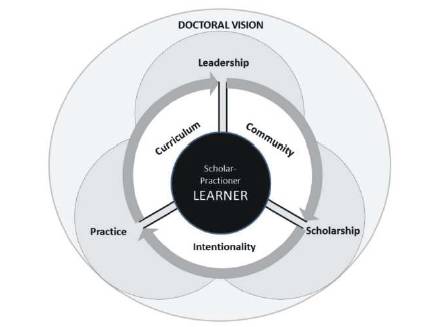

Figure 1. Doctoral Learning Model. This Figure Illustrates Key Components (leadership, practice, scholarship) in a Mutually Interactive Doctoral Learning Community

While doctoral education is well-established in traditional academic environments, the role, value and function of online doctoral education is less clear. Interwoven with concerns about the online delivery format is the changing focus of doctoral education. As a function of social, technological and economic pressures, doctoral programs are expanding the traditional emphasis on basic research to include more integrated, applied models of inquiry. Understanding the unique needs and educational objectives of a scholar-practitioner model shifts concerns about online doctoral education from an emphasis on mode of delivery to an awareness of how the mode of delivery aligns with the broader learning model. The issue is not online or face-to-face, but rather rests in alignment of the theoretical model with development of curriculum and academic support structures. This paper highlights specific strategies and theoretical approaches underlying the creation of a doctoral online learning model focused on maintaining academic excellence while adapting to meet the needs of modern learners.

Doctoral education has a long, well-established history in the academic environment. Stereotyped by visions of the traditional research emphasis with established teachers and professors leading groups of eager learners through a complex, daunting exploration of the philosophical foundations and theoretical possibilities of their field, doctoral education has always emphasized the learning experience as a function of the totality of the academic environment. Extending beyond credit hours, classroom experiences or assessments of knowledge, doctoral education highlights the interactive, immersion of the learner into the academic and professional community. The key to the traditional model is transfer of knowledge to the next generation of scholars. Up to now, this doctoral culture has served well, but changes in our modern society, driven by rapid advances in educational and communicative technology, are challenging the classic vision of doctoral education. The proliferation of online education and the launching of doctoral programs into this method of delivery have prompted reflective questions about what it means to be a doctoral learner. Specifically, can online education prepare doctoral learners in a manner accepted by the academic environment?

Online education has been plagued with concerns about the validity, effectiveness and quality of student learning outcomes. Despite a plethora of research establishing the equivalence between learning gains available via online or face-to-face education (see http://www. nosignificant difference.org/, Russell, 2010, for a comprehensive discussion of the issue), many still question the value and relevance of online learning. Inherent in this challenge is the assumption that online learning should mimic face-to-face learning; that the values, nature and purpose of an online education should be equivalent to that of a traditional program. But the same technological and social forces that provided impetus for the growth of online education simultaneously shaped the demands, nature and characteristics of the learners seeking these “new” online degrees (frequently referred to as professional or scholar-practitioner degrees).

Learners now demand educational experiences that are not only mobile and flexible, but degree programs that integrate professional experience within the context of the theories, ideas and methodologies espoused by traditional academia (Servage, 2009). While this trend holds across the spectrum of post-secondary education, the impact is most noticeable at the point of the online educational journey receiving the most scrutiny: doctoral degree programs. An examination of online penetration rates (proportion of institutions offering an online equivalent to a face-to-face program) shows that doctoral programs (12.4%) lag far behind their bachelor's (29.9%) or master's (43.6%) equivalents (Allen & Seaman, 2005).

Institutions of higher education begrudgingly came to accept online learning as a viable means of teaching the basic terms, concepts and theories of undergraduate education. Close behind, institutions catered to the demands of professionals pushing for practitioner-oriented masters degrees offered online as a means to accommodate the hectic schedule of the working adult. In times of economic uncertainty in the United States, these programs flourished as a means of enhancing the credentials (and economic potential) of the middle class. Yet, held sacred throughout this transition was the doctoral degree. While professors acquiesced to the value of online education at the bachelor's and master's level, resistance remained to hold sacred the pinnacle of academic achievement.

But, perhaps, concern about online doctoral degrees is not about the method of delivery, but rather rests in hesitations over expanding the meaning of a doctoral degree. Traditionally, recipients of doctoral degrees served as the predecessors to institutions of higher education (Golde, Jones, Bueschel & Walker, 2006; Nyquist, 2002). Acceptance into doctoral programs was restricted to the academically elite due to the finite number of academic positions available in the academy. Those with newly minted doctoral degrees were young scholars ready to begin the slow steps through the promotion and tenure ranks of higher learner. Key to this journey is scholarly activity directly tied to the creation of knowledge; as such, the focus has been almost exclusively on discovery as the basic empirical skill set imparted to doctoral candidates.

While the academy undoubtedly continues to need stewards of practice to sustain traditional research and academic positions (thus ensuring the continuing existence of traditional doctoral education), our rapidly changing, modern society has created a demand for a new kind of scholar (Servage, 2009). Adapting to social, technological and economic pressures, there is an increasing need for a new doctoral model emphasizing application of knowledge in concert with creation of knowledge (Boud & Tennant, 2006; McWilliam, Taylor, Thomson, Green, Maxwell, Wildy, & Simons, 2002).

The need for more applied doctoral degrees is not a debate unique to online learning; recognizing the exclusively empirical scope of the PhD, various derivatives have been developed to designate a less research-focused degree format (e.g., EdD, DBA, DNP). Simultaneous to the social emphasis on the need for scholar-practitioner model was an increase in educational and communicative technology that supported more flexible forms of higher education delivery (Leners, Wilson & Sitzman, 2007). As such, a natural synergy developed between online education and the working professional. The demands of the workplace for applied, research knowledge coincide with an educational modality that allows one to maintain their current professional position while pursuing advanced study (McWilliam et al., 2002). As such, experienced, working professionals have the opportunity to enter online doctor programs with an eye towards developing scholarship for impact in practice (Wellington & Sikes, 2006). Not surprisingly, these forms of applied doctoral degrees are growing (Maxwell, 2003; Neumann, 2005; Scott, Brown, Lunt & Thorne, 2004) and are among the early adopters of the online format.

Recognizing this shift, the key to breaking down bias and resistance to online doctoral degrees rests in an understanding of the philosophy behind practitioner-based doctoral programs and the learning organization that supports the integration of professional experience, advanced content knowledge and scholarly investigation. The strong growth in online doctoral programs targeting working professionals (Lee & Nguyen, 2007; Servage, 2009) mandates a better understanding of the similarities (Scott, et al., 2004; Neumann, 2005) and differences between traditional and applied models of doctoral education. Golde, et al. (2006) describe the opportunity to identify differential outcomes for doctoral education, moving beyond the narrow emphasis on knowledge-production to encompass a more comprehensive view of the value of integrated, applied research. The issue is not one of superiority (i.e., a comparative rating of the relative value of online or face-to-face doctoral programs), but rather lies in identifying the unique components of an online, scholar-practitioner doctoral program that ensure academic quality.

With an awareness of the unique, applied goals and perspectives of professional adults pursuing advanced degrees, the doctoral vision of a scholar-practitioner program is four-fold

This vision of doctoral community extends traditional views of doctoral education with an emphasis on increasing opportunities for working professionals to join the doctoral community, generating and disseminating applied research, and encouraging an expanded definition of scholarly engagement throughout the academy. Achieving this vision requires a comprehensive understanding of the learning model required to strategically foster academic, professional and scholarly success for doctoral students in online programs.

As highlighted in our model of doctoral education, see Figure 1, the doctoral learning community is a mutually interactive entity driven by the doctoral vision. Within this model, doctoral learners engage in a reflective, recursive process driven by three overarching intellectual goals: (i) leadership, (ii) practice, and (iii) scholarship.

The elements comprising the learning model continually interact to form an interdependent whole. Viewed operationally, the model represents a paradigm for the study of the existing knowledge of various disciplines and the creation of new knowledge (scholarship), the application of this knowledge through contributions to the workplace and society (practice), and the ability to create methods to exert positive influence in organizations and communities (leadership).

Practice, leadership and scholarship are both the core and the driving force of the new paradigm of online doctoral education (Servage, 2009). Supporting this core are three vital, mutually reinforcing pre-conditions

Figure 1. Doctoral Learning Model. This Figure Illustrates Key Components (leadership, practice, scholarship) in a Mutually Interactive Doctoral Learning Community

Unlike previous academic experiences, a doctoral degree is a lengthy, self-directed pursuit requiring extended motivation, self-efficacy and purpose. The issue of self-directed motivation and intentionality becomes even more prevalent in the online environment which is void of the social components of face-to-face education. As such, deliberate emphasis and support for intentionality is essential for fostering the success of learners entering an online doctoral program.

As soon as learners express an interest in pursuing a doctorate degree, the university begins a dialogue of increasingly focused questions that are designed to help gauge the learners' intentions and their willingness to work and to learn. From their initial contact with prospective learners onward, enrollment advisors go to great lengths to set proper expectations with respect to the rigors of doctoral learning. This new appreciation of the doctoral journey requires a self-directed, intentional approach; one that is a qualitative leap from their past educational experiences. To be successful, incoming learners must adjust their sights to these expectations, which coincide with the perspective all doctoral learners should adopt when embarking on their course of study. According to Walker, Golde, Jones, Bueschel and Hutchings (2008).

Too many students approach doctoral education as if it were a continuation of the prior sixteen to eighteen years of schooling, with the student as the relatively passive recipient of the knowledge ladled out by faculty members, and success measured by correctly completing well-defined assignments in a fixed timeframe. Instead, doctoral students must be active managers of their own careers, purposefully charting a course and asking for what they need, while remaining open to new ideas, input, and opportunities heretofore unimagined. (p. 116)

Enrollment advisors work with prospective learners to encourage a deeper examination of their motivations and understanding of the commitment necessary to attain their goals. Learners continue to reflect on their intent and begin articulating their understanding of the scholar-practitioner model throughout activities, assignments and experiences integrated throughout the curriculum.

The first three classes are viewed as a progressive process of clarification by learners of the expectations of a doctoral program of study. Through various learning opportunities and conversations, the learner and the doctoral program are simultaneously determining if the relationship is a good fit. The goal of the initial class sequence is for learners to effectively engage in the educational process, model doctoral demeanor and demonstrate ownership of their journey and needs. At this point the intentionality of the learner and the demands of the program should be clear, with a clearly conscious decision on the part of the learner to engage in the program of study.

Aligned with traditional, face-to-face models of doctoral education, the curriculum of online doctoral education emphasizes a scholarly approach to investigation and knowledge. The difference therefore lies not in the topic of investigation or the scientific rigor of the inquiry, but rather in the targeted integration of professional experience as a key foundation of the intellectual pursuit and, most obviously, in the mode of interaction. In addition, curriculum sequencing (and the related support) is structured with an awareness of the unique needs of working adults who are re-engaging with the academic environment after an absence due to career obligations.

Recognizing that doctoral learning is a developmental process, the curriculum must be structured to support iterative growth toward the broader intellectual and scholarly program goals. In addition, the curriculum (including developmental perspectives, expectations and benchmarks) must be clearly articulated to learners, faculty members, and support associates. For the purposes of illustration, we highlight two focal points in operationalizing curriculum considerations: the program entry sequence and dissertation process.

The program entry sequence represents the initial request by learners for information though the first year; the remainder of the program is viewed as a progression of increasing rigor across research and dissertation development, scholarly writing, content knowledge, and leadership. At the core of the scholar-practitioner model is an appreciation that working professionals can rise to the opportunity of education and performance. There is an understanding that learners enter with professional experience, maturity, and a deep intentionality towards knowledge and the application of knowledge. They are driven by internal motivations to engage in learning that is relevant, realistic, and rigorous. As such, learners thrive on curriculum emphasizing the construction of knowledge and its relevant application (see Merriam, 2008 for a comprehensive overview of leading theories and key principles of androgogy). Curriculum expectations must parallel students' intentionality, by monitoring the relevance and rigor of doctoral learning activities.

To achieve the desired outcome of creating an excellent academic environment in which learners can grow, a vital component is the expectation of a progressive, ever-increasing performance on the part of learners. This movement from the opening program sequence to the third-year qualifying experience should culminate in self-accountability and self-directed learning and research. As Walker et. al. (2008) indicate, the formation of scholars occurs over time, through iterative learning and the meeting of consistently increasing expectations. To facilitate this growth, the curriculum must integrate a framework of ever-increasing benchmarks of performance for learners along the dissertation journey (Jones, 2010). Ultimately, across the faculty, learners, and support staff, clarity in the requisite reading, scholarly writing, analytic skills, and leadership development needs to occur. Benchmarks for graduates must be clearly defined, assessed, and documented, and they must be qualitatively different for a beginning first-year, second-year, and third-year learner; this type of curriculum transparency is vital in providing structure to complete the dissertation (Tluczek, 1995; Mah, 1986). The balance between simple retention and the retention of learners capable of demonstrating increased self-direction and learning is vital. Through a guided multi-year curriculum, learners will master the ability to develop learning and analytic methods to demonstrate self-development intellectually, emotionally, and socially.

Not to dismiss the value and importance of traditional doctoral education models emphasizing scholarship aimed at theoretical advancement, the new culture of doctoral education raises the value and importance of applied work and the role of the doctoral learner in utilizing their scholarly knowledge in practice (Servage, 2009; Wellington & Sikes, 2006). Curriculum decisions must be structured to: (i) maximize learners' intentionality via a curriculum that fosters the integration of professional experience with scholarly knowledge; and (ii) foster the creation of knowledge as it occurs in a social exchange. Through this type of scaffolding with deliberate emphasis on the interactive nature of learning within a community of professionals, learners will be given an opportunity to demonstrate an increasing repertoire of skills and knowledge as scholars, practitioners, and leaders.

This interdependent model emphasizes the role of practitioners in development of leadership competency. By participating in classroom dialogue, researching the peer-reviewed literature of their disciplines, and integrating application-based knowledge, learners expand their leadership understanding and translate classroom learning into effective application. As such, the role of community – highlighting the important role of both faculty and peers – is essential for effective learning in a practitioner-oriented program.

At the heart of the scholar-practitioner model is the appreciation of faculty, directors, and associates as knowledge workers. As highlighted by (Senge, 1990), learning organizations are places “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together” (p. 13). Embracing this view, it is essential for faculty to engage in their own professional development in order to actively create excellence in doctoral learning. Faculty members enter the online classroom as accomplished subject-matter experts with significant professional experience, knowledge, and skills; they understand how to learn and appreciate the need to continually develop their knowledge and facilitative skills. In addition, unique to the scholar-practitioner model is the professional experience that each learner brings to the classroom. As such, not only are the faculty content experts, but learners also contribute knowledge, skill and expertise to advance the intellectual climate (Floresh-Scott & Nerad, 2012). To build (and maintain) the scholarly community, it is essential that programs retain faculty members who are engaged, dedicated to learners' success, and are self-directed in their constant search for learning opportunities and performance feedback (Mutsuddi & Mutsuddi, 2008; Pedler, Burgoyne & Boydell, 1997). Likewise, programs must also incorporate avenues for interaction and collaboration that highlight the professional experiences of all members of the doctoral community.

A number of communication vehicles serve a multifaceted information sharing and knowledge development strategy. As faculty members and learners are often practitioners involved in their professional careers, the development of doctoral community requires specially targeted communication and collaboration efforts. In addition to the usual websites, newsletters, webinars and conference calls, it is also important to extend beyond knowledge transmission to incorporate opportunities for interactivity. For example, we created an online doctoral scholarly network that facilitates collaboration and communication between faculty, staff and doctoral learners; through this learner-driven, scholarly community, members of the doctoral community have a forum for ongoing interaction outside the confines of a single course.

As highlighted previously, the overarching goals of the doctoral vision are practice (i.e., the application of this knowledge through contributions to the workplace and society), leadership (i.e., the ability to create methods to exert positive influence in organizations and communities), and scholarship (i.e., the creation and dissemination of new knowledge). While it is important to ensure opportunities for growth along all three of these dimensions, the reality for working professionals is that they often have existing career opportunities to advance leadership and practice. In contrast, engaging in the larger scholarly community may be more challenging.

To address this disparity, learning organizations must incorporate deliberate programming to foster scholarly engagement (research dissemination through conference presentations and publishing) for doctoral learners. Through a variety of specific efforts (including workshops, webinars, informative materials, funding opportunities, etc) we endeavor to provide comprehensive support to our learners, faculty, and alumni to complete and disseminate their research. Specifically, we provide information and assistance such as up-to-date listings of conferences, avenues for engaging in discourse about research, and opportunities to engage in collaborative research. Our purpose is to enhance the position of learners, faculty, and alumni as stewards of their disciplines through participation in the both scholarly and professional conferences. As examples, we host an internal research conference for doctoral learners, publish a peer-reviewed scholarly journal highlighting interdisciplinary research at our university and participate in a university-wide research colloquium. Additionally, the university offers a grant program to financial support doctoral learners presenting their research at state, national or international conferences.

Understanding the unique needs and educational objectives of a scholar-practitioner model shifts concerns about online doctoral education from an emphasis on mode of delivery to an awareness of how the mode of delivery aligns with the broader learning model. The issue is not online or face-to-face, but rather rests in alignment of the theoretical model with the development of the curriculum and academic support structures. This type of generative learning (Senge, 1990) fosters the ability to see and understand the systems that guide the culture and events of organizational life. Effective scholar-practitioner programs involve reiterative processes that direct both individual and organizational learning and development. Learners, faculty, directors and associates engage and experience a dynamic where personal goals are strategically aligned with professional and organizational goals. The goal is to continually develop and enhance all people in the organization to support learners meeting the objectives of their doctoral programs. Through this cyclical process, the program creates the conditions for learners' success and satisfaction, always with the central goal of forming scholars, practitioners, and leaders.