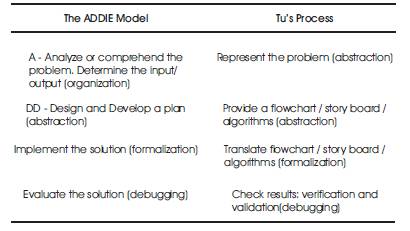

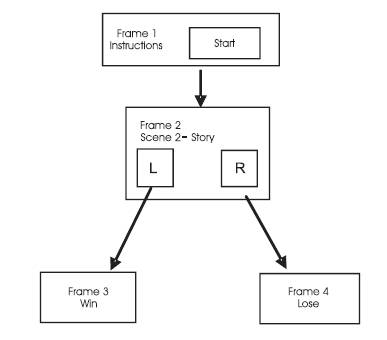

Table 1. A comparison of the ADDIE model with Tu's Process.

Several studies have demonstrated that games have been effectively used as an instructional strategy to motivate and engage students. This paper presents the use of the process of game development as an instructional strategy to promote higher order thinking skills. An analysis of the various aspects of game development including graphics, narration, game play and game programming and their relationship to higher order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis and evaluation is discussed. Experiences of instructors and students from two summer camps support the claims of the analysis.

Higher order thinking skills involving analysis, synthesis, and evaluation are critical for success in modern, technological societies. The concept of higher order thinking skills was put forth in Bloom's Taxonomy, which includes both lower and higher order thinking skills as distinct phases in cognitive development. Lower order thinking skills enable a student to deal with existing information, whereas higher order thinking skills enable a student to analyze and create new bodies of knowledge from existing knowledge, and evaluate this newly constructed knowledge.

A sound instructional strategy must help students to transition from lower to higher order thinking in acquiring knowledge. Several strategies and tools such as concept maps (Canas, Novak, 2006), graphics organizers (Ellis, 1999) have been developed to encourage and foster higher order thinking skills. Several studies have demonstrated the use of technology in particular to foster and promote higher order thinking skills maps (Coley, Cradler, Engle, 1997; Kafai, Ching, 2001; Ringstaff and Kelley, 2002). Game play or use of serious games designed to teach specific topics (Prayaga, 2008) is a fairly new instructional strategy and shows promise in improving student motivational levels, engagement and descriptive capabilities< (Howard, Morgan and Ellis, 2006; Klassen and Willoughby, 2003; Reiber, 2005). The purpose of this paper is to make the case for the use of game development vs. game play, a relatively new use of technology in classrooms, as an instructional strategy to foster higher order, abstract thinking.

The rest of this article contains a discussion of the various aspects of game development, and a case study in the use of game development activities to foster higher order thinking in K-12 students. Specifically, the activities and contributions to higher order thinking of developing game graphics, game narrations, game play sequences, and game programming are described. A pilot study involving elementary, middle and high school students in a twoweek summer camp further illustrates how the activities associated with game development foster high-level, conceptual thinking. The article concludes with a discussion and lessons learnt.

Game development is a multifaceted, multidisciplinary activity which requires skills in the development of graphics/visualizations, narration/story line, audio effects, character development, and game play. The combination of tasks and activities that are brought to bear in the design and implementation of games promotes the development of more abstract cognitive processes that entail higher order thinking. The remainder of this section considers each of these aspects of game development in turn.

Developing appealing graphics is possibly the most essential element of game development. In the broader context, well-constituted graphics can convey information in a concise, comprehensible way. Graphics create visualizations which can be highly effective in conveying an idea. It is well known that humans are largely visual creatures. Throughout time humans have used pictures to communicate difficult concepts quickly and effectively. Generating graphics is in a sense a creative activity. “Creative thinking is generally considered to be involved with the creation or generation of ideas, processes, experiences or objects” (Saskatchewan Education, Chapter IV). In this regard Urban (2004) suggests that when students create a website on how to use a Powerpoint, it is an application of higher order thinking skills, specifically in this case it is synthesizing. Extending this idea to a gaming environment it can be said that when students create graphics and other game assets for their games, they are using analysis (analyzing color schemes to match the mood of the game), and synthesis (synthesizing the different components that have to be blended together to create a cohesive design).

Writing a narration or a coherent story line is a complex task. At the very least writing a story line requires good communication and expression, describing the various characters and their relationships, and conceptualizing the flow of action or plot as the narrative unfolds. Recognizing that a story has a logical beginning, middle and ending requires critical analysis that is typical of abstract thinking.

Narration or the story line of a game sets the theme and context for the game which can determine the motivational levels during game play (Dickey, 2006). In order to write a game script, the writer must first decide on the genre of the game, and then analyze the plot and the story line he/she wishes to follow. The process requires that the writer maintain logical relationships among the different elements of the script, and the interrelationships among the various characters. Game development companies spend large quantities of money to hire writers to accomplish this task. This activity can potentially be quite daunting and challenging for students, especially so for those in elementary and middle school grades. Yet as the pilot study described in Section 3 will illustrate, young students were highly motivated to develop game narratives, and were able to carry out this complex task successfully.

Developing game narrations requires that game developers integrate information in many formats including textual, audio and graphical. Game development, through its multiple facets, such as visualizations, story boarding, and or audio formats can help individuals to express ideas which might be more difficult to express through just plain text narration. The Center for Applied Research in Educational Technology (CARET) suggest that an important aspect of learning is the ability to integrate words and imagery. This same sentiment is also echoed by Mayer (2001) who states that "When both words and pictures are presented, learners can engage in selecting images, organizing images, and integrating words and images". The process of systematically combining words and images into a coherent story requires critical analysis, problem-solving and evaluation that are typical of higher order thinking.

Game play is the heart and sole of game design and development. The user interactivity, character choice and relationships, win/lose conditions, rules of the game, and game theory (conflicts in the game and conflict resolution strategies) are just some of the aspects of game play about which the developer must make decisions (Waraich, 2004; Zagal, Nussbaum, & Rosas, 2000). Game designers and developers have to analyze several alternatives in strategizing their game and then they must make choices from among the alternatives. Numerous ideas must be synthesized to present a coherent, well thought out, and consistent medium of entertainment. Creating an experience that immerses the player of the game in a world of fantasy that remains sensible and believable is a challenging cognitive task.

Programming is what makes all the planning and design come alive. In this phase, game developers make decisions regarding the specifications and requirements for the game, resolve all design issues, carry out the coding processes, and perform testing and maintenance procedures. Use of logic and structure are heavily emphasized during this phase, necessitating the application of all the higher order thinking skills. Thinking about algorithms and procedures requires sustained reasoning and use of problem solving strategies that are needed both to complete a specification or requirement and to resolve errors in coding. This is the stage where ideas of iteration, control structures and repetition all of which require analysis, synthesis and evaluation will be used extensively to get the code to work.

The processes of “organization”, “abstraction”, “formalization”, and “debugging” (Perkins, 1981) in software development are strategies that are applicable to problem solving in general (Tu and Johnson, 1990). In turn, such processes may be employed in order to systematize game development. The ADDIE model, which is primarily a generic model for instructional design, has all the attributes of a general problem solving strategy and can be applied to game development as well. Table 1 presents a mapping of the relationships between Tu's process of problem solving and the ADDIE model.

Table 1. A comparison of the ADDIE model with Tu's Process.

Table 1 serves to illustrate that problem solving requires the use of higher order thinking skills (analyze, synthesize and evaluate) and how they are promoted specifically in computer programming. The ADDIE model was used as a game development methodology in a pilot study on game development that is described in the next sections. The following sections describes the methods used in the study and presents some results regarding the relationships between game programming and higher order thinking skills in elementary and middle school children.

In the summer of 2007, the University of West Florida offered a single summer camp for two weeks for students from area elementary and middle schools. In the summer of 2008 the demand for the game programming camp was so high that a total of three camps were offered. Data in this study is from the camps in 2007 and 2008. During the camp, students learned a variety of techniques and built several complete games. The remaining sections contain accounts of the student population, software used in the camp, methodology used in the camp, the study itself, and results that were attained.

The basic goal of the pilot project was to increase student awareness of the types of processes and planning that go into technical development projects, and particularly as they might pertain computer science. The ultimate goal was to encourage students to look at computer science as a possible discipline that they could pursue in their higher education. Students were invited to participate in the camp through pamphlets sent to the schools. Some of the students were recommended by their teachers and others were registered directly by their parents.

Students who participated in these camps were between the age groups of 10 to 16 years. A total of 21 students in 2007 and 23 students in 2008 participated in the camps. A total of seven girls and 6 African American students were included in this sample. Most students were from local public middle and high schools. The software used for the camp was Adobe Flash. Flash was the best choice since it is a relatively simple yet a comprehensive tool for game development. It allows the user to create graphics and animations, and also to write the code, all in the same integrated development environment.

The duration of the camp was three hours per day for two weeks. During that time, each student completed several animation sequences and three games. The games fell into three categories: Adventure games, arcade style games, and puzzles. The introduction of technical content, which comprised increasingly sophisticated techniques leading to the creation of the games, was designed to challenge students while not being so fastpaced as to lead to failure. Students started by making movie clips and animations. Then they learned how to create buttons to provide interactivity.

After this groundwork, students created an adventure game from materials and templates provided by the instructor. In this activity, students were introduced to program code that controlled the game. Their first task was to associate the code with the buttons to create the game. After this step, students created a second adventure game which they built on their own. Subsequently, students completed an arcade style game and a puzzle game. The largest majority of students succeeded in performing all of the game development activities described in this section.

Week one activities included learning to create movie clips, animations, buttons and simple goto statements. equipped with these tools students could create adventure games. Week two activities included learning advanced concepts such as collision detection, a very important element of game development, and the use of dynamic variables and timers in games to keep track of scores for the player within a specific time period. Students created the arcade style games and puzzle games by the end of week two. At the end of the camp, students filled out a satisfaction survey regarding their experiences in the camp. Activities and results of these efforts are described in subsequent sections.

The following sections contain descriptions of observations made during the camp as they pertain to the various aspects of game development.

In the study it was clear that when students were instructed to design an adventure game, they used visualizations in very clever ways to communicate and express their ideas. Examples of innovative visualizations included hiding hints behind objects in the game, camouflaging hints to match the terrain of the game so the hints were not easily visible, providing alphabets that could be dragged and dropped to make new words, and using a pattern to hide the hints. See examples of some games posted on the following http://www.uwf.edu/lprayaga/Summercamp games/index.html that illustrate the creativity, ingenuity and motivation of students in designing these games. Use of techniques like collision detection, array manipulation, dynamic variables is not simple; they are used by senior game developers and researchers of educational games to promote higher order thinking skills through exploration. As the students implemented these processes in their games, they spent substantial amounts of time thinking or analyzing through the activity of designing the visualizations.

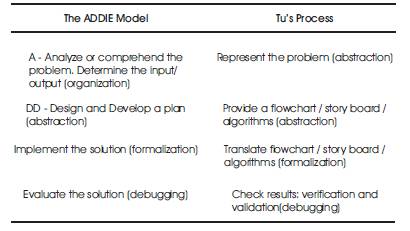

As stated in the methods section, students started designing their games from the templates they had been provided. Although they all started at the same place, they demonstrated that their imaginations were fertile, wild and vivid since all the students significantly extended the original template, and developed very different designs for their games. Students in the camp were so motivated by the gaming environment that they typically wrote three to four pages of text describing their story with a pencil and paper. The level of concentration on the task and the amount of work performed was quite impressive. Another interesting fact was that while the template game had a maximum of 10 to 15 frames, some of the students in the camp designed games which included 100 to 165 frames. This level of activity suggests that the game development environment has substantial utility to motivate students to employ higher order thinking skills. See examples (figure 1 and figure 2) of story boarding/flow charting that demonstrate how a gaming environment through the element of narration helps students to develop such skills.

Game play, as mentioned earlier, is where elements of the game including the rules of the game, the win and lose conditions, and the time intervals within the game are determined. These activities essentially require the designer to maintain a logical flow between various aspects of the game. It is in this phase that the designer mentally visualizes the game and thinks about the various possibilities for the hero, villain, and non playing characters. Additionally, the designer must conceive of the various scenes in the game and resolve any conflicting situations within them. Students in the summer camp were required to write a story line including the goals of the game, rules of the game, and the win/lose conditions of the game. Students had to employ higher order thinking skills in these tasks since they had to provide an analysis of the game through their write up on the goals of the game, synthesize the various activities in the game, and determine the win and lose conditions.

Good game development and programming promotes the use of higher order thinking skills by requiring the use of a variety of problem solving strategies. Students employed the ADDIE method as described in Section 2.5, to develop and provide a written analysis of their game. They used the method to determine the inputs and outputs, to design and develop their written ideas, and to present an abstraction of their game. They then implemented the flowcharts with real code and finally tested and evaluated the game. Students exceeded the expectations of the camp organizers with regard to both the complexity and coherence of the games they were able to produce.

Figure 1 shows a very simple flowchart that was provided by the instructor to illustrate the use of this representation and to let students know what should be done in the game. It has 3 levels of depth. The sample flowchart was used simply to provide a pictorial representation of what needs to be programmed in the game. Example, clicking the start button takes you to frame 2, clicking the L button takes you to frame 3 where the player wins and clicking the R button takes you to frame 4 where the player loses. Students then transferred this logic to the design of their games. This was presented as an example of the basic decision structure that is applied to all games.

Figure 1 A basic Flow Chart from an Adventure Game

Figure 2 shows a flowchart created by a student. This one is much more complex than the one from which they started. The flowchart in Figure 2 has nine levels of depth. As each subsequent level was added, the student had to keep track of what was happening in the previous levels and synthesize the new ideas in the new level with the older scenarios. Failure to account for the flow of events at previous levels can lead to a clash between levels or even cause the game to crash. These activities clearly show the use of problem solving strategies in a game development environment that would generalize to other technical tasks.

Figure 2. A Complex Flow Chart for the game (F represents the frame number and the triangles represent buttons)

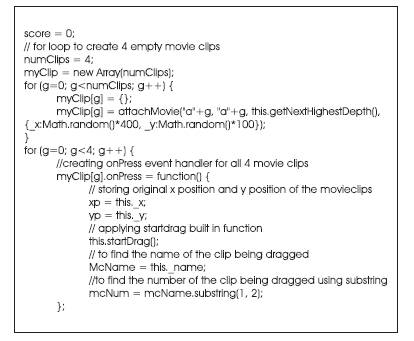

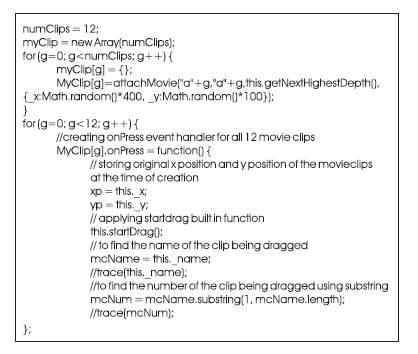

Figure 3 illustrates a typical segment of code with which students worked. Students were able to make modifications to the code and see how the modifications affected the behavior of the game. Students were not afraid to experiment with the code in order to get it to do what they wanted. The Code example in Figure 3 was part of the template for a picture puzzle game with 4 puzzle pieces. The students quickly wanted to expand the code and found where they had to change the code, (see colored lines in the example) and changed it. They tried it with 6 pieces, some with 9 pieces and others with 10 and above.

Figure 3. A typical code segment with which students had to work

Students who experimented with fewer than 10 puzzle pieces had no problem, they quickly changed the number of pieces from 4 to 6 or 8 etc in the code, but those who tried it with 10 and more pieces immediately flocked to the instructor disappointed. The problem was that the code was written to account for fewer than 10 pieces, and not designed for double digit numbers. We not only had to change the value of the variable numclips from 4 to whatever double digit number the students wanted to have for their puzzle, but also had to change the naming convention followed for the movie clips stored in the array to accommodate the double digits. We quickly made the code adjustments reflected in Figure 4 to have it work for double digits. It was clear that the gaming environment prompted the students to approach the teacher to help them learn rather than allowing the students to wait passively for the teacher to teach them.

Figure 4. The corrected code segment.

In this study, young children, with little concept of the technical challenges they would face, carried out logical, methodical, complex thinking, typical of higher order thinking as described by Bloom. Furthermore, they thoroughly enjoyed it. The survey at the end of the summer camp was not mandatory, so not all students participated in it. Some of the questions from the two surveys in 2007 and 2008 are reported here. Of the 15 students who participated in the survey in 2007, 13 students reported that they would like to take more computer science courses to become good programmers and design computer games, 2 students reported no. Of the 16 students responding to the survey in 2008, 13 responded that they would like to come back in 2009 for a game camp, 3 indicated that they might be interested, and none of the participants stated that they would not want to return. An analysis on the data collected from the summer camp suggests that students were very motivated by the gaming environment. Over the course of the camp they:

? turned in an average of 3 to 5 pages of written story lines

? provided flowcharts, typically with four to six levels of depth

? were very creative and innovative in using the design and code

? wanted to extend the code given to them demonstrating that they were in control;

The process was one in which the students actively sought to learn rather than relying on the teacher to teach. It is clear that students found the tasks engaging.

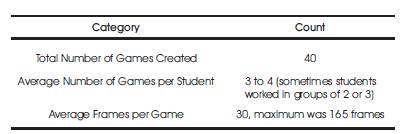

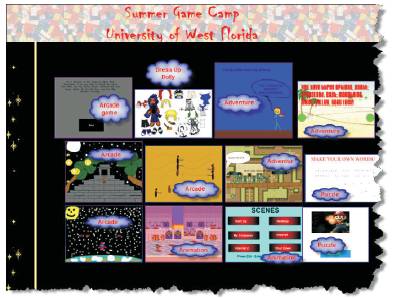

Table 2 contains data on the productivity of the students during the two-week camp. The total number of games produced were about 40, students spent on average, 2 to 3 days per game, a concentrated effort. Figure 5 shows the sample games created in the summer camp. The average number of frames per game, 30, indicates that students created games of substantial complexity.

Table 2. Student Productivity Measures

Figure 5 Sample games created in the summer camp

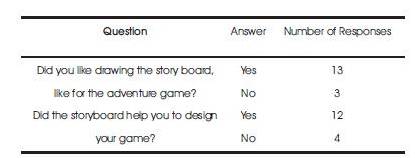

In 2008, instructors wanted to introduce students to the importance of design before coding since this would help students learn, (1) to have a broad picture of their project (game), and (2) debug, which are critical aspects of good programming (Sleeman, 1986, Tu, 1990). This was a major lesson learned during these camps. In 2007, the instructors did not require students to have a design document prior to development, and that resulted in a lot of time spent by the instructor in debugging student code. Including the design aspect in 2008 provided the instructor and the students with a blue print that they could compare the game to and use for debugging as necessary. As in Table 3 on student attitudinal measures, students enjoyed the process of planning for the games. Instead of tasks that required higher order thinking being considered burdensome, students perceived such tasks as enjoyable. Additionally, students saw the value of planning, in that the large majority thought that the storyboarding process helped them to produce a better game. Students are often reluctant to develop outlines for papers they must compose in literature classes. Methodical, advance planning of this nature is often viewed as an unnecessary burden. In the context of game development, similar preparatory activity was viewed both as valuable and enjoyable.

Table 3. Attitudinal Data Pertaining to Systematic Design (N = 16).

The most striking result of this study was how far the students went beyond the expectations of the camp planners. It is clear that the development of games, even though a time-consuming, technical process that requires significant attention to detail, was highly motivating to the students. Both the quantity and quality of the deliverables that students produced were substantial. The games that the students produced were quite detailed, particularly considering the ages of the students involved in the study. It is clear that the participants produced their games as a result of careful planning, analysis, implementation, and evaluation of the earmarks of higher order thinking.

It is also interesting that even though the students were young, they learned, adhered to, and mastered a rather detailed methodology for game development ADDIE. The ADDIE model was a very effective strategy for students to follow in the development of their games. This model provided them with a framework that helped them to focus their thoughts and ideas and translate those ideas into a game demonstrating that young students can methodically execute a detailed process, analyzing their progress along the way. Another beneficial result of the use of the methodology was that students had a good lesson in the benefits of planning in the execution of a motivating task: building a game.

Game program development is viewed as holding good potential to cultivate the type of thinking skills that will increase success and retention in technical fields. Its particular similarity to software development, the need to create and analyze requirements and design, and then to implement the result, will foster success in technical programs. While more work remains to be done, the results of these game camps and the pilot study would suggest that game development is an activity that holds great promise to encourage higher order thinking skills.