Figure 1. Linking to a Book

Information literacy is defined as a “set of skills needed to find, retrieve, analyze, and use information” [3] (ACRL, 2011). Similarly, the “Big6®” consists of (i) defining the task, (ii) defining strategies for seeking information, (iii) locating and accessing information, (iv) knowing how to use the information found, (v) knowing how to synthesize the information found, and (vi) knowing how to evaluate the information found [6] (Eisenberg, 2012). Regardless of whether we are talking about information literacy or the “Big6”, there are commonalities in what is being done and taught.

Why should K-16 students, instructors, and researchers spend time navigating to find the library catalog or the databases they need to search? Why not provide direct resource links so more time can be spent finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the actual information? To address these questions, online tutorials explaining how to use persistent links to databases, journals, books, book lists, journal lists, subject lists, and Internet resources were created. This article will address how these tutorials can be used to i) Connect library resources within web pages and Learning Management Systems to support classroom instruction, and ii) Explain how the research process can also be expedited in global and collaborative workspaces [5] (Bothma, Bothma, & Cronjé, 2008).

When students are asked to complete a research project or assignment there is the expectation they will know where and how to find the information needed. The same is true for faculty who need to perform research in order to meet tenure and promotion obligations. It is assumed that students are information literate because they are technologically savvy (2009 On the Horizon, p. 4). However, the two are not the same. Likewise, it is assumed that faculty members are also information literate because they once conducted research while completing their graduate programs that required a master's thesis or doctoral dissertation. This may not be true either [4] (Badke, 2009).

So what does it really mean to be information literate? The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) defines information literacy as having “a set of skills to help find, retrieve, analyze, and use information” (2011). Similarly, [7] Eisenberg (2012) identified the “Big6®” which consists of (i) defining the task, (ii) defining strategies for seeking information, (iii) locating and accessing information, (iv) knowing how to use the information found, (v) knowing how to synthesize the information found, and (vi) knowing how to evaluate the information found.

Over the years, the research process [16] (USG BOR, 2012) has evolved due to changes in the methods and tools used for identifying, finding, and using information. At times, students and faculty may not be sure if they can or should use the Internet. Furthermore, teachers have failed to recognize how students can communicate and access information across the Internet [2] (Arafeh, S., Levin, D., Rainie, L., & (Lenhart, A., 2002) . Subsequently, the time it takes to conduct research and do a good job as well as finding information quickly seems to be concerns for any researcher[12] (Hauser, 2003; Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd 2004) , . Whenever students and faculty are uncertain of where to begin they tend to seek assistance from librarians who can help them. Regardless of whether it is the “Big6®” or information literacy, students and faculty conducting research should feel comfortable in knowing how to perform the research process in order to complete their research project or assignment.

While assisting students locate articles from reading lists provided by their professors for a variety of class assignments, several librarians found the information to be out of date, mistyped, or our library did not own it. During this time, the author was also teaching a graduate level Education course where the author required his/her students to write a research paper. Her colleagues and she/he determined it would be easier for all of her students if had a way to connect to the resources needed for their assignments and research paper. We felt this would reduce the time it took to find the articles and allow the students more time for synthesizing and analyzing the information they found. Moreover, faculty and students expected smooth access to the information they were seeking [13] (Hoffman, 2001). So we asked ourselves how could we do this [9](Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004); [14](Shepherd, Skinner, & Fernekes, 2007) . Instead of students and faculty needing to know which database(s) to select and search then look for the article(s), we found linking technologies could help us. Reference linking services or citation linking also known as linking technologies can be defined as persistent Internet links used to connect directly to online articles, books, or other information resources [11] (Ell, P.J., 2002; Grogg & Ferguson, 2004) .

The linking technologies can be used by the faculty and librarians to create assignments and conduct research making it easier to access and promote the use of information in an effort to improve information literacy [9] (Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004). Initially, the colleagues and the author identified and used six tools to connect resources through web pages and online learning management systems. The Electronic Journals A-Z list allowed us to connect directly to specific journal titles. If journal titles in a specific subject area were desired, they could connect to those as well. Next, the used the library catalog to connect to specific books and/or journal titles. Similarly, to the Electronics A-Z list, the library catalog could also be used to identify lists of books and/or journals arranged by subject and links could be made available to these lists. Another way they linked to information was to connect to specific databases or databases grouped by subject. This same method also allowed us to link directly to specific articles found in those databases. And lastly, resources placed on course reserves could also be linked to from within a course management system or web page. ([9] Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004; [14] Shepherd, Skinner, & Fernekes, 2007 , [17](Zach S. Henderson Library, 2012). Other resources may be linked as well (e.g., web resources found using Google Scholar, RSS feeds, and video and audio clips).

In an effort to explain how faculty and librarians could use the linking technologies, my colleagues and I created workshops as K-16 professional development opportunities. Participants received hands-on training on how to create and add links to their webpages or learning management system. Additionally, tutorials with detailed instructions and graphics were created using PowerPoint for those not able to attend a professional development workshop. These tutorials described the purpose for each tool, told how to create a link using the tool as well as provided examples of how the tools could be used. All this information was compiled into one location online for easy access [17](Zach S. Henderson Library, 2012). Furthermore, if any faculty member creating links had difficulty, they were given the name and contact information of the librarian assigned to their department or college so they could seek assistance or ask for demonstrations. Ultimately, the author was able to expand and tailor the professional development workshops for the College of Education faculty at my home institution, and teachers and media specialists in the K-12 system.

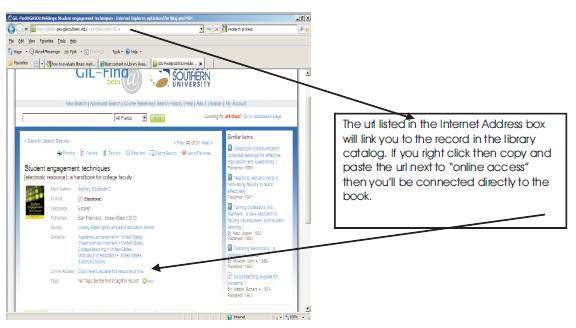

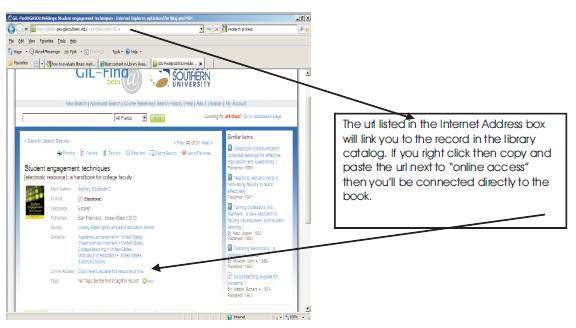

So you ask how can these tools be used in your class? Let's say you have assigned the following book, Student Engagement Techniques, to your class (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Linking to a Book

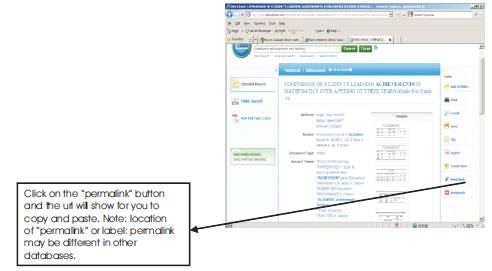

Some of your students have expressed their concern about not being to purchase the book so you want to know if it is available in the library for them to use. You search for the book title using the library catalog and determine the library owns an electronic copy. Once you have found the record for the book then you look for the persistent url. The link may be identified as “online access” if it is an online book like this one. After finding the link, you will copy the link then paste it into the course management system as a bookmark or in a web page [17](Zach S. Henderson Library, 2012) . Students unable to purchase the book will now be able to access the information without any problems. Another example may involve finding a journal article on student achievement and mathematics over a three year timeframe for an upcoming discussion group. As long as you have some part or all of the bibliographic citation (e.g, author's name, journal title, article title, date, page numbers, volume/issue number), the article can be located (Figure 2). Once located, the persistent link should be available which can also be copied and pasted in the same manner as the persistent url for the book [17] (Zach S. Henderson Library, 2012)

Figure 2 Linking to a Journal Article

In the same way a faculty member made resources available to students in their classes, these same resources can be made available to colleagues working on research projects, or students collaborating on group projects.

Using the linking tools helps us to spend more time analyzing and using the information as described in the “Big6®” as opposed to spending time finding the information [10] (Forbes, 2004) (Table 1).

Table 1.Comparison of Information Literacy and the Big6 and How It Relates to the Research Process.

More meaningful, high interest reading material is made available for instructional and research purposes [10] (Forbes, 2004, p. 149). This also ensures that the appropriate information is being accessed and used as well as decreases dependence upon nonscholarly search engines and frustration trying to find information ([6] Eisenberg, 2003; [9] (Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004) . Connecting directly to the information also allows us to share more resources by linking to them from a web site or course management system instead of filling up our email inboxes with excessive attachments that might take up lots of disk space on our computers. Additionally, this reduces the chance of losing printed copies of or finding inaccurate information. Furthermore, those who are collaborating on projects do not have to be in the same location or time zone when working because these linked resources are accessible online from any location and are made available any time ([5](Bothma, Bothma, & Cronjé, 2008) . This allows for more global and collaborative workspaces. The only caveat is making sure those who are accessing these resources from remote locations are able to do so using proper credentials because of usage restrictions placed on information accessible via proxy servers, firewalls, digital object identifiers, or similar mechanisms ([13] Hoffman, 2001; [9] Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004. Summarily, linking technologies can help students and faculty build collaborative relationships, incorporate resources into their educational activities, abide by fair use and copyright laws, access more reliable resources, and promote and publicize more opportunities for utilizing library funded resources.

Creating global and collaborative workspaces is becoming more and more prevalent. If you are interested in making such an environment for your class or research group consider incorporating linking technologies. This will allow you to connect directly to books, articles, subject lists for books or journals, databases, or course reserves while providing easy access to your students and colleagues. Using these linking technologies to connect directly to library resources should help to promote information literacy and serve the students better in locating information as described by the “Big6®” [10](Forbes, 2004); [9] (Fernekes, Skinner, & Shepherd, 2004). This also ensures students will be using library funded materials instead of less reliable resources found on the Internet [15](Trainor & Price,2010). And the faculty is better able to work more collaboratively regardless of location. If you would like more information or other relevant resources about the linking technologies tutorials feel free to visit my Google sitehttps:// sites.google.com/a/georgiasouthern.edu/shepher d-gugm-2011-resources/.