencing their anxiety in English. The excerpts below shed light on the findings in that students decreased their anxiety levels regarding the themes that were deductively related to codes emerged (Table 4). The themes were the stress-free environment, no time-related issues, no negative facial expressions, and natural environment.

Table 4. Characteristics of SL and its Benefits over Communication Anxiety

In terms of communication anxiety views, the extracts show that the SL experience proved to be beneficial since it enabled participants to talk in a stress-free environment. It can be concluded that SL helped them to decrease their anxiety levels. Most of the participants stated that speaking in SL is much easier and less anxiety-provoking when compared to a normal classroom. The participants believe that they were more comfortable as they did not have time limitations. According to the participants, SL provided flexibility in time and place. Another important reason for the easiness in SL was that it was not face-to-face and they did not see the negative facial expressions of their classmates. This is coded as no negative facial expressions. Not seeing other's facial expressions (e.g., raised eyebrows) was a relaxing factor for the participants. Some participants commented that being in a natural environment reminded them of real-life. It is stated that being lack of knowledge in L2 causes anxiety. If a student does not know enough words, s/he may stop communication and even avoid using the language. EFL learners in this study mentioned that being able to check dictionary reduced their anxiety. Here are some excerpts:

“Nobody sees you. You are drinking your tea and sitting comfortably. This naturally reduces anxiety. It is relaxing to talk in a relaxed atmosphere” (Semi-structured interview, Blackjacks).

“When you conduct these tasks in the classroom, you have to do them in a restricted time. This makes it difficult and unnatural. In SL, we talked about everything. There was no time limitation. However, when you are in the classroom, you have to listen to your friends more than you speak” (Semi-structured interview, Carpediem4245).

“I felt more comfortable as I did not see the mimics of my friends. Also, my friends could not see my face. When I make a mistake, my face turns to red. Moreover, when I feel nervous my friends display different mimics. This makes me uncomfortable in the classroom. In this environment, I feel more comfortable than in the classroom” (Semi-structured interview, Gmzsrt).

“For example, I talked at a restaurant in SL. So, when I speak at a restaurant in real-world, some words are easier to remember. This also reduces the anxiety level because you know that you already communicated in an environment like this. Hence, you feel more comfortable while talking to others” (Semi-structured interview, Overdose07).

The third research question explored the participants' overall views on SL. Separate themes were identified in relation to the issues associated with conducting real-life tasks in SL. These included positive views on SL, comparison of classroom and SL, and technological difficulties associated with SL. For the first category, almost all of the participants' comments (29 out of 30) showed positive views on SL. In general, most of them found the SL experience interesting and useful. The SL learning experience provided participants with a chance to communicate with their friends from their houses or dormitories. The interviewees used mainly these adjectives: “natural”, “adventurous”, “attractive”, “liberating”, “provocative”, “security”, “constructive”, “experiential”, “collaborative”, “interactive”, “unlimited”, “time-free”, and “realistic.” The participants believe that the characteristics of SL contributed to their speaking skills and communicative competence. The participants believe that no giggles or raised eyebrows allow them to communicate in a stress-free environment, which was useful for better communication. According to the participants, SL can provide a sense of security by providing a personal space for practising in L2. As another advantage of SL, they mentioned that this environment provided an element of excitement. Last, they also mentioned that SL fostered real-life applications of experiential learning. They believe that SL with ten real-life tasks provided a sense of responsibility. Some of the examples are,

“SL is very realistic and interesting. I think SL helped me to think in English and try to speak more and more. It also helped me to practice and share ideas with others. This practising improved my speaking skills” (Semi-structured interview, Killinghumar).

“The class sometimes does not respect. For example, when you pronounce something wrong, they give strange reactions to the class; such as mimics and weird movements” (Semi-structured interview, Carpediem 4245).

“When communicating in SL, I feel myself like in there in my real life, and I am feeling like in real life. It (SL) is realistic” (Weekly evaluation form, Adelina35).

“We met at a horse farm and rode horses. It was like in real life and therefore it made me like I really did sports” (Weekly Evaluation Form, Mehmetbey).

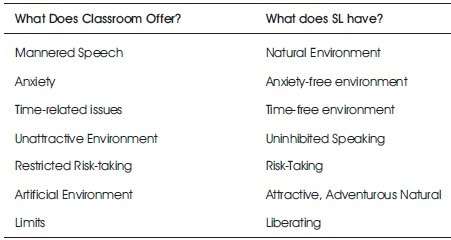

When all the data analyzed and the participants' comparisons of SL and classroom were considered, the following themes emerged. Concerning the disadvantages of classroom perspective, this analysis can be discussed under a model named MATURAL (Mannered Speech, Anxiety, Time-related issues, Unattractive Environment, Restricted, Artificial, and Limits). In other words, EFL learners believe that if they had conducted ten real-life tasks in SL, they would have memorized their parts and that would have resulted in “mannered speech”, they would have felt more “anxious”, they would have had “time-related issues”, they would have communicated in an “unattractive environment” and an “artificial environment”, they would have communicated by “taking no risks”, and they would have encountered many “limits.” When it is considered from the advantages of SL, the NATURAL model (Natural, Anxiety-free environment, Time-free environment, Uninhibited speaking, Risk Taking, Attractive & Adventurous places, Liberating) emerges. In other words, the participants who conducted tasks in SL stated that they conducted the tasks in a “natural”, “anxiety-free”, “time-free”, “attractive”, and “liberating” environment. Moreover, the environment allowed them to “take more risks” and “uninhibited speaking.” More specifically, the themes emerged as an advantage of SL have their counterparts. The pair of contradicting themes are “mannered speech” vs. “uninhibited speaking”, “anxiety” vs. “anxiety-free”, “time-related issues” vs. “time-free”, “unattractive” vs. “attractive”, “restricted risk-taking” vs. “risk-taking”, “artificial environment ” vs. “natural environment ”, and “limits” vs. “liberating”. Both dimensions of the model are illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5. The Matural vs. Natural Model

The participants stated that they had a chance to communicate in a non-threatening nature of SL. Twenty-six of the participants claimed that they would have memorized their roles if they had conducted those ten tasks in the classroom. Consequently, they would have communicated in a mannered way. One opinion was:

“If I was in the class, most probably I was going to memorize my parts in the roles. In this respect the class is different. In real life, we do not talk to people with the sentences we memorize. There was no need for something like that in this environment. This is because all eyes were not on us. Our friends could not see us. In this respect, this environment is more suitable for real life. In addition, talking spontaneously rather than speaking in a mannered way, improved my competence to speak” (Semi-structured interview, Presedence life).

Another major difference between the classroom and SL was about the level of anxiety that they experienced. Almost all of the interviewers stated that they communicated in a less anxious state. They believe that SL created a safe and pleasant environment for them to speak as they experienced communicating without seeing their faces. Although they knew whom they were speaking to, this created some kind of anonymity. In other words, not seeing their friends' faces reduced their anxiety. One comment is as follows,

“Nobody sees you. You are sitting at your home and drinking your coffee or tea. This is very good for feeling better. If I am very nervous and anxious, I cannot produce good and correct sentences, and this does not help my speaking abilities” (Semi-structured interview, Blackjack).

As participants conducted the tasks whenever they wanted, they faced no time-related problems such as time limitation. When compared to the classroom, this feature of SL was very beneficial for them. For instance, this feature of SL increased their WTC and motivation in English. More specifically, it can be concluded that participants do not view WTC as stable. It can change in different situations and different times. This state nature of WTC was suitable for communicating in an environment in which the participants were given the opportunity to communicate whenever they wanted in a week. Furthermore, they felt less anxious when they were able to choose the time of communication. They stated that being in the mood is very important for speaking. A representative answer was,

“It is very nice that it is comfortable at home and when we want it to be. The class is a problem in terms of time. To be clear, you sit in class for three hours. There is noise. However, I am comfortable here. I really do not like sitting for three hours. It is not natural to talk at a certain hour every week” (Semi-structured interview, Shr96).

The participants stated in the inter views that communicating in the classroom is not attractive after experiencing an environment like SL. A representative thought is,

“Speaking in this environment is more interesting than in the classroom. In the classroom, you need to use your imagination to talk about something. Second Life, on the other hand, provides you with a real-life seating. For example, you can see the musical instruments and even play them. Being in a musical instrument shop, playing and speaking at the same time makes the conversation more realistic and attractive. In the classroom, on the other hand, you need to imagine and speak at the same time. So, I find the classroom environment unattractive”. (Semi-structured interview, Betty-house).

Participants are more likely to take risks and communicate more easily in SL. They stated that they could speak as they wished. They did not consider the others' negative evaluations of themselves. They believe that classroom restricts their risk-taking such as trying to compose complex and long sentences as they feel peer and teacher pressure.

“When you make a mistake while talking to a person whose native language is English, they just enjoy it. It is same for us. If a person who speaks Turkish as a foreign language makes a mistake we just enjoy it. However, our classmates are very harsh against mistakes. This is demotivating for me. That is why I try to be very simple in the class. In SL, on the other hand, I spoke how I want. I tried to use very different types of sentences” (Semi-structured interview, Gmzsert).

Most of the participants stated that they found the classroom environment artificial, which was not very beneficial for improving natural speech. However, they believe that SL provided them with a natural environment to communicate. A representative quote is,

“SL is very comfortable. We conducted our tasks in the evening. I drank my coffee while speaking. We gave breaks whenever we wanted. While doing music task, for instance, we were listening to songs and background music facilitated our speaking. It was more natural than the classroom” (Semi-structured interview, Carpediem 4245).

Other than time-related issues, the participants mentioned a variety of limits of the classroom. They regarded SL liberating. One participant believes,

“The classroom is limited regarding materials that help to speak. For instance, I confuse the meanings of vertical and horizontal. Speaking in the classroom, I could never found a solution. However, in this environment, you can easily match the word you use and the picture. That is very helpful” (Semi-structured interview, Dippy42).

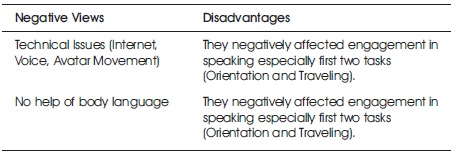

The disliked points of SL can be categorized under technical issues and some other disadvantages (see Table 6), some of which were discussed under the comparison of SL and the classroom.

Table 6. Some Difficulties with SL and its Disadvantages

The participants reported a few technical issues with regard to accessing and operating within SL, which they believe affected the process in a bad way. The problems are mainly about Internet access speed and microphone problems. Some participants complained about the problems with using the microphone in SL. Some examples are as follows,

“Everything is good in SL. The only problem we have here is technical problems. This is inevitably affecting us” (Weekly evaluation form, Mehmetbey).

“Internet problems affected our speaking. While talking to each other, one of us could not hear, and one of us could not use his/her microphone properly. This affected us in a bad way” (Semi-structured interview, Obliviate).

Some participants complained about the movements of their avatars. The most common problem was avatar freezing and losing control of the avatar. Other than the technical issues, the participants mentioned some other disadvantages of the virtual world. One disadvantage was related to body language. One of the participants stated that being unable to utilize body language was a negative side of the SL. She believes that using and following others' body language is very important for their communication. Moreover, she also said that they would have learned from other groups' tasks in the classroom. Although most of the participants viewed SL as a social network, a few students experienced loneliness in this environment. For instance, one participant looked at the VW as an environment that addresses isolated people. He felt that SL was only a game and that the avatars do not represent reality. Some complaints are as follows,

“My avatar acted very weirdly while playing tennis. You can even sit on a basketball hoop” (Weekly evaluation form, Dippy42).

“This place is really intriguing, but I think classroom setting is still better than SL. I mean, it is very important to be able to use body language for communication. Eye contact is also crucial. You cannot do these in SL. Also, I could not watch the other groups. If I were in the classroom, I would learn from other groups. We tried to improve task procedure with your and another group's advice. However, we could not observe the other groups” (Semi-structured interview, Mulan).

“It is exciting to communicate in this environment. Moreover, the places are very realistic. However, in the long run, I think it is for a social people who cannot speak in the face-to-face environments” (Semistructured interview, Rcp).

The findings regarding the first and second research question indicated that there was a statistically significant difference between control and experimental group. Hence, it was concluded that SL was found to have a significant effect on WTC and communication anxiety of EFL learners in the present study. In other words, participants' WTC increased and communication anxiety decreased at a statistically significant level after using SL. This is confirmed by the qualitative results as well. The content analysis of the data showed that the characteristics of SL increased the WTC and lowered the anxiety of the participants. The third research question was qualitative in nature, which explored the views of the participants on the use of SL for real-life tasks. Some different themes were identified regarding the issues associated with conducting real-life tasks within SL, which included positive views on SL, comparison of classroom and SL, and technological difficulties associated with SL. The major themes that appeared in positive views on SL were perceived competence in L2, L2 anxiety, security, excitement, and responsibility. As for the comparison of classroom and SL, the MATURAL vs. the NATURAL model emerged.

Findings indicate that VWs enable EFL learners to gain WTC in English, which is in line with the literature (e.g., Jauregi & Canto, 2012). The participants found the virtual environment natural to communicate, and this increased their willingness to speak. The realistic places of the environment were another factor that affected WTC. The nature of the places makes it necessary to mention situated learning, which occurs successfully when the language learning tasks are goal oriented, situated, interactive, and authentic. According to Felix (2002, p. 3), in situated learning learners are “active constructors of knowledge who bring their own needs, strategies and styles to learning, and skills and knowledge are best acquired within realistic contexts and authentic settings, where students are engaged in experiential learning tasks”. Results of this study also showed that another source of the increase in WTC was the fact that SL provided an environment in which the participants could take more risks than in a classroom. Being involved in a virtual world and conducting tasks in this environment improved their WTC in English.

After the experiment, participants' views on their WTC changed. They reported that being in an environment in which they felt like they were in an English street and speaking in the real setting, helped them to increase their WTC, communicate in a realistic environment, and communicate for real purposes. This is also related to the ecological perspective of language learning in SL. Panichi, Deutschmann, and Molka-Danielsen (2010) discuss participation and language learning in VWs by introducing an ecological model. This perspective posits that the user of a virtual environment interacts not only with the environment, but becomes part of the environment. It sees systems as open, complex, and adaptive comprising elements, which are both dynamic and interdependent. For this perspective, all learning is contextualized and situated in an environment. It sees the student both as a part of the environment and one of the factors in determining subject matter. This model is also in line with the sociocultural theory as it gives significance to meaningful participation in human events and meaning construction.

It can be concluded from the findings that SL has a potential impact on decreasing participants' communication anxiety in English. The major themes as the characteristics of SL decreasing communication anxiety were: stress-free environment, no time-related issues, no negative facial expressions, and natural environment. The results of this study showed that SL has the potential to decrease the anxiety of EFL learners which is in line with findings of the some previous studies (Balçıkanlı, 2012; Cooke-Plagwitz, 2008; Couto, 2010; Deutschmann et al., 2009; Dickey, 2005; Jarmon et al., 2009; Arslantas, 2012; Pfeil et al., 2009; Wehner et al., 2011). The findings of this present study illustrate that the anxiety felt in the classroom is debilitative in nature. The anxiety-free nature of SL mainly stems from the fact that their classmates did not see them while speaking. FLA is regarded as the negative emotions towards the learning or using a target language (MacIntyre, 1999). From this perspective, it can be deduced that SL is also a way of reducing foreign language anxiety. There were some characteristics of the SL environment that provided advantages for EFL learners. For example, SL allowed them to connect from their home or dormitory with just one click while sitting and this created an anxiety-free environment. It can be deduced that SL is also a way of reducing FLA anxiety. The decrease in the anxiety levels was also useful for the increase in the WTC. This is also confirmed by some previous research studies. Hashimoto (2002), for instance, investigated whether motivation and WTC could predict the frequency of communication in the language classrooms. The findings yielded that perceived competence and language anxiety were found to be significantly related to WTC. Horwitz et al. (1986) mentioned three components of FLA: communication apprehension (CA), test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation. According to Aydın (2008), language learners' fear of negative evaluation is a critical issue in EFL learning contexts. For example, involving in evaluative situations may cause a fear of negative evaluation. Job interviews can be given as an example to fear of negative evaluation. As the participants of this study experienced this kind of real-life tasks, their fear of negative evaluation was also decreased via the use of the virtual environment.

When SL and classroom environment were compared and the qualitative data were analyzed in detail, the NATURAL vs. MATURAL model emerged. From the classroom perspective, this analysis revealed the dimension of the model named MATURAL (Mannered Speech, Anxiety, Time-related issues, Unattractive Environment, Restricted risk-taking, Artificial environment, and Limits). When the advantages of the SL are considered the NATURAL dimension (Natural environment, Attractive Environment, Time-free environment, Risk-taking, Liberating) emerges. In further research, this model can be checked via quantitative methods under the model studies that explain WTC, motivation, and communication anxiety in English. While the NATURAL dimension explains the nature of communication in SL, the MATURAL dimension highlights the shortcomings of the classroom for real-life tasks in EFL classrooms. The NATURAL vs. the MATURAL model also shed light on the issues on having a chance to communicate and willingness to communicate in EFL contexts. Previous research showed that Turkish learners need more stress-free environments to participate orally (Jackson, 2002; Öz, 2014). The participants of this study repeatedly mentioned that they find the classroom environment artificial to communicate in the target language. This was highlighted with “Artificial Environment” in the MATURAL model and with “Natural Environment” in the NATURAL environment. The findings suggest that Turkish learners have no problems with having a chance to communicate, but a willingness to communicate. Together with the “Artifical Environment”, the MATURAL model explains the other factors that make Turkish EFL learners unwilling to communicate.

One of the important findings from this study was that conducting real-life tasks in SL affected EFL learners' WTC and communication anxiety. Another major finding was the NATURAL vs. the MATURAL model that explains the nature of communication in SL and in the traditional classrooms. The MATURAL dimension of the model also explains the avoidance of speaking in regular language classrooms. Even though this research did not aim to discover the effects of using tasks on WTC, motivation, and communication anxiety, an implication of the research is the contribution of task-based learning. Tasks were successful in involving participants in active participation which was reflected in the transcripts. This research showed that EFL learners could practice communication in SL without feeling negative affective factors. It also shows that VWs can become useful tools for learning and teaching of English because the interactions within the environment and EFL learners' positive views on it are promising authentic and effective communication.

Another finding of the study was that EFL learners participated in the tasks. The tasks were useful in eliciting active participation, which was also seen in the interviews and researchers' observation. First of all, as SL increased participants' WTC and motivation, it lowered anxiety and promoted positive views on EFL learning, it could be concluded that VWs provided opportunities to solve problems related to affective side. Second, SL participants' engagement and participation in EFL classes can be increased by using SL. Tasks conducted in the VW of SL have also had positive effects on participants' communication anxiety levels.

In the introspective interviews, focus group, and individual semi-structured interviews, participants were asked about why they volunteered to choose SL instead of attending regular classroom sessions. Some preferred SL because they were more comfortable in SL; others enjoyed the topic-specific setting of SL. From the classroom perspective, this analysis can be discussed under the MATURAL dimension of the model. The NATURAL dimension suggests that Turkish EFL learners should be given opportunities to communicate in natural and stress-free environments. This suggested model can be checked via quantitative methods under the future model studies that explain WTC in English. As the participants of the study were first-year students of a state university in Turkey, future studies should determine whether similar results can be obtained from students of English as a second or foreign language contexts with different proficiency levels.

This study is not without some limitations. First and foremost, all the participants involved in this study are without previous experience in a VW environment and the novelty of such a Web 2.0 tool might have played a role on the results of the study. In addition, the study was conducted with a limited number of EFL students (experimental group= 30 and the control group=35).

Note: This study is produced from the first author's unpublished PhD thesis completed under the supervision of the second author.