Figure 1. A Model of Effective Job Performance (Boyatzis, 1982)

With Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN 2015) ushering market integration, including free exchange of human resources among member countries, employer expectations from university graduates adapt to the increasingly competitive demands of the global workplace. Such development makes more urgent the alignment of academic and professional prioritization of work-related skills. Specifically, this study compares the oral communication skills deemed essential by accounting supervisors and the proficiency of entry-level accountants based on their selfassessment. To achieve this research objective, two questionnaires were prepared and administered through electronic mail-one for 100 accounting supervisors and another for 100 entry-level accountants, both randomly selected from the Big Four Audit Firms in the Philippines. Respondents rated each oral communication skill based on essentiality and proficiency, respectively. The results suggest that listening is the most essential oral communication skill in the work of new accountants. Also, entry-level accountants perceive themselves as “very proficient” in four out of five oral communication skills which accounting supervisors consider “highly essential.” The ability to “describe situations accurately and precisely to superiors” is the only highly essential skill that the entry-level accountants need to improve. Generally, the findings reflect positively on the work-readiness of the entry-level accountant respondents in relation to oral communication skills.

The dynamic nature of the business environment has led to the development of the accounting profession globally and locally. Accounting is known as a service activity that provides quantitative information, primarily financial in nature, about economic entities in order to assist in economic decision-making (Robles and Empleo, 2012). However, accountants today are expected to go beyond this delimitation of function. Businesses seek more from the accounting profession as the market evolves and technology advances. This growth in professional expectation presents a critical concern among businesses as deficiencies are noted in the skills set that accountants bring to the workplace.

A survey identified the three most important skills of an accountant, such as written communication, oral communication, and analytical or critical thinking (Sharifi, et al., 2009). Academics and practitioners concur with the said results, confirming that accounting students' writing and oral communication skills are two major areas needing more curricular attention (Gray, 2010; Jones, 2011; Rollins and Lewis, 2012). However, this pedagogical priority cannot be easily realized as the curriculum for programs of knowledge professions, such as Bachelor of Science in Accountancy, tends to be dominated by specialized technical skills (Ballantine and Larre, 2009; Jackling and De Lange, 2009; Uyar and Gungormus, 2011). Hence, it is common for educators and students to give less priority to generic skills, such as general writing, interpersonal skills, and communication. This tendency, however, proves detrimental to the success of accounting graduates to secure employment as communication skills are ranked as the top personal quality employers consider in hiring job applicants (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2001). In its newsletter keying in, the National Business Education Association validates the importance of business communication in the work of the most indemand accounting-related jobs, including financial managers, controllers, cash managers, and securities and finance service sales representatives. With these reports, it can be said that graduates' acquisition of suitably strong communication skills represent a particular and ongoing concern to accounting firms (Gray, 2010).

Paucity of related studies in the Philippine setting suggests insufficient guidance to those aiming for a career in audit as regards the specific communication skills preferred by their potential employers. This gap inspires an inquiry on whether there is convergence between the skills set sought by audit firms as employers and the accounting graduates' oral communication skills developed in their undergraduate studies. To probe the issue, this study aims to compare the essentiality of work-related oral communication skills as evaluated by supervisors in the Big Four Audit Firms in the Philippines and the proficiency of entry-level accountants in the said skills based on their self-assessment. Specifically, the study attempts to answer the following questions.

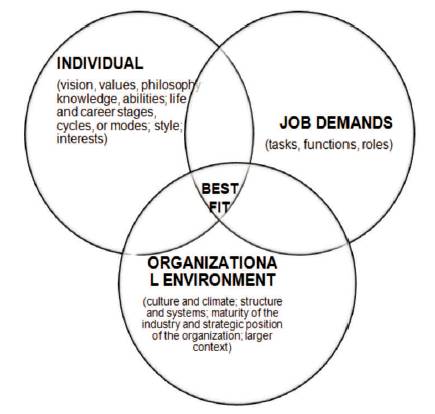

In 1982, Richard Boyatzis established the link between competency and job performance by proposing a Model of Effective Job Performance, also known as the Contingency Theory of Action and Job Performance. This framework has found valuable application in competency-based evaluation of professionals, which is of particular interest in human resource management (Yeung, 1996). It appears to be the forerunner of the succeeding work of Boyatzis focusing on behavioral manifestations of competencies, including emotional intelligence, which has been found to have an important impact on graduate management education (Boyatsiz, Stubbs, and Taylor, 2002; Boyatzis and Saatcioglu, 2008) and leadership effectiveness (Boyatzis, 2006; Boyatzis, Smith, and Blaize, 2006). As depicted in Figure 1, this model shows three components that contribute to effective action or positive performance on the job, such as organizational environment, job demands, and individual's competence. Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of these three components, whereby interaction or presence of the three results in good performance or effective action. Conversely, non-correspondence of any of the components yields ineffective behavior or action (Vathanophas and Thai-ngam, 2007).

This current research adapts the framework, focusing on two components as follows.

The researchers examine the presence of convergence or divergence between these two components. Although the study does not examine organizational environment, the findings could prove beneficial for both audit firms and accounting education providers by providing insight to augment corporate training practices and instructional content and delivery, thereby affecting organizational environment towards improved employee performance.

Figure 1. A Model of Effective Job Performance (Boyatzis, 1982)

Prior studies reveal that if employees want to be successful in the highly fluctuating global business environment, they must exhibit a range of technical and generic skills (Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Business Council of Australia, 2002; Ferguson, 2010; Michigan State University, 2011; Mitchell et al., 2010). Over two decades ago, accountants associated professional success to their technical skills, but with the release of the Bedford Committee Report (American Accounting Association, 1986), the perception that accountants should go beyond technical skills was effectively formalized, leading to conclusions that generic skills are likewise contributory to professional success (Jackling and De Lange, 2009; Johns, 2010; Jones, 2010). This paved the way for studies, such as that of Kavanagh and Drennan (2008), which identified a full range of skills needed in the accounting profession. Among the business skills deemed essential for employability are communication, problem solving, interpersonal, and organizational skills (Gammie, Gammie, and Cargill, 2002, as cited in Crawford et al., 2011). Another related study acknowledges five critical business skills based on management education literature - decision-making, analytical, leadership, interpersonal, and communication skills (Dacko, as cited in Crawford et al., 2011). It is apparent in these studies that communication is a consistent theme in the skills employers prioritize in hiring decisions. Clearly, employers expect employees to be effective communicators and rate employees for their communicative performance. However, employers reportedly perceive new graduates as lacking in this skill (Bunn et al., 2006; The Conference Board, 2009). It is little help that most related studies fail to probe into the specific communication skills that new accountants need to be competent in. Gray and Murray reported this in their 2011 study:

Studies of communication in accountancy agree broadly on the importance of written and oral communication skills. Many formal and informal studies to this point have tended to use general terms such as “communication skills” or the even vaguer term “generic skills.” It is difficult to ascertain the precise meaning of such all-encompassing terms as they apply to chartered accountancy (Gray and Murray, 2011, p. 277).

Within the body of research regarding communication skills in relation to the accounting profession, most are centered on written communication skills. Fewer studies have focused on oral communication skills. But in 2008, a study by Johnson, Schmidt, Teeter, and Henage ranked oral communication first and written communication fifth among the core skills for employment (Johnson et al., 2008). Responding to the noted significance of oral communication, Gray (2010) attempted to identify the specific oral communication skills desired from new accountancy graduates. She produced an inventory of 27 oral communication skills categorized into listening, collegial communication, client communication, communication with management, and general audience analysis. The findings revealed that the skills are valued in this order as follows.

Surprisingly, formal presentation skill, which is typically given focus in undergraduate language instruction, is reportedly considered least valuable. More alarming, however, is evidence that the oral communication skills considered significant by employers are seldom found in new graduates.

A number of studies (e.g., Anderson, 2013; Kerby and Romine, 2009; Keyton et al., 2013) have examined the importance of oral communication skills in the perception of both accountancy students and graduates. Various studies suggest that students consider the profession as one that does not require oral communication competence. Many students, both accounting and nonaccounting majors, regard accountants as merely number crunchers (Ameen et al., 2010; Maubane and Oudtshoorn, 2011). Consistent findings from different studies suggest that accounting students generally consider the profession as more dependent on technical skills than communication skills (Ameen et al., 2010). Gray and Murray (2011) have found that new accountancy graduates seldom acknowledge the value of oral communication skills in their chosen profession. Perhaps related to this perception is the finding that accounting students experience higher oral communication apprehension, an individual's level of anxiety associated with either real or anticipated oral communication, than other business majors (Bryne et al., 2009). Researchers suggest that if the perception of accountancy students on the importance of oral communication skills does not change, graduates may not be competitive enough to meet the needs in the accounting workplace. However, despite the consensus among these studies, a definitive conclusion cannot be made as Jackling and De Lange (2009) reported divergent results indicating that participating accountancy graduates in their study ranked communication skills, oral and written, as the most important quality needed to succeed in the accounting industry.

Other perception-based studies explore the self-assessment of accounting students on their level of proficiency in specific oral communication skills. Gray and Murray (2011) reported that accountancy graduates and students believe that they have “substantial deficiencies in interpersonal skills and oral expression” (p. 277). An earlier study by Gray (2010) on the issues that accountancy graduates encounter at the beginning of their career revealed that “communication with others” is a major impediment for accounting majors. Despite these identified areas of concern, oral communication continues to be taken for granted as a pedagogical target as evidenced by programs focusing more on written communication skills (Kavanagh and Drennan, 2008). Graduates confirm that there is underemphasis given to generic skills, including oral communication skills, during their undergraduate studies (Jackling and De Lange, 2009).

A critical issue arises when there is a gap between the expectation of firms and the perception of new graduates on the importance of non-technical skills (Daff et al., 2012; Jackling and De Lange, 2009; Klibi and Oussii, 2013). This, in fact, is noted in the emphasis employers give to generic skills and the new graduates' disregard of these skills (Amee et al., 2010). This variance in perception appears to arise from a lack of understanding on the part of accounting students and educators on the new skills expected from future accountants (Klibi and Oussii, 2013).

As confirmed by related literature, accounting and finance professionals who are struggling to find a job can offer their expertise in the market by developing skills that employers seek (Hagel, 2012). To achieve this goal of making graduates work-ready, the misconception that Certified Public Accountant is a profession that requires minimal oral communication skills ought to be challenged. This study is one such effort to clarify the oral communication skills necessary for accounting practice and to align priorities in education and practice. Although the results may not be conclusive for all graduates of higher education institutions providing accounting education, this research has potential contributions in curricular innovation, work placement of accounting graduates, as well as corporate training in audit firms.

A descriptive-quantitative design, specifically correlational research, is employed for this study. In contrast with qualitative research, where researchers co-formulate the meaning of the phenomena along with the participants (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009), quantitative method generates more objective, empirical outcomes sans subjective influence. A correlational research design was adopted because it identifies the characteristics of a phenomenon and provides an objective assessment of the relationship of two or more subjects (Farrelly, 2013).

The research was conducted in Metro Manila, particularly in the main office locations of the Big Four Audit Firms, namely, Sycip Gorres Velayo and Co. (SGV & Co.), Navarro Amper & Co. (NA & Co.), Isla Lipana & Co., and R.G. Manabat & Co. (RGM & Co.). These firms are partner firms of global audit service providers, such as Ernst and Young, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, Price water house Coopers, and Klynveld, Peat, Marwick, Goerdeler, respectively. They are also identified as employers of choice, who hire a significant number of accounting graduates yearly. The noted hiring trend is expected to increase steadily in the next four years (Sengupta, 2014) as ASEAN member countries prepare for economic integration in 2015.

Two sets of respondents selected from these audit firms are accounting professionals and entry-level accountants. Accounting professionals, or accountants who practice public accounting as senior employees or those occupying any supervisory position (e.g., senior associate, senior consultant, associate manager), were selected using purposive sampling. Due to the confirmatory factor on the determination of the population size of accounting professionals in the Big Four Audit Firms, a quota of 100 respondents was deemed the appropriate sample size. Similarly, purposive sampling was applied to select 100 entry-level accountants who earned their Bachelor of Science degree in Accountancy from the same topperforming accounting school (University of Santo Tomas - Alfredo M. Velayo College of Accountancy) in 2011 to 2013.

To gather data for analysis, a survey method was employed using two questionnaires: one for the accounting professionals and another for the entry-level accountants. Both questionnaires consisted of a series of short statements about oral communication skills, which the respondents were instructed to rate using a five-point Likert scale. The professionals gave ratings based on the essentiality of the skills in accounting work while the entrylevel accountants gave ratings based on their perceived level of proficiency in each skill.

With due permission, the two questionnaires were adapted from the study of Gray (2010) as the said tool appears to be the most comprehensive inventory covering the different facets of oral communication skills related to accounting practice. The foundational study of Gray was based on the tool developed by McLaren (1990) to assess the importance of written and oral communication skills to chartered accountants and the skills performance of entrylevel accountants in New Zealand. The said instrument was combined with inputs from other studies on oral communication to generate a full list of specific oral communication skills. The original questionnaire, which consisted of 27 specific oral communication skills, was modified to suit the current study. Revisions include converting the phrasal items into sentence form to facilitate comprehension by the respondents and omitting some questions, such as the General Audience Analysis Skills (maintaining composure in front of audience, holding audience's attention and interest, using the appropriate vocabulary for a specific audience, and earning respect from audience members), which are not applicable to entry-level accountants. Consequently, these changes reduced the number of oral communication skills to 17 in total. Both questionnaires were divided into two sections: the first section included demographic profile items, and the second section listed the 17 specific oral communication skills, which are grouped into:

The survey instrument for entry-level accountants was reviewed for content validity and pilot tested. Ten entrylevel accountants currently working in the Big Four Audit Firms participated in the pre-testing of the second questionnaire administered through electronic mail. The result verified acceptable validity of the entire questionnaire with each section yielding high validity percentages exceeding the 70% minimum rating: listening skills (85.9%), collegial communication skills (80.9%), client communication skills (90.4%), and communication skills with management (82.2%). The researchers deemed it unnecessary to subject the survey instrument for accounting professionals to further tests of validity, since the tool adapted from Gray (2010) was originally designed for employer-respondents.

To analyze the data, different statistical methods were used to determine and compare the most essential oral communication skills as evaluated by accounting professionals and the most proficient oral communication skills of entry-level accountants based on their selfassessment. Weighted mean and standard deviation were applied to the responses of accounting professionals and entry-level accountants. The mean scores and the interpretation describe the degree of essentiality and proficiency while the standard deviations describe the dispersion of the scores for each oral communication skill. The scores were then ranked to determine the most essential oral communication skills as evaluated by accounting professionals and the oral communication skills, which accountants are most proficient in based on their self-assessment. To further determine which among listening skills, collegial communication skills, client communication skills, and communication skills with management is the most essential, a one-way analysis of variance using the F-test was performed. This test was used to determine if multiple variances are all equal. In the study, the overall computed mean scores and standard variations of each category was compared and determined if equal. However, when the finding from the F-test reported at least one of the categories to be significantly different, a posthoc comparison test was performed. This test is used to assess which group, among the specific categories of oral communication skills relating to the study, differs from the rest. Finally, two-tailed T-test was performed on each oral communication skill to determine if significant differences exist between level of essentiality of each oral communication skill and level of proficiency in oral communication skills.

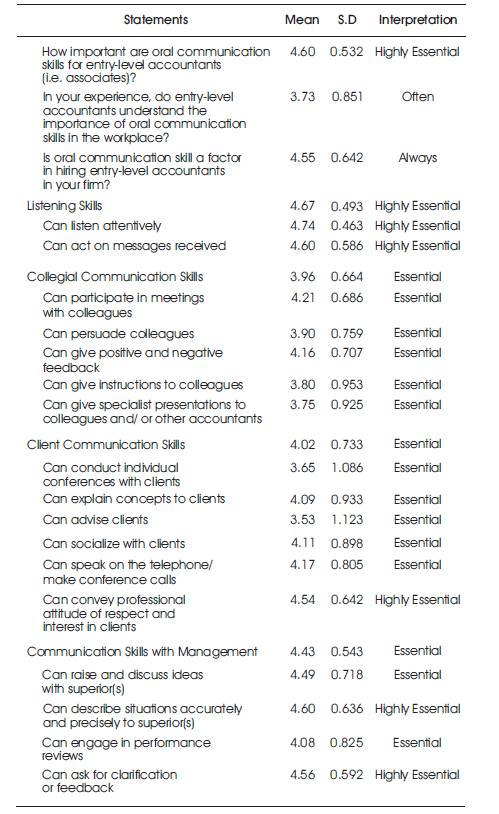

Table 1 shows the mean scores describing the degree of essentiality that accounting professional respondents ascribe to each oral communication skill. As can be seen, oral communication skills are deemed highly essential in the work of entry-level accountants and are evidently considered in hiring decisions.

In terms of the different specific skills, five were regarded as “highly essential” (with mean scores of at least 4.5), specifically: can listen attentively, can act on messages received, can convey professional attitude of respect and interest in clients, can describe situations accurately and precisely to superiors, and can ask for clarification or feedback. The other 12 skills were rated “essential”. It is important to note that no skill was considered “not essential”. This supports the assertion that oral communication, in general, is a relevant skill in the work of entry-level accountants.

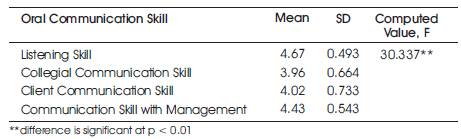

Tests were also conducted to further determine which among listening skills, collegial communication skills, client communication skills, and communication skills with the management is the most essential. A one-way analysis of variance using the F-test was performed. Since results show that atleast one of these skills is significantly different, a posthoc comparison test (Tukey test) was also done. This enabled the researchers to determine which particular skill has a significantly higher mean score than the other skills, which eventually led to the identification of the most essential skill.

Table 2 shows that the mean score for “listening skills” is highest among the four skills, and the scores given by the accounting professional respondents are the least dispersed around the mean (SD = 0.493). The next higher mean score is for “communication skills with management” (Mean = 4.43, SD = .543). Also, the computed value of the test statistic F is 30.337, with a corresponding probability value less than 0.01. These numbers suggest that at least one oral communication skill set is significantly different, necessitating a post-hoc comparison test.

Table 3 shows the results of the post-hoc comparison test. As shown, “listening skills” is significantly more essential than the three other oral communication skills, as evidenced by significant positive mean differences of 0.706 (probability value < 0.01), 0.655 (probability value < 0.01), and 0.238 (probability value < 0.05). This indicates that listening skills are the most essential oral communication skill according to accounting professionals. This is in agreement with the findings of several other studies including Gray (2010) and Gray and Murray (2011).

It is also notable that “communication skills with management” is assessed as more essential compared with “collegial communication skills” and “client communication skills”, with significant mean differences of 0.469 and 0.418 (both at probability values < 0.01), respectively. Furthermore, there is no significant difference between the essentiality of “client communication skills” and “collegiate communication skills,” as evidenced by an insignificant mean difference of 0.051.

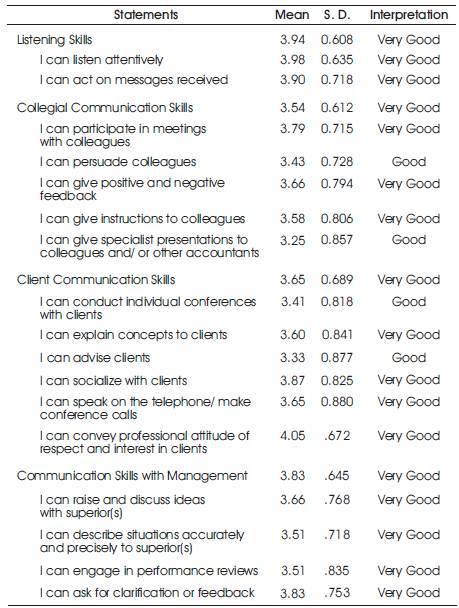

The same statistical treatments were applied to the responses of entry-level accountants to determine in which oral communication skills they are most proficient. Table 4 summarizes their self-assessments regarding their oral communication skills.

As shown, entry-level accountants perceive themselves to be “very good” in most oral communication skills. Highest mean score is observed for the ability to convey professional attitude of respect and interest in clients (Mean = 4.05, SD = 0.672). In other skills, they also claim to be “very good” in listening attentively, acting on messages received, socializing with clients, and asking for clarification or feedback. They perceive themselves to be “good” in persuading colleagues, in giving specialist presentations to colleagues and/ or other accountants, in conducting individual conferences with clients, and in advising clients.

A two-tailed T-test of differences between the essentiality and perceived proficiency was performed to compare the results gathered from the accounting professionals and from the entry-level accountants.

As shown in Table 5, there is a significant difference between the evaluated essentiality of and perceived proficiency in the following skills: persuading colleagues (t = -3.490, p-value < 0.01), giving specialist presentations to colleagues and/ or other accountants (t = -2.756, pvalue < 0.01), and describing situations accurately and precisely to superior(s) (t = -5.392, p-value < 0.01). In all three cases, the essentiality scores given by the accounting professionals are significantly higher than the selfperceived ratings of the entry-level accountants. This indicates oral communication skills where entry-level accountants may need further support in university language instruction and/ or corporate training.

From the same table, it is also evident that a significant difference exists between the essentiality of and proficiency in the following skills: giving positive and negative feedback (t = 2.180, p <0.05), socializing with clients (t = 2.317, p < 0.05), and speaking on the telephone or making conference calls (t = 2.620, p < 0.01). Entry-level accountants perceive themselves to be “very good” in the aforementioned skills, while accounting professionals regarded these as “essential.” Although these skills are not “highly essential” in the work of entry-level accountants, being highly proficient in them may reflect positively in the conduct of audit work.

The specific skills where no significant difference is noted may signify areas where entry-level accountants comply with what is considered as highly essential skills by the Big Four Audit Firms. More importantly, based on the results reported in Tables 1 and 2, three skills, namely listening attentively, acting on messages received, and conveying professional attitude of respect and interest in clients were rated high by both accountancy professionals (highly essential) and entry-level accountants (very good). This seems to indicate that new accountants are already very proficient in the oral communication skills, which the Big Four Audit Firms consider highly essential in the work of an associate.

Table 1. Essentiality of Oral Communication Skills in the Work of Entry-level Accountants (n=100)

Table 2. Test of Differences among the Essentiality of Oral Communication Skills

Table 4. Proficiency of Entry-Level Accountants

The pertinent findings of the study relative to the research questions are as follows.

Overall, the findings of the study report that all oral communication skills are deemed essential in the accounting profession. Thus, it may be concluded that oral communication is highly essential in audit practice and serves as one of the deciding factors in hiring entry-level accountants. It appears that entry-level accountants, particularly those who graduated from University of Santo Tomas, are relatively confident about their proficiency in this generic skill. However, the extent of their self-assuredness regarding their competence varies in some skills. The skills that are reported as “highly essential” but with lower perceived proficiency rating are the communication skills that can be potentially prioritized in the curriculum of accounting majors. Pedagogical response, however, is expected not only from instructors teaching communication courses to accounting majors, but also and more importantly, from educators handling technical accounting courses. The latter should communicate through example and instruction, the necessity for certified public accountants to be adept in numeracy and communication. Meanwhile, the skills which are reported to have high proficiency rating, but are regarded as not highly essential may be considered as an advantage on the part of the new accountants as these skills may still be useful in the workplace.

The reported findings provide important insight for human resource development in accounting firms. Specifically, the results may help define the content of corporate training for new accountants, targeting the specific oral communication skills that are essential to their workplace tasks. This course of action is further supported by considerable evidence of accounting students' Communication Apprehension (CA) or public speaking anxiety. Several studies report that accounting majors are more apprehensive to speak than other business students (Aly and Islam, 2003; Arquero et al., 2007; Foo and Ong, 2013). The most recent findings of Darang et al. (2015) show that final-year accounting students in a Philippine university had higher, although not statistically significant, CA scores than hotel and restaurant management majors. They also found that the CA level of accounting students was higher in formal speaking tasks, such as interviews and presentations, than in informal contexts, such as group discussions and conversations. An explanation offered by Ameen et al. (2010) refers to accounting majors' misconception on the importance of oral communication skills in their target career. A productive measure to address these pedagogical gaps is the planning and implementation of training and mentoring program, whereby the oral communication competence of entrylevel accountants is assessed upon hiring and their progress is constantly checked by their immediate supervisors. It is critical to use a reliable assessment tool to evaluate their proficiency levels at each stage of the training program to avoid reliance on self-ratings that are subject to bias issues. The performance ratings of new accountants from these training seminars may then be considered as part of competency-based evaluations for promotion decisions.

An important limitation of this study is the use of selfassessment to obtain data on the proficiency level of new accountants. Perception-based methods are known to be subject to implicit biases of the self-raters; hence, accuracy of reports is likely to be questionable. A standardized proficiency test may be employed in future research to reflect actual proficiency ratings in oral communication skills. Another critical restriction in the study is the modest sample size for both cohorts of respondents. Although the sample used was deemed acceptable, a larger number of respondents and representation from other accounting education institutions could potentially result in more conclusive findings.