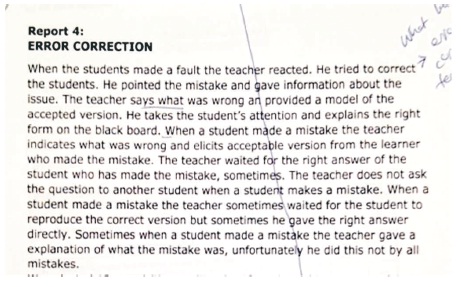

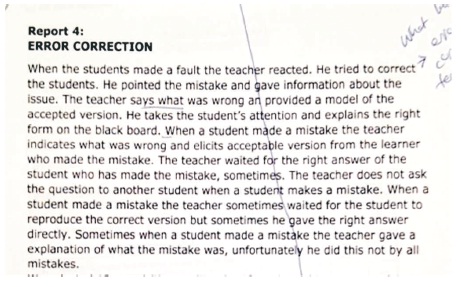

Figure 1. A Student's Commentaries on Teachers' Error Correction Practices

Recently, there has been some redesigning in the English language teaching curriculum in Turkey as a consequence of overall educational reforms. However, there has, so far, been no research that has investigated the current high school English curriculum in light of the recent linguistic developments in the field of English language teaching. Thus, the current study explores the high school English curriculum to determine whether there is any reference to the current status of English as a lingua franca in general and its implications for teaching in particular. The data consisting of curricular documents and observation reports on teachers' practises were analysed through a combination of qualitative content analysis and negative analysis. The curricular data analyses show that there is a limited mention of ELF and in name only, with almost no reference to ELF principles for teaching. Similarly, the analyses of observational data indicate that teachers follow a traditional way of teaching English without paying much attention to the current status of English and how they should prepare students for real-world English use. Overall, the results suggest that there is little space for ELF in the current curriculum at the level of policy and nearly none at the level of practice.

This research study is concerned with the question of whether there is any, overt or covert, reference to English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) and its tenets in the recent High School English Curriculum (HSEC) implemented in Turkish high schools. Part of the aim is to explore whether curriculum writers have taken well-attested findings in the field of ELF into consideration while renewing the curriculum and if so, to what extent ELF principles have informed the new curriculum at the level of policy and practice.

Investigation of curricular documents is of paramount importance considering their being among the primary type of documents in which one can find decisions about language education policy and practice. Additionally, these documents provide extensive direction on how teaching and learning practices should be like. Within them, one can also assemble factual and material information on several curricular matters and policy elements, e.g. teaching methods, study materials, classroom activities, assessment, and target interlocutors (Gray, Scott, & Mehisto, 2018). Actually, curricula should play a relevant role in introducing innovations in language teaching practices. This is why they need to be updated in accordance with the major trends and developments in the field.

Since this paper specifically deals with the curriculum and the likely existence of ELF-related principles in it, the author first introduces the status quo of English Language Teaching (ELT) in Turkish education system and the recent changes made in the curriculum in the following section.

English has become an important element of public schooling in Turkey for many decades as the principal foreign language taught and learned (Büyükkantarcıoğlu, 2004). The educational reforms spearheaded by the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) led to the changes in ELT policies and practices, as well. Although English was initially introduced as a required school subject beginning in the 6th grade, English had, between the years of 1997 and 2013, been offered to students starting from the 4th grade onward with the advent of the 1997 education reform (Arikan, 2017; Kırkgöz, 2009). To be precise, “the Turkish Government implemented a drastic change in the ELT curriculum and lowered the age of FLL to nine-ten years of age (4th grade)” (Gürsoy, Korkmaz, & Damar, 2013, p. 60). However, with the 2012 education reform, the compulsory term of education was extended from eight to 12 years divided across three tiers, widely known as the 4+4+4 education system in Turkey. Within this system, students now nd start learning English in the 2nd grade (MoNE, Board of Education, 2013). This three-tier model consists of primary, secondary, and high school components, with each corresponding to four years of instruction. At present, students start learning English when they are around seven years old in the primary school and the weekly teaching hours for English increase as students move up to the next tier.

The recent changes in the curriculum are concerned with diverse issues, including a growth in the length of language teaching, acknowledgement of the current status and role of English in the world, adoption of new approaches to teaching and testing English as well as development of innovative materials and course packs. As maintained by the MoNE (2012), it is aimed through these changes to give more space to language education and to start teaching English as early as possible, as well as to issue new regulations that will suit students' linguistic needs, personal interests, and capabilities.

These curricular changes have sparked researchers' interest in research into program/curriculum evaluation. For example, researchers investigated the 4th and 5th grade language teaching program (Topkaya & Küçük, 2010). There were also studies concerned with teachers' perspectives about foreign language teaching within the new 4+4+4 education system (Gürsoy et al., 2013). Additionally, research has been done on language teachers' views about a grade-specific curriculum, i.e. the English language curriculum for 2nd graders, implemented in Turkish primary schools (e.g. Arikan, 2017). However, to the best knowledge of the author of this paper, so far, there has been no attempt to explore the current high school English curriculum from an ELF perspective, despite previous attempts in the area of pre-service language teacher education and materials development (Bayyurt & Sifakis, 2015; Deniz, Özkan, & Bayyurt, 2016). Having identified the research gap, the author would now like to turn the ELF phenomenon and its implications for language pedagogy.

One recent development in the field of ELT is the case of ELF which deals with the widespread diffusion of the English language and its divergent use as a contact language - as opposed to idealised standards - by speakers, especially by those who do not speak English as their first language (Jenkins, 2015a, p. 73; Seidlhofer, 2011, p. 7). ELF can be said to have emerged as a reaction to the English as a foreign language (EFL) paradigm according to which target interlocutors are Native English Speakers (NESs) and the ideal model for Non-native English Speakers (NNESs) is set as native English (Jenkins, 2006; Jenkins, Cogo, & Dewey, 2011).

However, ELF researchers argue against the ownership of English by NESs, stressing that the native English model should not be imposed on language learners and users as the sole unquestioned point of reference (Jenkins et al., 2011; Seidlhofer, 2011; Widdowson, 1994). This also explains why ELF scholars consider language assessment frameworks, like the Common European Framework of References (CEFR) which “corresponds to native-like proficiency in the respective language” inappropriate in the assessment of speakers' proficiency (Jenkins & Leung, 2013, p. 1608; Jenkins, 2016). They also have similar argument on CEFR. From an ELF perspective, what is more relevant in interaction and assessment than the native-like proficiency and grammatical correctness is achieving communicative effectiveness through mutual intelligibility and getting across the intended messages, and applying various intercultural communication strategies (Björkman, 2011; Jenkins, 2016).

The target competence for ELF speakers differs from traditional conceptions of communicative competence based on “ the native speaker-based notion of communicative competence” (Alptekin, 2002, p. 57). As this understanding of communicative competence draws on standardized native speaker norms, this model is perceived as “utopian, unrealistic, and constraining,” and conflicts with the current status of English as a global lingua franca (Alptekin, 2002, p. 58). ELF supports the model of intercultural communicative competence with which speakers can efficiently communicative with people, be they NESs or NNESs, in diverse situations and contexts “with an awareness of difference, and with strategies for coping with such difference” (Alptekin, 2002, p. 63). This model seems to be more fitting for ELF interactions as it moves from a “'non-essentialist' view of culture and language that better accounts for the fluid and dynamic relationship between them” (Baker, 2011, p. 1).

As mentioned earlier, curriculum documents are among the primary existing policy documents. As the investigation of curriculum documents is a relevant matter of language policy research, this research is mapped on the theoretical framework of critical language policy.

One can see from the previous literature that language policy has been conceptualised from diverse perspectives. One of them is that of Ball (1993, p. 10) who conceptualized the term as “text”. This text is composed of “an authoritative statement (either verbal or written) of what should be done” (Bonacina-Pugh, 2012, p. 215). Similarly, Spolsky (2004) defines language policy “as an officially mandated set of rules for language use and form” (p. 3). However, some researchers argued against this traditional understanding of the term, claiming that there are other factors apart from a text that can affect language users' choices and practices.

Another perspective posits that language policy is “policy as discourse” which fits with the idea that various ideologies and beliefs underlie people's choice acts (Ball, 1993, p. 10). In Spolsky's (2004) words, this perspective deals with “what people think should be done” about language use, form, and education (p. 14). Recently, the language policy research has indicated a trend towards addressing speakers' actual language practices as well as policy texts and discourses. Therefore, from a critical language policy viewpoint, language policy is viewed as “the combination of official decisions and prevailing public practices related to language education and use” (McGroarty, 1997, p. 67). This perspective recognizes the fact that there might be discrepancies between the avowed rules and ground realities. That is, not all language policy prescriptions can translate into actual practices in the way they are stated in the documents.

Besides studying the three components of the language policy framework mentioned above, it is vital to consider the fact that “[t]he policy is embodied and realised through a series of mechanisms or structural arrangements” (Gray, Scott, & Mehisto, 2018, p. 50). Bearing in mind such policy elements, Shohamy (2006, p. 32) developed the “expanded view of LP”, arguing that “LP is interpreted not through declared and official documents but is derived through different mechanisms used implicitly and covertly to create de facto language policies” (Shohamy, 2006, p. 57). She enumerates some of these mechanisms as “rules and regulations, language educational policies, language tests, language in the public space as well as ideologies, myths, propaganda, and coercion” (Shohamy, 2006, p. 56). Therefore, regardless of what policy documents researchers are intent on analysing, it is worthwhile to take account of these policy mechanisms to determine the de facto language policies.

This study adopts a descriptive case study research design, using the English curriculum implemented in Turkish high schools as a case. Such a study “is focused and detailed, in which propositions and questions about a phenomenon are carefully scrutinized and articulated at the outset” (Tobin, 2010 p. 288). It is a well-recognized method in the field of language policy, especially when researchers seek “in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in real-life settings,” such as the appraisal of subject-matter curricula (Crowe et al., 2011, p. 1).

The policy material to be analysed in this study is the MoNE HSEC (MoNE, 2018) implemented in high schools in Turkey. The curriculum (MONE, 2018) is publicly available as a portable document format file. It has been designed for students in the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades. It is 69 pages in total and divided into two parts, the first of which addresses issues regarding the philosophy and general objectives of the curriculum, targeted competence and skill areas, ethics and values education, assessment and evaluation, and includes a guide for the curriculum, and finally introduces the organization of the curriculum. The second part presents a syllabus for each grade, with detailed accounts of how to teach English. English and Turkish are used in different sections of the curriculum separately. The first 20 pages are entirely in English while the remainder consists of a preamble for each syllabus in Turkish, followed by the syllabus of each grade in English.

Aside from the curricular data, observational data were collected. Observation reports of 12 teacher candidates observing in-service teachers in three high schools in the province of Burdur, Turkey, were included in the data set in order to address the practice dimension of language policy framework. Students were given weekly tasks and each week, they focused on a different aspect of teachers' practices, e.g. classroom management, error correction, feedback, lesson planning, and so forth. While completing weekly tasks, students used semi-structured observation guides and provided open-ended commentaries in response to predetermined task-related questions (Dörnyei, 2003; Mackey & Gass, 2005; Marshall & Rossman, 1994).

To analyse the data, the strategies of qualitative content analysis (Schreier, 2012) and negative analysis (Pauwels, 2012) were used. The major reason for choosing qualitative content analysis is that it serves “as a passport to listening to the words of the text, and understanding better the perspective(s) of the producer of these words” (Berg, 2001, p. 242). That is, the focus is placed more on the latent content, i.e. “the deep structural meaning conveyed by the message” (Berg, 2001, p. 242) than the manifest content, i.e. the content that concretely appears in the textual material(s) (Dörnyei, 2007; Krippendorf, 2012). To supplement the content analysis, negative analysis was done, because it largely deals with "meaningfully absent" elements in the materials (Pauwels, 2012, p. 253). In a language policy study, what is intentionally left unstated in the documents is as important as what is explicitly stated since meaningfully absent policy items may be symptomatic of widely held assumptions of the policy makers. Also, such implicit assumptions may be at odds with the stated policy prescriptions.

Two particular issues surfaced while analysing the HSEC. The first was about the absence/presence of any reference to the present status of English (i.e. ELF status) and the second was about the non/existence of any mention of ELF principles. The objective was to discover whether there is an orientation to a specific kind of English and particular speaker model(s), and how good/effective English is branded in the curriculum.

3.1.1 Description of the Present-day Status of English

Concerning the first issue, it was found that the curriculum writers seemed to recognize the current face of English as the major lingua franca and an international language. Below is a blurb from the curriculum that recognizes the global status of English.

There are several interdependent language teaching th th and language principles reoccurring in the 9 -12 Grades English Curriculum. First of all, English is seen as a lingua franca and international language used in today's global world” (MoNE, 2018, p. 5; emphasis in original).

The emphasis placed on the phrases, 'a lingua franca' and 'international language', may be the reason that the former curriculum did not view English as such. However, this nominal reference to ELF in the curriculum does not mean that it actually takes into account the implications of how such a global language should be taught and learned.

To ensure whether the curriculum refers to ELF principles, a closer inspection was done in the curriculum, which identified a partial mention of some ELF principles and the ideas of some English as an International Language (EIL) scholars. To illustrate some of these principles, let us look at what the curriculum (MoNE, 2018, p. 5) writes on these issues.

[a]s travel has become more common in the last decade, different cultures are in constant contact and use of English as an international language “involves crossing borders literally and figuratively” (McKay, 2002, p. 81) … [i]n order to share their ideas and culture with other people from different cultures and countries, our learners need to use English actively, productively, and communicatively.

The descriptions of the landscape of English use by culturally and linguistically different groups of speakers in the above extracts offer persuasive evidence that these descriptions resonate with the ways ELF has been defined. From the manifest content, it also appears that linguistic and cultural diversity is celebrated in the curriculum as is done in the ELF paradigm, with a particular emphasis on the role of English as a contact language. It can be infered from the above curricular extracts that English is no more seen as a foreign language primarily learned and taught to communicative with NESs in English as a Native Language (ENL) contexts.

3.1.2 (Non)-Recognition of ELF Principles related to Language Teaching

There is no explicit statement in the curriculum as to whether a particular kind of English is overtly favoured over the others. Hence, as suggested by Gray et al. (2018) and Shohamy (2006), an analysis of policy mechanisms was done. A systematic inquiry took place on the testing framework, an important aspect of assessment, against which learners' mastery of skills is judged. From this inquiry, it emerged that the curriculum adopts the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) as it can be seen in the following extracts:

This curriculum has been designed in accordance with the descriptive and pedagogical principals of The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). (MoNE, 2018, p. 4; emphasis in original)

…learners are expected to graduate from high school with a minimum CEFR B2+ and/or beyond level of English language proficiency… (MoNE, 2018, p. 7)

The adoption of the CEFR in the curriculum implies that there is indeed a hidden reference to Standard Native English (StNE) and that NESs are pointed as the presupposed target model for learners. This conclusion sounds fair when earlier criticisms of the CEFR were taken into consideration. Let us take, for example, the criticism levelled at it by Jenkins (2016, p. 10), who contends that

In all cases [the CEFR] is oriented to the native speaker version of the language … it does not distinguish between a language used mostly as a foreign language (e.g. Japanese, Korean, Polish) and a language used mostly as a lingua franca….

There is plenty of evidence in the CEFR descriptions that lend support to Jenkins' (2016) criticism. For example, the following statements in the CEFR clearly indicate the tendency towards the native speaker model with respect to speaking and listening skills.

B2 Speaker: Can interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible without strain for either party (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 24)

C2 Listener: I have no difficulty in understanding any kind of spoken language, whether live or broadcast, even when delivered at fast native speed, provided I have some time to get familiar with the accent (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 27).

Another policy mechanism examined closer was the teaching approach advocated in the teaching of English. Regarding this matter, the curriculum presents the following information:

The new 9th -12th Grades English Curriculum was designed to take all aspects of communicative competence into consideration in English classes by addressing functions and four skills of language in an integrated way and focusing on “How” and “Why?” in language rather than merely on “What?” (MoNE, 2018, p. 5; emphasis in original).

As can be understood from the above statements, the curriculum seems to support a communicative approach to language teaching in which interaction seems to be not only the means but also the ultimate goal of language teaching. To see whether the understanding of communicative competence is that of traditional understanding or aligns with the one espoused by ELF, i.e. intercultural communicative competence, a further analysis was done within the document. This analysis identified references to early theorizers of communicative approach, such as Hymes (1972) and Canale and Swain (1980), whose understanding of communicative competence was illustrative of a traditional EFL approach where native speaker competence is set as the ultimate goal. In relation to the notion of communicative competence, bearing in mind the developments English has undergone for over 40 years or so, Leung (2005, p. 120), however, argues that

the concept of communicative competence, which has provided the intellectual anchor for the various versions of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) that appear in a vast array of ELT teacher training and teaching materials, is itself in need of examination and possibly recasting.

The final policy mechanism inspected closely was the materials and technology pack and technology use. The inspection showed that there is an overt link between using authentic English and being NESs. Furthermore, exposure to authentic English is equated with taking part in communication with NESs. Such accounts incontestably reflect the ideology of native-speakerism (Holliday, 2006) and how it plays an influential role underpinning curriculum writers' beliefs. Below are some policy statements from the curriculum that illustrate the implicit connection between 'authentic use of English' and the state of being 'native speakers of English'.

Video conferencing done with native speakers can also increase the confidence and improved motivation among language learners (MoNE, 2018, p. 15; author’s emphasis)

Links to websites, blogs, and virtual environments to expose learners to authentic use of English and real communication with native speakers of English can also be added to the Tech Pack. (MoNE, 2018, p. 18; author’s emphasis)

The above statements regarding the potential use of technological tools in teaching English are in stark contradiction with the previous statements in the curriculum, which recognize linguistic and cultural diversity and the use of English largely as a lingua franca. This contradiction in the curriculum may stem from the fact that on one hand, curriculum writers are aware of the current speaker profiles of English and diverse settings of English use, but on the other hand, when it comes to language teaching pedagogy, they submit themselves to the traditional EFL paradigm, with a high level of regards to NESs as target interlocutors and with no heed to the implications of how a widely diffused language, like English, should be taught in practical terms.

The purpose of the observational data analysis was to find out whether the overt statements regarding language education and use translate into the policy actors', i.e. classroom teachers, practices. Thus, students' reports were checked in terms of error correction techniques and the teaching approach adopted in classes.

3.2.1 Error Correction Strategies

The analysis of the reports about error correction revealed that teachers predominantly preferred a form-focused error correction technique rather than a meaning-focused one when teaching pronunciation, grammar and diction. Meaning-focused error correction is one key implication of ELF research whereas form-focused error correction is the rational strategy largely implemented by those adhering to the traditional EFL paradigm (Weekly, 2015). Below are verbatim commentaries provided by students regarding teachers' error correction techniques:

S3: When they do the exercises or teacher ask questions, if the answer is incorrect he gives the correct form.

S6: This week students had an exercise about tenses. they had a really simple mistakes even in tenses…When a student made a mistake, teacher corrected it and wanted the students to repeat the corrected one. He corrected some examples before saying the correct answer, asking them if it was true or false.

It becomes clear that linguistic correctness according to a particular model, most possibly StNE, is considered more important than the communication of ideas. However, such practices stand in conflict with the ELF perspective, which attributes more importance to accommodation strategies than grammatical accuracy (Cogo, 2016). The following excerpt in Figure 1 makes it much clearer that the teacher acts under the assumption that improvement in grammatical accuracy can be realized through formfocused corrective feedback, but disregards the fact that such an improvement comes at the expense of other areas, such as oral fluency and mutual comprehension.

Figure 1. A Student's Commentaries on Teachers' Error Correction Practices

Moreover, error corrections of this kind are contrary to avowed policy statements in the curriculum, which recommends teachers to “overlook students' mistakes or slips of the tongue during speaking activities and model the correct use of language instead or take notes to work on the mistakes later as a whole class without referring to students' identities (MoNE, 2018, p. 10). At first sight, this statement may seem as ELF-friendly; however, it is evident from the overall content that mistakes can be ignored on the spot, but not tolerated under any circumstances.

3.2.2 Teaching Approaches and Methods

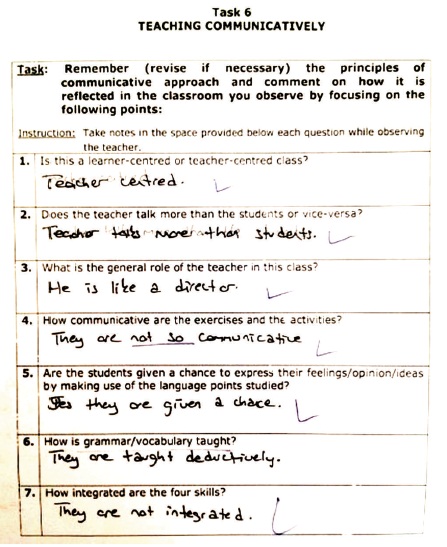

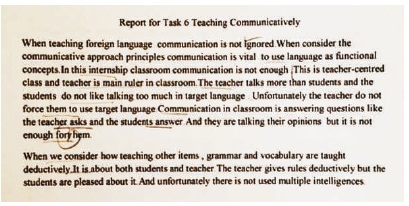

As for teaching communicatively, almost all students mentioned the absence of interactive elements in classes, underscoring that much emphasis was laid on teaching grammar and vocabulary through the medium of Turkish. Thus, it would not be wrong to maintain that classroom teaching practices were shaped by the traditional techniques of grammar-based language teaching. The following remarks and Figure 2 draw a general picture of teachers' practices relating to teaching communicatively:

Figure 2. A Student's Observations on the Teacher's Teaching Practices

S1: Actually, there was no speaking activity. There was some reading part and some writing exercises. Vocabulary is taught using grammar translation method. But grammar is taught by using L1.

S5: In fact there is no L2 usage in the classes because the lecturer is based on the GTM and teaches the language through structures.

Similarly, student reports on 'teaching communicatively', let alone teaching communicatively in accordance with ELF, demonstrated that teachers largely use elements of traditional EFL teaching methods that fail to satisfy students' linguistic needs in the contemporary situation. For instance, it can be seen from the extract in Figure 3 that it is hard for teachers to give up their traditional roles and ways of teaching.

Figure 3. A Student's Observations on the Task 'Teaching Communicatively'

This paper explored the present-day English curriculum employed in Turkish high schools through the lenses of ELF research on language teaching pedagogy. The major purpose was to see whether there are any mention and recognition of ELF and its practical implications in the curriculum. The study showed that not many significant changes occurred in the revised curriculum as to a shift towards acknowledging the plurality of English and what this means in practical terms for teaching English. ELF appeared in the curriculum nominally when describing the present-day status of English, and where it is used and who uses it mostly. This also explains why the EFL paradigm and its principles still prevail in the discourse of policy statements. Therefore, the hidden agenda comes to light as making students target native speaker competence and use English in conformity with the conventions of StNE. Observational data further corroborated the discrepancy between the stated policies in the curriculum and teachers' actual practices, which were reminiscent of traditional EFL practices.

Overall, the findings have significant implications for the understanding of how an ELF-informed curriculum should be like. In an ELF-informed curriculum, the ultimate goal is to raise students' awareness of available alternative models (e.g. successful communicator, intercultural competent speaker, skilled language user) rather than enforcing one single model (native speaker model) on students. As for an ELF-informed assessment, the focus should shift towards students' Englishing, i.e. “what they do with the language in specific situations” (Hall, 2014, p. 383). That is, the curriculum should guide teachers' attention to what students can do by using English instead of what they cannot do with English when judged against standardized forms and performance of a particular native speaker model. When it comes to teaching approaches and methods, an ELF-oriented curriculum is supposed to be based on intercultural communicative language teaching in which linguistic correctness is secondary to establishing effective communication via the application of appropriate pragmatic strategies (e.g. backchanelling, repair, signalling importance; see Björkman (2011) for more detail).

Similarly, materials and course books suggested in the curriculum should be revisited to make them more compatible with an ELF-informed language teaching. As Vettorel and Lopriore (2013, p. 485) notes, when teachers are “provided with the “appropriate” and realistic materials”, they can “go beyond an exclusive focus on English-as-a-native-language standard varieties”. It is therefore crucial to raise teachers' awareness of ELF pedagogy because even if the curriculum is made compatible with ELF, it is teachers, the key policy actors, who will act as the agents of change, and as long as they are not convinced of the utility of an ELF-informed pedagogy, any curriculum innovations will remain limited to policy papers, but will not translate into actual practices.