Table 1. The Extent of Use of HC by Lecturers

The use of mobile learning spaces is an opportunity to break the boundaries of the classroom and to prepare teacher educators and pre-service teachers for future school classes. The purpose of this study is to examine the implementation of mobile technology and usage patterns in the mobile technology space among lecturers in a teacher education college and to examine the role of pedagogical support and guidance in relation to the methods applied and the attitudes of the lecturers toward teaching and learning in the mobile learning space. The paradigm of the present study is the mixed research model combining quantitative and qualitative research. The research population consisted of the faculty members teaching in the last 2 years in this learning space and eight pedagogical tutors and their mentors who got a tablet and were trained throughout the year to support and enhance their professional practice. The findings show st nd that in the 1 year, most of the lecturers did not use hybrid computers in the learning space. In the 2 year, when many of the technical difficulties were solved, more lecturers got pedagogical assistance, there were various uses of the hybrid computers for various activities. As for the pedagogical tutors, this study emphasized the significance of owning a personal and improved device, as well as providing the needed tools and assistance.

Fast-tracked technological development has been transpiring globally in the digital age. Consequently, numerous and recurrent changes should be introduced in our environment. The majority of teaching staff in teacher education programs were not born into the digitalinformational revolution, and so must prepare themselves for digital proficiency (ISTE, 2012; Kaufman, 2015). According to Daggett (2005), this calls for a shift in focus in order to address the increased incorporation of technologies. That is, from teacher-centered instruction to student-centered learning whereby teachers take a secondary position as directors, guides and supporters of the learning process. The researcher argues that this will facilitate students' development of leadership skills, teamwork and other competences necessary and relevant to challenging issues of our daily life. Hence, the education system should amend teaching methods designed for the oncoming wave of digitally-proficient students, their skills, experiences and needs.

Pre-service teacher education can be enhanced by mobile learning. This is manifested by different aspects of education, including, cooperative learning, contextual, constructivist and authentic learning (Patten, Sanchez, and Tangney, 2006). Other benefits are personalization/ “individuality” (Kearney, Schuck, Burden, and Aubusson, 2012), enhanced collaboration, access to information and deeper contextualisation of learning, and feedback (Koole, 2009; Sung, Chang, and Liu, 2016) and engagement, presence and flexibility (Danaher, Gururajan, and Hafeez-Baig, 2009). This requires educational design of Mobile Learning (ML) that can facilitate an experience of ubiquitous and seamless learning (Sharples, 2015). Mobile-based learning features enable location-based learning as well as other flexible, alternative teaching strategies and may be able to enhance the effects of pedagogies, such as self-directed learning, inquiry learning, or formative assessment (Sung et al., 2016). For that purpose, educators should be empowered so they can exhaust the potential of mobile learning anytime and anywhere through disruptive schooling transformation (Dede and Bjerede, 2011). However, there appears to be an important need for teacher training or teacher support with regard to the value of mobile technologies in the learning process. Thus, educators are able to effectively promote its implementation and integration in their classes (Kukulska- Hulme, Sharples, Milrad, Arnedillo-Sánchez, and Vavoula, 2009).

It should be noted that digital and wireless devices are usually developed for the market at large, but they are used by students in the learning process. “Mobility” as used in this paper refers both to the mobility of the physical technological device, as well as to the design of the learning processes applied by teachers (Traxler, 2007).

Teachers and students should be confident in using emerging technologies appropriately in order to teach in the 21st century. Naismith and Corlett (2006) indicate five factors for integrating mobile learning successfully: having access to technology, owning the technology, connectivity, integration of mobile learning into teaching and providing training and technical support. In addition, the concept of mobility describes the mobility of technology, the mobility of learner as well as the mobility of learning (El-Hussein & Cronje, 2010). Mobile technology used in teaching is defined as the various types of learning that take place in the mobile learning space designed to facilitate mobile learning practices. For the purpose of this study, hybrid computers were used as they enable its usage both as a tablet as well as a laptop. The use of mobile learning spaces, while considering the relevant pedagogical and technological factors, can allow preservice teachers going beyond the classroom limits and train them to enhance their students' learning.

The mobile learning can be used any time and anywhere. It facilitates a 5-level mobility: mobility in the physical space, technological mobility, mobility in the conceptual space, mobility in the social space and decentralized learning (Sharples, Taylor, and Vavoula, 2007). Naismith, Lonsdale, Vavoula, and Sharples, (2004) conceived a definition of a six theory-based categories of mobile activities, including behaviorist, constructivist, situated, collaborative, informal/lifelong as well as learning and teaching support. Squire and Klopfer (2007) maintain that individuality is the most unique feature which distinguishes between mobile devices and other technologies. Learners can feel they own the learning process, being independent and autonomous learning agents in their learning environment (Kearney, et al., 2012). Findings based on a meta- analysis and research synthesis on the effects of integrating mobile devices on learning performance by Sung and colleagues (2016) emphasize the significance of the instructional strategies, the pedagogical challenges and the matching of the unique features of mobile devices in order to augment the learning outcomes. Educators are required to pay attention to mobile technology features in order to harness them to teaching as well as to formulate and adopt an updated pedagogy. The innovative pedagogy focuses on the transition from teaching to knowledge building and changes the power foci of teachers and learners, learning activity, and the role of technology. Shulman (1986) conceived a model according to which the relation between the area of knowledge content and pedagogy are needed in order to define "teachers' knowledge". The necessary unique knowledge should be acquired by teachers, allowing them to teach various content areas by means of technology. Moreover, this enables them to aptly choose between learning contents, technological means and pedagogical aspects (TPACK – Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge) for the purpose of making an informed pedagogical use of technologies (Koehler & Mishra, 2005). According to Conole and Culver (2010), new technologies offer diversified opportunities for innovative, proactive, and effective learning. However in practice, teaching reproduces the frontal teaching, disregarding the possibilities offered by the technology. The researchers stipulate that this is due to the fact that teachers are unaware of the potential embodied in the new technologies. Moreover, they are incapable of designing learning activities which effectively make use of the technology. In a changing world, whereby Information and Communication Technology (ICT) activities are currently integrated into teaching, educators should adapt teaching methods to this new situation. Puentedura (2011) suggests the SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition) model for characterizing the level of technology-integrated teaching. This model consists of four levels: The last level is parallel to the high levels of thinking – synthesis and assessment – leading to teaching and learning models which differ from those not using technology. Puentedura's SAMR model befits Sung and colleagues (2016) meta-analysis findings, which suggest a longer intervention duration, a more closer technology and curriculum integration, and further evaluation of higher-order skills. Additionally, the authors suggest to extend the dependent variables beyond content knowledge so as to consist of skills such as problem-solving,critical thinking,interactive communication, or creative innovation and thus be more evincive. In addition to the theoretical models implemented, the design of the space, where learning occurs has subsequent effects in influencing teacher pedagogies and practices and therefore students learning (Blackmore, Bateman, O'Mara, Loughlin, and Aranda, 2011). Similarly to the integration of any technology, integrating mobile technologies in teaching entails concerns apprehensions about the application of technological capabilities and effective ways of technology-integrated education.

Educators can implement mobile technology-integrated teaching in order to narrow the chance for a gap between the school and the extracurricular environment. The result of using technologies in which they are versed can empower learners, enhance learning, rendering it more meaningful and relevant. Laurillard (2007) suggests in this context to adopt a pedagogy that both promotes quality learning and is more sustainable and flexible than traditional teaching methods. It is crucial trying to understand the type of exercises required for learning complex concepts and higher-order thinking skills, developing pedagogical applications that yield the desired learning results. Similarly, Sharples (2007) argues that, in order to develop innovative educational activities,one should integrate technology and learning, whereby the driving forces are pedagogy and learning theories rather than technology. Naismith and Corlett (2006) also review technologically-oriented pedagogies and suggest taking advantage of the unique technology affordances that can contribute to an enhanced user's experience: create fast and simple interactions, prepare wide-context materials that can be accessed in an easy and flexible manner, implement in learning the benefits of mobile devices and use them to support learning. According to Kearny, et al. (2012), this facilitates the development of authentic tasks, learning in a variety of spaces and enhancing immediacy and connectivity. Sung and colleagues (2016) meta-analysis findings suggest more indepth experimental research into how educators find a common ground for hardware, software, lesson content, teaching methods, and educational goals to achieve what they call orchestration. For this to happen, the authors suggest providing various educational activities that have already proven effective while using different learningoriented software programs, indicating the wide range of applicable educational applications. The authors suggest as well to strengthen professional teacher-development programs so as to provide sufficient preparation of the teacher, the most significant obstacle to implementing effective mobile learning.

The purpose of this study was to expand the scope of the pilot study previously conducted (Seifert, 2015) and to further examine the implementation of mobile technology and identification of usage patterns in the Mobile Learning Space (MLS) among the lecturers in a teacher education college. Furthermore, the study aimed to learn the usage patterns of the Pedagogical Tutors (PT) and their mentors who were provided their own tablets throughout the year, as well as exposure to ways of implementation in their various domains. Another objective was to set the potential of mobile technology for teaching on the challenges which this combination conveys. Accordingly, patterns of teaching and learning were examined in the MLS, as well as the role of professional development, pedagogical and technical support and guidance in relation to the methods used in the MLS and the lecturers' attitudes towards teaching and learning in the MLS.

This study was conducted during two years. The first year, constitutes a pilot study, in which technical difficulties were solved, lessons were learned and the MLS was adjusted to the lecturers' needs. In the second year of the study, the emphasis was placed on the professional development and pedagogical training of the lecturers.

Out of the 29 lecturers who taught in the MLS, 22 lecturers taught one course, four lecturers taught two courses and three lecturers taught three courses. Among the courses being taught in the MLS were: Customized instructions in reading and math, learning to think: A combination of thinking cultivation at instructional levels, Multiple intelligences in the classroom, A didactic workshop on biology and in business management, Collaboration in Information-intensive environments, Leadership in practice, Branding and marketing educational institutions, Leadership development of teaching, Change processes and implementation of changes in education systems, Qualitative research. At the end of the first semester, seven lecturers responded to the questionnaire while six lecturers responded at the end of the second semester. In order to maintain the participants' anonymity, the names of the lecturers were replaced by fictitious names.

In the first semester of the second year, 16 lecturers were assigned to teach 17 courses in the MLS. Five courses were taught along the whole year and 12 courses only in the first semester. At the end of the first semester, 13 lecturers responded to the questionnaire. In the second semester of this year, 13 tutors were assigned to teach 18 courses in the MLS. Among the lecturers, two lecturers taught two courses and one taught three courses. The rest of the lecturers taught one course each. In total, seven courses were yearly and nine courses were taught in the second semester. For nine of the lecturers, this was their second year assigned to teach in the MLS.

During the second year, eight PT and their mentors got a personal tablet for the whole year and for the following one.

The research questions were:

During the academic year 2014, a mobile learning space comprising 26 Hybrid Computer was built. The planning of the space was underpinned by the thought that perhaps this space was not necessary for the purpose of teaching mobile learning applications. The lecturers can settle for available mobile computers and tablets which will serve for a variety of applications and activities, independently of the space and the lesson time. Following the contribution of HCs, the college has decided to make use of this space as modeling of varied uses for the pre-service teachers and for creating an innovative and diversified teaching. The latter included four portable white boards and teaching and learning processes beyond the class boundaries as well as examining models to be used in this kind of space. The college made arrangements for launching the space, which consisted of technical and pedagogical aspects. The first semester was mainly designed for providing a technological response. Only towards the second semester, pedagogical thinking was initiated with some of the lecturers who taught in the space. Following the first year pilot, lessons were learned and prior to the beginning of the year, workshops were offered to the lecturers as well as pedagogical and technological personal assistance. Prior to the planning of the space, several aspects had to be considered: the space location, space organization, staff training, managing the use of the space, technical support while using the space, pedagogical support, radiation safety, security of the equipment and interactive board.

The research participants included the faculty members teaching in the course of the first year. In the first year, out of 29 lecturers assigned to teach in the MLS, 13 responded to the questionnaire. In the second year, 13 instructors were assigned to teach in the MLS. All the 13 instructors responded to the questionnaire. Five of the lecturers were assigned to teach in the MLS during both years of this study. The age of the lecturers assigned to teach in the MLS ranged from 43-65. All the lecturers held a Ph.D. Two related technical support people and two members of the ICT unit provided pedagogical support. In addition, this study included eight novice PTs in the 'Master of Education in Teaching' program and their two mentors. The PTs participated in a 120 hour workshop along, which aim was to expose the PTs to innovative pedagogical training as well as pedagogic approaches regarding the integration of technology in the curriculum in an informed way. The pedagogical assistance was conducted by the two members of the ICT unit. The age of the PTs and their mentors ranged from 38-56. All the PTs held a Ph.D. In total, 37 instructors and 10 pedagogical trainers participated in this study.

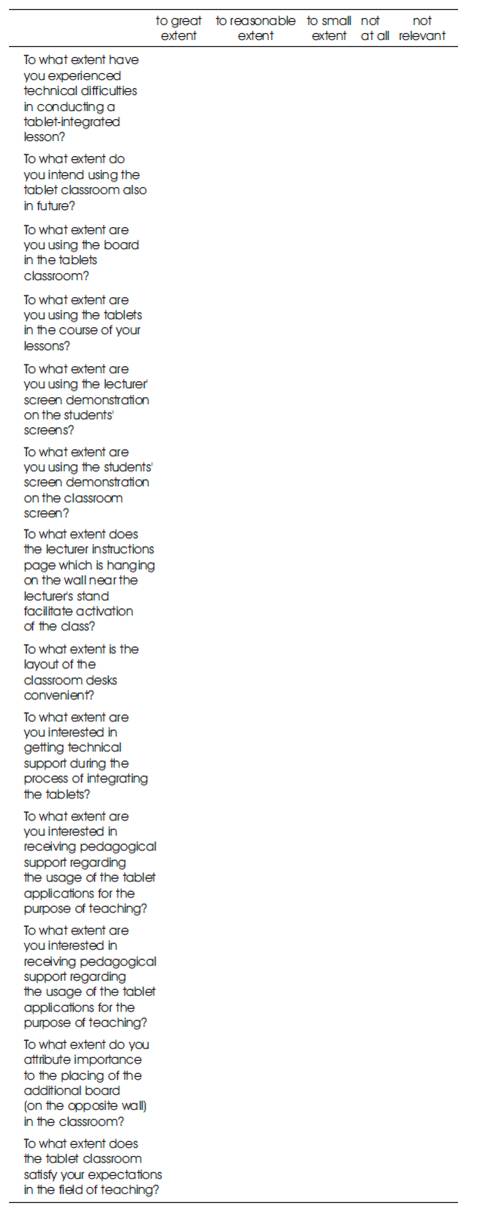

This study employed a mixed-method approach which combines quantitative and qualitative research methods (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Keeves, 1998). The method approach included questionnaires, semistructured interviews, a focus group, 3 video taped observations and information minutes of meetings. The research tools included a questionnaire (content validated by three instructional designers) administered to lecturers at the end of the two semesters in the first two years of implementation (Appendix A). The lecturers were informed that, their participation is entirely voluntary in the study and their responses are completely confidential. The survey comprised of three main sections. The first section consisted of 5 items that represent the faculty members' personal information and information regarding the course/s they taught (age, tenure, course subject, number of semesters taught in the MLS, course duration). The second section consisted of 8 items that represent the lecturers' information regarding the type of use they implemented in the MLS. The third section of the survey consisted of 6 open ended items aimed to give a broader view with regard to implementing the ML in higher education and MLS role in teacher-preparation. A four point Likert Scale with Strongly disagree (4), Disagree (3), Agree (2), Strongly agree (1), has been used for the items representing the type of use the lecturers implemented in the MLS. Simultaneously, three lessons were videotaped in the MLS and then analyzed.

Semi-structured interviews (comprised mainly of part two and part three of the questionnaire) with five of the lecturers and with the support staff as well as meetings with the leading faculty in the college and information minutes of meetings were held throughout the year. The semistructured interviews, ranged from 45 to 60 minutes in length, were conducted with instructors of different disciplines: Science, Instructional Design, Pedagogical Training, and English. The lecturers and tutors were asked regarding the use they made, challenges as opposed to problems they faced as well as their suggestions for improving the MLS usage.

In addition, a focus group was conducted with the eight PTs and their mentors, who owned tablets, at the end of the first year during a three hour discussion, in order to gain insights on the implementation obtained when owning a personal device and being offered personal support (comprised mainly of part two and part three of the questionnaire). Since only two of the PTs were assigned to teach in the MLS in both years, they responded to an adjusted questionnaire.

Data were obtained regarding the practices applied by lecturers who taught in the mobile technologies' space and teachers' extent of using the mobility features of Hybrid Computer (HC). In addition to the quantitative findings, and as part of the qualitative analysis, lecturers expressed their opinion in the open-ended items. After the transcription of the interviews, in a process of open coding, categories were created and more general themes were identified from those categories. The analysis was guided by “a ladder of analytical abstraction” in order to identify patterns and propose explanations, identify themes and summarize interviews, documents and meetings' summaries (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The mixed-method approach was useful due to the small sample and due to the fact that some of the participants were not available for conducting an interview, as it enabled further analysis of unpredicted quantitative results and provided an enhanced understanding of the results (Creswell, 2009).

This chapter presents the quantitative and qualitative findings with respect to lecturers as derived from various data. The analysis of the qualitative and quantitative data yielded a few main themes: 1. The extent and type of use of the HCs; 2. Pedagogical and technical support; 3. Technical difficulties; 4. Organization of the learning space; 5. Attitudes towards teaching and learning in an MLS.

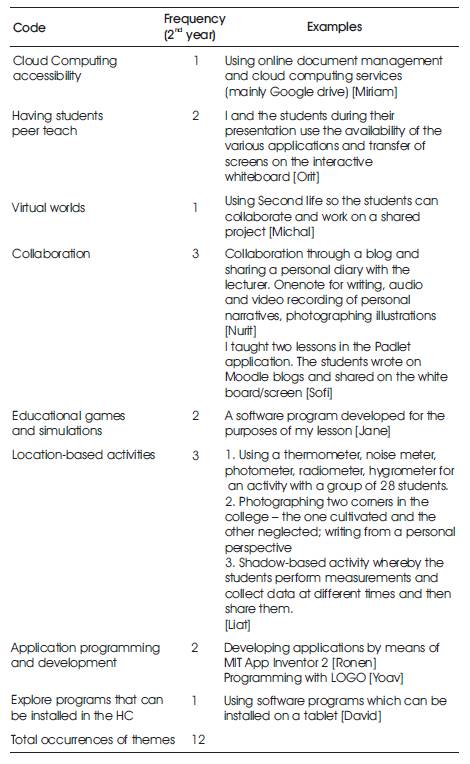

In both first and second years, there was a limited use of the HC by lecturers. Table 1 presents the extent of the use of the HC by lecturers.

Table 1. The Extent of Use of HC by Lecturers

As Table 1 illustrates, lecturers' answers convey a limited extent of using the hybrid computers in the first year (M=1.7, SD=1.30) and an increased use in the second year (M=2.5, SD=1.27).

Three main patterns of use by the lecturers were identified during the first two years of implementation: Use of the HC as a laptop or desktop (common use), use of the HC for running applications (reasonable use) and the use of the HC for location-based activities (limited use). Table 2 presents the three patterns of use and excerpts from the lecturers' assertions.

Table 2. Lecturers (N=13) Excerpts Regarding HC Usage

Certain lecturers had no intention of using the computers at all. Nevertheless, since they were available in the MLS, they used them for surfing the Internet, writing and editing, as part of their planned lessons. Some lecturers used the HC for collaborating while a few made use of social networking and the cloud computing. Other instructors decided to use the students' smartphones for the given tasks and in this case, only those students who did not own a fitting one were provided with a HC. Analysis of the observations of the three videotaped lessons revealed diverse uses of the HCs. One lesson involved collaborating in class by using playlists on YouTube, as well as creating and communicating through the students' own discussion on Facebook. In the second lesson, the HCs were used for drawing and presenting the drawings on the interactive whiteboard. In the third lesson, the HCs were used for an activity based on QR Codes which students conducted beyond the class boundary. Although the use of HC was limited, some of the lecturers who had used the hybrid computers introduced a variety of uses and applications. Some students wrote on Moodle blogs on their HCs and shared their writing on the whiteboard/screen. Others created collaborative Google Docs on their HCs, which their lecturer then shared on the whiteboard for all the class to see and give feedback. Another activity involved explaining meaningful teaching and learning through text, pictures, video and sharing via the Padlet application. Finally, one classroom utilized online document management and cloud computing services via their HCs.

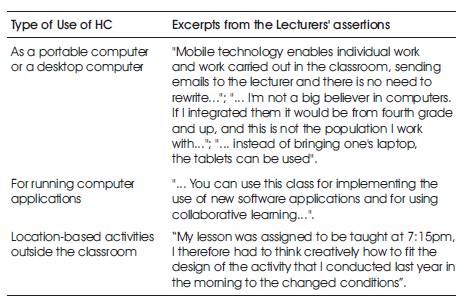

The quantitative data provided information on the extent to which the HCs were used by lecturers and students, and the type of use they implemented. Table 3 presents the type of use of hybrid computers lecturers made during their lessons.

Table 3. The Type of Use Lecturers Made with HC (N=13)

The few lecturers who used the HC during their lessons mainly used them for running applications (23.1%), for using Office software and accessing the Internet in order to retrieve information (15.4%) and for location-based activities (23.1%). These findings show that, most of the lecturers did not use HC in the learning space for various reasons: some need technological and / or pedagogical support, some believe that it is not relevant to their teaching. Table 4 presents additional uses by the lecturers.

Table 4. Additional Uses Lecturers Performed (N=13)

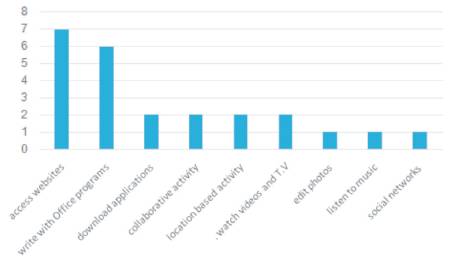

As for the PTs who owned the tablet along the year, Figure 1 presents the uses they made.

Figure 1. Uses Made by the PTs

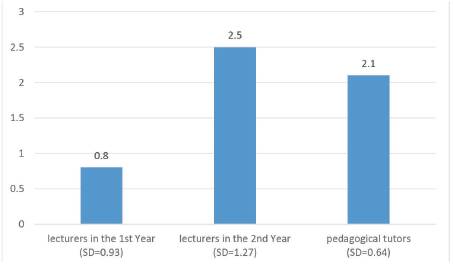

Figure 1 illustrates that, most of the PTs used the tablets for accessing websites as well as for editing with Office programs. There was less use of downloading applications, conducting collaborative and location-based activities. The lecturers and the PTs were asked regarding their use of the tablets. Figure 2 presents the comparison between them.

Figure 2. Average Level of Tablet Use Made by the Lecturers and the PTs

As illustrated in Figure 2, there was a difference between the level of use both the PTs and the lecturers made in the first two years. While the lecturers reported limited usage in the first year, in the second year the level of use is significantly higher (M=2.5) with a large SD (1.3). As for the PTs, they made a reasonable use of the tablets (M=2.1, SD=0.6).

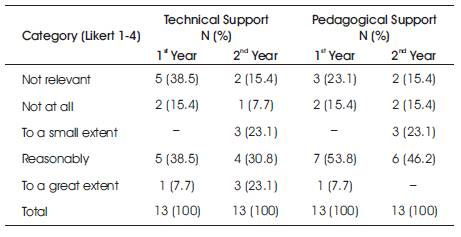

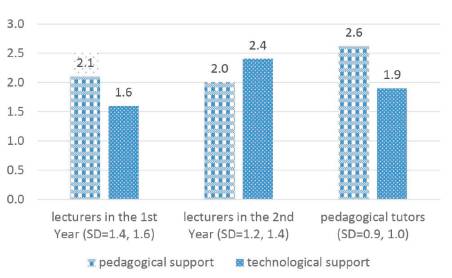

The lecturers were asked to which extent they wished to receive technical and pedagogical support. In the 2nd year, the lecturers were willing to get technical support at a higher level (M=2.4, SD=1.4) in comparison to the pedagogical support they were willing to get at the same year (M=2.0, SD=1.2).

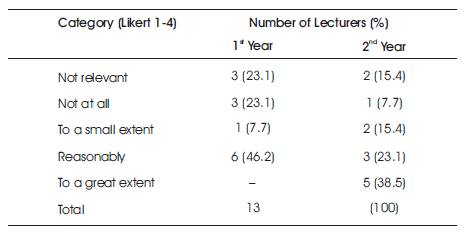

Lecturers' answers are presented in Table 5. Table 5 shows that, about half of the lecturers are interested in technical support (46.2%) and over half of them (61.5%) are willing to get pedagogical support. Lecturers that did not receive pedagogical and/or technological support regarding the use of HC, did not use the HC during their lessons. The importance and necessity of support becomes very prominent. Some of the lecturers are interested in having practice time in order to get familiar with the learning space, equipment and functionality.

Table 5. Lecturers' Wish to Receive Technical and Pedagogical Support (N = 13)

Some of the lecturers (30%-40%) say that hybrid computer and/or laptop are not relevant to their work and therefore they have no interest in technical or pedagogical support. Sometimes they also explain the lack of relevance from their perspective. One of the lecturers stated her preference to continue teaching in the traditional way as in her opinion, it saves time and enables her to control the learning process. Says Sarit: “As the semester started, there are many tasks to complete, and the time available is restricted and so it becomes an expensive resource. For me it is tempting to teach in the old known way”. Some of the lecturers express a wish to get pedagogical support in the use of HC for the purposes of teaching. Prior to getting pedagogical support, lecturers are primarily using the HC for Internet access, using Office, drawing, introducing applications to their students with special needs and downloading applications. Half of the lecturers who responded to the questionnaire have the intention of using mobile technology in the future, given the appropriate support. Other lecturers have raised the challenge of having to rethink the lessons' properties and means of transmission. Limor offers: “It is important to rethink characteristics of the lessons and of teaching methods”.

When asked in the 2nd year, what kind of requests they got from the students, the lecturers reported mainly requests related to technical problems: battery problems, the Internet was slow, especially when all the students simultaneously accessed the same applications and when students worked with diverse media resources. Some of the students needed assistance in operating the tablet. One of the lecturers who used the tablets along the year stated: "I am definitely a technophile. Thus, if there are tools which I need but am not familiar with them, I simply play and get friendly with them rather than go to organized tutorials". Says another tutor: “The experience of the support and assistance is strong and agreeable”. In addition to getting the needed assistance, a question remained with no firm answer, with regard to who the responsibility is to distribute the mobile technology, and make sure that all devices are back to their place and recharged.

The lecturers responses regarding their willing to get peadagogical and technological training were compared to the responses of the PTs. Figure 3 presents the comparison between them.

Figure 3. Average Level of Willingness to Get Pedagogical and Technological Training by the Lecturers and the PTs

As illustrated in Figure 3, there was a difference between the level of use both the PTs and the lecturers made in the first two years. While the lecturers reported limited usage in the first year, in the second year the level of use is significantly higher (M=2.5) with a large SD (1.3). As for the PTs, they reported a level of usage of 2.1 (SD=0.6).

Many of the lecturers reported facing difficulties using the HCs and using the interactive whiteboard. The interactive whiteboard was used in the 1st year by 77% of lecturers due to the fact that this was the main board and it was connected to the lecturers' work station. Lecturers learned how to operate and use it and most of them used it reasonably. Most lecturers used the interactive whiteboard (77%) while others did not use it (M = 2.3, SD = 1.4). One lecturer indicated that, the interactive whiteboard did not satisfy his needs, three lecturers (23.1%) indicated that it did not serve their needs and nine lecturers (69.2%) indicated that it met their needs in a reasonable manner (M = 2.6, SD = 0.7).

In the 2nd year, all the lecturers used the interactive whiteboard. Most of them were satisfied with the use of the interactive whiteboard (M=3.5, SD=0.7). 84.6% of the lecturers presented their materials from the teacher computer, 76% used their hands to change the screen, to resize the objects on the screen and perform other actions. Only 23% of the lectures answered that they used the interactive whiteboard to as a traditional whiteboard. 14 says... “It is possible to increase parts of the presentation on the ITB screen, to move the slide presentation in a cool way, draw on the presentations and mark things through discussion’. 7 says... “You can write on the board without a pen!". The option of displaying the lecturers' screen was applied to small extent (in the 2nd year: M=1.5, SD=1.3) and did not give an adequate response in terms of quality. The option of introducing the students' screen monitors in the interactive board was applied to small extent (in the 2nd year: M=1.3, SD=1.2) and was considered by the lecturers as cumbersome and inadequate in terms of quality.

The lecturers used the interactive whiteboard for projecting presentations, movies, activities and as a multimedia tool. Some lecturers used it for projecting collaborative work completed during the lesson. The lecturers reported using the second interactive whiteboard in the class for presenting instructions on one board and answers on the other for the purpose of drawing attention. Moreover, they applied it for collaborative work, when students are divided into groups and can thus present their product on a full screen. Says one of the lecturers: “I must avoid touching the board which has simultaneously a double function: a dynamic presentation to the pupils as well as an input interface for the system. Had the designers consulted me, I would have suggested (as in the case of the 'virtual' keyboard) that whenever necessary a window would be opened on the board displaying a reflection of the presentation and/or input options for exploiting the 'interactivity' rather than turning the entire board into a huge monstrous tablet”.

Although the technical support was available, lecturers reported technical difficulties which included: sensitivity of interactive whiteboard leading to unexpected situations and difficulties operating it, sound problems, the fact that the room was not always opened on time, difficulty writing on the board. In the 2nd year, there was a decrease in technical difficulties (M=2.0, SD=1.4) as compared to the 1st year (M=2.5, SD=0.9). 6 says... "There are problems with electricity on the desks around the classroom, it is very difficult to connect everything and the electrical wire causes chaos". 14 says... “Improving the wireless network which does not always functions well… we used it in one lesson when we had to photograph with the camera in it. But the photography software did not function in most of the tablets". Dana, a lecturer in the course sums this up: "… the biggest challenge is starting the lesson on time when all the functions are working and the room is arranged according to my request…". The level of technical difficulties reported by the PTs is M=2.6 (SD=0.7).

In order to overcome part of the difficulties, it is very important to support lecturers and aid them feel at ease when using technology. Lecturers prefer mentoring and are not interested in guidelines relevant to the use of space. Lack of control and familiarity with the implementation and harnessing of mobile technology in favor of teaching brought students to express the following words. 4 says,... "We used only once the tablets and the smart board. It is a pity we did not make more use of the learning space". And 6 adds: "... Today, as every student has a laptop this MLS is redundant...".

As for the PTs, they reported facing problems with the keyboard, which they considered very unfriendly. It caused an inability to write in a row and as a result the lecturers avoided using it. Another user complained about having to use Microsoft cloud computing storage services in addition to the one he already uses, due to the limited storage space of the tablet. One user protested against having to use the tablet for photographing a peer teaching activity since he faced a problem of restricted space and the difficulty to upload the file to the institution's cloud computing storage. Other complains related to the short cable enabling flexible movement in the learning space as well as exhausted battery life.

Organization of the learning space often dictates the ways of usage and is also derived from the application of teaching methods. The lecturers were asked about the extent to which the learning space meets their needs. Table 6 presents lecturers' answers.

Table 6. The Extent to which the Learning Space Meets the Tutors' Needs (N = 13)

As shown in Table 6, some of the lecturers were not satisfied with the space design. Certain lecturers were bothered by the fact that the space design prevented the sense of the group while working in groups. In the 1st year, lecturers demonstrated a low level of satisfaction with the space design (M=1.8, SD=1.3). In the 2nd year, they were more satisfied, but still the SD remained high (M=2.6, SD=1.5). Suggestions regarding the organization of the learning space were made by the lecturers.

Says Nava "... As for the chairs, on the one hand, I would recommend bringing flexible chairs that come with a small table. On the other hand, high mobility can distract students with learning disabilities...". 11 says: "... The MLS is very easy to use with laptops. There are many electrical outlets and the special interactive board is very convenient and practical for lecturers who use it properly...”. It was proposed to have a larger MLS with a more flexible arrangement, so that the space is suitable for working in groups as well as in a circle of chairs or in a u-shaped format. The lecturers mentioned the challenges that such MLS poses to lecturers – the lecturers mentioned a few issues: (a) Need to rethink the characteristics of their lessons and the teaching methods; (b) The need to know how to apply the different functions and gain pedagogical and technical support; (c) The possibility to conduct advanced lectures while typing on the tablet and presenting on the interactive whiteboard while moving around the space.

In the 2nd year, the lecturers requested more flexibility in organizing the MLS and a possibility to rethink the size and design of the MLS, have the room more available or alternatively, have additional MLSs to allow its use by an increasing number of teachers and students as well as having MLSs which can be used with large size groups. The lecturers thought that professional development with regard to the use of MLS is crucial for its effective use.

As for the PTs, only two of them used the MLS for a few lessons when it was available, or when the lecturer assigned to teach in the LMS could switch the learning space with them. A conversation with the PTs and their mentors at the end of the year demonstrated that those who mostly used the tablet, were those who were willing to get pedagogical training, to use mobile learning with their students and were willing to use the tablets in the future.

The main objective in teacher education is to prepare the pre-service teachers for implementing at school what they have learnt. Although the findings indicate that, there was a low rate of teaching with HCs, the answers to the openended questions and the conversations held demonstrate a desire to study and learn the use of HCs and the operation of the MLS. Still, the level of implementation mostly remained using the HC as a laptop. Tutors were able to run applications with technical support. However, for conducting collaborative and location-based activities exploiting the mobility of the technology outside the learning space, lecturers needed pedagogical training and assistance.

In the 2nd year, when the lecturers were asked whether they intend using the MLS and the HC, in the future, most of them were strongly positive, whereas about 38% were not that positive (M=2.7, SD=1.7). In the 1st year of implementation, the lecturers' response was lower (M=2.3, M=1.7). One of the lecturers stated: “being assigned to teach in the MLS created for me an opportunity. It enabled me to use the available technology and after I tried it, I became encouraged to use it a few more times along the course and gained the assistance that has been offered to me”.

Lecturers were mostly positive in implementing mobile learning after receiving technical and pedagogical support. As for the students, it is important to expose them to varied and innovative teaching models as well as help them develop attitudes and deal with mobile technology implementation in their classrooms.

As for the PTs, during the focus group meeting, all stated that they intend using the MLS at a reasonable degree. They recommend having a kind of tablet that can suit their needs and the ability to share and store data via cloud computing. This should be a high quality and advanced new generation tablet, which allows downloading all needed applications and is suitable to their varying needs.

The study emphasizes the fact that lecturers and PTs should be made aware of the potential encompassed in the new technologies and get help in developing competencies necessary for shaping learning activities which effectively use the technology and enhance learning. When they gained pedagogical and technological support, lecturers tended to incorporate more contextual, authentic, constructivist and collaborative activities, as described also by other researchers (Dagget, 2005; Patten, et al., 2006; Naismith, et al., 2004; Kukulska- Hulme, et al., 2009; Sung, et al., 2016). Some lecturers became aware of ML by being assigned to teach in the MLS and by being offered assistance and mutual thinking. Out of the five levels of mobility described by Sharples, et al. (2007), this study found two major patterns of HC implementation. The first is technological mobility in the social space, as demonstrated by the facilitation of collaboration. The MLS facilitated collaboration, group work, lessons where students move easily around the learning space and prompted lessons where various types of activities are designed and implemented along the course in a spontaneous and creative way, facilitated through the pedagogical assistance and the professional development provided. The second pattern of mobility involves the physical space, which prior to HC implementation had been restricted to the classroom. This pattern was partially achieved. The lecturers who explored the flexibility of using the devices around the campus, learned that for some activities it would be more suitable to use the students' smartphones and thus, bypass the inconvenience of having to upload the work from a nonpersonal device. Lecturers and students who owned a personal mobile device, as supported by other studies (Kearney, et al., 2012; Sung, Chang & Liu, 2016), could benefit from the personalization/”individuality” attribute, that appeared to be essential for promoting the incorporation of ML. In addition, those who possessed a laptop which functioned as a tablet as well, could achieve the level of mobility in the conceptual learning and decentralized learning, and thus benefit from a higher level of flexibility and efficiency. It is suggested to explore all five levels of mobility conceived by Sharples, et al., as part of the teacher training in the MLS. There is a need to make faculty aware of the various applications and develop their confidence in and awareness of using the most suitable device and activity to their learning objectives. It is evident that for best practices of ML to occur, it is necessary to obtain the mobility by providing access to suitable technology, as well as to design the learning activities for enhancement of the learning process.

Implementing ML as with implementing any other technology, requires a gradual process. In this study, it is learned that in the second year, lecturers who were involved in the process, could see the added value of integrating ML into teaching and tended to increase ML. Some of the instructors who were assigned to teach in the MLS taught without exploiting the HC or in some cases implemented technology at a substitution level (Puentedura, 2011). However, lecturers who were assigned to teach in the MLS yearly courses or for more than one semester, were more likely to use the HC during their lessons. These instructors made more informed use of technology with regard to the content explored and to the pedagogical aspects implemented (Koehler & Mishra, 2005) in order to augment, modify and even redefine their lessons (Puentedura, 2011). There were several instructors who prepared a few lesson plans gaining pedagogical and technical assistance and used the lesson plan with minor changes in each of their classes, during consequent semesters. The more they taught in the MLS, the more they could be comfortable in exploiting the flexibility that the time-space facilitated. Thus, they impacted their pedagogy and affected their learning experience (Blackmore, et al., 2011) and benefited from the potential of transforming their way of teaching (Dede, 2011; Sung, et al., 2016). As for the PTs, they were experts in their domain, but novice to many concepts of pedagogical training and digital technology, and were therefore open to gaining new insights with regard to the implementation of the desired content along with pedagogy and technology (Koehler & Mishra, 2005).

As for the role of technical and pedagogical training, the results show that most of the lecturers are not aware of the various possibilities of implementing ML and do not seek to do so in the first place. The more oriented technologically tended to be more willing to implement ML and persevere, while the others needed more assistance along the learning path. However, once lecturers are exposed to ways of implementation and of best practices from which they and their students can benefit, they gain confidence and are encouraged to take advantage of the professional development that is offered to them. Hence, they become more independent and capable of implementing ML in a way that conveys seamless learning (Sharples, 2015). Following this study, it is important to provide resources to lecturers who promote innovative teaching models and help them become acquainted with the properties and benefits of this technology. They should also be aware of the difficulties that are part of the process of implementing a new technology. The more educators are aware of the potential of the use of mobile technologies, the more questions they may have and therefore seek more support and rethink their current pedagogy and conduct a more sophisticated and efficient implementation of ML. The model of Puentedura (2011), with its several levels of ICT integration, provides a useful tool for mapping this transformation of technologybased learning. Technology-based learning activities should not be aimed merely at replacing older tools. Rather, they should aspire to re-define the learning process and learning method and hence increase the level of interest and engagement. In addition, it has been clear that the design of the learning space dictates its usage. Therefore, it is suggested to obtain various MLS, designed to move around flexibly so that various types of innovative pedagogies can be further developed.

Conole & Culver (2010), Laurillard (2007) and Sharples (2007) argue that, pedagogy and learning theories should drive the use of technology. Similarly, this study emphasizes the importance of providing close, personal, constant assistance to lecturers. Moreover, it is recommended to makelecturers aware of the available support in the institute, offering them personal support. Only some lecturers responded to the offer of personal support, and it was these lecturers who reported a high level of comfort and competence with the technologies, and went on to successfully implement them in the classroom. The tutors who gained support as part of their training, benefitted more of the assistance and were more open in gaining future assistance. Lecturers who did not take advantage of the support services offered, usually due to lack of time as reported by them, were not as comfortable with the technologies and the learning space they created was that of a traditional classroom. There is a need for further experimentation with the motivation of lecturers who are less technologically-inclined, so that the potential of an MLS is made clearer to them.

The researchers are now after the second year of teaching in the MLS. At this stage, they have focused on observing and defining learning needs, as well as supporting the lecturers in implementing these relatively new practices. There was tension between the mobile potential of the HC versus its fixity in the MLS, ownership of the college versus personalization by the lecturers and students and the large demand on the MLS. Some of the challenges have been resolved. For instance, since the devices belong to the institution, lecturers and students are offered the option of using the college cloud computing, so that they can access their work from their own devices as well. Moreover, there is consideration in financially helping students to own their own devices. Attempts are made to provide instructors with HCs for short periods of time, so they can conduct with their students ML oriented activities.There is still much to be examined, however says one of the tutors: "It is our responsibility for educating a future teacher who knows how to apply basic technology, is not afraid and can integrate it in planning the lesson, in practice and assessment”.

As for the PTs, the more sophisticated the use they made the more technical problems they faced. It is not enough to possess one's own device. It is crucial that the device enables various and sophisticated activities and is not restricted to basic use. In addition, it is essential to offer the lecturers a positive experience within teacher development programs along with their practice in class with their students,so they can form an opinionon applying ML and express their willingness to implement its use in their teaching (Sung, et al., 2016).

The mobility of the HC facilitated implementation of authentic tasks that could be performed in a variety of spaces while exploiting the immediacy and connectivity of mobile learning (Kearny, et al., 2012), even for lessons that were not assigned to be taught in the MLS. Certain lecturers found it difficult to incorporate certain applications with the HCs. In the educational context, we would like to see HCs that allow multiple OSs so tutors and students can become familiar with as many available educational applications as possible, more connectivity, collaboration and data sharing with other users and redefinition and expansiveness of learning and teaching. Figure 4 summarises the different facilitators of mobile learning implementation by lecturers and tutors.

Figure 4. Facilitators of Mobile Learning Implementation by Lecturers and PTs

As Figure 4 indicates, for the paradigm shift to occur, preservice teacher need to be exposed to various types of learning, to mobile learning spaces as well as to available technologies. Moreover, there should be institutional support as well as institutional culture that encourages various types of learning, motivates and rewards them. Lecturers on their turn, while owning a device, can gradually broaden and deepen their experience and gain self-confidence while implementing mobile technology in their lessons. It is recommended that the institution provides mobile devices to lecturers who are willing to lead the adoption of these technologies in students' teaching practice, so they gradually get self-motivated and gain more experience. It could be that for those instructors who felt “jumping on the bandwagon at the last minute”, the unique features of mobile technology, helped them to bypass the barriers they faced with immobile technology, and lead to more active and innovative teaching methods, where students are engaged and more actively involved (Sung, et al., 2016).

During the transition period, lecturers should get long term mobile technology use, with the appropriate supporting logistic, and be exposed to the practices of other lecturers. This can gradually lead to being able to expand the incorporation of units that exploits the mobile technology benefits and be a role model to pre-service teachers, promoting innovation in education (ISTE, 2012; Kaufman, 2015).

As for the limitations of this study, the findings may have limited generalizability to the broader population, due to low statistical power of the small number of participants. Since the study was conducted in one college of education, which is not representative of all colleges of education in the country nor in a wider context. For maximizing lecturers' responses, a similar study should be conducted with a larger population of lecturers and students, and in-depth interviews performed with a large number of both instructors and PTs in consequential years, to determine the technological and pedagogical needs of different educators from various disciplines and learn the impact it has on pre-service-teachers and whether it enhances their ability and willingness to implement this technology in their classrooms.

Nonetheless, the findings obtained can highlight some best suitable models for implementing mobile technologies in teacher education institutions and contribute to decision-making about the acquisition and design of the technological learning spaces in teacher education colleges. Another benefit derived from this experience is the importance of thinking about the design of technological spaces (Blackmore, et al., 2011) while relating to the different teaching preferences as well as to the learners' differentiation in order to have a positive impact both on teaching and learning. A gradual introduction of mobile technology can extend lecturers' confidence in using emerging technologies appropriately and can open up opportunities for a wide variety of pedagogical patterns and teaching practices.

Dear lecturer,

At the beginning of the academic year 2014 we inaugurated the tablets classroom. At the end of the second semester we wish to examine the various forms of use of the mobile technologies implemented in the classroom, the experienced difficulties, the various needs and the issues which should be improved. Moreover, we like to know whether you are interested in a thinking session regarding the use of tablets for your own needs towards the coming year.

Thank you for your cooperation.

The questionnaire includes items related to your usage of mobile technologies as well as items associated with your usage of the screen (board) in the tablet classroom.

1. In what way are you using the interactive screen in room 190?

a. Presentation on the board from the lecturer's stand.

b. Using a pen for writing on the board.

c. Writing on the white board with a marking ink or your fingers.

d. Using the hand and fingers for changing screens, expanding the screen, reducing the screen and other changes in the screen.

2. To what extent do you use the tablets in room 190 for teaching purposes?

a. I don't use the tablets.

b. I used them for a lesson or two.

c. I constantly use them during the lessons.

d. Other, please specify.

3. Are there applications or activities which you wish to implement but cannot do so?

4. For what purposes do you use the tablets? (please choose all the applications).

a. Access of Internet sites.

b. Writing with Windows 8 / office software programs.

c. Downloading of applications from Microsoft shop.

d. Experience of place-based activities – outside the tablets classroom.

e. Collaborative activity.

f. Other, please specify.

5. Please specify additional forms of using the tablets and explain the existing forms of usage.

6. To what extent does the board (screen) in room 190 provide a response to your teaching needs?

a. To great extent.

b. To reasonable extent.

c. To small extent.

d. Not at all.

7. For what purposes do you use the board in room 190?

8. The following items relate to the usage you make of the tablets and to forms of usage you would like to implement.

9. What is the students' attitude towards the usage of the mobile technologies classroom?

10. What addresses, questions and/or requests associated with mobile technologies did you get from the students in the course of the lessons?

11. Are there any applications, topics or activities which you would like to implement in the room but cannot implement them in this room? Why?

12. What are your recommendations regarding the usage of the additional board in the classroom for teaching and learning needs?

13. What difficulties (or alternately – challenges) does the room set for your practice as a lecturer?

14. What would you change towards the next year?