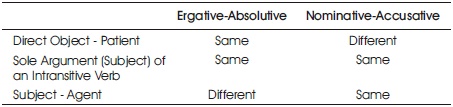

Table 1. The Comparison between Nominative-Accusative and Ergative-Absolutive Language Systems

Considering the controversy about the nature of ergativity, the issue of whether a case morpheme is theta assigning or just structural case-marking, the present study tried to provide an evidence for either side or both. To this aim, the acquisition and use of ergative verbs were studied and possible explications of the errors were presented. According to the results, ergativity is not just a structural case, but a non-structural case marking. Besides, the uninterpretable features or feature trace can account for case errors and present potential explications for the agreement failure. Based on the principles and stages of the Contrastive Linguistics Hypothesis and Error Analysis, the results of the current study can be applicable for the practice of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL). After the linguistic description and explanation of the errors made by the Persian speakers, learning English as a foreign language, the TEFL practitioners can make use of the findings of the present study to see the points of difficulty and more focus on them.

The study of grammar as the skeleton of a language like the English language in both process and product of acquisition and production has always been one of the main concerns of the researchers and practitioners of the Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and English Language Teaching (ELT). For example, Samanta (2017) investigated 'the attitudes of teachers towards teaching English grammar as Second Language (L2) and their Effects on Instructional Practices in West Bengal'; Singaravelu (2008) studies 'the effectiveness of Video Game based Learning in English Grammar at standard VI'; Ramesh and Sumathi (2010) 'developed and standardized a CAI package using Macromedia Flash 8 software for learning English Grammar—Voice for Eighth standard students'; and Singaravelu (2014) researched 'the impact of Gadget based Learning of English Grammar at standard II'. However, the present study is an attempt to delve into a specialized field of English linguistics, i.e. syntax, and investigate the technical issues of the acquisition of ergativity by the Persian-Speaking Learners of English.

One potential challenge for learning and using ergativity comes from the ergative case marking system because of the discrepancy between the ergative system in morphology and the accusative system in syntax. L1 (first language) learners of English as an ergative language should learn one system, nominative-accusative, for both syntax and morphology, but it might not be the case for L2ers. In the dichotomy of ergative-absolutive, some languages fall in either one like Persian (Karimi, 2012) and English, which are both ergative and Basque, which is absolutive. Some languages are purely and some others are split ergative. For instance, the Australian language Dyirbal is split-ergative. It is ergative morphosyntactically in all contexts except when a first or second person pronoun appears. Tense, aspect, case marking, and agentivity of the intransitive subjects are the other conditions, which cause split-ergativity.

According to Dixon (1994), the Indo-Iranian family for example, behave partially ergative between the perfective and imperfective aspect. A verb in the perfective aspect makes its argument(s) be marked in the ergative pattern, while the imperfective aspect causes accusative marking. There are also some languages, which always tend to show ergativity in past tense and/or perfect aspect.

The other binary alignment to languages is the nominativeaccusative case marking which is, like ergative-absolutive, a morphosyntactic realization that can be manifested by morphology, visible coding features, and/or syntax, through their behavior in participation of specific constructions. In the nominative–accusative alignment, the subject of transitive and intransitive verbs are distinguished from the objects of transitive verbs through word order, case marking, and/or verb agreement. Then nominative–accusative languages contrast with ergative–absolutive languages, in that in the latter, the coding of the subjects of transitive verbs differs from subjects of intransitive verbs and the objects of transitive verbs, while in the former the same coding system is used for the subject of both transitive and intransitive verbs, but a different coding system is applied for the direct objects of transitive verbs (van Valin, 2001). Table 1 illustrates the comparison between the two in terms of arguments.

Table 1. The Comparison between Nominative-Accusative and Ergative-Absolutive Language Systems

Moreover, unaccusative verbs contrast with unergative verbs. An unaccusative verb is an intransitive verb whose argument is not an agent; that is, it is not actively responsible for the action of the verb. An unaccusative verb's subject is semantically similar to the direct object of a transitive verb, and to the subject of a verb in the passive voice. For instance, while resign and run are in the category of unergative verbs, fall and die are included in the unaccusative verb category because although the subject has the semantic role of a patient, it is not assigned as the accusative case.

Among outstanding studies on the importance areas of the acquisition of the ergative verbs which pose problems for their learners, Zobl (1989); Ingham (1996); Can (2009); Ju (2000) can be mentioned. The investigation of ergativity and ergative verbs is so multifold that there are considerable critical issues raised by leading scholars. For example, Yip (1994) poses the problem of rejecting the correct NP-VP (Noun Phrase - Verb Phrase) order of the ergative verb of shatter by the learners. Furthermore, Can (2009) maintains that

"Four studies (Abdullayeva (1993), Montrul (1997) Karacaer (1998) and Can (1999)) on acquisition of ergatives by Turkish Learners of English show that Turkish learners of English avoid ergative structures and mostly prefer passive structures instead. Abdulleyava's (1993) analysis has demonstrated that the rate of avoidance increases as the proficiency level increases. Kellerman's (1978) and Karacaer's (1998) findings supports the case" (p. 2).

Having explained the cardinal terms and grounds with which the current study is concerned, the identified syntactic issue is the case checking of the nominative and accusative case features of pronouns placed in the agent and patient argument positions with ergative verbs.

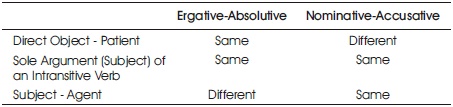

In the minimalist framework of Chomsky (2000, 2001) and related works, case and agreement are so interconnected that are viewed as two of the same, i.e. both are morphological products of phi feature checking process of a syntactic application, called Agre*. Figure 1 illustrates how the case marking and feature checking of an agreement is mutually applied.

Figure 1. A Tree Diagram of Inter-Association of Case and Agre Feature Checking

The nominative features of agents are specified by the tense phrase. An NP is an agent (subject) enjoying a nominative case when it is the first constituent, which is c-commanded by the head of a TP (Tense Phrase). In other words, the interpretable phi features of T are checked by the firs c-commanded NP constituent and it, in return, gives an agent/subject-argument position. Similarly, the trade-off of feature checking and case marking between V and the first NP constituent c-commanded by it, makes the NP a patient (object) and as a result the agreement emerges. However, in some languages like Amharic it is a V which agrees with both the subject and object. In a study, Baker (2012) investigated the object agreement and accusative case in Amharic and argues that accusative case and object agreement are not the manifestations of the same abstract relation in Amharic. That is, it is possible to have morphological markings and object agreement with DPs, the accusative DPs that the verb does not agree with. While in English, where case marking and agreement are applied rather syntactically than morphologically, there needs to be two conditions for the trade-off of case marking and agreement: being the first NP node c-commanded by the head V or T and the quality of the verb and head T bearing active nominative or accusative features needed to be checked by that node. So the NP and the head need each other one way or the other in order for the head whose features be checked by the NP and grants the NP a case. Thus, one of the distinctions between transitive and intransitive verbs lies in their head V features. Now when transitivity and intransitivity is a feature quality of verbs, how come some verbs are both transitive and intransitive, called ergative? Would it (feature checking- not-checking) be the reason why Persian native, low proficient, non-native speakers of English make errors using personal pronouns using transitive and intransitive states of the ergative verbs?

They are transitive head V´s that yield the accusative case to patients once they check the accusative features of the V´s. What happens when some verbs are both transitive and intransitive?

Holmberg and Odden (2004) present a similar argument to ergativity in a study in German and then Howrami and proposed that ergative transitive verbs give unaccusative case features to the object NP. In other words, the transitive ergative verb has the quality of giving unaccusative case features (too). On the other hand, head T has the nominative features to be checked by the subject NP. Then the obj NP moves to spec of T by the Extended Projection Principle to check the features of the T and leaves a copy trace constructing an argument chain. Reversely, the subject NP has the unnominative features as well given by the verb, which are not active with intransitive verbs.

Thus, a hypothetical answer to the above question might be the defective intervention in the agreement of T and object NP. That is the NP in object position, moves to the spec of VP and the spec of T leaves a non-spelled-out defective trace in its first trip, which creates uninterpretable features and a crash to the subject-verb agreement in its second trip.

In another view, the phenomenon can be argued through Chomsky´s (1986) inherent case argumentation. An inherent case is a case, which is dependent on thetamarking (as opposed to the structural case). Also, a case is called inherent if its assignment is an idiosyncratic property of the assigning head.

Case-marking would have to be determined, even partly, and be active before spelling-out in the narrow syntax. Woolford (2006) also states that

"In addition to the division in Case Theory between structural and non-structural Case, the theory must distinguish two kinds of non-structural Case: lexical Case and inherent Case. Lexical Case is idiosyncratic Case, lexically selected and licensed by certain lexical heads (certain verbs and prepositions). Inherent Case is more regular, associated with particular theta positions: inherent dative Case with DP goals, and ergative Case with external arguments" (p.1).

If languages can parametrically vary on whether they connect the syntactic case to the morphological case or not, then it is impossible to claim that they are two sides of the same feature complex. But the standard inherent case story depends on the notion that inherent case assignment is in fact the special assignment of morphological case that gets in the way of the subject raising. So they are related to some extent.

As discussed above, subjects in non-ergative verbs receive their case from the head T, while the ergative case, which is an inherent case is given by the head v of two-place ergative verbs and also depends on theta marking (Woolford, 2006; Legate, 2008).

In the meantime, McFadden (2003) argues that using the inherent case theory as an explanation for why an object cannot become a subject is potentially circular. He argues that

"That is, it is improper to posit inherent Case-assignment solely on the basis of subject ineligibility and then to use this same inherent Case-assignment to explain the subject ineligibility. It would of course be possible to avoid this circularity if the special inherent Case mechanism were independently necessary to get the morphology to come out right, which is the basic idea of the standard account. The way it is supposed to work is that the case that shows up on certain DPs is morphologically exceptional, thus it is plausible to assume that it is assigned by an exceptional mechanism. Then, since it is just these DPs that cannot become subjects, it is plausible to assume that this exceptional mechanism of case-assignment takes place in the syntax and is what blocks raising to subject" (p.153).

Considering the huge bulk of researches and investigations on ergativity in different languages linguistically and cross-linguistically, such as Yeon (2008), Coon (2012), Aldridge (2012), and Mahajan (2012); and the leading significance of ergativity in the foreign language acquisition, as Bavin and Stoll (2013) state "Ergativity is one of the main challenges both for linguistic and acquisition theories". The present study attempted to pin point the errors and problems of Persian EFL learners and account for them for a more effective path in the practice of English Language Teaching (ELT).

For the purpose of this study, one intact group from an English institute in Isfahan, including 30 female participants, were selected, to control the gender variability. The participants' age ranged from 20 to 35. They were all Iranian students of differing majors studying English as a foreign language at lower-elementary level. The language proficiency level of students was determined according to CEF (Common European Framework). CEF is a guideline used to describe the achievements of learners of foreign languages. It is a system of validation of language ability with six reference levels: A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. The elementary level equals A2, where learners can understand sentences and the frequently used expressions related to the areas of most immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal and family information, shopping, local geography, employment). They can communicate in the simple and routine tasks, requiring a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar and routine matters. They can also describe, in simple terms, the aspects of their background, immediate environment, and the matters in the areas of the immediate need.

The participants for the interview test were selected through the purposive method. They were the learners who were selected randomly for being taught personal pronouns through using ergative verbs in a course.

In the present study, the objective personal pronouns were taught to one group of 30 female Persian native speakers learning English as a foreign language at the lower elementary level, to make sure that the errors were not caused by the ignorance of the objective pronouns. Then, they were asked to make sentences with some ergative verbs, once with nouns and once with pronouns; once in the transitive state and once in the intransitive state of the verbs.

Accordingly, in a quasi-experimental design, the subjects of the experimental group were taught subject and object pronouns using ergative verbs for giving examples by the teacher along with oral and written practice during the term, studying the book 'Total English' by Mark Foley and Diane Hall in order that the researcher makes sure they know objects and objective pronouns. Moreover, they were provided with passive voice in another lesson in term syllabus. Then, at the end of the term they were given some cards with some cartoons and ergative verbs at the elementary level, such as destroy, burn, change, close, fly, etc. They were asked to make sentences with each provided verb, using the visual clues in an oral assessment in the form of an interview. They should make one sentence in the transitive state with N's, one in the transitive state of the same verb with equivalent Pronouns, one in the intransitive state with N's, one in the intransitive state of the same verb with equivalent Pron.'s The students were explained that they would be given a card with some pictures and verbs to make four sentences with each, related to the picture, before the interview time. So the examiners, firstly, called students and as warm-up asked them to start with introducing and talking about themselves, their family and educational background, interests, hobbies, and the like. Then, the examiners, who were not the researchers, gave the subjects the card with required direction. In order not to disturb the examinee or make her stressed, while she was making sentences the examiner just jotted down just the faulty sentences. The interviews were implemented in two separate rooms by two examiners at the same time. There were made 15 different cards as instruments, containing 4 verbs. The response time to students was not tight. Later reliability was not an issue to be taken into consideration because the interviewers just objectively wrote down the exact sentences of the subjects and their subjective idea, criterion, or evaluation was now involved in the process of data gathering.

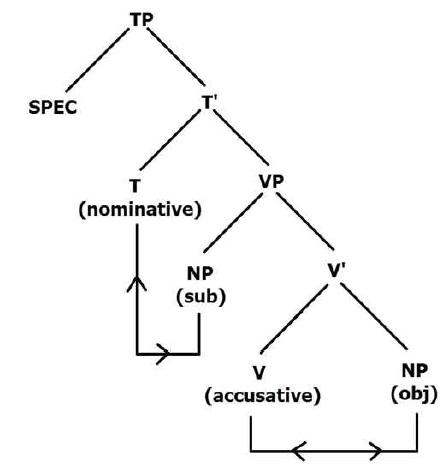

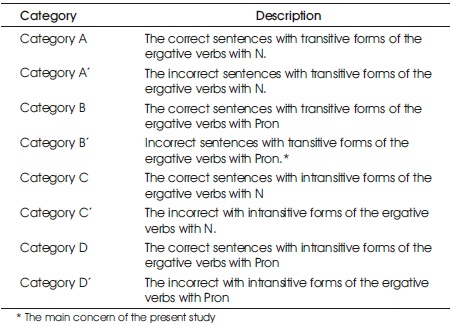

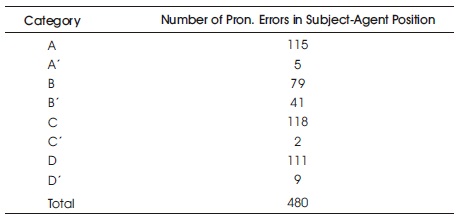

The scoring of the subjects' answers to the question of making two sentences for each of the four verbs in per card is in four categories. Table 2 illustrates the categorizing method of the scoring technique.

Table 2. The Categorization of Verb Forms with their Descriptions

As it has been displayed in Table 3, the large number of correct answers to classes C and D show that students know the agre features of number, gender, person between subject and verbs and can identify the equivalent subject pronouns of relevant N. Moreover, the odd number of incorrect answers, or less than 4, indicates that they might have occurred by mistake. The large number of Class A shows that subjects know the place and function of objects and subjects and the incorrect answers are not from one participant. From the total incorrect answers in A´, B´, C´, and D´, which is 57.71% is from Class B´, (which is the main concern of the current paper). The incorrect answers in category B´ reveal that students had case problem. They could not identify and shift the object pronoun to subject pronoun.

Table 3. The Results of the Interview

The term ergativity has been one of the most common systems used in all languages. Accordingly, its acquisition, learning and use, have been as one of the most frequently investigated phenomena. The current study was an attempt to investigate the inherent nature of ergative case acquisition. The results indicated that the issue is not just a structural assignment as Marantz's (1991) generalization and his followers like Legate (2008, 2012) claim. It has been postulated that ergative case never appears in derived subjects. Derived subjects, including non-thematic ones, may agree on the ergative pattern as shown in Bruening´s (2007) study in Passamaquoddy. Given the findings of the interview test, and the primary objective of the study, which is accounting for and penetrating into agre errors of ergative verbs from different perspectives, one explication for B´ is the degree of UG availability. When UG is available for L2 learners as well as L1 users, and the default case for L1 acquirers is the checked object pronouns (accusative), the results indicated that UG is available for L2 learners with its default case. The incorrect answers would be more likely the effect of UG availability than L1 transfer because the subjects´ L1 and L2 are ergative languages. So UG is not available via L1. It is there by itself, advocating the full-access theory to UG (White, 1985; Lardiere, 1998), yet may be just in production, but not recognition as well (regarding the Interpretability Hypothesis of Tsimpli and Roussou, 1991). In other words, B´ is against the uninterpretable features (regarding the Failed Features Hypothesis (FFH), Hawkins 1998), which is a modern version of no parameter resetting. The FFH proposes the full transfer of L1 in the L2 initial stage. It predicts the non-availability in L2 acquisition of parameterized properties not instantiated in L1. In other words, the FFH rejects the possibility of UG restructuring in L2 development. Specifically, according to Hawkins (1998, 2000), a subset of uninterpretable features will “fail” (i.e. non-acquirable and thus absent) permanently (Leung, 2003). Moreover, the error in B´ could be because of delearning phenomenon, i.e. the subjects know case and agre features in L1, but delearn it in L2, ignorance to the case features, though they know what they are, not to functional categories. Furthermore, under-specification model, which is along with continuity model, can explain B´ with underspecified features of case for L2 learners when shifting and moving subject pronouns to object pronouns (nominative to accusative) at the low level of proficiency as the initial stage in L1 acquisition. Besides, as all NPs have to take a one and only one theta role, predicate-argument structure, in the A chain of nominative to accusative, there are some uninterpretable or underspecified features, which impede the proper use of C(Category)- selection even by S(Semantic)-selection.

Category B is a support for Continuity Theory, which argues that young L1 learners start with a TP. Children following the agre features and case marking constraints of Subject- Verb is an evidence of syntactic development of language in L1 learners from TP. Additionally, in- line with the research results about UG availability with its default form to L2ers, the same or similar process or direction must be true for L2 learners, starting from the TP, in accordance with continuity building theory.

Furthermore, this stance is against Fundamental Difference Hypothesis (FDH) (Bley-Vroman, 1988), which posits that the acquisition process of children and adults is fundamentally different because children possess the innate ability to acquire the L1 grammar, whereas adults have lost this ability. While it supports Fundamental Similarity Hypothesis (Robinson, 1997).

Bley-Vroman (1988) declares that whereas children are able to acquire a language through almost completely implicit mechanisms, without reflecting on the language structure, adults, however, losing the ability of second language learning implicitly and have to, therefore, make use of other capabilities such as problem-solving ability and native language knowledge. On the other hand, Reber (1993) affirms that “implicit learning is the default mode for the acquisition of complex information about the environment” (p. 25). His result tends to prove that adults would be better at implicitly acquiring complex rules without consciously attempting to learn about these rules. Robinson's (1997) Fundamental Similarity Hypothesis confirms Reber's (1993) view that there is no evidence for dissociating between implicit and explicit learning systems in adult second language acquisition” (Thouësny, 2014).

Regarding communication as the end goal of learning a second language, it needs a unit of language as a psycholinguistic and discourse tool, called a sentence. Clark, Paul, and Rosal (1998) asserts that “[the language] it is the principal medium of human communication” (p. 41). Crystal (1987) also states that “to communicate our ideas” is considered as “the most widely recognized function of language” (p. 10). Where sentence is the keystone of this principal medium of communication, verbs are the core of this keystone, in turn. In support of this idea, Dixon (1992) states that “verb is the centre of the sentence” (p. 9). In addition, it is verbs that match the semantic (meaning) and syntactic (structure) roles and positions of the other constituents of a sentence such as case and arguments. So based on the linguistic and communicative significance of verbs, teaching verbs has the foremost importance in this profession.

The syntactic study of the acquisition of ergative verbs by Persian learners of English, will reveal results, which can account for the origin of the L2ers' errors on ergative verbs. Accordingly, based on Whitman's (1970) theory about the steps of the Contrastive Linguistic Hypothesis which is prediction, language teaching practitioners can be more focused on the points of difficulty from the learners and allocate more time and strategies in their teaching plans.

It can also be recommended that the relationship between the difficulties of the acquisition and production of the ergative verbs and other values of the independent variables such as the learners' first language and language proficiency would be studied. Moreover, studies on proposing a rating and ranking list of the ergative verbs, according to the difficulties in the acquisition and teaching of ergative verbs for second language learners with different first language are strongly suggested.

Regarding the research questions and the relevant discussion, it is now more likely to acknowledge the inherent nature of ergative case acquisition in the learning process and speech production to be more than merely a structural marking mechanism. It is both structural and non-structural (thematic) and when it fails in Persian EFL learners of lower proficiency, the remaining features of the chain argument movement of object to subject position may have caused effective intervention for agreement of head T and object (accusative rather than nominative case features).

The phenomenon of failure in agreement of ergative case is an evidence for UG availability when both standard L1 and L2 are of the similar if not similar kind. The result of the observation of the study revealed that Persian native speakers learning English at lower levels used the default pronoun in a nominative subject position, which was accusative object pronouns while they knew and were taught object pronouns in the course of the study. Thus, one interpretation is that whether UG is fully or partially available it is available with its default properties so as for L1 acquirer.

As the current study was an investigation to give account for some aspects of ergativity, pertinent errors and some (morpho) syntactic explanations of the causes of them; and on the hand the relevant implications of the phenomenon to UG availability, further studies can go deeper and shed light on the path of the explicating the indications of principles and parameters of UG via the canal of ergativity cross-linguistically.