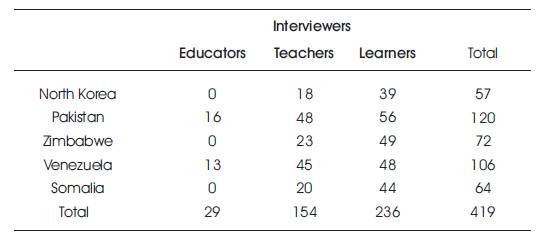

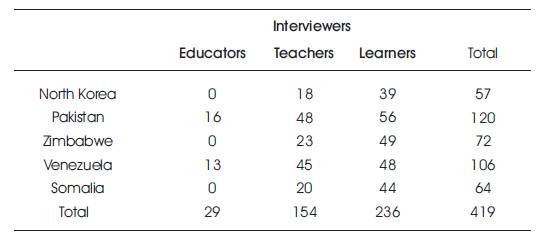

Table 1. Participants of the Study

The current study sought to critically address the practice of rituals of distinction in nation-wide educational milieus to see if such practices can produce generations of underdeveloped and deprived learners. Data were collected over a course of two years from North Korea, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Somalia. A total of 419 teachers, educators and students from these countries responded to email communication, were observed through participant observation, or were interviewed through Skype; they provided descriptions and examples of educational settings and practices in their respective countries. The data were then analyzed qualitatively and in the light of (a) Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives, (b) Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and (c) Feuerstein's notion of ‘culturally deprived’ learners. It was concluded that, education systems in countries ruled by ideological or ideocratic regimes, intentionally and actively deprive learner generations of quality education with the aim of hammering whole societies into the shape which will guarantee their own grip on political power. Drawing on the concepts of 'small-c culture' and 'capital-c culture' from relevant literature, the paper argues that despotic regimes, by virtue of their education systems, mainly betray their most obedient citizens who are committed to them and whereby deprive them of true professionalism.

Education, as defined in the burgeoning literature since the 1940s, is supposed to be the path to the self actualization of learners. The job of education systems is to find each learner's main talent, and to provide the scaffolding the learner needs to nurture that talent into full blossomdefined as 'self-actualization' by Maslow (1943, 1968). Nevertheless, there are education systems in the world which do not seem to be working properly. The learners who are educated in such systems fail to develop into the stage of self-actualization which, according to Maslow (1943) and Berger (1994), is the ultimate goal of education. Based on insights from data, the current study will argued that, in countries where ideocratic/ideological regimes have control over curriculum content, they 'intentionally' move education systems into the direction which guarantees that learners will become obedient to the ruling power; it is further argued that, such educational practices deprive learners of true professionalism. The authors argue that, ideologically-aspired pedagogy--be it religious or otherwise--is doomed to create generations of underdeveloped citizens. The paper will specifically review relevant literature from the fields of education and educational psychology to generate its central hypothesis: that Feuerstein's (1990) individual-oriented notion of 'culturally deprived' learners can be extended to a whole society or a huge portion of it if 'culture' is redefined in terms of 'small-c culture' and 'capital-c Culture'.

As it was implied in the introduction, education systems in some countries (e.g., Japan, US, etc.) produce excellent results and professional graduates while they fail in certain other countries (e.g., North Korea, Zimbabwe, Somalia, etc.). A short-sighted explanation of why such a discrepancy exists would be to put all the blame on the learners and their capabilities. However, success in education is not a uni-variable issue. It requires only common sense to realize that, the success of any educational system is tied to a good number of variables one of which is the learner and his/her capabilities. Needless to say, concrete variables (e.g., infra-structures, buildings, technologies, textbooks, etc.) as well as abstract variables (e.g., educational ideologies, social and political perspectives, theocratic aspirations of political systems, etc.) work in tandem to decide whether an educational system will thrive and reach full blossom, or simply fossilize some way short of success. On this ground, the current study is important in that it sheds light on the kept-in-thedark side of educations systems in under-developed countries; it describes how political ruling systems intentionally deprive learners of the opportunities they need for self-actualization.

For the purposes of this paper, a brief review of some classic concepts in education is vital. Among other things, the current research will specifically build on Maslow's hierarchy of needs, Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives, and Feuerstein's notion of 'culturally-deprived' learners. These will then be merged to synthesize the main argument of the paper.

Although Maslow's hierarchy of needs is in essence a theory of psychological health, it can be brought to bear on theories of educational development in that it implies that the hierarchical fulfillment of innate human needs in order of priority will eventually culminate in self-actualization(Maslow, 1943). In other words, the basic premise of Maslow's theory is that, when individuals consecutively ascend the different levels within the hierarchy of needs and fulfill them one after the other, they may eventually achieve self-actualization and augment and explode their full potentials.

The most basic level in Maslow's hierarchy of needs includes physiological needs (i.e., food, water, sleep and sex). The next level includes safety needs (i.e., security, order, and stability). These two levels are important for the physiological survival of human beings (as well as other species), and people will not attempt to accomplish more and develop further unless these needs are fulfilled. Love and belonging comprise the third level of the hierarchy which is dependent on levels one and two. People will not share themselves with others unless they have already satisfied their basic survival needs. Once first, second and third level needs are satisfied, people will attempt to achieve 'esteem' which comprises level four; they will realize that, they need to be competent and recognized. When taken together, levels one through four are called Dneeds (or 'deficit' needs) in that any feeling of shortage in any of them gives people the feeling that they have to get them.

If they are satisfied, people will move to level five, or the cognitive level, where they feel the intellectual motivation to explore; needless to say, exploration is the gate to professionalism. If that is fulfilled, they will further move to level six which is an aesthetic level where they feel the need for harmony, order and beauty(Carlson, Buskist, Heth & Schmaltz, 2007) which are vital to the pursuit of knowledge; many modern technologies (e.g., aircrafts, spaceships, cell phone technologies, modern architecture, etc.) do require close attention to harmony, order and beauty. The fulfillment of level six will then move people to the last level, or the need for self actualization, where they achieve a state of harmony and understanding which results from their engagement in achieving their full potential (Berger, 1994). Self-actualized people focus on themselves and attempt to build their own (self-)image and selfconfidence, whereby they get ready to set and accomplish a goal. Higher-order needs (i.e., wholeness, perfection, completion, justice, aliveness, richness, simplicity, beauty, goodness, uniqueness, effortlessness, playfulness, truth, and self-sufficiency) are called B-needs or B-values(Maslow, 1968). B-needs cannot be fulfilled unless D-needs are satisfied first. Once B-needs are satisfied, individuals are able to develop a realistic selfimage and attain self-confidence.

Without a realistic self-image and an appropriate selfconfidence, no one will be able to rely on his/her own capabilities which are vital to scientific explorations and discoveries. Motivation for exploration is intricately tied to the explorer's self-image and self-confidence. In Maslow's view, self- actualized people possess innate 'metamotivation' which enables and motivates them to explore and reach their full human potential(Maslow, 1968). The implication of Maslow's hierarchy of needs for educational systems is that, if society and sovereignty do not pave the way for the fulfillment of lower-order D-needs, one cannot expect to see self-actualized people who will explode their full potentials in the society. This implies that, the political powers that rule different countries can intentionally manipulate the interconnections between Dneeds and B-needs so that individuals' self-images and self-confidence would not develop and they would not move in the direction of self-actualization which may eventually be corrosive to the ruling systems' grip on power.

Bloom's taxonomy aimed at classifying learning objectives. Dividing educational objectives into (a) cognitive, (b) affective, and (c) psychomotor domains, the taxonomy is hierarchical in the sense that learners' movement to higher levels is not possible unless they have already attained prerequisite knowledge and skills from the lower levels (Orlich, Harder, Callahan, Trevisan & Brown, 2004). The hierarchy motivates educational systems to engage learners in a holistic learning experience which encompasses all three domains(Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill & Krathwohl, 1956), and is supposed to be taken as a vital and foundational element in education (Shane, 1981).

The cognitive domain has to do with knowledge, comprehension, and critical thinking. According to Huitt (2011), the levels within this domain include:

The affective domain describes people's emotional reactions and consists of skills that determine how people feel others' pains and joys. The target is the growth and awareness of feelings, emotions, and attitudes. This domain too includes five hierarchically-ordered levels:

The last domain within Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives is the psychomotor domain (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill & Krathwohl, 1956). This domain includes a hierarchically-ordered set of skills which describes learners' capability to physically manipulate a tool or instrument. The levels of this hierarchy focus on development or change in behavior and skills. Although Bloom and his colleagues did not create any subcategories for this domain, Simpson (1972) proposed the following seven levels:

Bloom's view of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains has culminated in a stipulated definition of knowledge, a definition that involves the recall of universals and specifics as well as processes and methods (i.e., the recall of patterns, structures, and settings) (Bloom et al., 1956). As Krathwohl (2002) and Anderson and Krathwohl (2000) emphasize, Bloom's taxonomy of learning objectives has served as the backbone of many teaching philosophies--and specifically those that have to do with skills rather than content, because it envisages content as a vessel for the teaching of skills. It specifically relies on analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and creation to ensure that all orders of thinking are introduced to, and exercised in, students' learning--a way of practice that is absent in educational systems in less-developed countries. This implies that, ideocracies and despots can control content to make sure learners will or will not have access to certain skills, a point that has a direct bearing on the main theme of this paper.

Nevertheless, Bloom's taxonomy has been criticized too. Morshead (1965) leveled the first major attack against it by arguing that it was not a properly constructed taxonomy in that it lacked a systemic rationale of construction. Along the same lines, Paul (1993) called the sequential/hierarchical ordering of the skills in the cognitive domain into question. The latter led to a revision of the taxonomy which moved 'synthesis' higher in the order than 'evaluation', and reestablished the taxonomy on more systematic lines (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2000), which came to be known as the ‘Revised Bloom's Taxonomy’; it used verbs instead of nouns to label the levels of the hierarchy (i.e., Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating in that order). The revised taxonomy received critical acclaim by Paul and Elder (2004). All in all, educators unanimously agree that, learning of the lower levels in the taxonomy paves the way for the building of skills in the higher levels; this has a direct bearing on the Vygotskyan concept of constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978) which can be brought to bear on the main theme of this paper.

Beginning in the 1950s, the Israeli clinical psychologist Reuven Feuerstein achieved fame through his studies which focused on the techniques of boosting the intellectual ability of low-achieving children--whom he called 'culturally-deprived' through violent uprooting and poverty. His views ran counter to the dominant theories of intelligence of that time in that he suggested that, intelligence could be taught whereas other dominant theories of the time held that it was innate and fixed (Sharron & Coulter, 1994). He argued that, “without the foundation of a firm cultural base there is insufficient opportunity to develop the shared thinking and values that allow the individual to process information meaningfully” (Jarvis, 2005, p. 103). Adults select and present materials to children and explain and emphasize them. Individuals with firm cultural foundations are more likely to adapt to other cultures more easily, but individuals lacking any cultural foundation are not able to flourish anywhere (Jarvis, 2005, p. 103). The adult (called the significant adult, mediator, or mediating adult) mediates between the child and the environment, gives the environment structure, order, and meaning, and makes it possible for the child to internalize cognitive abilities alongside cultural beliefs and values(Sharron & Coulter, 1994). The significant adult, ipso facto his/her very existence and role, can provide--among other things--several types of mediation including (a) mediated focusing which helps children to develop perceptual and attentional abilities, (b) mediated planning which enables children to internalize ideas of routine and sequence, (c) mediated self-regulation which equips children with the ability to overcome impulsivity in favor of thoughtful planning, and (d) mediated precision which helps children to appreciate the importance of accuracy and precision (Feuerstein, 2003; Salmani Nodoushan, 2008a; Salmani Nodoushan, 2008b; Salmani Nodoushan, 2012; Salmani Nodoushan, 2014 Salmani Nodoushan, 2015a; Salmani Nodoushan & Daftarifard, 2011).

In Feuerstein's (1990) view, such Mediated Learning Experience (MLE) guarantees children's efficient cognitive functioning which includes effective thinking and problemsolving. He argues that, certain factors (such as collective Salmani Nodoushan, 2008a; stereotyped rejections or 'ideological othering', material and geographical barriers to access, extreme poverty, war, distinction, etc.) can hinder the development of efficient cognitive functioning. In his description of cultural 'difference' as opposed to cultural 'deprivation', Feuerstein argued that, cognitive abilities are tools of learning which are transmitted to learners when they engage in social interaction with significant adults(Jarvis, 2005). Although Feuerstein's views are highly reminiscent of Vygotsky's 1978 (1962, , 1981) social interactionism, they are not exactly the same. Vygotsky sees basic cognitive processes as innate and argues that, only higher cognitive functions are transmitted through social interaction, but Feuerstein argues--based on empirical evidence--that culturallydeprived learners not only lack higher cognitive functions but also lack fairly basic perceptual processes such as selective attention and visual scanning. As such, at the heart of Feuerstein's ideas lies the notion that human cognition can be hammered into given shapes, and it takes significant mediators to do this.

The brief literature reviewed has a direct bearing on the line of argumentation of this paper which seeks to argue that, ideological and totalitarian political systems intentionally uproot learners of their native cultures through ideologically-aspired education systems, and that this practice can produce masses of ideologically- deprived or ideocratically-deprived learners who fail to self-actualize or become true professionals.

This study was conducted over a course of two years between 2014 and 2016. For purposes of data collection, educational systems in five randomly selected lessdeveloped countries were targeted, and connections were built with teachers, educators, and students who could provide the researcher with descriptions and examples of educational ideologies and practices in the selected countries. Data were collected from North Korea, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Somalia over the course of two years (from 2014 to 2016). A total of 419 teachers, educators and students from these countries responded to email communication, were observed through participant observation, or were interviewed through Skype; they provided descriptions and examples of educational settings and practices in their respective countries. The data were then analyzed qualitatively and in the light of (a) Maslow's hierarchy of needs, (b) Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives, and (c) Feuerstein's notion of 'culturally deprived' learners. Table 1 display the composition of participants in the study.

Table 1. Participants of the Study

The qualitative analysis of the data obtained through interaction with the informants (i.e., educators, teachers, and learners) was done in the light of the brief literature review. The main finding of the study are presented as follows.

In the countries studied, where (ideocratic/theocratic/ ideological) systems rule, nothing is supposed to find the opportunity to challenge the grip of the rulers on power. It is quite reasonable to claim that, ideocratic/ideological regimes will do whatever it takes to remain in power, be it military, economic, political, or otherwise. The most important blessing which an ideocratic/ideological regime possesses is people's ignorance, and it will make sure to keep people ignorant all the time. When it comes to education, ideocratic/ideological regimes will make sure to change it into a system of memorizing controlled content (cf., Bloom's taxonomy level #1 or 'knowledge'). Such regimes control the content of what is to be taught in schools to make sure learners will not have access to certain skills which can motivate them to challenge the political system. Moreover, the process of teacher selection will also be controlled in such political systems so that learners will only have access to significant adults or mediators who are sure to implement what ideocratic/ideological regimes expect from them. Teachers in such systems are recruited through a selection process which heavily relies on their level of commitment to the ideologies of the ruling systems. Such teachers will not teach for creativity; they will at best copy the content of carefully selected course books into students' memories(Salmani Nodoushan, 2015c).

Seen in the light of Bloom's taxonomy, the results of the data of this study indicated that, in the countries studied, the ruling systems tacitly discourage learner's movement towards the higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill & Krathwohl, 1956; Paul & Elder, 2004). The participants of the study unanimously pointed out that in their countries--especially in North Korea and Zimbabwe- -textbooks and other course materials do not include tasks that require skills other than 'knowledge' and 'comprehension'; they indicated that the only exceptions are hard sciences like Chemistry, Biology, Medicine and the like. The participants in the study stated that, in their countries, sciences such as philosophy, theology, psychology, sociology, and other soft sciences are not encouraged, and that the content and tasks covered in such sciences are mainly kept at the level of 'knowledge' in terms of Bloom's taxonomy. Needless to say, a learner who is deprived of learning lower-level skills in Bloom's taxonomy will fail to find the way for the building of skills in the higher levels (cf., Vygotsky, 1978). Based on this, the pedagogy provided for learners in such contexts can be called the 'pedagogy of the oppressor' in that the ideological ruling system 'oppresses' the learners by depriving them of any opportunity which might otherwise help them to move towards higher-order skills.

Another finding of the study was that the systems of education in the countries studied in this research can be called systems of 'indoctrination' rather than 'education'. Although some educational philosophers may take indoctrination and education to be the same, there are vast but subtle differences between them. In fact, a muchdebated issue is if and how education and indoctrination differ. A good number of theorists favor the idea that education and indoctrination are distinct and that the latter is not desirable; there are, however, other people who believe that they do not differ in principle and that indoctrination is not intrinsically reprehensible.

Nevertheless, a common-sense distinction between the two is that education is the search for facts and the teaching of the truth while indoctrination is all about urging people to believe without questioning. Education aims at developing learners' ability to reason before accepting what is presented to them, but indoctrination aims at getting them to accept without reasoning. Education encourages disputes, doubts, and challenges, but indoctrination discourages them. While education aims at helping learners to develop their fact-driven and truthbased belief systems throughout the process of learning, indoctrination follows its own agenda of getting learners to embrace another person's beliefs (i.e., that of the ideological ruler), to completely and blindly agree with them, and to behave in accordance with them. The analysis of the data of the current study revealed that, 94.98% (i.e., n=398) of the informants who were contacted in this study argued that, educational systems in their countries could be referred to as 'indoctrination'. Only 5.02% of the interviewees (i.e., 13 interviewees from Pakistan and 8 informants from Venezuela) had some doubts and were not sure whether 'indoctrination' could be used to refer to educational systems in their countries.

Through indoctrination, bigoted ideological rulers (whose grip on power can be called 'ideocracy'-be it religious, fascist, Nazis, or otherwise) enforce political opinions, ideocratical beliefs, religious dogma, or even anti-religious convictions as educational agendas that aim to inculcate ideas, attitudes, cognitive strategies, professional methodology, and beliefs in learners(Snook, 1972). Indoctrinated learners are trained in such a way as to prevent them from questioning the information they receive or examining it critically. Indoctrination forcibly or coercively causes the learner not only to act but also to think on the basis of the ideological ruler's ideology and agenda (Harris, 2011; Wilson, 1964). It coerces learnerssubtly and unfairly but assuredly and unconsciously into internalizing the belief system expected, accepted and promoted by the ideological ruler(Dawkins, 2006). Needless to say, facts are the source of data which can directly support education, but indoctrination relies heavily on 'polarity' in language to sell its claims which encompass everything and leave no room for doubt or exceptions. Content analysis of course books and materials obtained from the participants in this study showed that, textbooks and course books used for indoctrination (especially the ones used in North Korea, Somalia, and Zimbabwe) are fraught with propaganda, logical fallacies, untested personal ideas, government-sponsored teachings and philosophies, and other forms of hand-picked fallacious information that can brainwash learners and hammer them into the shape approved by ruling ideological regimes. 95.7% (i.e., n=401) of the participants who were contacted in this study confirmed that, soft-science textbooks and materials that are used in their respective countries are mainly aimed at transferring 'knowledge' (defined in Bloom's terms) to learners, and that they mainly fail to move the learners to higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives.

Another difference between education and indoctrination is that the former gives room for different solutions to any given problem, but the latter rules out any kind of secondary thought and argues that there is only one solution to any problem, the one approved by the educational system of the country. Education is impartial, objective, unbiased, and founded in verifiable facts, but indoctrination is partial, biased, and ideologically-aspired. 76.61% (n=321) of the people contacted in this study argued that, course books and materials in sciences such as philosophy, sociology, and other soft sciences in their countries prepared learners to accept only one solution to any problem. Content analyses of the available materials confirmed their claims. However, they argued that in hard sciences, such as mathematics, different ways to attack a problem may be given in textbooks, and learners may be told that, a given mathematical problem, for example, can be solved in more than one way. All in all, the types of teaching described by the participants in the current study seem to inculcate baseless ideocratically-aspired beliefs in learners; they seem to be pedagogies that employ methods of instilling beliefs in learners--beliefs that they are not able to critically examine, question, or challenge. Table 2 summarizes the main differences between indoctrination and education.

Based on the information collected through email communication, participant observation, and Skype interviews with a sub-set of participants (i.e., 193 informants--61 teachers and 132 students from North Korea, Zimbabwe, Somalia), it can be argued that, a good example of the 'pedagogy of the oppressor' is what can be observed in North Korea, Zimbabwe, Somalia. Educator data could not be used since no educator from these three countries agreed to participate in this study (perhaps for fear of persecution). Data obtained from Pakistan and Venezuela indicated that, the situation in these two countries was much better. The 193 teachers and students from North Korea, Zimbabwe, Somalia were asked to provide concrete practical examples which could display a representative picture of the 'gimmicks' the oppressor uses in the educational system.

It was stated earlier that, Maslow's 1943, Maslow's 1968, levels of human needs are hierarchically ordered, and that moving to the higher level B-needs requires the fulfillment of the lower level D-needs. The first thing any ideocracy or ideological regime does on national scale is to keep the whole nation busy with basic-level survival needs; this is the situation in North Korea, Zimbabwe, Somalia. A huge number of the people work in multiple shifts and are yet unable to earn enough to support basic survival needs. A large percentage of the nation is below the poverty line and lives in utter destitution. Nevertheless, there are still many people who earn more than they need to cover their basic necessities. The ideocracy actively jeopardizes the safety and security of these people if they fail to conform to the ideology and aspirations of the ideological regime. They will be persecuted, threatened, and, if necessary, physically removed. One of the strategies/gimmicks that ideological regimes use blatantly and generously is what can be called 'ideological othering' which is roughly similar to what Bourdieu (1984) referred to as 'rituals of distinction' (Gartman, 1991; Feuerstein, 1990. Through ideological othering, people are labeled as either 'in-group citizens' or 'outlier citizens'. Those who are flagged as outliers, are considered 'aliens' (i.e., they are ideologically 'othered' or 'alienated'). They are actively uprooted of their social settings, and this is on a par with what Feuerstein (1990) calls 'collective stereotyped rejections' which can hinder their development of efficient cognitive functioning since, as Feuerstein argues, such people are culturally-deprived and will eventually lack higher cognitive functions as well as fairly basic perceptual processes--such as selective attention and visual scanning.

On the other hand, those who are considered to belong to the 'in-group' of the ideological regime are those who conform to the aspired ideology; the process of accepting these people in the camp of the ideological regime can be called 'ideological-selfing'. These are 'good' and 'obedient' citizens who receive what they wish as long as it does not create any threat for the ideological regime's grip on power. The bigoted regime is not worried about their sincerity or hypocrisy; the very fact that they have accepted or decided to pretend to conform to the bigoted regime's aspirations shows that they are always ready to trade their human dignity for material life. Nevertheless, even such people are kept within the realm of D-needs, in Maslow's (1943) terms, and are not allowed to move any further. They will not find the opportunity to follow their own cognitive, aesthetic and self-actualization needs. As such, systems of indoctrination practice their rituals of distinction within the first four levels of Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of human needs. As a conformist, the obedient citizen will nevertheless be given the opportunity not to self-actualize, but to actualize his/her 'self' after the model set for him/her by the bigoted regime. For instance, as a participant in this study clearly stated, the indoctrination system in

“[…] North Korea has set for itself the ultimate educational goal of ‘producing perfect human beings’ and the perfecthuman- being model to be copied by the learners is the supreme leader of the nation. Radio programs, newspapers, magazines, textbooks and course books, teaching materials, music, and even freeway billboards are gimmicked up with quotations from the despot's speech which permeates all aspects of life. He is the talking constitution, the talking law, and the talking regulations, and any resistance will entail intimidation, torture, life-imprisonment, or even death”. (North Korean teacher informant #4, email communication, 13th December 2015).

Another area brought under control by systems of indoctrination is the area of educational objectives. As stated above, Bloom's (1956) taxonomy of educational objectives is hierarchical in nature, and movement to higher levels in all domains is pending successful mastery of the skills required by the lower levels. As for the cognitive domain, learners in systems of indoctrination are rarely, if at all, allowed to move beyond the level of knowledge except in hard sciences.

“Hand-picked information is copied onto students by hand-picked, ideologically-charged, carefully-selected conformist teachers who discourage innovation and only transmit the hand-picked information to the students in a procedural manner within the milieu of the de-innovative system of indoctrination. Interaction is discouraged, and class time is dedicated to a unidirectional procedural transmission of information to learners. Assessment, too, does not go beyond the level of knowledge. Examinations, except perhaps in hard sciences, consist of questions that only ask for information, and the 'good' student is s/he who has memorized the content and is able to give it back to the teacher. Of course, this may not be true of hard sciences. In some fields, like medicine, chemistry, and mathematics, the system gives room to questions that pertain to the levels of comprehension, analysis, synthesis, application, and evaluation, but in fields such as philosophy, literature, law, history, sociology, and virtually any other area of humanities where moving beyond the level of knowledge is likely to create unexpected challenges that are potentially corrosive to the roots of the regime's power, innovation is discouraged, and maximum care is practiced to ensure learners' being stranded at the level of hand-picked knowledge”. (Somalian teacher informant #18, Skype interview, 29th July 2014).

This observation on the part of Somalian teacher informant #18 supports Perumal's argument that “. . . place shapes pedagogy and teachers' personal and professional performance and dispositions” (2015, 25). Teachers know that they are teaching ideologically-laden textbooks in an ideologically-incendiary setting, and they resort to selfcensorship (or epistemic avoidance). If they step out of the borders set for them by the ideocracy, their security will be in jeopardy (Maslow's level 2). Learners, too, are intimidated by the system so that they will not dare to challenge the system or they will be 'flagged' as unsuitable (or 'starred' as it is called in some countries), and will be dropped out of school.

Perhaps the affective domain is the area that comes under the heaviest covert attacks by any system of indoctrination. Learners' emotions, attitudes and feelings are cast into an ideologically-laden mold, learner differences are ruled out, and all of the learners are expected to be restructured into similar robot-like disciples of the bigoted ruler. Bloom's (1956) levels of the affective domain (i.e., receiving, responding, valuing, organizing, and internalizing) virtually boil down into at most two levels (i.e., receiving and internalizing) whereby the learner is made to 'receive' affect from outside and to internalize it as his/her own affect system--without any processing:

“We learn to accept that people are either with the preached ideology or against it; we also learn to adjust our emotions and attitudes accordingly. We learn to valuejudge others on this basis, and we even get ready to die for this cause”. (Somalian student informant #32, email communication, 1st January 2015).

Examples of this educational practice are the suicide bombers in the Middle East. This lends support to Milgram's (1963) study which concluded that, people are apt to commit atrocities if they are given orders by authority figures. Nevertheless, the affective domain requires certain provisions, and this is quite often achieved through ideological rituals. In Pakistan, North Korea and Zimbabwe, for instance, school children practice several episodes of ideologically-dictated rituals during a typical school day. Each school-day morning, before they go to their classes, they stand in lines for half an hour (to one hour) and repeat the slogans that are keyed to them by the specificallydesignated teacher whose job is to 'train' the students in accordance with the policies of the state. There is music, but it has been adjusted to the ideology pursued by the state. In Zimbabwe, Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 ("the Choral") has been recomposed and accompanied by an epic poem in the native language which aims at encouraging school children to revolt against the western world:

“It has become a ritual, and my classmates and I chant it twice during each school day. Class hours, too, begin with a few minutes of ideological speech, and we are made to hear and repeat certain hand-picked quotations from certain ideological figures (or to listen to micro-narrations about them) which we will have to remember for the next class session”. (Zimbabwean student informant #29, email communication, 7th April 2015).

Such quotations and/or micro-narrations are in fact 'actions' in that they can transform reality and can have certain social consequences > (Salmani Nodoushan, 2015b)(Tannen, 1989; Wittgenstein, 1953). They are used to structure students' affect in a specific direction. This observation resounds the claim made earlier that ideocracies can and will control content to make sure whether learners should or should not have access to certain skills.

The discussion presented hitherto leads to the main theme of this paper: that Feuerstein's (1990) concept of culturallydeprived learners can be extended to a whole society or a huge portion of it. Maslow's hierarchy of human needs and Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives were exploited in this paper to differentiate between education and indoctrination. Now it is time to focus on the main theme of the paper and claim that indoctrination will eventually create generations of culturally-deprived learners--who can be referred to as ideocratically-deprived or ideologically-deprived learners because they are the products of ideocractic or ideological systems. Needless to say, the authors are well aware that Feuerstein used the term 'culturally deprived' in relation to individual learners, but it can be suggested that an extension of the term 'culture' will allow the extension of 'culturally-deprived' to generations of learners, a whole society, or a huge portion of it.

In their definition of the term 'culture', educationalists quite often distinguish between 'small-c culture' (i.e., epistemic frames) and 'capital-c Culture' (i.e., the totality of all small-c cultures in any given society). In other words, the matrix in which the population of any given society lives is often called the capital-c Culture of that society which comprises many epistemic frames or small-c cultures (Salmani Nodoushan, 2009). Communities of people (e.g., lawyers, teachers, doctors, etc.) live within any society, and any of these communities has its own epistemic frame (or small-c culture) which controls its distinctive ways of doing, valuing, and knowing(Shaffer, 2004; Shaffer and Gee, 2005; Salmani Nodoushan, 2009). The way doctors act, value, talk, read and write, for instance, is informed by the way they think, and it is different from the way lawyers do the same activities because lawyers and doctors belong in different small-c cultures (Schon, 1983, (Schon, 1983, . This implies that, although people belonging to different small-c cultures within the same society belong in different epistemic frames, people who belong in the same small-c culture in different societies also belong in the same epistemic frame regardless of geographic boarders, politics, and so forth. As such, small-c culture can be redefined to include (a) any small-c which pertains to a single society (e.g., doctors in Germany), and (b) any small-butglobal- c culture which pertains to all societies regardless of borders (e.g., global-scale small-c culture belonging to all doctors in all societies and nations). This latter form of smallc culture can be referred to as 'small-g culture' (where g stands for 'global' but the lower-case typeface 'g' signifies its being a small-c culture albeit on a global scale). As such, small-g culture encompasses the totality of all the similar small-c cultures each of which belongs to a single society or nation--but when taken together collectively, they form a small-g culture(Salmani Nodoushan, 2009).

By the same token, we can think of a capital-but-global Culture (called a capital-g Culture) which encompasses all of the different small-c as well as small-g cultures from around the world. After all, there is only one race called the human race, and it is quite natural to talk of one human 'Culture' on a global scale. In our lifetime, we have witnessed the removal of internal geographic borders in Europe, and by the same token we can feel that the human race is doomed to unite into a global human nation under a single global constitution--and ruled by a single global political administration. It only requires common sense to argue that this is inevitable, and that it entails that education systems of the world should strive to make all citizens of the world ready to assimilate the hypothesized 'capital-g Culture' and to accommodate themselves to it.

Seen in this light, deinnovative oppressive systems of indoctrination are depriving huge portions of their societies of this global adaptation, and, as ironical as it may seem, they are doing this injustice to their most devoted and obedient citizens. Needless to say, nonconformist 'ideologically-othered' learners in systems of indoctrination are clever enough to know that they need to adapt to the 'capital-g Culture' in the end, and they aspire after and strive for that; they find the way out--for example, through brain drain or with the help of the Internet. Even if they remain (or are grounded) within the confines of their countries, they are cognizant enough to use proxy channels to make their cyber-emigration into their relevant 'small-g Culture' through the Internet and other social networks. It is the conformist and obedient portion of such societies that fails to see this pressing need and fails to reach out for the vital adaptation. It is this portion of the society which is 'Culturally-deprived' (or ideocratically deprived) in the context of the global 'small-g Culture'. As such, systems of indoctrination are changing portions of their societies into under-developed learners whereby allowing for the extension of Feuerstein's individual-oriented concept of culturally-deprived learners to a whole society or portions of it. This is the way in which a system of indoctrination mass-produces generations of 'small-g- Culturally-deprived' learners, and because ideocracy is the cause of such deprivation, the afflicted learners can be referred to as ideocratically-deprived learners.

In this connection, it is also vital that we re-define 'professionalism'; in a traditional sense, a professional was the individual who was familiar with the small-c culture of his field in his homeland society (Salmani Nodoushan, 2009). If we accept the redefinition of small-c cultures as small-g cultures (explained above), we will need to redefine 'professionalism' too. Seen in this light, professionalism can no longer be taken as familiarity with society-specific smallc cultures; rather, professionals are people who are not only familiar with their local or national small-c cultures but also with the global-scale small-g cultures of their professions. This suggests that systems of indoctrination are not only deinnovative but also prevent people from growing into true professionals who are familiar with small-g cultures of their professions on a global scale. As such, indoctrination is enslaving, not emancipatory (Salmani Nodoushan & Daftarifard, 2011).

From a sociological perspective, indoctrination systems are conducive to a situation which Freud (1937) called 'identification with aggressor' (also known as the 'Stockholm syndrome') in which the oppressed (i.e., the obedient portion of the society) unconsciously adopts the perspective of the oppressor or the abuser--to ward off the anxiety induced by the indoctrination system. In fact, the learners, in the pedagogy of the oppressor, are the captives and the oppressive indoctrination system is the captor. Drawing on an unconscious defense mechanism, the captives unconsciously work in tandem, and create an emotional bonding, with the conscious captor to protect their under-developed 'selves' from hurt and disorganization. Due to its dehumanizing nature, an indoctrination system prefers to intimidate rather than educate. In such anxiety-prone systems, the 'identification with aggressor' mechanism ensures that the abused/oppressed learner is metamorphosized into an oppressor in the end, and this cycle goes on(Goleman, 1989). The most obedient learners' fear will change to relief when they resort to this kind of defense mechanism (i.e., when they identify with their oppressor). Nevertheless, there will also be 'ideologically-othered' learners who will become righteously indignant; the latter group (which has already been referred to as 'starred' or 'flagged' learners) will be dropped out of school. Needless to say, such 'identification with the oppressor' eventually culminates in a grotesque educational situation in any society.

This paper argued how systems of indoctrination betray their most loyal and obedient believers by turning them into what was referred to as ideocratically-deprived learners. The paper established connections between Maslow's hierarchy of human needs, Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives, and Feuerstein's individualoriented notion of culturally-deprived learners to expatiate on its own main theme: that redefining small-c cultures in terms of small-g cultures can reveal how systems of indoctrination can turn the whole, or portions, of a society into culturally-deprived learners who fail to become globally-recognized professionals in the sense defined in the paper. The study found that in ideocratic/ideological systems of education:

The argument presented in this paper lends support to Perumal's (2015) argument that place can shape pedagogy, and that teachers' professional and personal performance and dispositions are also controlled by place. It also supports Tuan's (2001) contention that place can be taken as the starting point for the articulation of cultural meaning and awareness, and that it is also central to human emotional attachment. The argument of this paper also suggests that, from a critical-pedagogical perspective, ideological power plays a major role not only in creating and defining place but also in defining and shaping learners' and teachers' statuses within place. It suggests that ideologies/ideocracies practice their power and dominance by inscribing them in place, and that this can determine and control the destiny of individual learners and teachers who live within the place.

Based on the argument presented in this paper, it can be recommended that, obedient people should be awakened from the complacency with which they are living in societies ruled by ideocracies. The paper takes side with Gruenewald (2003), Halsey (2006) McLaren (1997), and Page (2006) in suggesting that, critical pedagogies of place are needed, and also that systems of indoctrination which ignore the impact of place on learning and teaching need to be reformed (Somerville, Davies, Power, Gannon and de Carteret, 2011). It lends support to Haymes's (1995) contention that pedagogy should resist 'marginality' and 'territory' whereby emancipation from oppression can be guaranteed. All in all, the paper suggests that, people in less-developed places need to be awakened to the fact that systems of indoctrination are colonizing and exploiting their most obedient citizens both mentally and physically, and that this needs to be challenged.

This study was based on data obtained from a limited number of countries where despots or ideological regimes control the content and processes of school curricula, and shape and structure teachers. Moreover, the study was limited in terms of the number of people who participated in it. The method that was used for data analysis was qualitative. As such, the findings of the study cannot be generalized to all other less-developed countries of the world. Any global-scale generalization of the findings will definitely require a lot of other quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies to be conducted in different regions of the world and with many more participants and informants.