Knowledge Harvesting: A Deep Probe Into Organizational Values

Abstract

This paper describes a methodology for harvesting knowledge within a professional development workshop in a large organization. Knowledge harvesting is a process aimed to [0 document every possible contribution of every participant, and {ii} arrange that documentation into an indexed summarized representation. The product of knowledge harvesting creates a deeper understanding of what people know as individuals and harness that knowledge into the continuous growth of the organization. A well documented product of a professional development workshop can lead to plan future activities, re-examine values and beliefs, surface organizational challenges and serve to re-adjust relationship between values and practices. Literature [Argyris & Schon, 1978; Senge, 1990] suggests that organizations tend to be plagued with internal conflicts between their stated beliefs and their actual practice.

Keywords :

- Knowledge Management,

- Concept Mapping,

- Knowledge Harvesting,

- Collaboration,

- Collaborative,

- Decision-Making

Introduction

This paper presents a model attempted at diminishing the gap between what organizations do and what they say. The model is based on a guided, collaborative effort, involving the organization's members in identifying (i) gaps between belief and practice, [ii] the effect of these gaps on organizational goals and spirit, and (iii) planning methods of compensation. The process is based on knowledge visualization, using collaborative concept mapping and large group collaborative decision—making called “ThinkClick” (Yaniv & Crichton, 2008]

Defining the Problem

The realization that educational organizations (schools, teacher colleges and teachers certification programs, school boards, etc.) are conflicting between their educational beliefs and their everyday practice has haunted this author since the day he was expelled from high-school at the end of the 10th grade. Trying to shake off the trauma of being expelled, the author has been reflecting on his own role and trying to understand his teachers‘ and the school's role in paving a failure path for a capable student. Working with schools, academia and educational organizations have deepened this author's realization that universal humanistic values etched on every school doorway are shattered by reality and the need to produce quantifiable measurements needed by external systems like governments, boards and academic institutions.

The value of “collaboration" can be taken for example. is there an institution today that will not state “collaboration" as one of its highest organizational values? Collaboration is a sacred humanistic value. It encompasses the idea that people should strive to live in harmony with each other, respect each other, and complement each other. Collaboration is the corner of human activities that actually lead to and underpin the notion of peace.

Some examples of statements about collaboration on schools‘ motos as collected from their websites are given:

“...common values are articulated in a virtues oriented environment that encourages responsible citizenship and collaboration.” Brentvvood School, Calgary 1

“...educate students is one that respects the individual and his/her right to be treated with kindness and acceptance in a cooperative atmosphere. Competition is limited, creativity is encouraged and collaboration is valued for students and adults...” Little B. Haynes Elementary School, East Lyme, Connecticut 2

Sveiby and Simons (2002) report results from a survey they have conducted on 8277 subjects and state that “collaborative climate is one of the major factors influencing effectiveness of knowledge work” (p. 420). This finding is crucial as it stands in apparent conflict with the interests of the individual member - ‘should I give up my own need to be better, so I will be working for a better organization‘?

So why is it that in most years of public education we foster competition?

Is school fostering competition? Of course the sports teams, debate teams, high stakes testing etc do so. The most common idea of schooling is competition - the better your grades, the better are your chances in life to excel.

Do educators realize the conflict between their values and practice? Do they understand how so many classroom activities foster competition?

They might, but it's well hidden. The next argument will attempt to explain this phenomenon, as we are talking about a committed population of people who embrace reflection as a part of their professional life.

The most trivial reason is reality. Behaviouristic or based on the authors’ previous dichotomy of educational philosophy ‘knowledge oriented‘ practices have been accepted as legitimate practices since the beginning of schooling. The most trivial conflicts between values and practice were easy to identify (like corporal punishment as a form of negative reinforcement) and have been abolished in most cultures long ago. But some practices are hard to identify as conflicting to humanistic values. These practices (like marks and grades, and prizes and competitive tasks) are well etched into everyday's practice and are not standing out as the corporal punishment. The fact that these practices are endorsed and sometimes demanded by the administration of all levels helps to legitimize them as value-based practices.

A study conducted by Rhodes, Neville and Allen (2004), reports 40 facets of possible job satisfaction or dissatisfaction like work load, proportion of time spent on administration, student behavioural issues etc. None related to frustration due to the personal values vs. required practices.

One potential explanation can be found in what psychology defines as ‘Defense Mechanisms‘. Without an elaborated inquiry into Freud's psychoanalysis a simple explanation would define ‘defense mechanisms‘ as personal, unconscious strategies that help us deal with conflicts that cannot be resolved by us.

Amongst Hefner's (2002) list of defense mechanisms, the two that can be applied in our attempt to explain the results of the above mentioned study (Rhodes et al, 2004) are ‘denial‘ - “arguing against an anxiety provoking stimuli by stating that it doesn't exist" or ‘intellectualization‘— “avoiding unacceptable emotions by focusing on the intellectual aspects".

Teachers know and they “pay" for it. They pay for it in frustration and diminished job satisfaction as shown by Lloyd Yero, in her book Teaching in Mind (2002). Yero states that the conflict between values and practice results in frustration, stress and dissatisfaction. The author can add, from his own observations, two different cultures (Israel and Canada), that it causes a sense of lower self efficacy (e.g. who am I to fight the system?!) and higher levels of unresolved cognitive dissonance (e.g. what are my own values and/or how do they connect with the education system).

How does the organization pay?

Higher levels of dissatisfaction and frustration lead to increasing numbers of teachers leaving the profession, increased work place absences, increased sick leaves and poor atmosphere in the schools. lngersole (2001) reports in a study of statistical sample of 6733 US teachers that the problems of school staffing are related to factors other than teacher retirement. The main, proposed remedy to teachers‘ turnover is “improvement in organizational conditions" (p. 24). Both lngersole (2001) and Rohdes et al (2004) identify the need of teachers to participate in the development and ongoing informing of school policies.

The Knowledge Harvesting process described in this paper, involves teachers, as equal partners, in the process of improving organizational integrity, or in other words: bridging the gap between the organizational values and its practice. While teachers are the participants described in this paper, it is important to note that this process has been used successfully with other organizations.

Definitions and Functions

What is Knowledge?

“Knowledge is a fluid mix of framed experience, values. contextual information, and expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information. It originates and is applied in the minds of knowers. In organizations, it often becomes embedded not only in documents or repositories but also in organizational routines, processes, practices, and norms" [Davenport & Prusaki 1998, p. 5).

What is Knowledge Harvesting [KH)?

Knowledge harvesting [KH] is a relatively new concept. It is defined as the process of transferring organizational knowledge from tacit, informal, unorganized state to a formal, accessible and usable state. KH is an emerging field related to Knowledge Management, adding to the idea of “inventorying" knowledge, the idea of seeking of the organizational “spirit", trying to identify the main themes that form and identify the organization and its goals.

Why Harvest?

Some of the most valuable knowledge resources in any organization are informal. They are what Agrysis and Schon [1978) call organizational memory: “For organizational learning to occur, ‘learning agents‘. discoveries, inventions, and evaluations must be embedded in organizational memory” [Argyris and Schon, I978 p.l 9). Knowledge resources, are scattered in individual members‘ brains, composed of experiences. interactions, excitements, values and beliefs, passion, sense of mission, identity, pride ... They are so entrenched in the actions and everyday practices of the group members that they simply disappear into practice

In some cases, as demonstrated in the above mentioned surveys (lngersole, 2001; Rohdes et al, 2004), the most crucial themes are hidden behind defense mechanisms. making the main organizational themes extremely hard to identity. This phenomenon contributes to a total misunderstanding of the main challenges the organization is facing in implementing these themes. Knowledge of collaboration will help to explain the above statement with an example, If 'collaboration' is stated amongst the organization main themes (as a goal] but competition fostering practices are common, an attempt to identify themes within this organization might leave 'collaboration' undiscovered.

This paper suggests that by probing deep into organizational themes and reading between the lines can help identifying the organization's “souI", helping in improving organizational atmosphere and members‘ satisfaction, helping to achieve organizational real goals.

Challenges in construction of a Knowledge Harvesting model

Knowledge “...originates and is applied in the minds of knowers" (Davenport & Prusak, I998, p. 5]. It is fluid and tacit and in the mind of knowers... it is influenced by individual perception, values, and state of mind. Consequently, when queried about personal view and opinions about education or the school, a frustrated teacher is likely to be influenced by his/her frustration.

First Challenge: Seek for the truth

The first challenge is then probing for real and honest contributions while being aware of personal biases and temporary state of mind.

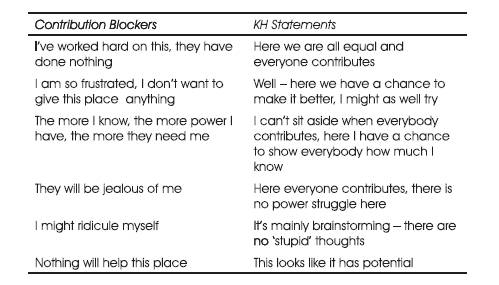

Second Challenge: Get people to contribute

During 30 years experience of observing teachers, in both formal and informal settings [classrooms and staff rooms], and within international contexts (Canada. America, and Israel) this author observed the following statements as universal:

- “I've worked hard on this, they have done nothing"

- “I am so frustrated, I don't want to give this place anything"

- “The more I know, the more power I have, the more they need me”

- “They will be jealous of me”

- ‘‘I might ridicule myself"

- “Nothing will help this place"

Teachers realize and recognize the need to contribute for the good of the whole. They probably preach to their students every day. On the other hand, teachers are people, who also have their personal agendas, their sensitivities, and their histories of disappointments. Therefore, a challenge is finding respectful and safe channels of communication that will minimize the effects of personal interests and emotional history and re- energize the individual's need to contribute.

Third Challenge: Get people to think critically

The most difficult challenge of all is to get many teachers to realize that some of the “truths” they cite as their educational philosophies tend to be nothing more than institutional slogans. While quite a controversial statement, the author based this on his observation of responses from a personal philosophy survey (Zinn, 1990) that he had asked his graduate students in the Faculty of Education to complete.

Zinn (1983) constructed the Philosophy of adult education inventory (PAEl] presenting educators with a list of questions like: in planning an educational activity, I am most likely to clearly identify the results I want and develop a program [class workshop] that will achieve those results: assess learners‘ needs and develop valid learning activities based on those needs, etc.

Based on 75 questions, the survey calculates a score for each five educational philosophies: Humanistic, Radical, Progressive, Behavioristic and Academic. In the author's own work, he tends to classify these philosophies into two categories as, Human Oriented (the first three) and Knowledge Oriented (the last two).

Many of the author's students have reported that they scored high as holding both humanistic values and behaviouristic values. This “hybrid" philosophy, mixing ‘people oriented‘ philosophies (like progressive, radical and humanistic) with ‘content oriented‘ philosophies (like behaviouristic and academic)shows a misunderstanding of the essence of humanistic values. Teachers could be unaware of the inner conflicts between values and practice and make statements like “learner centered"; “inquiry”; “collaboration”; “intrinsic motivation” without committing themselves, while practicing activities that foster the opposite values like full control over the learning process, assigning competitive tasks, rewarding and punishing students as means of reinforcement, etc.

The challenge here is the need to verify what are the real beliefs and values teachers hold even when they faced the conflicts between what they state and what they do.

Facing this challenge will pave the road for the next phase of the model working with the organization and its members on bridging the gap and compensating for conflicting practices.

Forth Challenge: Get people to be creative

As presented before, when faced with highly loaded moral challenges people might fold and adapt defense mechanisms like denial or intellectualization. That state- of-mind is not conductive when the need (as in this case) is inspired, passionate, “out-of—the—box" thinking if the people are to be expected to give their valuable contribution for organizational growth

Fifth Challenge: Provide a safe environment for honest encounters

People should feel safe. It is safe to assume that an honest discussion can be risky if sensitive issues are to arise. This challenge requires the full collaboration of the administration and sometimes even administration-free meetings.

So far, this paper presents a need; A need (focused on an educational organization) to help members to bridge the gap between what their organization states its values are and the practices it embraces.

Why is it important for an organization to bridge the gap?

Ethics: An organization should be very clear about its values and stay loyal to them.

Function: The way the organization functions will be improved by increased awareness to potential gaps between values and practice and preventive or compensation measures can be employed.

Internal Collaboration: It will increase as people will need less defensive measures to hide behind.

Growth: An organization will grow into a learning organization, empowered by the collective knowledge of its members.

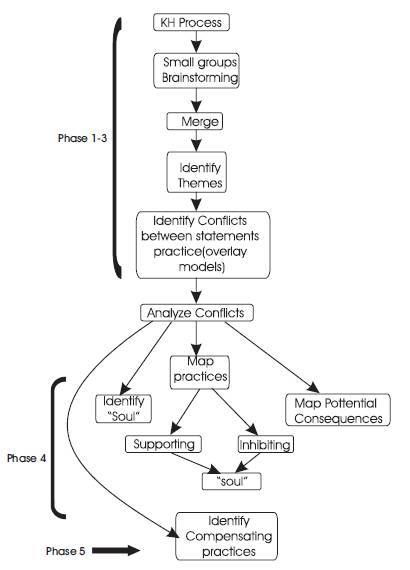

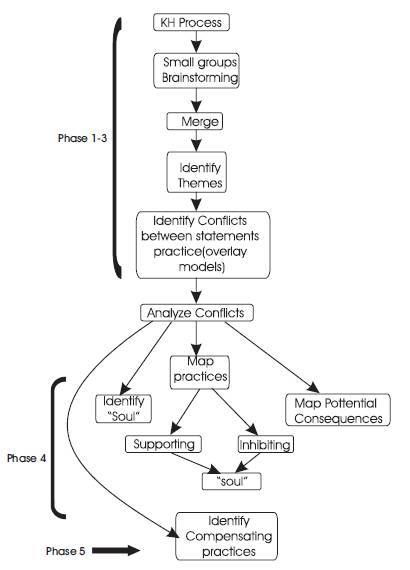

Now, that the needs have been laid out, and hence a model is proposed (Figure l ). The KH process is suitable for small or large groups (e.g. a work team of four people or a large workshop with hundreds of participants). When applied online in large organizations, it can serve even thousands

Figure l. Know-Deep: A model for knowledge

Phase One: Small Groups Brainstorming

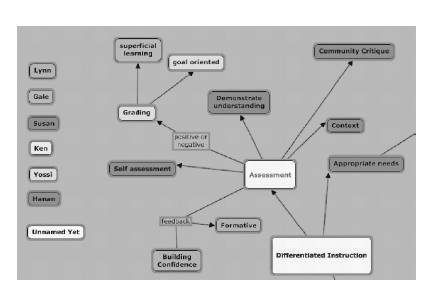

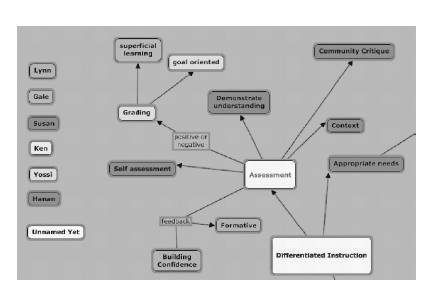

The process starts with small groups in different rooms or sitting around tables in a large hall. Each table has a moderator and a 'mapper' (an external trained knowledge harvester]. The mapper uses a computerized concept mapping tool (e.g. cMap Tools which is highly recommended because of its collaborative nature). Each mapper has a projector or a large screen showing the evolving map. The process of mapping requires a preparation step in which all group's participants are recorded on the session's map with an identifying style (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A group's map ready for input

Once the map is ready, the groups are assigned a topic for brainstorming. The topic is one of the issues the organization is interested in exploring.

Figure 3. A segment of a group‘s brainstorming map on the issue of diflerential Instruction

Figure 3 is a segment of one group (of the many groups) map. As the map materializes on the group's screen people continue talking, commenting on the mapper's interpretation or accuracy. The map is continually modified throughout the process.

Because of the visible nature of the KH process, as individual contributions are identified, the map serves each member as a real time monitoring device of his/her own performance within the group which requires extensive research into team dynamics and personal awareness. This point will be discussed in the conclusion and future research sections ahead.

Phase Two: Merging Small Group Maps Into One

Using Cmap Tools allows a 'Super-Mapper' to merge all the small groups’ maps into one while avoiding redundancies. The Super-Mapper identifies the contributions of each small group in a similar manner to the one used in Figure 3 to show individual members‘ contributions, while losing the individual members‘ identifications. This map is developed in a central place, visible to all interested, so each member can see how his/her own contribution is embedded within the small group's contribution and then, ultimately, as the small groups contribution is considered into the large map.

Phase Three: ldentify Themes

The mappers, coordinated by the 'Super—Mapper' are then assembled and organize the combined map into themes. An example of a theme that stems from the Figure 3 is ‘self assessment' as it repeats in many of the Small groups‘ maps.

The node ‘self assessment' and other themes are linked to form a more generalized theme like: ‘Allow students to take responsibility for their learning‘. These themes are forming the ‘Themes Map‘. The ‘Themes Map‘ becomes the desired outcome for the first three phases.

Phase Four: ldentify and Analyze Conflicts between Values and Practice

This is the most challenging phase of all. The Mappers, guided by the Super-Mapper, examine each theme and try to identify the relevant practices. In some cases, the Super—imposition of a model is helpful. In this case, dealing with educational philosophies, a good reference might be the work of Zinn (1990].

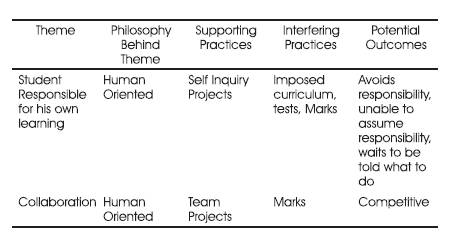

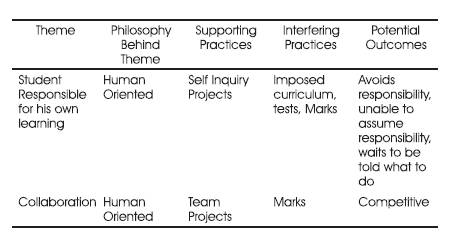

The outcome of this phase is a table of themes and the Practices that either support or interfere with them. Table 1 is an example of such themes.

Table 1. Values [Themes] Vs. Practices and potential outcomes

The table will make the spirit of the organization [or the 'Soul'] apparent: In this case [as predicted by the author, would be the case of many educational organizations], a Human oriented philosophy will be dominant. This identification, based on a collaborative process in which all organization's members have been involved can serve as the ethical foundation for the next phase of the process i.e., identification of compensating practices.

Phase Five: ldentify compensating practices to minimize the gap between Values and practice

Table 1 serves as the foundation for another gathering of all organization's members in which they are asked to Work on a list of activities that can bridge the gap.

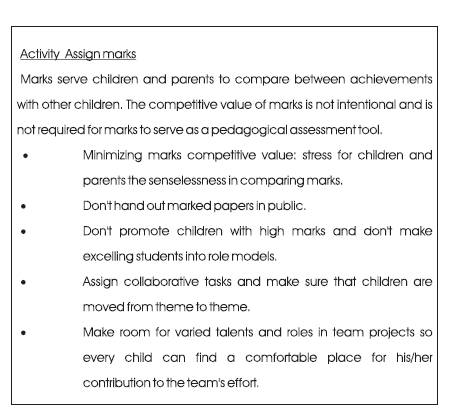

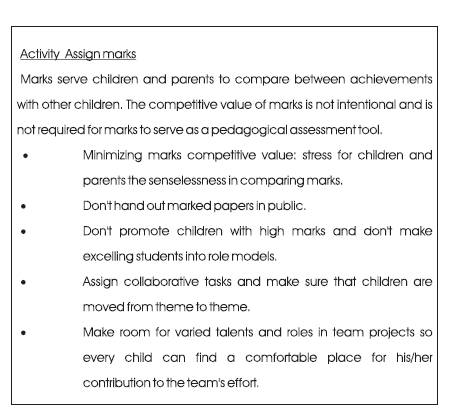

Again, they are assigned to small groups and each group Is assigned with one theme to work upon. Here is an Example of the task and a group's product for the theme 'Collaboration':

The Task

Brainstorm classroom activities that can foster the value 'Collaboration' and activities that foster competition, suggest means to minimize the competitive influence of practices like 'marks' and stress the value of collaboration. The group's product (just a segment of it):

The product of the day can be a document and/or website listing all gaps and proposed compensating Activities.

Follow-up

In order for this process to leave a mark on organizational behaviour, a scheduled activity should be embedded into future professional development sessions. During these activities, members will report and document new compensating practices they have been practicing, stemming from the previous KH phases. These practices will be amended into the organization's formal knowledge site.

Discussion

Is this model an answer to the challenges presented before?

There are three major principles that are built into this model that should help address whether the KH process is a suitable answer to the challenges confronting organizations:

Principle One: Collaborative Process of Knowledge Construction

Principle Two: Visual Mapping to allow non-linear thinking and homogenous interaction

Principle Three: Encouragement for each member to be an equal partner in forming [what might potentially become the organization code of ethics.

First challenge: Seek for the truth

If the first challenge has to do with personal biases and state-of—mind, the process of engaging each member as an equal in an activity that might change the organization atmosphere can resolve some of the dissonance described above. Sharing in this mission offers a fertile ground for personal biases and agendas. The visible contribution of each member encourages the members to take an equal share (or more].

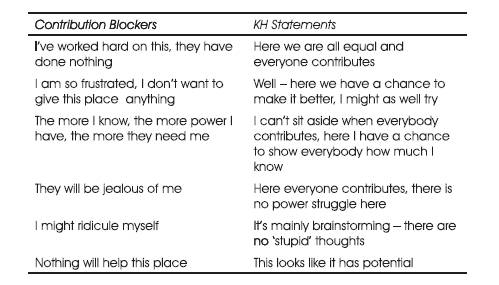

Second Challenge: Get people to contribute

The following table shows the potential in people attitude shift due to the KH process.

Third Challenge: Get people to think critically

The process and examples guided by the mappers tend to get people to rethink their practice, re—evaluate their values and share in the search for bringing their organization to a level closer to their beliefs. Theme searching using concept maps has been demonstrated with the research on Cognitive Flexibility Theory (Jacobson & Spiro 1995). The contextual links across topics and issues are making themes recognition simpler.

Fourth challenge: Get people to be creative

The fact that brainstorming is mapped on a non-linear medium, makes thought unbound by articulated language structures and opens up room for associative thought. Burst of ideas, recorded collaboratively, serve to trigger more ideas that trigger more ideas. People trigger each other.

Fifth challenge: Provide a safe environment for honest encounters

This process cannot be addressed by this model. The only hope is that if the organization's leadership is willing to engage in KH together with their people it will generate the suitable atmosphere for a fruitful start.

Table 2. Potential shift in people's willing to contribute

Conclusion

The model described in this paper has been tried twice so far. The first application (Yaniv & Crichton 2008) was in a conference of international development projects leaders. The second application is still in progress within a professional development workshop of a large urban school board. It is showing very promising data.

Research is needed to examine many of the issues raised by the model:

- How is team dynamic effected by real time exposition of all contributions?

- How are people reacting to this form of collaborative process?

- Does it help them overcome the challenges described above?

- How are organizational goals modified if at all?

- Does the process generate momentum of change? and

- How long does itcontinue?

Additional components are worked upon for large audience decision-making processes (using iPhone and iPod Touch technologies as input devices) and knowledge collection and management tools to automatically index voice and video recordings.

Notes

1http://www.cbe.ab.ca/schools/view.asp?id=56

2http://www.eastlymeschools.org/page.cfm?p=177

References

[1].Argyris,C., &Schon, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Sydney, Australia: Addison—Wesley Publishing Company.

[2]. Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working Knowledge [electronic Resource]: How Organizations Manage What They Know. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

[3]. Heffner. C. (2002). Ego Defense Mechanisms. AllPych Online. Heffner Group. Retrieved April 27, 2008, from http://allpsych.com/psychologyl Oi /defenses. html.

[4]. lngersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher Turnover, Teacher Shortages, and the Organization of Schools. Center forthe Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington.

[5]. Jacobson, M. J., & Spiro. R. J. (1995). Hypertext learning environments, cognitive flexibility, and the transfer of complex knowledge: An empirical investigation. Journal of Educational Computing

[6]. Rhodes, C.. Nevill, A., &Allan, J. (2004). Valuing and supporting teachers: a survey of teacher satisfaction, dissatisfaction, morale and retention in an English local education authority. Research in Education (71), 67-80. doi:Article.

[7]. Senge, P. M. (T 990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of learning organizations. Toronto, Canada: Currency and Doubleday.

[8]. Sveiby, K. E., & Simons. R. (2002). Collaborative climate and effectiveness of knowledge work — An empirical study. Journal of Knowledge Management‘, é[5], 420-433.

[9]. Yaniv, H. (2008). ThinkTeam — GDSS Methodology and Technology as a Collaborative Learning Task, in Adam Fredric, [Ed.), Encyclopedia of Decision Making and Decision Support Technologies, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, In Print

[10]. Yaniv, H., Crichton, S. (2008). ThinkClick — A Case Study of A Large Group Decision Support System (LGDSS], in Adam Fredric, (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Decision Making and Decision Support Technologies, IGI Global, Hershey,PA, In Print

[11]. Yero, Judith Lloyd (2002) Teaching in Mind: How Teacher Thinking Shapes Education. Hamilton, MT: MindFlightPublishing

[12]. Zinn, L. M. (1983). Philosophy of adult education inventory [PAEl). An assessment tool used to identify personal philosophies. Boulder Co: Livelong Learning Options.

[13]. Zinn, L. M. (1990). Identifying Your Philosophical