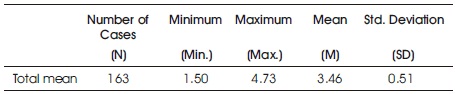

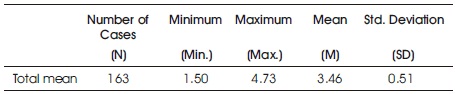

Table 1. Overall Mean Score of the Students' Learner Autonomy

The present study investigated learner autonomy level and the use of language learning strategies in a sample of 163 firstyear English majors in university. The aim of the study was to find out the correlation between language learning strategies and autonomous learning. The data collection instruments included a self-rating questionnaire and an open-ended interview. Results indicated the participants were moderately autonomous learners and their overall frequency of strategy use was medium with the most frequent use of memory and social strategies and the least of compensation and Affective strategies. Pearson correlation indicated that there was a positive correlation between learner autonomy and overall language learning strategy as well as across the six strategy categories. Understanding the relationship between learners' strategy use and autonomy may enable EFL instructors to incorporate language learning strategy training in teaching to ultimately improve learners' English language skills.

Over the last few years, there has been a significant change in the language teaching, leading to less emphasis on teachers and teaching, but greater stress on learners and learning, which can be observed in the shift of teaching methodology from teacher-centered to learner-centered. The teacher-centered methodology was and is still favoured. This teaching method emphasizes the teacher's role and neglects the importance of the learner himself in the classroom, and focus mainly on how to teach learners knowledge. Due to this traditional teaching method, students are completely passive in their study.

However, things have changed over time. The teaching methodology is now moving towards the learner-centered orientation, with which learners play a significant role in the process of learning. Learners are no longer passive in their learning process; instead, they are an active role, generating ideas and availing themselves of learning opportunities, rather than simply reacting to various stimuli of the teacher (Knowles, 1975). They are expected to involve actively in learning activities as well as to learn independently. Teachers, therefore, are not in the role of a knowledge purveyor, but a facilitator to instruct and guide their learners how to learn well. In other words, in today's foreign language classroom, learners take more responsibility of their own learning and teachers help learners become more independent both inside and outside the classroom. As a consequence of this, learner autonomy has emerged in the field of language education (Benson, 2001).

Language learner autonomy is defined as the ability to take charge of one's own learning (Holec, 1981). However, student's own learning should not be understood as teachers and peers' complete independence (Benson, 2001; Little, 1991; Littlewood, 1999).

Leaner autonomy has been regarded as the ultimate purpose of the learning process, especially if education aims to develop life-long learners. Since an independent learner becomes output product of education, cultivating learner autonomy should be the primary pursuit of teachers and educators (Mcdevitt, 1997, p. 34, cited in Naizhao, 2006). For this reason, many researchers and educators believe that developing learner autonomy is essential to become effective language users (Littlewood, 1996; Nunan, 1996). However, the concept of leaner autonomy historically originated from Western countries and was part of the Western culture, leaner autonomy may be alien for learners from different cultures in Asia, where there exist significantly different approaches to teaching and learning (Gremmo & Riely, 1995). One of the assumptions associated with learner autonomy is that it is a Western education trend unsuitable to Eastern contexts, which have traditional methods of teaching (Chan, 2001). It is often assumed that such pedagogical approach in the East would be problematic to foster the development of leaner autonomy in Asian cultures (Chan, 2003; Lamb, 2004).

The empirical result from the study by Trinh (2005) evidenced that the paradigm of using to learn and to learn how to learn the language in the curricula could stimulate learner autonomy and communicative competence. Moreover, this paradigm benefited the learners whose initial level of self-regulation and autonomous learning's attitudes were not high.

From the studies of independent learner in Asian contexts, it is obvious that learners are innately un-autonomous, but it might be the educational systems that have not created sufficient opportunities for students to be autonomous. Therefore, the Asian education systems should provide more room for students' involvement in their language learning process. It is noticed that the results from key research on autonomous learning in Asian backgrounds raise a need to reconcile the idea whether learner autonomy should be seen having the West's cultural values and the Asian traditions of teaching and learning are inappropriate” (Jones, 1995, p. 6, cited in Littlewood, 1999). Instead, learner autonomy can be viewed as a concept which accommodates different interpretations and is appropriate for everyone, rather than based solely on Western values, liberal values” (Sinclair, 2000, p. 13). As Aoki and Smith (1999, p. 3) concern, the important issue is whether autonomy itself is appropriate or not, but how the negotiation of autonomy versions can be best enabled in all contexts, in varying ways, in educative counterbalance to more authoritarian, teacher-dominated arrangements. In other words, learner autonomy is biased not only to Western values, but can also be stimulated in non-Western contexts.

As it was the case of learner autonomy, strategies in language learning has been a major concern among the scholars. In fact, the term “language learning strategies” is defined in many ways by many key researchers in the field. Having a wide range of definitions, the concept “language learning strategy” is somewhat fuzzy. According to Tarone (1983, p. 67), language learning strategy is broadly defined as the linguistic and sociolinguistic competence in the target language have made an attempt to develop. Later, Rubin's (1987, p. 23) Learning strategies contribute to the development of the evolving language system directly. While Rubin (1987) views strategies of language learning as those to develop learners' language competence in linguistic aspect and Tarone (1983) sees mastering new linguistic and sociolinguistic information about the target language are learners' attempts, O'Malley and Chamot (1990, p. 1) define individuals use the special thoughts or behaviors to help them comprehend, learn, or retain new information”. Also, Cohen (1998, p. 4) offers that learners select those processes are consciously and may result in action taken to enhance the learning or use of a second or foreign language, through storage, recall and application of information about the language. Concurring with those definitions that learning strategies are specific actions, behaviors, thoughts learners use to progress their learning. According to Oxford (1990, p. 8), the learner takes specific actions to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations. From her viewpoint, learning strategies are not only an important tool for active, self-directed learning, but also for personal enjoyment. As a result, learning strategies for second language learning are learners use specific actions, behaviors, or techniques to make learning more meaningfully, effectively, enjoyably, and independently (Oxford, 1990). Moreover, learning strategies help learners to manage and control their learning to achieve their desired goals (Rubin, 1987).

Learning strategies are believed to play a vital role in language learning since language learning strategies not only facilitate learning, but also accelerate it. As Rubin (1987) maintained, the extent to which learners succeed in their learning depends too much on the degree of strategies learners employ. In fact, researches have shown that language learning strategies use significantly correlates with language achievements (Green & Oxford, 1995; Liu, 2004; Ok, 2003).

The roles of language learning strategy in autonomous language practice have also been acknowledged by several researchers (e.g., Chamot, 1999; Oxford, 1990; Rubin, 1987; Wenden, 1991) since not only do they help encourage learners to enter autonomous language learning practice, but they also serve as tools for learners to learn by their own. As claimed by Oxford (1990), language learning strategies are important tools for active and selfdirected involvement in language learning enable learners to engage in the target language more effectively and independently from teachers, thus, become more autonomous learners who are responsible and taking control over their own learning. Similarly, White (1995) exerts that in order to practice autonomy, the learner needs understanding the nature of language learning as well as of his/her role in that process, and as part of this the knowledge of language learning strategies. Also, Cohen (1998, p. 67) supports that students' efforts to reach language program goals is enhanced by the strategy instruction, which encourages students to find their own pathways to success, and thus it promotes learner autonomy and self-direction”. Chamot (1999) further points out that strategy instruction helps learners consciously control what should they learn to become efficient, motivated, and independent language learners. When learners engage in language learning strategy use, they can understand their own learning processes and exert some control over these processes; therefore, they take more responsibility for their own learning. This knowledge about self-regulated learning helps them to be successful learners.

Although research in this area was still in its infancy, the present study made an attempt to venture into this relatively unmapped territory. It is hoped that the current study will inspire the nature of learner autonomy and language learning strategy use, thus, contributes to the promotion of autonomous learning, especially in the university teaching context in Viet Nam. This study aims to identify to what extent first-year English-major students perceived themselves as learners autonomy and what types of language learning strategy they employed to assist their learning. It was an attempt to investigate the relationship between autonomy and the language learning strategy use in a Vietnamese context. Specifically, the following three objectives were addressed:

In this study, 163 students (from five classes of English-major freshmen) were randomly chosen from a population of approximately 200 students whose proficiency level was pre-intermediate of a university in Viet nam. Their age ranges from 17 to 20. The study was carried out at the beginning of the last semester of the academic year 2016- 2017, from March 2017 to June 2017.

4.2.1 Questionnaire for the Participants

Autonomous learning and language learning strategy use are, for the most part, unobservable (Chamot, 1999). Therefore, the only way to investigate learners' autonomy and language learning strategy use is to rely on the means of self-reports, which are predominantly quantitative in nature and depend mainly on questionnaires to draw out learner's viewpoints. There are two sections on designing questionnaire to collect data.

The first section is Learner Autonomy, a five point Likert scales self-reporting questionnaire measuring learner autonomy. On the basis of existing elements of learner autonomy proposed by Trinh and Rijlaarsdam (2003) and from learner autonomy questionnaires of other researchers, especially Camilleri (1999). A twenty-two item questionnaire with three main clusters (1) Metacognitive and Cognitive consists of items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 18, 20, (2) Affective consists of items 10, 12, 19, 21, 22, (3) Social consists of items 9, 14, 15, 16, 17.

The second section is 36 short statements, each describing the use of a strategy. These items were adapted from the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) designed by Oxford (1990). (1) Memory-related consists of items 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 19, (2) Cognitive consists of items 8, 10, 20, 23, 33, 34, (3) Compensation 11, 12, 13, 14, 22, 24, (4) Metacognitive consists of items 1, 2, 3, 15, 26, 35, (5) Affective consists of items 16, 17, 18, 30, 31, 36, (5) Social consists of items 21, 25, 27, 28, 29, 32. Each item includes a statement about learners' autonomy and language learning strategy use followed by five-point scales (Never true or almost never true, Usually not true, Somewhat true, Usually true, Almost or almost always true). The questionnaire was designed in detail in English and Vietnamese to help students understand all of the items clearly.

4.2.2 Interviews

The interview consists of questions concerning learners' autonomous learning activities and the strategy categories the subjects reported using in the questionnaire to confirm the reliability of what the students reported on the questionnaire as well as gain an overview of the relationship between autonomy and learning strategies.

The data was collected by the researcher. One-hundred sixty-three copies were administered to 163 first-year English-major students. They were asked to answer each statement by rating the extent to which you agree or disagree on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “never true of me or almost never true” to 5 “always true or almost always true”. The students felt free to choose either the English or the Vietnamese version of the questionnaire. In addition, the researcher attended there to explain any statements or words they did not understand. They were allowed to spend as much time as they needed to complete the questionnaire. On average, students completed the surveys within 30 minutes.

Two weeks after the questionnaires were distributed, 12 participating students who had the highest, medium and the lowest means on the self-report questionnaire were invited for an interview. To make it easier and more comfortable for students to respond to the questions during the interview, they felt free to choose to speak either English or Vietnamese to fit their desires.

The software SPSS for Microsoft Windows was used in statistical methods. The one sample t-test, the paired samples t-test, and the pearson correlation test were utilized to reveal whether there was any significant relationship between learner autonomy and the language learning strategies.

As suggested by the literature, metacognitive, cognitive, affective, and social capabilities all underlie learner autonomy (Trinh & Rijlaarsdam, 2003). This section, therefore, reports the findings on the overall learner autonomy as well as aspects of autonomous learning.

The one sample t-test was conducted on the participants' scores to evaluate whether the mean was significantly different from 4, the accepted mean for high level of autonomy. The results are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Overall Mean Score of the Students' Learner Autonomy

The sample mean (M = 3.46, SD = 0.51) was significantly different from 4.0 (t = -13.443, df = 162, p = 0.00). This means that the participants' autonomy was above average. The results support the conclusion that the participants' autonomy level was lower than that of the accepted mean for high level of autonomy M = 4.0 on the scale of “1 as minimum” to “5 as maximum”; however, this value (M = 3.46) was above average, which implies that the level of learner autonomy by the students was moderately high.

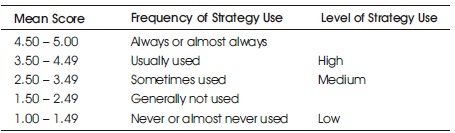

In order to measure how frequently the students employed language learning strategies, the researcher utilized the criteria created by Oxford (1990). According to Oxford, the frequency of strategy use includes three levels based on the mean scores: low (M = 1.00 – 2.49), medium (M = 2.50 – 3.49), and high (M = 3.50 – 5.00). Oxford's (1990) criteria in assessing the frequency of language learning strategy use were illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Criteria in Assessing the Frequency of Strategy Use (Oxford, 1990, p. 300)

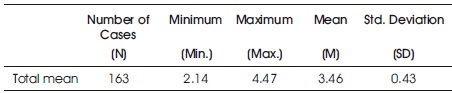

As can be seen in Table 3, the total mean score of the participants' strategy use (M = 3.46) was above average in the scale of “1 as minimum” to “5 as maximum”. The sample mean M = 3.46 (SD = 0.43) was significantly different from 4.0, the accepted mean for high level of strategy use (t = -15.95, df = 162, p = 0.00). The results support the conclusion that the participants' level of strategy use was lower than that of the accepted mean. The data analysis of the questionnaire showed that the participants were strategic learners. Their awareness of language learning strategy use was higher than that of the medium level. This means that the participants' strategy use was above average.

Table 3. Overall Mean Score of the Students' Strategy Use

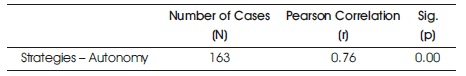

In order to investigate whether there was a statistically significant correlation between the learner autonomy and the language learning strategy preferences of the students, the Pearson correlation was performed. The statistical test was run at level of 0.00 and the Pearson r value is 0.76, which denotes a strong positive correlation between learner autonomy and learning strategy use (N = 163, r = 0.76, p = 0.00). This result indicates that there was a co-operaitive relationship between the use of learning strategies and autonomous learning. That is, the more the participants used language learning strategies to assist their learning, the more autonomous they would be in their learning and vice versa. The results of are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Correlation between Autonomous Learning and Learning Strategy Use

The findings from the interviews on learner autonomy revealed that the majority of interviewees agreed on the efficacy of autonomy in effective learning. It should also be noted that most participants demonstrated their willingness to engage in self-directed learning activities such as taking charge of their learning through analyzing their own strengths, weaknesses, or language needs, determining learning objectives, defining the content and progression, selecting methods and techniques to be used, monitoring the procedures of acquisition, and measuring their own progress. Nonetheless, a few of them showed their less confidence in involving in self-directed learning and seemed to be uncertain about their own abilities to identify their own strengths, weaknesses as well as evaluate their own progress.

The relationship between language learning strategy use and learner autonomy was examined through the pearson correlation test. The results indicated a positive significant relationship between learner autonomy and strategy use. Moreover, all six categories of language learning strategies were statistically significant correlated with learner autonomy.

This research pointed out that the language learning strategy use among first-year English-major students was at average level, among which Memory and Social strategies were most frequently employed while Affective and Compensation strategies were the least used. In addition, the study findings demonstrated a significant correlation between autonomous learning and language learning strategy use in the learning process. Thus, it is suggested that the strategy factor was taken into consideration in promoting learner autonomy.

At present, life-long learning has been regarded as an ultimate goal in language education. However, autonomous learning capacity is not an inborn, but an acquired and developed capacity (Dickinson, 1995), it seems essential for educators to equip learners with tools for undertaking their learning so they can learn independently.

The strategy of learning language has been acknowledged as effective tools helping learners to learn a language more effective, transferable, self-directed, and enjoyable through a variety of tasks. Indeed, the use of this strategy has been documented to contribute to learners to study by themselves. This study examined the relationship between autonomous learning and language learning strategy use. Such study was needed by language teachers in university context so that teachers can develop a more appropriate autonomous environment for their students. The participants were 163 first-year students at university majoring in English.

The findings showed that students possess characteristics of autonomous learners. Generally, these learners held positive attitudes towards learning autonomy. They valued the vital role of autonomy in effective learning. They agreed on the efficacy of learner autonomy, which creates opportunities for their own learning with the help of teachers as facilitators. Indeed, these learners were willing to take responsibility for their language learning process because they had the notion of responsibility in their minds, see themselves as influential factors contributing to their learning success and they generally felt themselves capable of engaging in autonomous learning. In addition, the majority of them were already, to some extent, practicing some kind of autonomous behaviors outside the classroom. It should also be worthy noting that the reason for the students not to be fully engaged in self-directed learning was that they were not confident enough in their ability to get involved in autonomous learning activities.

In addition, EFL (English as a Foreign Language) students at university applied the whole spectrum of language learning strategies to assist their English language learning. However, their application of strategies was just at medium range. Among the six categories of language learning strategies, the participants tended to use those which could help them memorize the target language items easily and effectively (Memory strategies) and learn with others (Social strategies). In the meantime, the students seemed not to find it helpful using compensation and affective strategies in their learning; they reported that they seldom use these because they were not used to applying such strategies.

Moreover, a positively significant correlation was found between learner autonomy and language learning strategies. Besides, there was a connection of all six categories of language learning strategies – memory, cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, affective, and social strategies among these participants with Metacognitive strategies, which gained the strongest correlation with learner autonomy. According to Oxford in 1990, taking steps in planning, monitoring and controlling over their own learning in order to be involved in autonomous language learning were essential for learners. Therefore, the more the participants used Metacognitive strategies to regulate their learning, the more autonomous they would be in their learning and vice versa.

Implications for Autonomy

From the results of this study, two important classroom implications were drawn. Firstly, students seem to have positive view about their abilities to learn autonomously. Therefore, English teachers should encourage their learners to become involved in the language learning process.

Teachers may use more autonomy-encouraging activities with their learners. Being aware of the activities that students are engaging in, teachers may try to create conditions to facilitate the use of these activities in order to encourage learner autonomy.

To fulfill the goal of enhancing students' autonomy, and their learning success as well, teachers should take strategy training into account. They can do that right in their classrooms, as Oxford (1990) confirmed, unlike most other characteristics of the learner, such as aptitude, motivation, personality, and general cognitive styles, learning strategies are teachable. This idea is also supported by Ok (2003); the researcher stated teachers can help their students learn more quickly, more easily, and more effectively by incorporating learning strategy instructions into language classrooms.

First of all, the participants were English-major freshmen at university; therefore, the results might not be generalized to other populations whose learning backgrounds are different. Therefore, more research should be conducted with different characteristics, such as students of different mastery levels, students from non-English majors, as well as upper secondary school students to have a global picture of the relationship between learner autonomy and language learning strategy.

Secondly, this survey completely based on the self-report questionnaire which mainly relied on the individual respondent's perceptions. Thus, it is likely that learners will not remember the learning strategies they employ or they might claim to employ strategies that in fact they do not use or there might exist a discrepancy between their autonomy perceptions and their actual autonomous behaviors, which might affect the validity and reliability of the research. As a result, further research should be conducted with other instruments (besides questionnaires and interviews) such as observations and tests to avoid this limitation.